Why German POWs Begged America to Keep Them After World War II

February 12, 1946. Camp Concordia, Kansas. Silence fell in the wire-mesh hall. 600 German prisoners of war sat motionless, their tin plates untouched and steam rising from their hot food. They refused to eat. Outside, the Kansas wind howled across the prairie. But inside, the only sound was the nervous shuffling of American guards, who had never seen anything like this before.

These weren’t people rebelling against slavery. These were prisoners rebelling against freedom. Hans Schmidt, a writer from Oberg, a former soldier in the Afrika Korps who had spent three years harvesting sweet potatoes with Kansas farmers, stood up slowly. His English had become almost perfect. “We won’t eat,” he announced, his voice carrying through the room.

Until we receive this guarantee, we will not be sent back to Germany. The American camp commandant, Colonel Francis Howard, stood in the doorway. The telegram was crumpled in his fist. It contained orders from Washington. All German infantrymen were to be repatriated immediately, in accordance with the Geneva Convention. He expected relief, perhaps even celebration. Instead, he found himself faced with something the War Department had never expected.

Prisoners who would rather starve than return home. This is the story of a rebellion almost erased from history. A protest not against captivity, but against liberation. And it reveals the truth about World War II that neither the Nazis nor the Allies wanted to reveal. The American paradox of captivity.

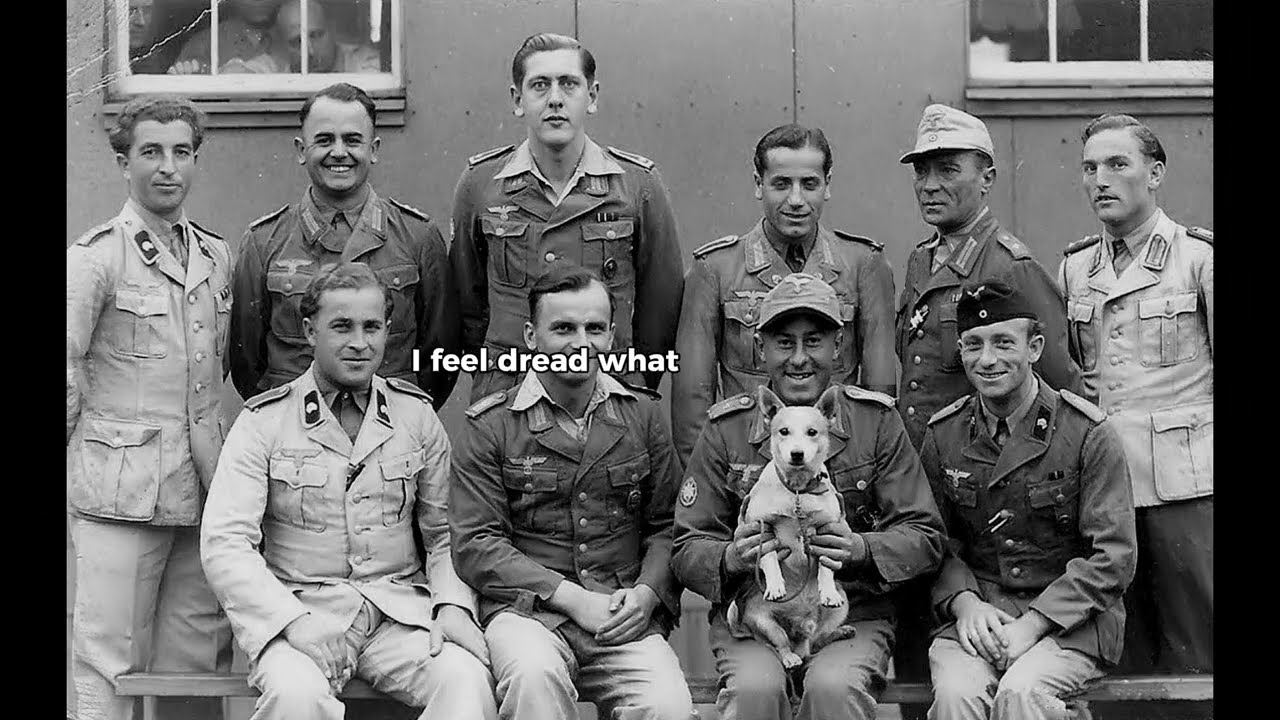

To understand why German soldiers struggled to survive in American POW camps, one must understand what their captivity was really like. And it was nothing like what they expected. When the vagrant Verer Kritzinger was captured in Tunisia in May 1943, his superiors warned him of American cruelty.

