Why Viet Cong Scouts Ranked Australian SAS Above MACV-SOG and US LRRPs

The Americans were loud. The Australians, they vanished. And when they returned, men were gone. These weren’t our words. They were theirs. The Vietkong scouts who tracked Western forces through Fuakti Province. The men and women who moved through the jungle like smoke. Who read the ground like text.

Who could smell a cigarette from 200 m and hear a radio click through the canopy. They feared one unit above all others. Not the most aggressive, not the most heavily armed, but the quietest. The Australian SAS. In capture documents and post-war interviews, VC reconnaissance cadres spoke plainly about the differences. American infantry easy to detect. Boots pounded trails.

Radios crackle constantly. The smell of soap and cigarettes preceded them by half a kilometer. May CV sogg dangerous, unpredictable, aggressive. They struck like lightning and disappeared. But they were loud when they moved. You could hear them coming if you listen carefully enough. US LRRPs, fastm moving, wellarmed, professional.

They covered ground quickly and efficiently. But they still moved with that American rhythm, that confident forward momentum that disturbed the jungle. The Australians. One VC tracker put it this way. They read the ground. They moved like us. Sometimes we didn’t know they were there until it was too late. Dense triple canopy jungle.

Mangrove swamps. Rubber plantations cut through with trails that had been used for centuries. Humidity so thick you could taste it. Rain that came in walls. Ground that held sign for days if you knew how to read it. Perfect terrain for small team warfare. Perfect terrain for men who understood silence. Picture this moment reconstructed from field reports and VC accounts.

AVC scout is moving parallel to what he believes is an American patrol. He’s positioned himself 30 m off their likely route, moving carefully through the undergrowth, stopping every few steps to listen. He hears nothing. That should have been his first warning. He moves closer, confident, ready to mark their position and report back.

He’s done this dozens of times. Americans are predictable. He freezes at the base of a banyan tree. Through the foliage 6 m away, he sees movement. Four shapes barely visible, moving in single file. They’re not dressed like Americans. The shapes are wrong. The spacing is wrong. The silence is absolute. One of them stops. Hand signal.

The others freeze instantly. No sound. No broken branches. Nothing. The scout doesn’t breathe. Doesn’t move. His heart hammers against his ribs because he’s just realized something terrifying. They’ve been here longer than he has. They pass within 6 m. He never sees their faces. Just shapes in the green. And then they’re gone, absorbed back into the jungle like they were never there at all.

He waits 20 minutes before moving. When he returns to his unit, he says only, “Australians, we don’t follow them.” This wasn’t an isolated incident. This was the pattern that emerged again and again in Fuaktui between 1966 and 1971. The pattern that made VC scouts the smartest, most capable trackers in the theater, quietly ranked the Australian SAS as the most dangerous Western unit they encountered.

Not because the SAS won more firefights, not because they had better weapons or air support, but because they operated in the one way VC scouts respected most, silence, patience, restraint, and undefeated small team bushcraft. This is that story. Before we understand why the Australians earned this respect, you need to understand who these VC scouts actually were.

They weren’t regular infantry. They weren’t even typical gerillas. They were the elite eyes and ears of Vietkong operations. The smartest, calmst, most disciplined fighters in the local force and main force units. Many were local villagers who’d grown up in these jungles. They knew every trail, every water source, every piece of dead ground.

Some had fought the French. Some had fathers who’d fought the French. And yes, many were women. This fact was often underestimated by Western forces. But VC reconnaissance cadres frequently included women who moved through the countryside with even less suspicion than men who could gather intelligence in villages and then disappear into the jungle to guide main force units.

They carried minimal gear. An AK-47 or SKS carbine, perhaps 50 rounds, a water bottle, rice balls, a hammock and mosquito net. That was it. No radios unless absolutely necessary. No heavy packs, nothing that made noise or slowed them down. Their job was simple. Detect Western forces before being detected themselves, mark their position and strength, and report back so main force units could either ambush or avoid them.

VC scouting doctrine was built on principles that went back to the Vietmin campaigns against the French. Move silently, not just quietly, silently. Every step deliberate, every branch memorized. Move like water through the jungle, leaving minimal sign. Read the ground constantly.

Look for brokenspiderw webs, crushed leaves, boot impressions in mud, bent grass that hasn’t sprung back. The jungle tells you everything if you know its language. Detect by all senses. Sound travels far in the jungle, especially foreign sounds. Smell reveals position. Soap, cigarettes, gun oil, insect repellent. Even rhythm betrays presence. Western forces moved with a different cadence than locals.

Never engage unless absolutely necessary. Your value is in what you see in report, not what you kill. A dead scout tells no one anything. By 1967, VC scouts had worked out remarkably accurate profiles of most American units, standard movement patterns. US forces tended to use trails and existing paths.

They moved in predictable formations. They set night positions and defensible clearings. All of this could be anticipated. Boot signatures. American combat boots left distinctive tread patterns in mud and soft ground. Different from Vietnamese sandals or bare feet. Easy to identify and track. Radio discipline. American units used radios constantly.

Even encrypted tactical frequencies produce detectable radio interference. Scouts with simple detection equipment could pinpoint a radio operator from hundreds of meters away. Patrol rhythms. US units operated on schedules. Morning movement. Midday breaks, evening positions. This predictability was exploited ruthlessly. Noise and smell. This was the big one.

