“You Are Still Nurses” – German Women POWs Shocked by How America Treated Them

June 1945, a gray troop ship rocks against the waves of the Atlantic. Below deck, 147 German women sit in darkness. Nurses, prisoners, enemies of the most powerful nation on Earth. For 11 days, they have not slept. They have whispered the same questions over and over. Will they beat us? Will they starve us? Will they make us disappear? One nurse, 23-year-old Hannah Cleaner from Berlin, carries a small notebook.

Inside, she has written 312 names. Every soldier she watched die on the Eastern front. She wonders if her own name will soon be added to someone else’s list. The ship slows. The engines go quiet. A voice cracks over the loudspeaker. We have arrived. The women climb to the deck. Through the morning haze, they see it.

The skyline of New York City, the richest city in the world, the heart of the enemy. Armed guards line the gang plank. This This is it. The punishment begins now. But then something happens. Something that makes no sense. A woman in an American military uniform steps forward. She speaks to them in German. And what she says next will shatter everything they have been told about Americans.

What follows is not revenge, not cruelty. Not what anyone expected. Within months, these German prisoners will be saving American lives. A blinded marine will hand one of them his purple heart. A soldier with no legs will call his German nurse the reason I can walk again. And one nurse will keep a dying soldiers medal around her neck for 56 years. This is the story history forgot.

the story of enemies who became healers of hatred that became something else entirely. You are going to want to stay until the very end cuz what happens in those American hospitals will change the way you think about war, about enemies, and about what it truly means to be human.

Hit subscribe right now, drop a like, and let us take you back to 1945, to the moment everything changed. The war in Europe ended on May 8th, 1945. But for 147 German women, the nightmare was just beginning. These were not soldiers. They were nurses. Young women, most in their early 20s, who had spent years stitching wounds, holding dying hands, and watching boys bleed out on operating tables.

They had served in field hospitals on both the eastern and western fronts. They had worked under bombing raids. They had amputated limbs in tents that shook with every explosion. Now Germany had surrendered. The Third Reich had collapsed. And these 147 women found themselves prisoners of the United States Army.

Among them was Hannah Claner, a 23-year-old nurse from Berlin. She had joined the German Army Nursing Corps in 1941, just weeks after her nursing school graduation. By 1945, she had treated over 2,000 wounded soldiers. She had watched 312 of them die. She kept count in a small notebook. The numbers helped her feel something when emotions became too heavy to carry.

There was also Lizel Hartman, 24 years old, from Vienna. She had worked on the Eastern Front, where temperatures dropped to minus30° and frostbite killed as many men as bullets. She had once performed an emergency amputation by candle light when the generator failed. The soldier survived. She never forgot his screaming.

And there was Anna Vieber, 26, from Dresdon. She had been on duty the night the Allied bombs turned her city into an inferno. Over 25,000 people died in two nights of bombing. Anna had treated burn victims until her own hands blistered from touching charred skin. When American soldiers captured her 3 months later, she did not resist.

She was too tired to resist. These women, along with 144 others, were gathered at a processing camp in Bavaria in late May 1945. American military police separated them from other prisoners. A US Army officer told them they would be transported to America. He did not say why. He did not say for how long. He simply said to pack their belongings.

Most of them had no belongings left. On June the 1st, 1945, the nurses were loaded onto trucks and driven to a port in France. The air smelled of diesel fuel and ocean salt. Seagulls screamed overhead. The women climbed a metal gang plank onto a gray US Navy transport ship. The hull was cold under their fingers. The sound of boots echoed against steel.

Below deck, they were assigned bunks in a large compartment. The space was clean but crowded. Each woman received a thin mattress, a wool blanket, and a small pillow. The food was basic. Bread, canned vegetables, powdered eggs, but it was more than many of them had eaten in months. In the final weeks of the war, German rations had dropped to 800 calories per day.

