Why the Germans Feared the “Maple Leaf Regiment” More Than Any Other Allied Unit

December 1943, Ortona, Italy.

The oil lamp in the German command post didn’t give warm light. It gave nervous light—thin, flickering illumination that made every face look a little sick and every shadow look like a threat. Three kilometers behind the line, in a ruined building that still smelled faintly of flour and burned wood, Wehrmacht officers gathered around a wooden table buried under maps and reports.

Outside, the Adriatic wind carried salt and smoke. Inside, the air tasted like stale cigarettes and exhausted disbelief.

A major named Klaus Werner kept turning pages with hands that were supposed to be steady. The numbers on the paper made his fingers tremble anyway.

“They’re wrong,” someone muttered. “They must be wrong.”

But the numbers were stubborn. They didn’t care what an officer wanted to believe.

For six months, German defenses in Italy had held. They had shaped the campaign into a grind and made the Americans bleed for every ridge line. The British were predictable—methodical bombardment, daylight advances, pauses at night to regroup. German doctrine had been built around predicting enemy rhythm. If you know when the punch is coming, you can brace or sidestep or counter.

Italy had become a map of habits.

And then the Canadians arrived and broke the map.

Werner tapped a casualty summary from the last three weeks. “Our losses in sectors facing Canadian units are forty percent higher than anywhere else,” he said, voice low. He swallowed and pointed again. “In some engagements… sixty.”

Sixty percent wasn’t a statistic. It was a hemorrhage. It was a line collapsing. It was the kind of number that doesn’t just lose battles—it loses wars.

The First Parachute Division—Fallschirmjäger—considered itself Germany’s best. Elite soldiers, trained for years, veterans of brutal fights in Europe and Africa. They had stopped British armor. They had held against heavy American infantry assaults.

But against the Canadians, their standard tactics were failing.

Positions that should have held for days fell in hours. Strongpoints that should have extracted hundreds of Allied casualties were being overrun so quickly German officers didn’t have time to properly understand what had happened before the next report arrived.

Werner read from a field report written two days earlier, voice sounding strange in the stale room:

“A company commander observed Canadian infantry advancing through artillery fire that should have pinned them down. They did not stop. They did not seek cover. They moved forward as if the shells meant nothing. At close range the fighting became savage.”

Savage was the word the German officer used—the word the German mind understood. Savage meant irrational aggression, violence without calculation. Savage was how propaganda described enemies: either barbarians or cowards.

But then Werner’s voice hesitated, because the report didn’t match the usual story of “savage.”

“When our men attempted surrender,” he read, “the Canadians accepted immediately. Prisoners were treated correctly. Water was offered. Medical care provided. A Canadian officer—speaking perfect German—apologized for the conditions.”

That line made the room go quiet.

How can an enemy fight like demons and then behave like professionals?

German training manuals didn’t have a category for that. The enemy was supposed to be either weak or barbaric, disciplined or chaotic.

The Canadians were somehow both, switching modes so fast it made German commanders feel like they were fighting something that didn’t follow the rules of human behavior.

A colonel named Friedrich Braun spread reconnaissance photographs on the table. Aerial shots taken at different times.

He pointed at Canadian camp positions.

“Look at this,” Braun said quietly. “Daylight—quiet. Almost lazy. Tents. Cooking. Equipment idle.”

He slid another photograph forward.

“Night,” he said. “Empty.”

He tapped again, harder.

“Every night, they move,” Braun said. “Two in the morning. Four. Sometimes they do not attack, they simply appear, probe, vanish. Sometimes they strike. By dawn they hold objectives and it looks like they’ve been there all week.”

Traditional defense relies on knowing when the enemy sleeps.

But Canadians didn’t sleep on schedule.

“They strike when tired,” Braun said. “They rest when fresh.”

He looked up at the faces around the table.

“A German defender never knows whether the sector will remain quiet for three days… or explode in five minutes.”

That uncertainty is its own weapon. It doesn’t kill with bullets. It kills with exhaustion.

Men forced to stay alert every night break faster than men who fight one hard battle and then sleep.

The reports piled up.

Canadian artillery hitting targets on first shot beyond eight kilometers. Infantry clearing fortified buildings with speed that made German defenders feel overwhelmed before they could lift their rifles. Snipers positioned to cover streets firing into empty space because Canadians weren’t using streets.

They were moving through walls.

Werner pulled a diary from a captured Canadian soldier—mud-stained pages, a simple handwriting.

The soldier wrote about life before war: planting wheat in Saskatchewan, fixing tractors, simple country life.

Werner stared at the words, then at the casualty report attached to the diary.

This same “simple farmer” had stormed three fortified positions in five days, killed enemy soldiers, carried two wounded comrades to safety under fire.

The disconnect made no sense.

The most disturbing document lay at the bottom of the stack: a paragraph written by a German battalion commander—veteran of Russia—before dying of wounds.

