You’re Free to Go,” Commanders Told Hungarian POWs—They Answered: “We’d Rather Work for You. NU

You’re Free to Go,” Commanders Told Hungarian POWs—They Answered: “We’d Rather Work for You

The Choice of Knowledge

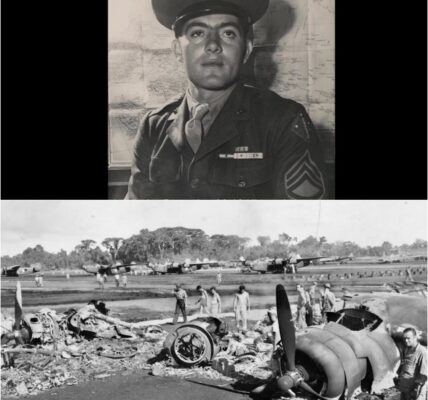

It was May 7th, 1945, and the morning sun cast long shadows across Camp Atterbury, a military base in Indiana. Captain Thomas Harrian stood before a group of Hungarian prisoners, clipboard in hand. The news of Germany’s surrender had reached this corner of the world just hours earlier. The war in Europe was over, and these men were free. At least, that was the intention.

The camp’s vast, makeshift barracks were quiet except for the soft rustle of American soldiers moving through the rows of men who had been captured in various parts of Europe. Captain Harrian, hoping for cheers or at least some visible relief, delivered the announcement through Lieutenant Michael Kovatz, the camp’s Hungarian-American interpreter.

“Gentlemen,” Harrian said, his voice firm, “the war in Europe is over. According to the Geneva Convention, and by direct order from the War Department, you are free to go.”

A silence followed. No cheers. No tears. Just a thick, uncomfortable stillness. The prisoners exchanged glances, unsure how to react to their newfound freedom. They had been told their time as prisoners would come with hardship, possibly violence—but nothing had prepared them for this moment, where the enemy, in this case, the Americans, were offering them something entirely unexpected: liberty.

Captain Harrian had overseen many groups of prisoners, but this was different. He had expected relief or joy, perhaps some sign of their long-awaited release. Instead, the response was confusion, hesitation.

A tall, thin man stepped forward. “Sir,” the man said, his accent heavy but clear. “I am Major Lazlo Fete, the senior officer of this detachment. With respect, we would like to request permission to continue working at the depot.”

Harrian blinked, unsure if he had heard him right. Kovatz translated the words, and the request seemed even stranger the second time around. “We wish to stay and work,” Major Fete continued, pointing to the other prisoners standing silently behind him.

The captain’s confusion deepened. He had seen many prisoners who had been eager to go home, to reunite with families, to escape the horrors of war. But these men were asking to stay, to continue working at an American supply depot, a facility where their captors had been processing vehicles for the war effort.

Harrian glanced at Kovatz, who looked equally puzzled, then turned back to the Hungarian major. “You want to stay?” Captain Harrian asked incredulously. “You’re free to go. Why stay?”

The answer came, not just from Major Fete, but from many of the men standing behind him. “We wish to learn,” Fete replied, “to understand how you have built this.” His voice grew more impassioned. “The system. The machines. The scale of it all. It’s… it’s not just about the abundance, but how you organize it.”

Captain Harrian stood there, dumbfounded. He had overseen hundreds of prisoners, but none had ever requested to stay. He did not yet understand that what these men had witnessed at Camp Atterbury had transformed their entire worldview. What Major Fete and his men had seen at the depot went beyond industrial capacity—it was an education in how a country, even an enemy, could marshal its resources and organize its efforts with precision and purpose. For these men, this was not just about war, but about the future.

For the men of the Hungarian military, war had always been about survival and sacrifice, about fighting for something greater than themselves—whether that was the glory of Hungary or the promises of the Third Reich. But when they arrived at Camp Atterbury, they found themselves in a place that contradicted everything they had been taught. It was not just the scale of American industrial production that shocked them; it was the system behind it—the sense of order, the quiet confidence, and the undeniable success of it all.

Major Lazlo Fete had been a motorized infantry officer before his capture. As an engineer, he had been trained to believe that European engineering—particularly Hungarian and German—was the pinnacle of technological advancement. Yet here, on this American base, he witnessed a system that defied everything he had been taught. At the motor pool, rows of identical engines from various American manufacturers—Chevrolet, Ford, Dodge—stood lined up in perfect order. It was a sight that paralyzed him.

“We were told that American vehicles were unreliable, that their engines would fail under pressure,” Fete recalled years later in his memoir. “But here, everything was uniform, interchangeable. No one had told us that such consistency could exist.”

The Hungarian officers, many of whom had been mechanical experts in their own right, could only stare in awe at the sheer abundance of parts, tools, and equipment that seemed to flow endlessly through the depot. Their own military had operated under conditions of constant shortage—parts had to be crafted by hand when replacements were unavailable, and every repair was a challenge. But here, in the vast depots of Camp Atterbury, machines were treated as tools to be used and replaced, not treasured objects to be preserved.