Some nurses had survived on less. The voyage across the Atlantic took 11 days. For most of the women, it was the longest they had ever been at sea. The ship rocked and pitched in the waves. Many became seasick. The smell of vomit mixed with the salt air below deck. Sleep was difficult. Fear made it worse.

At night, the women whispered to each other in the darkness. What will the Americans do to us? Willwe be put in labor camps? Will we be punished for what Germany did? They had all heard the propaganda. German radio and newspapers had spent years telling them that Americans were cruel. That American soldiers showed no mercy, that prisoners in American hands were beaten, starved, humiliated.

The Nazi regime had painted the enemy as monsters. Now these women were sailing straight into the monster’s arms. Hannah Clean later wrote in her diary about those nights at sea. She recorded, “We did not know what waited for us. We only knew what we had been told, and what we had been told was terrifying.

I prayed every night, not for freedom, just for survival. Lizel Hartman remembered the silence. “No one talked during the day,” she later recalled. “We sat on our bunks and stared at the walls. But at night, I could hear women crying. Some prayed, some cursed. “We were nurses. We had saved lives, but we did not know if our own lives were worth anything now.

” The ship pushed westward through the gray Atlantic. Days blurred together. The women counted meals to track time. Some tried to remember their training. They were medical professionals. Perhaps that would matter. Perhaps that would save them. On the morning of June 12th, 1945, a voice came over the ship’s speaker.

Land had been cited. The women rushed to the deck. Through the morning haze, they saw the outline of a city rising from the water. tall buildings, cranes, a harbor filled with ships, New York City. Hannah Clean stood at the railing and stared. She had seen photographs of this place.

She had heard it was the richest city in the world. Now she was arriving not as a visitor, but as a prisoner. The ship slowed. Tugboats guided it toward the pier. The harbor smelled of fish and smoke and summer air. On the dock below, the women could see vehicles waiting, military trucks, buses, and something else.

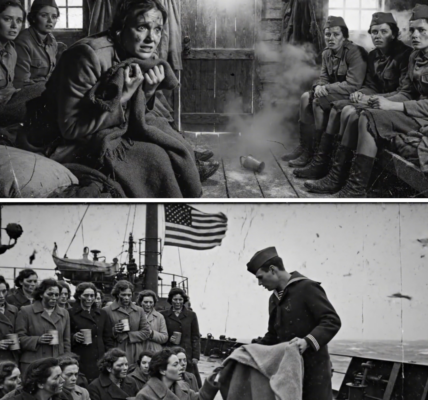

Red Cross ambulances lined up in a neat row. No chains, no armed guards pointing rifles at the gang plank. Just ambulances and buses. The women exchanged confused glances. This was not what they expected. This was not what they had been told. What happened next would shatter every belief they had carried across the ocean. The gang plank lowered with a heavy metallic clang.

The sound echoed across the water like a gunshot. 147 German nurses stood frozen on the deck, staring down at American soil. Armed soldiers lined both sides of the walkway. Their uniforms were crisp. Their boots were polished. Their faces showed no emotion. The German women began walking down single file, their footsteps unsteady on the metal ramp.

The June sun was warm on their skin. The air smelled of salt, gasoline, and something else. Something cooking nearby that made their empty stomachs ache. At the bottom of the gang plank, a woman in an American military uniform stepped forward. She was tall with graying hair pinned beneath her cap.

Her posture was straight, her expression firm, but not cruel. This was Colonel Margaret Harper, a senior officer in the US Army Nurse Corps. She had been assigned to oversee the German prisoners. Colonel Harper raised her hand. The German nurses stopped walking. Silence fell over the dock. Then she spoke in German.

You are prisoners of war, she said. Her accent was imperfect but clear. But you are also nurses. You will be sent to military hospitals across the United States. There you will assist in the care of wounded American soldiers. You will be treated with the respect due to medical personnel under the Geneva Convention. The women stared at her.