Werner read it aloud:

“These are not the English. They give no quarter in assault, yet offer fair terms in surrender. One cannot predict their movements. They attack when exhausted, wait when strong. Fighting them is like boxing a shadow that suddenly turns to steel.”

When Werner finished, silence sat heavy on the table.

Braun closed the folder and said what everyone in the room already knew:

“High command dismissed earlier warnings. They called Canadians colonials. Adequate. Unremarkable.”

He looked at the casualty reports again.

“But we know different.”

They had counted the bodies.

Now they had to figure out how to fight an enemy that broke every rule they understood.

The answers began to emerge in January 1944.

But they brought no comfort.

Because the deeper the Germans studied Canadian tactics, the more it looked like they were watching the evolution of warfare in real time.

Not new weapons.

New behavior.

German observers timed Canadian building-clearance assaults and reported shocking speed. Where British units took roughly 140 seconds per room, and Americans around 160, Canadians were clearing rooms in 85 seconds on average in certain engagements—less than the time it took a man to properly process that he was about to die.

That small difference became enormous when multiplied across a street, across a town, across a campaign.

Faster clearing meant less time for defenders to organize. Less time to call reinforcements. Less time to set traps.

It meant fewer Canadian casualties and more German prisoners, because defenders who are overwhelmed quickly often choose surrender rather than slaughter.

The speed didn’t come from madness. It came from choreography.

First man through door goes left.

Second goes right.

Third covers center.

Grenade before boots cross threshold.

Rifle fire immediately after.

It happened like a grim dance—violent and efficient.

Germans inside those rooms described it later as feeling “hit by a wave.” Not because Canadians were stronger, but because Canadians were coordinated.

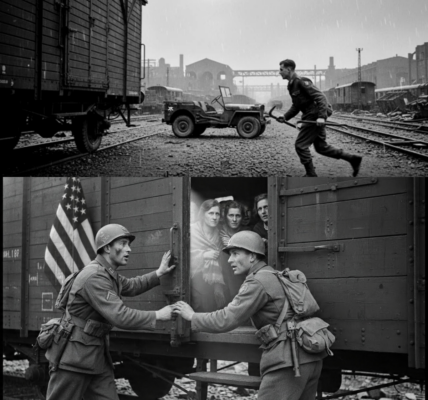

Then came Ortona.

December 20th, 1943.

Ortona sat near the Adriatic coast, stone buildings packed tight, narrow streets that created perfect machine-gun kill zones. German paratroopers fortified every structure, placing MGs to cover intersections, turning every alley into a funnel of death.

The Germans expected the Canadians to fight like everyone else: advance street by street, lose men to crossfire, grind forward slowly.

Instead, Canadians ignored the streets.

Engineers used explosive charges to blast holes through thick stone walls between buildings. Holes about a meter across—just enough for a man with full kit to squeeze through.

The Canadians called it mouse-holing.

They moved through entire blocks without ever stepping outside.

German machine gunners watched empty streets while Canadians advanced behind them through walls, appearing suddenly from angles that should have been impossible.

Urban warfare doctrine broke overnight.

Stone dust filled the air so thick men could barely see a few meters ahead. Explosions echoed constantly. Windows shattered. Walls cracked. The smell of cordite and burning wood never left. Soldiers wrapped cloth around faces to breathe. They fought inside buildings with flashlights and muzzle flashes as their only light.

The battle raged eight days.

By December 28th, Germans withdrew, leaving behind casualties far heavier than expected. German commanders had predicted maybe 300 losses while inflicting far greater Canadian casualties.

Instead, Canadians took Ortona at a cost that reversed German expectations.

Defense had become almost impossible not because Canadians were numerous, but because Canadians refused to fight on the defender’s terms.

Not everyone in Allied command loved this.

Some senior commanders believed in slow, methodical, artillery-heavy warfare. They saw Canadian aggression as reckless. They wrote memos complaining about “wasteful” methods.

But then a Canadian general—Guy Simonds—compiled after-action reports showing something that uncomfortable truth always shows:

A longer fight gives the enemy more time to kill your men.

A fast violent assault can shock defenders into surrender before they organize.

In war, “careful” sometimes means “giving the enemy time.”

Simonds bypassed objections and sent reports up the chain anyway.

And then, in February 1944, proof arrived from the enemy itself.

British intelligence intercepted a German communication—Tactical Directive 447—from 10th Army Command.

The directive ordered all German units to reinforce any defensive sector facing Canadian forces to one and a half times normal strength.

Not suggested.

Ordered.

If a position usually held with 1,000 soldiers, it now required 1,500 when Canadians were across the line.

That directive was a confession.

A formal admission that Canadian attacks were dangerous enough to require a 50% increase in defenders compared to facing equivalent Allied units.

German high command did not waste men on whim—especially by 1944.