Americans smelled different. Soap, deodorant, cigarettes, gun oil, crash, and coffee. They sounded different. Metal on metal, zippers, boot eyelets clicking, radio static, whispered English. One VC veteran said it plainly in a postwar interview. We could smell Americans before we saw them. We could hear them from 100 meters.

Finding them was easy. Avoiding them was easy. And then came the Australians, specifically the SAS squadrons rotating through Fuak Tur, small four-man patrol teams who operated differently from any Western force the VC had encountered. Fourman teams, not platoon, not squads. Just four highly trained men moving independently for days at a time.

Smaller signature, easier to hide, harder to detect. Total silence, no talking, hand signals only. Weapons taped to prevent rattling, no smoking, no unnecessary movement. They communicated like VC scouts communicated through gesture and intuition. Rubber sold boots. SAS often wore canvas and rubber jungle boots similar to what Vietkong wore or even Vietnamese sandals.

Their footprints looked wrong to scouts expecting American boot treads. Indigenous pacing. This was critical. SAS moved at scout pace. Slow, deliberate, stopping frequently to listen. Not the confident forward momentum of American infantry. They moved like hunters, not soldiers. Shape discipline. SAS troopers understood how to break up their silhouette in the jungle.

They didn’t look like western soldiers when seen through foliage. They looked like shadows, irregular shapes, nothing the eye could lock onto. No predictable patterns. They didn’t use trails. They didn’t set night positions and clearings. They moved unpredictably, doubling back, circling, using terrain that seemed impassible.

They operated the way VC main force units operated. A VC scout interviewed decades later said, “The Americans fought like Americans. The Australians fought like us. That was the problem.” your audience. Older Australians who know these jungles, who served in or near these units, they understand this immediately.

They know bushcraft isn’t about technology or firepower. It’s about patience, observation, and the discipline to stay quiet when every instinct screams to move, to talk, to do something. The SAS had that discipline in abundance, and the VC scouts recognized it instantly. Late 1967, somewhere in the northern sector of Fuakt Thai Province near the Longhai Hills, a three-man VC scout team has been tracking what they believe is a US LRP patrol for most of the afternoon.

They picked up the sign 3 km back. Fresh boot impressions in the mud near a stream crossing, broken undergrowth, disturbed leaf litter. The pattern looked right. Four to six men moving northwest. probably heading toward a night position near a ridgeel line where they could set up observation. The lead scout, we’ll call him Min, though that’s not his real name, has done this before.

He’s tracked American patrols dozens of times. LRPS are good, better than regular infantry, but they follow patterns. They move with purpose. They cover ground efficiently. He’s positioned his team 30 m off what he estimates as their route, moving parallel, staying down wind. The plan is simple.

Confirm their night position, count their numbers, report back to the local force commander. Maybe set up an ambush for tomorrow morning when they break camp. But something feels wrong. Min stops at the base of a mahogany tree, hand raised. behind him. The other two scouts freeze. Silence. Not just quiet. Silence.

The kind of silence that means something is holding its breath.No birds, no insects. The jungle is gone still. That should only happen when something large is moving nearby, disturbing the natural rhythm. But Min hasn’t heard anything. No bootsteps, no equipment noise, no whispered English. He looks at the ground. The bootprints continue ahead, clear and fresh, less than an hour old.

So, where are they? He moves forward carefully, every sense alert. The humidity is crushing. Sweat runs down his face, but he doesn’t wipe it away. Any movement could give him away. Through the foliage ahead, he sees a break in the canopy, a creek, maybe four meters wide, moving slowly over rocks. The bootprints lead straight to it.

Min positions himself behind a stand of bamboo, perhaps 15 m from the creek. Perfect observation position. He settles in to wait. Whoever he’s tracking will cross soon. He’ll see them, count them, maybe even hear radio traffic. He waits 5 minutes, 10, 20, nothing. And then movement, not from ahead, from his left. Four shapes materialize at the creek edge, maybe 12 m from men’s position.

They weren’t there a moment ago. They didn’t walk up. They were just suddenly there. Not Americans. The silhouettes are wrong. The spacing is wrong. They’re wearing bush hats, not helmets. Their uniforms break up differently in the dapple light. And they’re moving with hand signals, completely silent. Each man covering a different arc of fire.

Australians. Men’s chest tightens. He doesn’t move, doesn’t breathe. Behind him, he can sense the other two scouts have seen them as well, frozen in place. The four Australians don’t rush the crossing. The lead man, the scout, moves to the water’s edge and pauses. Looks upstream, looks downstream, listens.

Full 30 second pause. Then a hand signal. The second man moves to the creek. Weapon up. Covering. He steps into the water slowly, carefully, placing each foot to avoid splashing. Moves across in perhaps 45 seconds. Takes up position on the far bank. Weapon covering back across the creek. Then the third man.

Same careful movement, same silence, not a single unnecessary sound. Then the fourth. They’re not hurrying. They’re not worried about being caught in the open. They move with absolute confidence and patience. Each man knowing exactly what the others will do. Once across, they pause again. Another full minute of listening.

Then a hand signal and they melt back into the jungle on the far side. Within seconds, they’re invisible. Min stays frozen for another 5 minutes. Then slowly, carefully, he backs away from his position, hand signaling the other scouts to withdraw. They move 200 m before stopping. One of the other scouts whispers, “Americans.” Min shakes his head.

“Australians, SAS, I think. Do we follow? Men looks back the way they came. The bootprints they’d been tracking. Those were decoys or they’d picked up the wrong sign or something. The Australians had somehow gotten ahead of them without being detected. Had crossed terrain. The VC scouts thought they knew perfectly.