Some did not believe what they heard. Respect from the enemy. This had to be a trick, a lie to make them cooperate before the real punishment began. But there was no punishment. Instead, the women were guided toward a row of waiting vehicles, not prison trucks, not armored transports. Red Cross ambulances and civilian buses with cushioned seats.

The doors opened. American personnel helped them climb aboard. No one shouted, no one shoved, no one pointed a weapon. The buses drove north into New Jersey. The ride took less than an hour. Through the windows, the German nurses watched the American landscape roll past. green trees, paved roads, neat houses with gardens and parked automobiles.

Everything looked untouched by war. No bombed buildings, no rubble, no refugees walking with bundles on their backs. Hannah Claner pressed her forehead against the cool glass. She thought of Berlin, where entire neighborhoods had been reduced to dust. She thought of Dresden, where Anna Vber had watched 25,000 people burn. And here was America, whole and clean and impossibly peaceful.

The buses stopped at a military processing center. The building was large and white, surrounded by trimmed lawns. Inside, the German nurses were divided into groups and led to examination rooms. American nurses, women in pressed uniforms, conducted thorough medical checks. They took temperatures. They checked blood pressure. They examined eyes, ears,teeth, and skin.

The process was professional, clinical. There was no roughness, no humiliation. After the examinations, the women were taken to a supply room. There, neatly folded on tables were new uniforms. American nurse uniforms, white dresses with matching caps, stockings, leather shoes in multiple sizes. Each German nurse was measured and given clothing that fit.

Lizel Hartman held up her new dress. The fabric was soft. The stitching was perfect. She had not worn anything this clean in over a year. On the eastern front, she had patched her uniform with scraps from dead soldiers coats. Now she was holding clothing that looked like it came from a department store.

Next came the showers, hot water, real soap, towels that were thick and white. Anno stood under the stream and let the heat soak into her muscles. She could not remember the last time she had bathed with warm water. In the final months of the war, German hospitals had no fuel for heating. Nurses washed with cold water from buckets.

Sometimes they did not wash at all. After the showers, the women were led to a dining hall. Long tables were set with plates, forks, and napkins. American kitchen staff brought out trays of food, roast chicken, mashed potatoes with butter, fresh green vegetables, bread rolls still warm from the oven, and for dessert, apple pie with coffee and real cream.

Hannah Clean sat down. She looked at the plate in front of her. Her hands trembled. In Germany, civilians were surviving on 1,000 calories per day. Soldiers at the front had received even less. She had once gone three days eating nothing but stale bread and turnip soup. She picked up her fork and took a bite of the pie.

The sweetness spread across her tongue. The crust was flaky. The apples were soft and warm. And then the tears came. She did not sob. She did not make a sound. The tears simply rolled down her cheeks and dripped onto the table. She was not crying from sadness. She was crying because someone had fed her like a human being.

Around the room, other women were crying too, quietly over their plates of chicken and potatoes, over their cups of real coffee. They cried because this was not punishment. This was kindness. And kindness, after years of war, felt almost unbearable. That night, the nurses slept in clean barracks with real beds, sheets, pillows, blankets that did not smell of blood or smoke.

Hannah whispered to her bunkmate in the darkness. They gave us uniforms like we are still nurses, her friend replied softly. They gave us dignity. The next morning, the women learned their assignments. They would be split into groups and sent by train to hospitals across the country, Kansas, California, Illinois, New York. Their job would be to care for wounded American soldiers.

The same men who had fought against Germany. This was not a gift. It was a test. And what happened in those hospitals would prove whether enemies could become something more. The trains left New Jersey on June 15th in 1945. Seven different trains heading in seven different directions. Each carried a group of German nurses toward American military hospitals that desperately needed help.

The war had ended in Europe, but the wounded kept arriving. Every day, transport ships docked at American ports, carrying broken soldiers from the battlefields of France, Belgium, and Germany. Young men with missing arms, shattered legs, faces burned beyond recognition, minds destroyed by what they had seen. Hospitals were overwhelmed.