Nazi propaganda had convinced him that if captured, he would face torture, starvation, and perhaps even execution. He and his fellow prisoners were transported across the Atlantic in the cramped holds of ships, convinced they were sailing toward destruction. Instead, he found Camp Hearn in Texas. I couldn’t believe my eyes.

Critzinger later wrote in a letter preserved in the National Archives: “American guards served us Coca-Cola. Coca-Cola. We fought for years, eating black bread whenever we could get it. And they gave us this sweet, cold drink as if we were guests, not enemies.” By the end of 1945, the United States held some 425,000 German soldiers in more than 700 camps across the country.

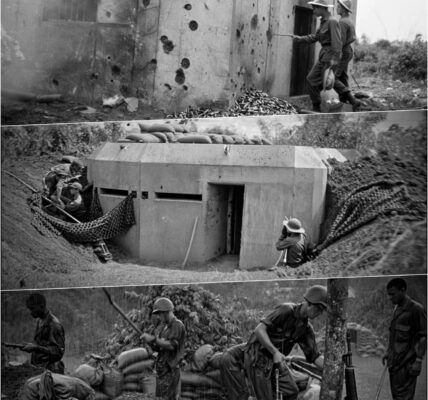

It was the largest Operation P in American history. The camps stretched from Camp Pine in New York to Camp Clarinda in Iowa, from Camp Mexia in Texas to Camp Roert in Idaho. Due to a combination of Geneva Convention requirements, labor shortages in American agriculture, and fundamentally different prison philosophies, these camps operated in a way that shocked German prisoners.

The daily calorie intake for German PS in American camps was 4,000 calories, more than the standard food ration for American civilians and almost twice what German civilians received in bombed-out German cities in 1944. Prisoners received 80 cents a day for working in the camp system. They had access to libraries, sports equipment, and musical instruments.

Many camps had their own newspapers, theaters, and orchestras. At Camp Ko in Mississippi, German social workers published a newspaper, Deruf the Call, which published book reviews, poetry, and philosophical debates. At Camp Maxia in Texas, prisoners built an elaborate miniature German village complete with a working fountain.

At Camp Trinidad, Colorado, they formed a 50-piece symphony orchestra that performed works by Beethoven and Mozart for local residents. Otto Viner, a Marine captured in Normandy in August 1944, lost 18 kilograms (40 pounds) while fighting in France. Within four months at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, he gained the weight back. “But I felt guilty eating so much,” he recalled in a 1983 interview with the U.S. Army Institute of Military History.

From my mother’s letters, I learned that he lived on turnips and potato peels. And I ate roast beef and ice cream. But food is only part of the story. What truly transformed these prisoners was their interaction with ordinary Americans. Crossing the border. The Geneva Convention allowed PS officers to work as long as they weren’t employed in the arms industry.

Faced with American soldiers fighting overseas and a desperate labor shortage crippling agriculture, the U.S. government implemented a massive employment program. Beginning in 1943, German prisoners of war were put to work on farms, hog farms, and logging camps across the country. It was here that barriers truly broke down.

Every morning at Camp Concordia in Kansas, drugs arrived for prisoners who were to be transported to local farms. These weren’t ordinary work assignments. These were cultural exchanges that neither side expected. German PS soldiers ate lunch at farmers’ tables. They learned English from the farmers’ children. They celebrated Thanksgiving and Christmas with American families.

They fell in love with American girls, even though fratinization was officially forbidden. Martha Mueller, the wife of a German-American farmer from Kansas, later recalled: “In 1944, we had three German boys working the wheat harvest. My husband was fighting overseas, and I was feeding German soldiers at the kitchen table.