Had moved close enough to observe the creek crossing before the VC had even arrived. No, Min says quietly. We don’t follow Australians. Let’s break down what just happened from the VC perspective. LRPS would have moved faster. American long range patrol teams were good, but they prioritized covering ground.

They would have crossed that creek in under 2 minutes and kept moving. The SAS took 5 minutes and didn’t make a sound. SOG would have set an ambush. If Mac Visog had detected VC scouts tracking them, they would have doubled back and set up a kill zone. They were aggressive, offensiveminded. The SAS simply moved through, apparently unconcerned.

The SAS had been there first. This was the part that disturbed men most. The bootprints he’d been following weren’t fresh Australian tracks. They were something else, or they’d been misdirection. The SAS had somehow gotten to that creek crossing before the VC scouts arrived, despite the VC having intimate knowledge of every trail and path in the area.

That meant the Australians were reading the terrain as well as or better then the VC scouts themselves. That night, back at the temporary camp, Min reports to his commander, “We tracked a western patrol, Australians, SAS, possibly. They cross the creek in the northern sector. Did you mark their position? No.

Why not? Min pauses, choosing his words carefully. They move like we do. They’re quiet, patient. Following them is He searches for the right word. Dangerous. More dangerous than following Americans. His commander nods slowly. He’s heard similar reports. Two months ago, an entire VC scout section lost contact with headquarters while tracking what they thought was an Australian patrol.

They were never heard from again. Whether they were killed, captured, or simply got lost trying to follow men who moved like ghosts, no one knows. Mark them in the daily report, the commander says. But you’re right. We don’t follow Australians. We avoid them when possible. This becomes theunofficial doctrine in Fuaktui. Track Americans, ambush Americans when you can.

But Australians, mark their presence and stay clear. By mid 1968, the VC had perfected a simple but effective technique for confusing Western reconnaissance patrols. Plant false sign on known trails and paths. Then observe how different units react. The technique worked like this. Take a well-used trail. Deliberately disturb it in ways that suggest recent enemy movement.

Broken branches at head height, fresh bootprints, crushed undergrowth, maybe even a deliberately abandoned piece of equipment like an empty magazine or a discarded bandage. Most American units would see the sign, report it, and either call in an air strike or set up an ambush position nearby. Either way, they’d revealed their position and intent.

The VC could then avoid that area, or if they were bold, set up a counter ambush. LRPS were harder to fool, but even they sometimes took the bait. They’d investigate cautiously, but they still followed the logic of the false sign. SOG teams sometimes ignored obvious sign entirely, assuming it was a trap. But that made them predictable in a different way.

You could use false sign to herd them toward where you actually wanted them to go. And then the SAS arrived. This encounter takes place along a trail network northwest of Newiot base in an area where both VC and Australian patrols operated regularly. A fourman VC scout team has spent 2 hours carefully planting false sign along a trail that runs parallel to a creek bed.

They have made it look like a VC supply column of maybe 15 men moved through here heading southeast perhaps 12 hours ago. Fresh footprints in the mud, broken branches, disturbed leaf litter, a piece of rope left behind, the kind used to tie supply bundles, even a small cooking site carefully staged to look like it was hastily abandoned.

The VC scouts then withdraw 200 meters and take up observation positions in dense undergrowth overlooking the trail. They’re not planning an ambush. They’re just watching to see how western forces react to the sign. This is intelligence gathering, learning enemy patterns. They wait. Just after noon, one of the scouts signals movement.

Four shapes barely visible approaching from the northeast. The scouts stay completely still, weapons ready but not raised. Their job is to observe, not engage. The lead Australian stops perhaps 30 m from the false sign site. He doesn’t walk up to it. He just stops, crouches low, and watches. The other three spread out slightly, providing security, but they’re not looking at the trail.

They’re looking everywhere else. Full minute of absolute stillness. Then the lead man moves forward slowly. 10 m. Stops again. Studies the ground, doesn’t touch anything. Another pause. From their position, the VC scouts can’t see exactly what he’s doing, but they can read his body language. He’s not excited.

He’s not calling anyone forward. He’s just studying. The lead Australian, let’s call him the patrol scout because that was his role, is reading the sign the way you’d read a badly written letter. Something about it doesn’t sit right. The bootprints are clear. Too clear. They’ve been placed, not walked. The broken branches are the right height, but they’re broken in the wrong direction.

Whoever did this broke them while facing back toward where the column supposedly came from, not while walking forward. The cooking site looks abandoned, but the ash is cold gray, not cold black. That means it was made with dry wood gathered elsewhere, not fresh wood from the surrounding area. No one stopping for a quick meal in enemy territory gathers perfectly dry wood.

They use whatever’s close and the rope. That’s the giveaway. It’s lying in the middle of the trail, loosely coiled. If someone dropped it by accident, it wouldn’t coil. If they abandoned it deliberately, they’d throw it into the bush, not leave it where it could be useful to an enemy. This is theater. Someone wants this sign to be found.

The scout makes a hand signal. The other three move up to his position, still not approaching the false sign directly. Brief whispered conference. Maybe 30 seconds. Then a decision. Instead of following the trail, instead of moving toward the obvious sign, they do something the VC scouts watching have never seen a western unit do.

They circle completely around the site, moving 200 m out in a wide arc, crossing terrain that’s significantly more difficult. Dense undergrowth, thorny vines, muddy ground. They’re not avoiding the sign because they think it’s trapped. They’re avoiding it because they know it’s false and they’re looking for whoever placed it.