If they demanded extra troops against Canadians, it meant Canadians had become a strategic threat, not a tactical irritation.

The German framework finally began to shift from confusion to reluctant understanding:

The Canadians weren’t irrational.

They were effective.

And effectiveness that cannot be predicted is terrifying.

By June 1944, Canadian forces moved to France and the hedgerow hell around Caen. The landscape became a slaughterhouse of sound: Lee-Enfields cracking sharp, 25-pounders booming like heartbeat every forty-five seconds, Bren guns clattering, engines roaring, men screaming.

No silence existed near the line. The noise followed men into sleep. It invaded dreams.

Then August 1944 arrived, and Canadians pioneered operations that made German officers feel like the ground had changed rules.

Operation Totalize: nighttime armored movement on a scale few believed possible—hundreds of tanks and vehicles advancing in darkness. German defenders couldn’t see what approached, only felt the ground shake under the weight of machines.

The 12th SS Panzer Division, elite and fanatical, was chewed down to a fraction of combat effectiveness in days. German high command met in emergency sessions and circulated memos describing Canadian formations as a disproportionate threat. They recommended avoiding engagement where feasible; when unavoidable, they demanded overwhelming force ratios against Canadians—even at the cost of weakening other sectors.

The maple leaf insignia became a warning, not a symbol.

A sign that told German soldiers: you are about to face something you cannot predict.

The “Canadian morale effect” appeared in German reports—surrender rates rising simply because Canadians were in the sector. Units facing Canadian offensives showed reduced effectiveness even before fighting began. Not cowardice—exhaustion and fatalism.

Because with Canadians, surrendering later offered no relief. Better to surrender sooner before the assault erased your position.

And then came the Falaise gap—artillery turning a valley into a furnace. Shells landing in continuous patterns. Smoke so thick afternoon became twilight. Heat from burning vehicles raising temperatures to unbearable levels. German soldiers described walking through hell.

Canadian infantry advanced through that nightmare wearing gas masks, methodically closing escape routes, clearing pockets, finishing the job.

War at its most industrial and brutal.

And still—within that horror—moments of humanity survived, as they often did with Canadians.

A basement where wounded from both sides sheltered together. A German medic treating Canadian wounded. Canadian wounded apologizing for creating work.

A farmhouse marked with a Red Cross flag—a German aid station. A Canadian patrol finding it and leaving morphine instead of taking revenge, marking the building so both sides would respect it.

A German doctor later wrote: “The enemy who fights most fiercely also shows unexpected mercy. We do not understand these men.”

That sentence captures the paradox Germans could not resolve:

How can soldiers be ruthless in assault and civilized in surrender?

The answer wasn’t paradox. It was moral clarity.

Canadians didn’t fight from hatred.

They fought for objectives.

They showed no mercy to resistance because hesitation cost lives.

But when surrender happened, the objective changed. The job became: secure prisoners, reduce suffering, move on.

Ruthless function, not cruelty.

Professionalism switched on like a light.

That ability—to move instantly from violence to restraint—was the most psychologically destabilizing thing for German defenders.

Because it meant Canadians were not acting from rage.

They were acting from control.

And an enemy who is controlled is harder to manipulate, harder to frighten, harder to exhaust into mistakes.

That is why German officers in Ortona stared at their casualty reports and felt fear.

Not because Canadians were monsters.

Because Canadians were calm.

And calm men, applying overwhelming force toward clear objectives, are the most dangerous opponents of all.

The lesson wasn’t only about Canada.

It was about what makes an army effective when everything becomes chaos.

Discipline matters. So does flexibility.

Training matters. So does initiative.

Rigid command structures give you order, but in real combat, opportunities appear and vanish quickly. Canadians proved that soldiers on the ground—corporals, sergeants—often see what distant commanders cannot. When allowed to exploit those openings, they change outcomes.

That philosophy—mission command, adaptive leadership—would later become modern doctrine in NATO and Western militaries. It sounded fancy later, but Canadians practiced it instinctively.

And yet, despite battle honors and tactical revolutions, most Canadian soldiers returned home and went quiet. Back to farms and small towns. Back to shops and schools. They rarely spoke about Ortona, Caen, the Scheldt, Falaise.

Their reputation stayed strongest among those who had fought against them.

Because enemies remember effectiveness more clearly than allies do.

The maple leaf became a warning in German files, in intercepted memos, in whispered letters home.

And in a flickering command post lamp in December 1943, German officers finally understood something their manuals had not prepared them for:

The Canadians did not fit their categories.

They were not weak.

They were not barbaric.

They were disciplined and adaptive, polite and lethal, predictable in values and unpredictable in timing.

Fighting them was like boxing a shadow that suddenly turns to steel.

By the time German high command admitted it formally—by requiring extra defenders and issuing warnings—the lesson was already written in bodies.

And that is the bitterest kind of learning:

Reality always teaches.

But it charges interest.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.