Lieutenant Gabbor Sabbo, a Hungarian vehicle maintenance officer, recalled his first experiences working in the American repair shops. “In Hungary, we were trained to make repairs as best we could, often improvising when parts weren’t available,” Sabbo later wrote in a technical journal. “Here in America, they didn’t repair—they replaced. A broken engine? Remove it, put in a new one. It was that simple. The vehicle was back in action within hours.”

The idea of replacing rather than repairing was revolutionary for the Hungarian soldiers. To them, it seemed wasteful, almost obscene. But the American approach, they began to understand, was rooted in something much larger: efficiency, scale, and an industrial capacity that the Hungarian army could never hope to match. They had been taught that wartime production was about scarcity and sacrifice, but what they were witnessing was an entirely different logic—one that embraced abundance and standardized systems to achieve maximum output.

Even something as simple as tires left them stunned. Corporal Mihali Nagi worked in the depot’s tire shop, expecting to repair tires as he had in Hungary. “Instead,” Nagi said, “I found myself surrounded by new, not repaired, tires. Thirty-five thousand new tires. Not retreads. New. I thought I had misunderstood. But no, they simply replaced them when they wore out.”

It was moments like these that began to shape the Hungarian prisoners’ perceptions of their captors. They realized that the Americans’ ability to produce, to replace, and to organize their efforts on such a vast scale was not about wealth—it was about efficiency, about creating systems that worked together toward a common goal.

As the months passed, the Hungarian prisoners settled into their routines at Camp Atterbury. While still technically prisoners, they were treated with a respect that was foreign to them. They worked reasonable hours, received good food, and were allowed to learn about the American systems that had won the war. They became not just prisoners, but students of a new kind of industrial revolution.

Captain Andras Kalman, a Hungarian officer who had studied economics before the war, recognized the broader implications of what they were witnessing. “It wasn’t just about the machines,” he wrote. “It was about the system that ran them. We began to see the depot as a school, not just a military facility. It was a school where we were learning the future of industrial power.”

Major Fete and his men began to document everything they could—standardization practices, supply chain management, and quality control systems. They were not mere observers but active students, seeking to understand how they could apply these methods back home in Hungary after the war.

“We knew we couldn’t just bring back the American system wholesale,” Fete said. “But we could bring back the principles. The way they organized everything. The speed. The efficiency. We had to understand this if we were going to rebuild Hungary.”

By late 1945, the Hungarian prisoners had transformed themselves into a remarkable resource for the American military. They documented everything—the procedures, the workflows, the tools, and the philosophy behind it all. They took notes, created diagrams, and studied American repair manuals like sacred texts.

In return, the American military supported their efforts. They received technical journals, attended lectures from professors at nearby Purdue University, and even had access to advanced technical films. “We were not just learning to fix things,” Lieutenant Kalman later reflected. “We were learning how to fix our entire country.”

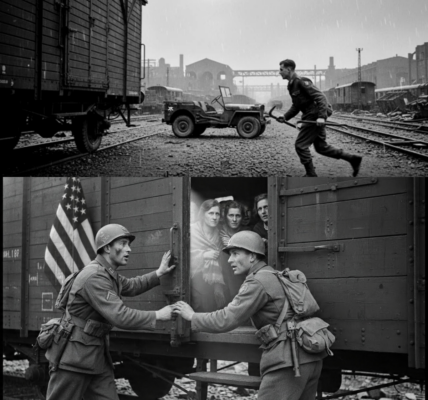

As the war drew to a close and the Hungarian prisoners faced the prospect of repatriation, the American authorities faced an unexpected challenge. Many of the prisoners had requested to stay longer to continue their studies, to learn more about the systems that had fascinated them for so long. The Americans, recognizing the long-term value of this unique situation, allowed them to remain under the new designation of “Surrendered Enemy Personnel.”

But in the spring of 1946, the time came for the Hungarian prisoners to leave Camp Atterbury. Major Fete addressed his men for one final time. “We are leaving as students, not as enemies,” he said. “What we take with us is more valuable than any material resources. We carry knowledge that can help rebuild our homeland.”

And rebuild they did. Many of the men who left Camp Atterbury went on to play significant roles in the post-war reconstruction of Hungary. They brought with them the lessons they had learned about efficiency, organization, and production—lessons that would influence Hungarian industry for decades to come.

Today, the legacy of the Hungarian prisoners at Camp Atterbury lives on. Their notebooks, filled with diagrams of American production methods and management techniques, are preserved in museums and archives across Hungary. These men, who had once fought against America, became some of the most ardent students of American industrial methods. They chose knowledge over immediate freedom, believing that true freedom came from the ability to build, to create, and to sustain.

Their story is a testament to the power of industrial capacity and knowledge transfer—how the lessons learned on the factory floors of Indiana helped shape the future of a nation torn by war. And in doing so, they left a legacy that continues to influence the world, long after the final chapter of their war was written.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.