But these weren’t newsreel monsters. These were homesick boys who showed me photos of their mothers and asked if my husband was safe. The transformation worked both ways. American farmers, who had entered the war with a thirst for revenge, saw Germans as individuals, while German soldiers, raised on propaganda about American degeneracy and Jewish-controlled capitalism, discovered a nation of astonishing abundance and carefree kindness.

By mid-1945, more than 200,000 German PS soldiers were working outside the camps. They picked cotton in Texas, harvested fruit in California, cut trees in Minnesota, and processed sugar in Colorado. They earned money, sent letters home describing what they saw, and began to imagine a future that did not involve returning to a devastated Germany.

Herman Eric Cybold, a Luftwaffe officer held at Camp McCain, Mississippi, wrote in his diary on June 15, 1945: “Today I learned that the war in Europe is over. I expected joy. Instead, I feel fear. What will become of us now? Will we return to the wasteland that Germany has become? My city, Dresden, no longer exists. My parents are dead.

What am I going back to?” This question plagued thousands of German professional soldiers in late 1945, and the U.S. government was not ready to answer it in the way the prisoners had hoped. On January 4, 1946, the War Department issued General Order Number 12. All German professional soldiers were to be repatriated as soon as possible, in accordance with the requirements of the Geneva Convention.

The goal was to return all prisoners to Germany by July 1946. The announcement spread throughout the camp system like an electric shock. At Camp Rustin in Louisiana, the POW camp commandant, Oberl Klaus Mittenorf, immediately noticed the change in atmosphere. The men became quiet. He reported this to American authorities.

There was no singing in the evenings. Many stopped eating properly. A few asked to speak with the camp chaplain, something they had never done before. Statistics painted a grim picture of what awaited them in Germany. By early 1946, 20% of Berlin lay in ruins. In Hamburg, 50% of all residential buildings had been destroyed.

Cologne’s population fell from 750,000 to 40,000. The daily calorie ration in the British occupation zone fell to 40 calories, which meant starvation. In the Soviet zone, the situation was even worse. More terrifying was the uncertainty. Germany was divided into four occupation zones: American, British, French, and Soviet.

Prisoners had no say in which zone they were sent, and stories of Soviet treatment of German POWs were horrific. It is estimated that of the approximately 3 million German soldiers from the PS captured by the Soviets, one million would die in captivity. Even those in western Germany faced bleak prospects. There was no housing, minimal food, and virtually no economy.

Many prisoners knew their families were dead or had been resettled. Some learned that their hometowns were now in Soviet-controlled territory. This meant return was impossible. Then came a deeper realization, one that many Security Service officers struggled to express even to themselves. They had changed. After years in America, they no longer fit into the Germany they had left, and that Germany no longer existed.

In any case, on January 18, 1946, at Camp Concordia in Kansas, a group of prisoners prepared a petition. It was written in neat English and addressed to President Harry Truman. The document, preserved in the National Archives, reads as follows: “We, the undersigned, respectfully request permission to reside in the United States of America.

We worked honestly for American farmers, who will testify to our character. We have learned to respect American democracy and desire to become citizens. Germany is devastated and has nothing for us. We would rather remain prisoners, if necessary, than return to certain starvation and eventual death.

It was signed by 347 men. Similar petitions appeared in camps across the country. At Camp Hearn in Texas, 412 prisoners signed; at Camp Trinidad in Colorado, 289; and at Camp Clark in Missouri, over 500. The answer from Washington was unequivocal. No. The Geneva Convention required repatriation. There were no exceptions. That’s when the resistance began.

Rebellion. The first hunger strike began at Concordia on February 12, 1946, setting the story in motion. Within a week, similar strikes spread to camps in Texas, Oklahoma, and Colorado. American camp commanders were bewildered. Colonel Francis Howard at Concordia struggled with sporadic disciplinary problems, fights between Nazi hardliners and anti-Nazi prisoners, minor work refusals, and escape attempts. But this was different.

It was organized, nonviolent, and emotionally charged. “How do you punish men for refusing to leave prison?” he wrote in a report to the War Department on February 18. “These are not violent people. They don’t destroy property. They simply refuse to cooperate in the fight for their own liberation. Strikes weren’t the only form of resistance.”