The wards were full. The American nurses worked double shifts and still could not keep up. By June 1945, over 670,000 American soldiers had been wounded in the European theater alone. Another 250,000 had been wounded fighting in the Pacific. The hospitals needed 12,000 additional nurses just to meet basic care standards.

They had fewer than 8,000, so the German prisoners became workers. Hannah Clean’s train headed west toward Kansas. She sat by the window and watched America pass by. Endless farmland. Golden wheat fields stretching to the horizon. Small towns with white churches and main streets lined with shops. Children playing in yards.

Women hanging laundry on clothes lines. Everything was untouched, whole, alive. Hannah thought about the train rides she had taken across Germany in 1944. bombed out stations, destroyed bridges, refugees crowded into cattle cars with everything they owned tied in bed sheets. She had seen a child freeze to death on a platform in Munich because the train was delayed 12 hours in the snow.

Here the American train had cushioned seats, a dining car serving sandwiches and coffee, clean bathrooms. The contrast was almost too painful to understand. Lazel Hartman’s train traveled to California. Three days across the entire country, she watched deserts turn into mountains, then mountains into green coastal valleys. She had never imagined a nation so vast, so untouched by war.

In Austria, her hometown of Vienna had been bombed 17times. Over 12,000 civilians had died. Here, the cities glowed with electric lights at night. Anna Weber went to Illinois. Her train passed through Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana. Everywhere she looked, she saw factories running at full speed, smoke stacks pouring out clouds of steam, rail yards filled with freight cars.

America had not just survived the war. It had grown stronger because of it. She later wrote, “I realized then that we never had a chance. Germany was fighting a nation that could build faster than we could destroy.” On June 18th, the trains began arriving at their destinations. The German nurses stepped off onto platforms where military personnel waited with trucks and instructions.

The women were tired, nervous. They still wore their American nurse uniforms. They still did not fully believe they would be treated as medical staff. At a military hospital outside Topeka, Kansas, Hannah Clean and 14 other German nurses were led through the front entrance. The building was massive, three stories tall, over 400 beds.

The hallways smelled of disinfectant and bandages. Somewhere deeper inside, someone was screaming. The head nurse, Captain Dorothy Wells, met them in the lobby. She was a stern woman in her 40s with sharp eyes and no patience for nonsense. She looked the German women up and down. “You will work 6 day weeks,” she said. “Hour shifts.

You will follow orders from American medical staff. You will treat every patient with professionalism. You are prisoners, but you are also nurses. Act like it. Then she handed each woman a name badge and a ward assignment. Hannah was assigned to ward C amputees. Her hands shook as she pinned the badge to her uniform.

She followed an American nurse down a long corridor. The floor was polished tile. The walls were painted pale green. Through open doors, she could see rows of hospital beds, men lying motionless, men with stumps where legs used to be, men with bandages covering half their faces. The American nurse stopped at a doorway.

This is your ward. 42 patients. Most lost limbs at the Battle of the Bulge or during the Rine Crossing. Some have infections. Some have phantom pain. All of them have been through hell. She paused and looked directly at Hannah. They know you’re German. Some will refuse your care. Some will say ugly things. Do your job anyway. Then she walked away.

Hannah stood alone in the doorway. Inside the ward, dozens of eyes turned toward her. American eyes, soldiers who had fought against her country. Men who had watched their friends die at the hands of German bullets and bombs. One man, a sergeant with both legs amputated below the knee, stared at her uniform, then at her face, then he spat on the floor.

“They’re making us get cared for by Nazis now,” he said loudly. “What’s next?” “Hitler himself comes to fluff my pillow.” A few men laughed. Most stayed silent. The tension in the room was thick enough to choke on. Hannah took a breath. She walked into the first bed. a young private maybe 19 years old with his right arm missing at the shoulder.