From their observation position, the VC scouts watch the Australians disappear into thick jungle on a bearing that will bring them within 50 m of the VC position. Pure dread washes over the team leader. These Australians didn’t just identify the false sign. They extrapolated where whoever placed itwould logically observe from.

He signals immediate withdrawal. Slow, careful, silent. They can’t risk staying. If the Australians detect them now, the VC scouts will be the ones caught in the open, not the other way around. They move back 500 m before stopping, hearts pounding. Let’s understand what just happened. Americans would have reported it.

Standard US infantry would have called in the sign, probably requested an air strike on the suspected VC position, revealed their own location in the process. LRRPs would have investigated cautiously. They would have approached carefully, checked for booby traps, maybe followed the false trail for a while before realizing something was off.

Sog might have ignored it entirely. They’d assume it was a trap and bypass it, but they wouldn’t have done what the SAS did. The SAS read through the deception. They identified it as false sign, extrapolated the deception’s purpose, and then use that knowledge to locate the observers. That’s not just tactical competence. That’s thinking like the enemy thinks.

That’s understanding the psychology behind the deception. That evening, the VC scout team leader reports to his commander. the false sign site on the Creek Trail. Australians encountered it and they identified it as false. They circled around looking for us. We had to withdraw. The commander is quiet for a moment.

They read the ground better than we do. Yes, that admission from a VC scout who grew up in these jungles, who learned tracking from his father, who fought the French, who has successfully deceived dozens of American patrols. That admission carries weight. The VC scouting doctrine is based on one fundamental assumption. We know this ground better than anyone.

We can read sign better than the enemy. We can see them before they see us. The SAS just shattered that assumption. Over the following months, other VC scout teams report similar encounters. Australians who don’t fall for ambush bait. Australians who identify false sign. Australians who somehow anticipate where VC observation posts will be positioned.

The psychological impact is significant. VC scouts begin to question their own assessments. When they see sign on a trail, is it real or planted by the Australians? When they choose an observation position, have the Australians already factored that into their root selection? This is the kind of warfare where the mental game matters as much as the physical one.

and the SAS are winning the mental game. A post-war interview with a former VC Reconnaissance Cadre member captures it perfectly. We could predict Americans. We could not predict Australians. They thought the way we thought. Sometimes they thought better. That last sentence, sometimes they thought better. That’s the highest compliment one professional scout can give another.

This encounter takes place in late 1969 in the province east of New Dot, an area where VC main force units had been operating with increasing boldness. A US infantry company, approximately 120 men, is conducting a sweep operation through a valley bordered by low ridges. They’re moving carefully but predictably, following standard doctrine.

point element, main body, rear security, flanking elements spread out to prevent ambush. They don’t know it yet, but they’re being herded. A six-man VC scout team has been shadowing them since dawn, staying 300 m out, parallel to their route. The scouts have done this dance before. They’re guiding the Americans toward a prepared kill zone 2 km ahead.

A narrow section of the valley where the ridgeel lines close in, perfect for an L-shaped ambush. The main VC force, perhaps 80 fighters, is already in position, dug into the RGEL line with interlocking fields of fire, RPGs positioned to hit the lead and rear elements, machine guns sighted to sweep the kill zone, escape routes prepared and rehearsed.

It’s a textbook ambush, and the Americans are walking straight into it. The VC scout team leader, we’ll call him Trowong, is confident. He’s done this successfully twice before. The Americans move predictably. They trust their firepower and air support. They think their size makes them safe. Truang’s team is positioned on the southern ridge about 200 m above the valley floor, concealed in dense undergrowth.

From here, they can observe the American advance and signal the main force when to spring the ambush. But first, they need to make sure there are no other Western units in the area, no helicopters inbound, no artillery registered on the ridge lines, no complications. Truong scans the opposite ridge through a small pair of binoculars. Chinese-made, poor quality, but functional.

He’s looking for any sign of movement, any indication that the Americans have sent a flanking unit or reconnaissance element ahead. Nothing. The opposite ridge is quiet, dense jungle, no movement, no indication of any western presence. He’s satisfied. Everything is proceeding as planned. What Truang doesn’t know, what he can’tknow is that four Australian SAS troopers have been positioned on that opposite ridge since before dawn.

They’re not there to protect the American company. They’re on their own reconnaissance patrol, completely separate operation. and they happened to move through this area yesterday afternoon. They identified it as a likely ambush site, perfect terrain for it, and decided to observe for 24 hours to see if VC forces would use it.

And sure enough, the VC have the SAS team watched the VC main force move into position during the pre-dawn hours. They counted approximately 80 fighters, noted their positions, marked their escape routes. They’ve been lying in the bush for 6 hours now, completely motionless, observing through the dense canopy. They’re positioned about 40 m above the valley floor, concealed in a thicket of wait a while vines and secondary growth.

From here, they have an oblique view of both the VC positions and the approaching American company. The patrol commander, a sergeant with two tours in Vietnam, faces an interesting tactical problem. He can’t warn the Americans directly without revealing his position and compromising his patrol. Radio traffic would be detected.

Any attempt to move would alert the VC. He makes a command decision. Observe. Report after the fact. Prepare to extract if things go badly. This is pure SAS doctrine. Don’t compromise the patrol. Don’t reveal your position. Gather intelligence and live to fight. Another day. Truong is still scanning the opposite ridge when something catches his eye.