At Camp Dermit in Arkansas, prisoners organized coordinated layoffs, working at half the pace they had previously been able to efficiently. Local farmers who had hired them complained to the camp administration. “These boys worked hard for us for two years,” one farmer wrote in a letter to his congressman. “Now you’re starving them again.

Where is the humanity in this?” At Camp Ko, Mississippi, a group of prisoners hired a local lawyer, using the money they earned to explore options for legally remaining in the camp. The lawyer, a young attorney named Robert Hutchinson, took the matter seriously, researching immigration law and writing to the State Department. In his February 1946 letter, he argued that German soldiers who performed essential civilian work should be entitled to special immigration status.

The State Department’s response was swift and negative. Granting such requests would violate international law, undermine the Geneva Convention, and create an impossible precedent. On March 3, the official wrote in response: “The petitions must be denied and the repatriation must proceed, but the detainees’ resistance has become increasingly creative and fierce.

At Camp Hearn in Texas, Unafitzia, Yosef Kramer fell in love with a German-American woman named Anna Schneider, whose family ran a dairy farm where he worked for 18 months. Fraternization was prohibited, but thanks to the relative freedom of assignment, a relationship developed. Kramer proposed marriage, hoping it would provide legal grounds for him to remain.

Anna Schneider applied for a marriage license to marry Kramer. The Army refused. Immigration authorities made it clear that even if they married, Kramer would still be deported, and Anna, as an American citizen, would have to choose between her country and her husband. On March 15, 1946, Kramer attempted suicide by slitting his wrists.

He survived, but the incident sent shockwaves through the entire camp system. Military intelligence began monitoring similar incidents. At Camp Clinton, Mississippi, prisoners stopped singing German songs in the evenings—a tradition that had been a part of camp life for years. Instead, they sang American songs they had learned.

Home on the Range, You Are My Sunshine, even the Star-Spangled Banner. It was a silent, mournful form of protest, a way to declare who they had become. The American guards, many of whom had developed friendships with the prisoners over the years of service, found it difficult to carry out orders, as PFC James Morrison, a guard at Camp Trinidad, wrote in a letter home on March 22.

We’re packing up the guys who worked with us, ate with us, played baseball with us. Some are crying, others look dead inside. I enlisted to fight the Germans, and I did. But they no longer seem like the enemy. The individual stories behind the statistics and strikes were individual, human stories of heartbreaking complexity.

Vera Lent was captured in Salerno, Italy, in September 1943. She had spent almost three years at Camp Swift in Texas, where she worked as a carpenter, when she learned that her hometown of Dresdon had been destroyed in February 1945 by an incendiary bombing. She received confirmation that her entire family was dead. Parents, sister, fiancée—what was he returning to? Lince wrote a letter to the camp chaplain, Father William O’Conor, preserved in the archives of the Catholic Diocese of Austin.

Dated April 3, 1946, it reads: “Father, I believe in God’s plan, but I can’t understand it. I survived the war only to return to a cemetery. Everyone I loved died. The city I knew has fallen to ruins. Here in Texas, I have friends. I have a purpose. The family I work for treats me like a son. Why must I leave life and return to death?” Father O’Conor tried to intervene with the military authorities on Lens’ behalf.

He was politely but firmly told that exceptions were not possible. There was also Helmouth Friedrich, a former teacher from Hamburg who had been captured in France in 1944. At Camp Mexia in Texas, Friedrich taught English to other prisoners and German to interested American guards.

He befriended the camp’s educational officer, Lieutenant Thomas Bradley, bonding over their shared love of literature. When the repatriation order arrived, Bradley wrote a formal letter of recommendation for Friedrich, attesting to his anti-Nazi beliefs and potential value as an American citizen. This man, Bradley wrote, represented the best of Germany.

He believed in democracy, completely rejected Nazi ideology, and would have been an asset to our nation. The letter was folded and forgotten. Friedrich was deported to Germany in May 1946. At Camp Clark in Missouri, a prisoner named Carl Becker became close to a local farming family named Wilson. Wilson’s son died in Normandy.