His chart hung on a hook at the foot of the bed. She picked it up and read it. Infection dressing change needed twice daily. Morphine every 4 hours for pain. She looked at him. He looked away. She set the chart down. I am here to change your bandages, she said in halting English. The private said nothing. Hannah gathered her supplies.

clean gauze, antiseptic, scissors, tape. Her hands moved automatically. She had done this a thousand times before on German soldiers, on Russian prisoners, on dying boys who called for their mothers in languages she did not speak. She began to unwrap the bandages on the private shoulder.

He flinched but did not pull away. The wound beneath was red and raw. She cleaned it gently, applied fresh antiseptic, wrapped it in new gauze with precise, careful folds. When she finished, the private finally looked at her. His eyes were hard, suspicious, but he nodded once. It was not trust, but it was not hatred either. It was a beginning.

The first week was the hardest. In Kansas, Hannah Clean worked her 8-hour shifts in silence. She changed bandages. She adjusted morphine drips. She cleaned wounds that smelled of infection and rotting tissue. She did not speak unless spoken to. She moved quietly between beds like a shadow. Most patients ignored her.

A few muttered insults under their breath. One man refused to let her touch him at all. He demanded an American nurse every time she approached. Captain Wells allowed it. She simply reassigned Hannah to other patients who did not object. But on the fifth day, something changed. The young private with the missing arm, the one whose bandages Hannah had changed that first day, was running a fever.

His wound had become infected. The skin around the stitches was hot and swollen. He needed constant monitoring. Hannah checked his temperature every 2 hours. She applied cold compresses to his forehead. She cleaned his wound threetimes that day, each time more carefully than the last. She did not speak. She simply worked.

By evening, the fever broke. The private’s temperature dropped back to normal. He opened his eyes and saw Hannah standing beside his bed, checking his chart. “You stayed,” he said. His voice was rough and tired. Hannah nodded. “You needed care.” He was quiet for a long moment. Then he said, “Thank you.” It was the first time an American soldier had thanked her.

Across the country in California, Anna Weber faced a different kind of challenge. She had been assigned to the burn ward at a naval hospital in San Diego. The patients there were Marines who had fought in the Pacific. Many had been burned by flamethrowers on Iuima and Okinawa. Their injuries were severe. Some had lost fingers.

Others had faces so scarred they could barely open their mouths to eat. The smell in the burn ward was unforgettable. charred skin, antiseptic ointment, the sickly sweet odor of healing flesh. It turned Anna’s stomach the first time she entered, but she had smelled worse. In Dresden, she had treated burn victims pulled from buildings that were still smoking.

She had held the hands of women whose skin came off in sheets. On her third day, Anna assisted in surgery. A 21-year-old Marine needed skin grafts on his chest and arms. The American surgeon, Major Richard Callaway, was exhausted. He had performed 11 surgeries in 3 days. His hands shook slightly as he prepared his instruments. Anna stepped forward.

I can assist, she said. Major Callaway looked at her. He hesitated, then he nodded. Have you done this before? Many times, Anna replied. During the operation, Anna handed him instruments before he asked for them. scalpel, forceps, sutures. Her movements were smooth and practiced. She had worked in field hospitals where there was no time to think, only to act.

Her hands remembered. When the surgery ended, Major Callaway pulled off his gloves and looked at her. You’ve got good hands, he said. Steady hands. Anna allowed herself a small smile. I was trained well, he paused. Where did you work before? The Eastern Front, she said. and Dresdon. His expression shifted.

He knew what had happened in Dresdon. The firebombing, the 25,000 dead. He nodded slowly. “Then you’ve seen hell.” “Yes,” Anna said. “Just like these boys in Illinois.” Lizel Hartman was assigned to a rehabilitation ward. Her patients were men learning to walk again with prosthetic legs, learning to use artificial arms, learning to live in bodies that no longer worked the way they once did.

Among them was a sergeant from Texas named William Crawford. He had lost both legs at the Battle of the Bulge when a German shell hit his foxhole. He was 28 years old. Before the war, he had been a ranch hand. Now he could not stand without help. Lazil worked with him everyday. She helped him practice with his new prosthetic legs. She held his arms when he tried to stand. She caught him when he fell.