Not movement, not a shape, just something. A slight irregularity in the pattern of shadows and light. Something that doesn’t quite belong. He focuses his binoculars on the spot, studies it for 30 seconds. Nothing, just jungle. But the feeling persists, that instinct every scout develops. The one that says something is wrong even when you can’t see it.

He shifts his position slightly, changes his angle of view, and there just for a moment, a different shadow pattern. Not natural. His stomach drops. Someone is watching. Has been watching. Is watching right now. He lowers the binoculars slowly, mind racing. Who? When? How long? The Americans below are still a kilometer from the kill zone, moving steadily forward.

The main VC force is waiting for his signal. Everything is in position except except someone on that opposite ridge knows everything. Truong faces an impossible choice. If he signals the ambush now before the Americans are in the kill zone, the VC force will lose the advantage. If he waits until the Americans are in position, but someone is already observing, the ambush might be compromised from the start.

And if those watchers are Australians, and Truong is increasingly certain they are because only Australians position themselves this way. Only Australians have the patience to lie silent in the jungle for hours. Then they’ve probably already radioed for artillery or air support. The smart move is to call off the ambush.

Signal the main force to withdraw. Except that today’s opportunity is gone because somehow, impossibly, the enemy got here first. From their position, the SAS sergeant is watching both the American company and the VC scouts on the opposite ridge through a starlight scope. He can’t see the VC main force positions. They’re too well concealed. But he doesn’t need to.

He’s been doing this long enough to know exactly where they’ll be based on terrain and standard VC doctrine. He’s also fairly certain the VC scouts on the opposite ridge have just realized they’re being observed. One of them shifted position slightly, the way someone does when they’ve spotted something that makes them nervous.

The sergeant signals his scout, a hand gesture. They know. The scout nods acknowledgement. They stay absolutely still. Don’t move. Don’t reveal exact position. Let the VC stew in uncertainty. This is the psychological warfare element of reconnaissance. It’s not about shooting. It’s about letting the enemy know they’ve lost the initiative without ever firing a shot.

Truong makes his decision. He signals the other VC scouts withdraw. Then he signals down to the main force. Abort. It takes 15 minutes for the signals to filter through and for the VC main force to begin their withdrawal. They’re well trained and disciplined. They pull back in good order, moving into pre-planned escape routes, dispersing into the jungle.

By the time the American company reaches the area where the kill zone would have been, the VC are gone. The Americans never know how close they came. They never know that 80 fighters with RPGs and machine guns were waiting for them. They sweep the area, find some fighting positions that might be a week old or a day old, report possible enemy contact, and keep moving.

The SAS patrol waits until nightfall before moving. They’ve been in position for nearly 12 hours, most of it spent completely motionless. Now they extract slowly, carefully, moving perpendicular to boththe American route and the VC escape routes. By midnight, they’re 3 km away, setting up a night position in thick secondary jungle.

Tomorrow, they’ll move to an extraction point and report what they observed. Their patrol report will note approximately 80 VC main force prepared ambush positions canceled ambush when they detected observation. No contact grid coordinates provided for future operations dry factual professional. No heroics, no firefight, just intelligence work.

Let’s examine what happened from the Vietkong perspective. SOG would have intervened. If Macy Vog had observed this setup, they would have called in an immediate strike. Gunships, artillery, whatever was available. They were aggressive, offensiveminded. They would have tried to destroy the VC main force while they were in position.

LRPS might have tried to warn the Americans. They would have broken radio silence, tried to coordinate a response, attempted to turn the tables on the ambush. The SAS did neither. They simply watched, observed, gathered intelligence, let the VC know they were being observed without revealing exactly where the observers were or how many of them there were.

This is terrifying from a VC perspective because it means the Australians were in position before the VC main force arrived. They had the discipline to watch for 12 hours without moving. They didn’t reveal their position even when they could have scored a significant tactical victory. They prioritized intelligence gathering over immediate action.

They extracted without ever being definitively located. Here’s what makes this encounter different from the others. The VC scouts weren’t outsmarted by bushcraft or sign reading. They were out positioned by strategic patience. The SAS didn’t get lucky by stumbling onto the ambush site. They identified it as tactically significant and proactively positioned themselves to observe it.

That’s thinking two steps ahead. That’s understanding terrain and enemy doctrine so well that you can predict where they’ll operate before they arrive. A postwar interview with a former VC commander includes this observation. The Americans wanted to kill us. The Australians wanted to understand us. That made them more dangerous.

That sentence captures something essential about why the VC scouts respected the SAS. It wasn’t fear of firepower. It was respect for professional competence. The SAS operated the way the VC themselves aspired to operate. Quietly, patiently, professionally, with strategic patience, and tactical discipline. We’ve seen three encounters now, three different scenarios where VC scouts encountered Australian SAS patrols and came away shaken or impressed or both.

But why? What was it specifically about the SAS that earned this respect? Let’s break it down systematically because your audience, men who understand soldiering, who understand the jungle, who might have served in these very areas. They want to understand the tactical and psychological reality. This was the first and most important factor.

When the Americans arrived in Vietnam in large numbers in 1965 to 66, the VC initially struggled to adapt. American firepower was overwhelming. American mobility, helicopters, mechanized infantry, artillery support was unlike anything the VC had faced against the French. But within months, the VC adapted. They learned American patterns.

They realized that American forces, for all their technological advantages, were predictable in their movement, predictable in their responses, predictable in their doctrine. The Australians arrived and immediately operated differently. They didn’t use the same patrol sizes. They didn’t move the same way.