And he fell often. Sometimes he cursed. Sometimes he threw things. Once he shouted at her, “I wouldn’t be like this if it wasn’t for you people.” Lizel did not respond with anger. She simply helped him back into his wheelchair. But one afternoon, after Crawford had successfully walked 15 steps across the room, he stopped and looked at her.

His face was red from effort. Sweat ran down his temples. “I hated Germans,” he said quietly. “Thought you were all monsters,” Lazil met his eye. She did not look away. Crawford continued. But you’ve got gentle hands, patient hand. Lizel’s voice was soft. We were told the same thing about Americans, that you were monsters, that you showed no mercy.

Crawford nodded slowly. And now, now I think, Lysel said, that war makes liars of everyone. By autumn 1945, the hostility had faded in most wards. Not completely, not everywhere, but enough. The German nurses were no longer strangers. They were no longer just the enemy in uniform. They were the woman who sang quietly while changing bandages.

The one who stayed late when a patient was in pain. The one who remembered how each man liked his pillows arranged. In one hospital in Ohio, a nurse named Greta Hoffman had been working with amputees for 3 months. One day, a corporal asked for her by name. Not just any nurse, Greta specifically, because he said she knew how to wrap his stump without it hurting.

In Kansas, Hannah’s patients began saying good morning when she arrived. In California, Anna was invited to assist in more surgeries. In Illinois, Crawford told Lysil she had hands like his grandmother, strong but kind. These were small victories, quiet ones. But in the space between enemy and friend, they mattered more than any treaty ever could.

By December 1945, something remarkable was happening in American military hospitals. The lines between captive and captive were beginning to blur. It started with small things, gestures so quiet they almost went unnoticed. In Kansas, Hannah Cleanarrived at Ward C one morning to find a cup of coffee waiting on the nurse’s station desk. It was still hot.

A folded note sat beside it. The handwriting was shaky but readable. for the nurse who doesn’t sleep. Thank you. Bed 14. Bed 14 was the young private she had cared for during his infection, the one whose fever she had monitored through the night 3 months earlier. He had saved part of his breakfast ration to make sure she had coffee.

Hannah stared at the cup. In Germany, coffee had been rationed to 50 g per person per month by 1944. Most civilians went without entirely. Here, a wounded American soldier was sharing his portion with a German prisoner. She drank it slowly. Every sip tasted like forgiveness. In Illinois, the men in Lizel Hartman’s rehabilitation ward had been watching her for weeks.

They noticed she never complained, never took extra breaks, never asked for anything. She worked her shifts, ate her meals in the staff cafeteria, then returned to the small barracks where the German nurses were housed. One evening in late November, Sergeant Crawford called her over to his bed. Around him sat five other patients in wheelchairs.

All of them were amputees. All of them had been in her care for months. Crawford held out his hand. In his palm was a small wrapped package tied with string. “We pulled our cigarette rations,” he said. “Took us 3 weeks. Got you something for Christmas.” Lizel unwrapped the package carefully. Inside was a chocolate bar, a real Hershey’s bar.

In 1945, cigarettes were currency in military hospitals. Soldiers traded them for favors, for extra dessert, for magazines and writing paper. A full carton could buy almost anything. These men had pulled their rations for weeks to purchase a single chocolate bar. Lizel’s hands trembled. “I cannot accept this,” she whispered. “Yes, you can,” Crawford said firmly.

You’ve earned it. Another soldier spoke up. You stayed with me when I had nightmares. When I woke up screaming, “You didn’t have to do that.” A third added, “You treat us like we matter. Like we’re still men, not just broken parts.” “Lizel looked at each of them.” Then she broke the chocolate bar into pieces and handed one to every man in the circle.