They didn’t rely on firepower first. They operated more like the Vietmen had operated against the French. Small units, independent action, minimal support, maximum stealth. VC scouts recognized this immediately because it was their own operational style being mirrored back at them. A captured VC document from 1968 includes this note.

Australian patrols do not operate like American patrols. They should be treated as indigenous forces, not as foreign troops. That’s a remarkable assessment. The VC are essentially saying these aren’t foreigners fighting a foreign war. These are professional soldiers who’ve adapted to the environment. Western military culture, particularly American military culture, emphasized momentum.

Keep moving. Stay aggressive. Maintain the initiative. This works brilliantly in conventional warfare. It works less well in guerrilla warfare, where patience is often more valuable than aggression. The SAS understood this. Their fourman patrols would spend hours in a single position just observing.

They’d move 200 m in a day if that’s what the tactical situation required. They’d wait in ambush positions for days without firing a shot if that’s what the mission demanded. This kind of patience was something VC scouts understood viscally because it was how they operated.Waiting in a position for 6 hours, not moving, barely breathing, just observing.

That was standard VC scout procedure. Seeing Western soldiers do the same thing was unsettling. It meant they couldn’t be predicted by normal patterns. It meant they might be anywhere, already in position, already watching, one VC veteran said in an interview. We respected their endurance. They could wait like we could wait. That’s unusual for Westerners.

This seems obvious, but it’s worth emphasizing. The primary job of a VC scout was to detect enemy forces before being detected themselves. They were very, very good at this. They had successfully tracked and monitored American units countless times. Their detection rate was extraordinarily high. And then the Cess showed up and somehow managed to regularly avoid detection even when VC scouts were actively looking for them.

the creek crossing encounter we discussed earlier. The VC scouts completely lost track of the SAS patrol. They thought they were following Americans and the Australians somehow got ahead of them without being seen. The false sign encounter. The SAS not only detected the deception but extrapolated where the scouts would be observing from the ghost ambush.

The SAS were in position on that ridge before the VC scouts even arrived and remained undetected for 12 hours. This wasn’t luck. This was systematic, practiced, professional field craft at the highest level. From a VC perspective, this was the equivalent of meeting another master craftsman in your own field. You recognize the skill immediately because you know how hard it is to achieve.

American doctrine in Vietnam generally relied on mutual support. Infantry companies operated with artillery support. Patrols had helicopter extraction available. Nobody operated truly independently for extended periods. SOG teams pushed this envelope. But even they had sophisticated support networks, forward operating bases, dedicated air assets, reaction forces on standby. The SAS operated differently.

Fourman patrols would go out for five, six, seven days at a time with minimal support. No guaranteed extraction. No artillery support most of the time. Just four men, their weapons, their packs, and their skills. This was closer to how VC main force units operated. Small groups moving independently, relying on their own capabilities.

no backup unless they could reach another VC unit. The VC scouts recognized this. These weren’t soldiers who could call in an air strike whenever they got in trouble. These were soldiers who had to rely on fieldcraft and tactical judgment because they were genuinely alone out there. That commanded respect.

One VC reconnaissance cadre member put it this way. They moved like hunters, not like an army. We understood hunters. This was the skill that impressed VC scouts most directly because it was their own primary skill. The ability to read ground, to see bootprints and know how old they are, how many people passed, how fast they were moving, whether they were carrying heavy loads.

The ability to read vegetation. To see which plants recover quickly from disturbance and which don’t. To know what broken branches mean. To spot camouflage positions. The ability to move without leaving sign, to step on rocks instead of soil to avoid breaking. Spiderwebs to move through vegetation without disturbing it permanently.

SAS troopers were trained in these skills to a level that matched or exceeded what most VC scouts could do. They had learned from Aboriginal trackers in Australia. They’d learned from their own jungle warfare school. They’d learned from experience in Borneo during confrontation. When a VC scout realizes that the enemy can read sign as well as he can, it’s psychologically destabilizing.

Because your primary advantage, intimate knowledge of the terrain and tracking skills is suddenly matched. The false sign encounter perfectly illustrates this. The SAS patrol scout didn’t just see the false sign. He analyzed it, understood it was false, and deduced its purpose. That’s master level sign reading.

This one is subtle but important. Sogg teams were known for aggressive action. If they detected enemy, they often engaged, ambushed, disrupted. Their mission was often direct action. Kill or capture enemy personnel, destroy supply caches, create chaos. LRPS were similar, though more focused on reconnaissance, but they’d still engage if they had the advantage.

The SAS had a different priority. Intelligence first. Don’t compromise the patrol unless absolutely necessary. Avoid contact if possible. Observe, report, extract. This meant SAS patrols would sometimes let VC units pass without engaging, even when they had clear shots. They’d watch, count, note equipment and morale and direction of travel, then report all that intelligence rather than taking a single kill.

From a VC scout perspective, this was simultaneously frustrating and impressive. Frustrating because you knowthey were there, but they didn’t reveal themselves. impressive because it showed immense tactical discipline. The ghost ambush encounter shows this perfectly. The SAS could have called in strikes on 80 VC fighters in prepared positions.

That’s a significant tactical opportunity. Instead, they observed, let the VC realize they were being watched and extracted with intelligence about VC operating patterns and positions. That’s playing the long game. That’s valuing information over body count. There’s one more factor worth mentioning, though it’s harder to quantify.

The Australians brought less cultural baggage to the conflict. Americans often struggled with the cultural and environmental reality of Vietnam. They were fighting a war that didn’t make sense in traditional terms, in an environment that was hostile against an enemy who wouldn’t fight fairly. Australians, and this is a generalization, but one that appears in multiple VC accounts, seemed more comfortable with the ambiguity.

They weren’t trying to win hearts and minds. They weren’t trying to rebuild a nation. They were professionals doing a specific job, patrol this area, find the enemy, report their positions, disrupt their operations. That narrower focus, that professional attitude came across in how they operated.

No frustration, no anger, no cultural superiority, just competent professional soldiers doing their job. VC scouts responded to this because it was how they saw themselves. Professionals doing a job, not ideologues fighting a crusade. So when you add all these factors together, non-standard tactics that couldn’t be predicted, patience and silence that matched VC operational style, ability to avoid detection consistently, small unit self-sufficiency without relying on support, bushcraft skills that matched indigenous trackers, tactical restraint and intelligence

first priorities, professional non-emotional approach to warfare. What you get is a unit that the VC scouts recognized as peers. Not superior, not inferior, but peers. Professional soldiers who understood the jungle, understood small unit tactics, understood patience and fieldcraft. And in a war where most Western forces operated in ways that were fundamentally foreign to VC operational culture, that recognition of peer competence carried enormous weight.

A final quote from a post-war interview with a former VC reconnaissance commander. We could defeat Americans with tactics. To defeat Australians, we had to be better than they were. And that was very difficult. That’s respect. Hard-earned, professionally recognized respect between enemies who understood each other’s capabilities.

April 1975, Saigon falls. The war that shaped a generation, that tore countries apart, that killed millions. It’s over. Australian forces had already withdrawn years earlier. The SAS squadrons rotated home, returned to Swanborn, went back to training and readiness and waiting for the next deployment. For them, Vietnam was a chapter, a successful chapter.

They had operated at the highest level, earned a reputation, lost men, but never lost a patrol, came home as professionals who’ done their job. For the Vietkong scouts who’d track them, who’d watch them, who’d learn to respect them, the Australians were a memory, a particular kind of memory, not enemies remembered with hatred, but professionals remembered with acknowledgement.

Starting in the 1980s and continuing through the 1990s and early 2000s, Western historians and journalists began conducting interviews with former Vietkong and NVA personnel. These weren’t propaganda exercises. They were genuine attempts to understand the war from both perspectives. And in those interviews, a pattern emerged.

When asked about which Western forces they feared or respected most, former VC scouts consistently mentioned the Australians. Not every time, not universally, but often enough that it formed a clear pattern. They moved like us. We couldn’t predict them. They understood the jungle. They were patient. They read the ground.

These phrases appear again and again in documented interviews. Not hyperbole, not exaggeration, just professional assessment from people who knew what they were talking about. Here’s what’s remarkable. These former VC scouts didn’t speak of the Australians with anger or bitterness. They spoke with something closer to professional respect.

War is complicated. The Vietnamese suffered enormously. Millions died. Entire landscapes were destroyed. The trauma lasted generations. But individual soldiers, individual scouts and trackers and reconnaissance professionals. They recognized each other as craftsmen in the same trade. One former VC scout interviewed in 2003 said it like this.

The Australians were the only Westerners who fought like true jungle fighters. They adapted. They learned. They respected the environment. We could understand them. There’s no reconciliation there. No forgiveness necessarily. Just recognition. theacknowledgment that on the tactical level, in the jungle, in the day-to-day reality of reconnaissance and counter reconnaissance, the Australians played the game at the highest level.