“Then we share it,” she said, like a family. They sat together that evening, enemy and ally, eating chocolate in a rehabilitation ward in Illinois while snow fell outside the windows. But perhaps the most powerful gesture came from California. In the naval hospital in San Diego, Anna Weber had been caring for a 22-year-old Marine named Thomas Garrett.

He had been blinded by shrapnel on Okinawa, both eyes destroyed. His world was now permanent darkness. For 4 months, Anna had guided him through the ward. She described everything he could no longer see. The color of the sky outside his window, the shape of clouds, the way sunlight moved across the floor. She read him letters from his family in Vermont.

She helped him learn to eat, to dress, to navigate his bed and chair without sight. Thomas had been angry at first, angry at the war, angry at the Japanese, angry at God. But he was never angry at Anna. She was the one constant voice in his darkness. Calm, patient, present. One afternoon in December, Thomas asked her to sit beside his bed.

“Anna,” he said, “I need you to do something for me.” “Of course,” she replied. He reached under his pillow and pulled out a small wooden box. Inside was his purple heart medal, the decoration given to soldiers wounded in combat. He had received it 3 months earlier, but had never opened the box. “I can’t see it,” Thomas said quietly.

“I’ll never be able to see it.” “But you can.” He held the box toward her. “I want you to have it. Carry it for me.” “So someone who understands what it cost can keep it safe.” Anna’s breath caught. “Thomas, I cannot take this. This is yours. You earned this.” “I earned it by getting hurt,” Thomas said.

“You earned it by putting people back together. You’ve seen the same hell I have, maybe worse. You deserve to carry something that says you survived. Anna took the box with shaking hand. Inside the purple ribbon and bronze medal gleamed in the winter light. She had cared for hundreds of German soldiers.

She had watched them die. She had never received a medal, never received thanks from her own government. Only orders, only demands. Now an enemy soldier, a man blinded by her nation’s allies, was giving her his most precious possession. She closed the box and placed her hand over Thomas. “I will keep it safe,” she whisped. “I promise.

” Across the country, similar moments unfolded. Patients writing letters home that mentioned the German girl with kind eyes. Soldiers defending their German nurses when new patients made cruel remarks. a corporal in Ohio who learned basic German phrases just to make his nurse smile. By Christmas 1945, over 89% of American patients in hospitals with German nursing staff reported positive interactions.

Medicalofficers noted a marked improvement in patient morale and recovery rates in wards where the German nurses worked. This was not propaganda. This was not a military strategy. This was simply what happens when people choose to see each other as human beings instead of enemies. War had made them strangers, but pain, care, and small acts of kindness were making them something more.

The war officially ended on September 2nd, 1945 when Japan surrendered. But for the 147 German nurses working in American hospitals, their war had already transformed into something else entirely. something none of them expected, something that would change them forever. By early 1946, the question arose, what should be done with these women? They were still prisoners of war.

Technically, they could be sent back to Germany, but Germany in 1946 was a ruined nation. The country had been divided into occupation zones controlled by America, Britain, France, and the Soviet Union. Over 7 million Germans were homeless. Food supplies had collapsed. In some cities, the average civilian consumed only 900 calories per day, half the amount needed for survival.

Tuberculosis and typhus were spreading unchecked. But the American military faced a choice. Send the nurses back to that devastation or allow them to remain where they were needed. Colonel Margaret Harper, who had first greeted the women at New York Harbor, submitted a report to the War Department in January 1946. She wrote, “These German medical personnel have served with distinction and professionalism.

They have provided essential care to thousands of American soldiers. Many patients have specifically requested their continued service. I recommend they be allowed to remain in the United States as medical workers until such time as Germany can adequately receive them.” The recommendation was approved. The 147 nurses would stay.

But something deeper was happening beyond bureaucratic decisions. The women themselves were changing. The hatred and propaganda they had carried across the ocean were dissolving in the daily work of healing. Hannah Clean later wrote in a letter to her sister in Berlin. I came here believing Americans were cruel. I was wrong.

I have seen more kindness in this enemy nation than I ever saw in my own. The soldiers I care for have every reason to hate me. Instead, they call me by name. They ask about my life. They treat me like a person, not a monster. I do not know what this means for Germany, but I know what it means for me. It means everything I was taught was a lie.

Lizel Hartman described her transformation differently. In a 1947 interview, she said, “On the Eastern Front, I stopped seeing patients as people. They were just bodies, wounds to close, pain to stop. I had to turn off my heart to survive. But here, working with these American boys, my heart turned back on. They made me feel again.

They reminded me why I became a nurse in the first place. Not to serve a country, to serve people. Anna Weber kept Thomas Garrett’s Purple Heart Medal in a small pouch she wore around her neck. She never took it off. In later years, she said it was the most important thing she owned.

That medal taught me, she explained, that enemies are only enemies until someone chooses to stop fighting. Thomas could not see my face, he could only hear my voice and feel my hands. And that was enough for him to trust me. We spend so much time hating people we have never met. But when you meet them, when you truly see them, the hate disappears.

The American soldiers were transformed too. Sergeant William Crawford, the Texas ranchhand who had lost both legs, was discharged from the hospital in March 1946. Before he left, he wrote a letter to the hospital commander. It read, “I want it on record that my nurse, Lizel Hartman, is the reason I can walk again. Not just because she taught me to use prosthetics, because she made me believe I was still worth something.

She was my enemy. Now she is my friend. If we can do that, maybe the whole world can. In California, Major Richard Callaway, the surgeon who had worked with Anna Weber, submitted a formal commendation. He recommended Anna be recognized for her medical skill and dedication. The commendation was approved. Anna Weber became the first German prisoner of war to receive an official commendation from the United States Army Medical Corps.

By mid 1946, over 12,000 American soldiers had been treated in wards where German nurses worked. Post discharge surveys found that 91% of those patients reported positive or neutral feelings toward their German caregivers. Some maintained correspondence with the nurses for years afterward. This was not reconciliation on a grand political scale.

It was reconciliation at the human level. One bandage at a time, one shared chocolate bar, one whispered thank you in a dark ward. In 1947, the German nurses were given a choice. They could return to Germany or they could apply to remain in the United States asimmigrants. 73 chose to go home. 74 chose to stay. Hannah Clean stayed.

She became a registered nurse in Kansas and worked at the same military hospital until 1968. She married an American veteran in 1950. She never returned to Germany. Lazel Hartman returned to Austria in 1948. She spent the rest of her life working in a rehabilitation hospital in Vienna. She stayed in contact with Sergeant Crawford until his death in 1989.

Anna Weber stayed in California. She kept Thomas Garrett’s purple heart until her death in 2001. In her will, she returned the medal to his family with a letter that read, “This belonged to the bravest man I ever knew. He taught me that blindness is not in the eyes, but in the heart. I carried it for 56 years.

Now I return it with gratitude.” The story of these 147 women is not widely known. It does not appear in most history books, but it should because it reveals a truth more powerful than any battle that compassion, not conquest, wins the longest wars. They had crossed the Atlantic as enemies. They had arrived expecting cruelty and found kindness.

Had they had worked among the wounded and discovered that pain has no nationality. In the end, America’s greatest weapon was not its bombs or its bullets. It was its ability to see the humanity in those it defeated. The 147 German nurses who arrived in America in June 1945 carried with them the weight of propaganda, trauma, and fear.

They expected punishment. They received respect. They expected hatred. They received care. and in return they gave everything they had learned in the worst years of the war, skill, compassion, endurance to the very soldiers who had defeated their nation. This was not a political gesture. It was a quiet revolution.

Proof that even in the aftermath of the most destructive war in history, individual human beings could choose a different path. They could choose to heal instead of harm, to forgive instead of judge, to see each other not as Germans or Americans, but simply as people trying to survive the same suffering.

In that choice lies the only victory that truly matters.