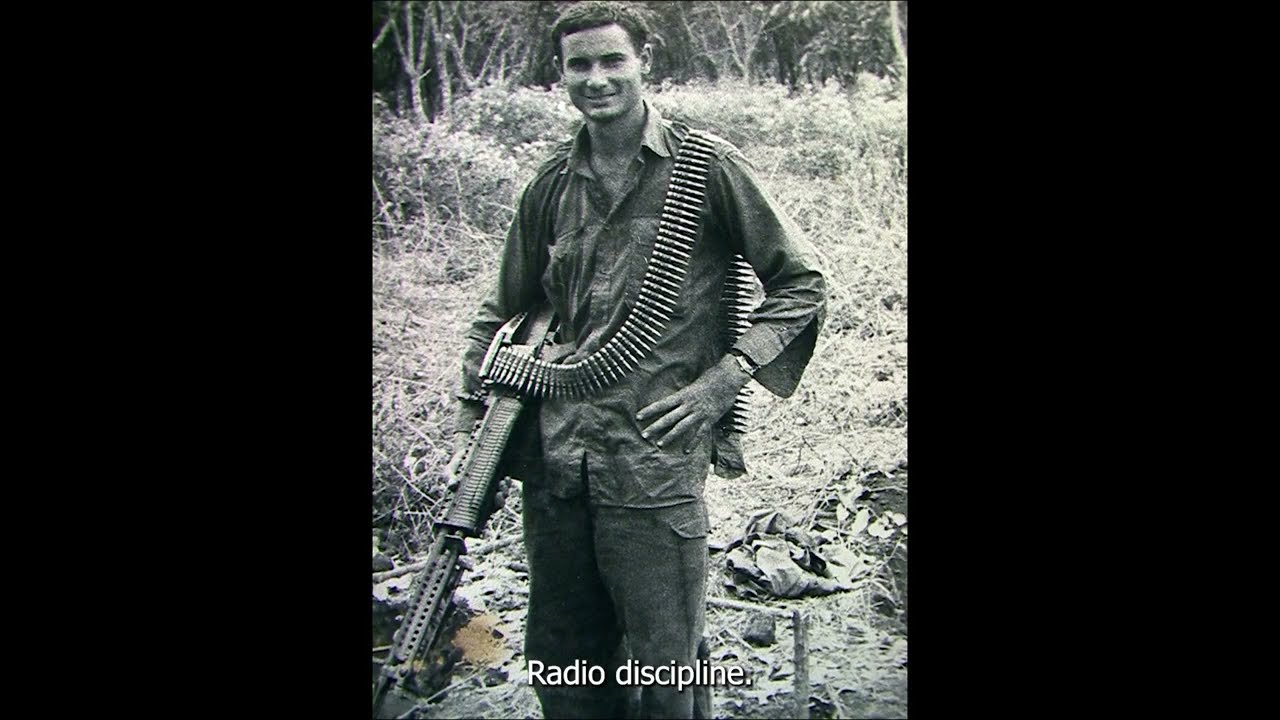

For the SAS troopers who served those tours, men who are now in their 70s and 80s, if they’re still with us, this recognition probably means something different than it means to historians or enthusiasts. They didn’t go to Vietnam seeking the enemy’s respect. They went because it was their job. They were professionals.

They had trained for years to operate in exactly these conditions. They executed their missions, brought their mates home, and returned to Australia. But knowing that the enemy recognized their competence, knowing that professional soldiers on the other side understood what they were doing and respected how well they did it.

That’s a particular kind of validation. Not the validation that comes from medals or promotions or public recognition. The validation that comes from knowing your enemy took you seriously. Many older Australians remember hearing these stories. Maybe not the specific details we’ve covered here, but the general reputation. The SAS and Fuakui, small patrols, no contact unless necessary.

Intelligence work. Professional, quiet, effective. Some of you listening to this served with or near SAS units. You remember seeing them at New Dot or at the airfield or coming back from patrol, quiet, bearded, looking more like bushmen than soldiers. Some of you were in other units, infantry, armored artillery. And you remember the scuttlebutt, the stories that filtered through the Australian forces about these fourman patrols that operated like ghosts.

Some of you lost mates in Vietnam. Maybe not in SAS, but in other units, other operations. And this story isn’t meant to diminish their service or suggest that only SAS were effective. Every unit had its role. Every man who served served honorably. But this particular story about scouts and counter scouts, about the professional respect that emerged between enemies, this story is worth telling because it captures something essential about how Australians fought in Vietnam.

Not with overwhelming firepower, not with technological superiority, not with massive manpower, but with discipline, skill, patience, and professionalism. There’s a certain kind of pride that comes from knowing your enemies took you seriously. Not bombastic pride, not flagwaving pride, quiet pride, the pride of a craftsman who knows his work was good.

The SAS in Vietnam earned that. They operated at the highest level in the most difficult environment against a highly skilled enemy. And that enemy, when the war was over and the propaganda was set aside and professional soldiers could speak honestly, they acknowledged it. They moved like us. That’s five words. But from a VC scout, from someone who spent years mastering jungle movement and sign reading and silent hunting, those five words carry weight.

For many older Australians, Vietnam is remembered through the lens of mates, the men you served with, the bonds formed under pressure, the trust required when four men go into the jungle for a week with no support. The SAS embodied that matesship at its most essential. Fourman patrols required absolute trust. Each man’s life depended on the others competence and discipline.

There was no room for weakness, no room for error, no room for anything except professional excellence and mutual trust. Some of those men didn’t come home. Some did, but carried the war with them in ways that took decades to process. Some came home and quietly went back to civilian life, rarely speaking about what they’d done.

This story is for all of them, the ones who are still here and the ones who aren’t. the ones who talk about it and the ones who don’t. Because even if they never knew that VC Scouts spoke of them with respect, even if they never heard these postwar interviews, even if they never thought about it in these terms, they earned it.

Let me leave you with one final image. It’s early morning in Puaktui Province. Thick mist hangs in the valleys. The jungle is waking up. Birds calling, insects humming. the day beginning. Four shapes move through the bush slowly, carefully. No talking, hand signals only. They’re in position before the sun burns off the mist.

They’ll stay there all day if necessary, just watching, observing, gathering intelligence. 200 m away, a VC scout is also watching. He’s seen sign that suggests Western forces in the area. He’s positioned himself carefully, using terrain and vegetation for concealment. For 6 hours, neither side moves. Neither side knows for certain the other is there, but both suspect. Both wait.

Both demonstrate the patience and discipline that defines professional reconnaissance. As the sun sets, the four Australians withdraw silently. Mission complete. Intelligence gathered, patrol intact. The VC scout watches them disappear or thinks he does. He’s notentirely certain they were there at all, but he reports it anyway.

Possible Australian patrol, Northern Sector. They move like us. That last sentence again. They move like us. Professional respect between enemies. Hard earned over. 5 years of operations acknowledged decades later when the guns had fallen silent and honest assessment became possible. The Australian SAS in Vietnam.

Quiet professionals who operated at the highest level and earned the respect of the one enemy whose opinion mattered most. The professional soldiers who tracked them, watched them, and understood exactly how good they were. That’s the story. That’s the legacy. And for the men who were there, whether they wore green and gold or black pajamas, the memory remains.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.