Initially, they were hostile toward the German prisoners. But over time, working alongside Becca, they discovered something unexpected. Not so much forgiveness as a more complex understanding. When Becca was about to be deported, Mr. Wilson went to the camp and asked to meet with the commandant. “I know this is unusual,” he said, according to a report filed by a camp agitator on April 10.

My son died fighting the Germans, but it wasn’t Carl who killed him. Don’t we see the difference? Carl wants to stay. We want him to stay. He could work on our farm. Why isn’t that possible? The commander had no answer that would satisfy anyone. Forced departure. Despite protests, petitions, and requests, the repatriation went ahead as planned.

The process was systematic and impersonal. Prisoners were loaded onto trains, transported to ports, and placed on passage ships bound for Europe. Most were sent to ports in France and England, and then to camps in occupied Germany, where they awaited trial and final release. At Camp Concordia, the hunger strike ended not because the prisoners changed their minds, but because camp authorities threatened to force-feed the strikers and punish them with isolation before deportation.

Faced with the prospect of spending their final days in America in isolation, most opted for food and time spent with friends. The last transports left the American camps between April and July 1946. At Camp Hearn, residents of surrounding towns came to the fence to say their final goodbyes, an unprecedented event.

Some brought gifts, food for the journey, addresses for letters, and photos. German prisoners lined up for the final roll call, gathered their meager belongings, and marched under armed guard to the waiting trucks. Many wept openly. On May 23, 1946, the last group of prisoners left Concordia Camp. Among them was Hans Schmidt, a man who had gone on hunger strike four months earlier.

As the truck drove away, he looked back at the camp on the Kansas prairie, the land that had been his home longer than anywhere else since the beginning of the war. An American guard who witnessed the departure later recalled, “They looked like men going to execution, not like men coming home.” What happened next? The fates of the repatriated prisoners varied greatly.

Those sent to the American, British, or French zones faced significant hardships, but generally survived. They returned to cities in ruins, with economies in collapse, and a traumatized, divided society. Finding housing was virtually impossible. Food remained scarce until 1948, when the Marshall Plan began providing aid.

For those whose homes were now in the Soviet zone, the situation was far worse. Many were immediately re-arrested and sent to Soviet labor camps. Others disappeared into a police state where their presence in America aroused suspicion. A few prisoners eventually managed to return to America, though it took years. Vera Lens, a carpenter from Dresden, emigrated to the United States in 1952 under the Displaced Persons Act.

He settled in Texas, near Camp Swift, where he had been imprisoned. He worked as a carpenter until his death in 1989. Helmet Friedrich, a teacher, also eventually emigrated. After arriving in 1954, he taught German at a Missouri high school and wrote a memoir in 1976 titled “Prisoner of Peace,” in which he described his conflicted experiences as a German prisoner in America.

Carl Becka managed to return in 1953, thanks to the support of the Wilson family in Missouri. He worked on their farm for 20 years, never married, and was buried in the Wilson family grave after his death in 1973. But these were exceptions. Most never returned. They rebuilt their lives in Germany, carried memories of America with them like ghosts, and rarely spoke of their time as prisoners, fighting to stay in prison.

Joseph Kramer, who attempted suicide rather than leave Anna Schneider, survived and was deported. Anna waited three years and then traveled to Germany in 1949 to find him. They married in Munich, and she stayed with him in Germany, giving up her American citizenship, the opposite of their hope—a forgotten rebellion. Why has this story been so completely forgotten? In part because it complicated the narrative both sides wanted to tell.

For Americans, the story of German social workers who reveled in slavery raised uncomfortable questions about why prisoners lived better lives than many American civilians, especially Black Americans who were still subject to Jim Crow laws. Several camps where Germans were held had better living conditions than nearby neighborhoods inhabited by African Americans, a fact that didn’t go unnoticed.

For Germany, the story was even more disturbing. It suggested that some German soldiers preferred America to their homeland, challenging postwar narratives of widespread German suffering and victimhood. But perhaps most importantly, it was forgotten because it humanized the enemy in a way that didn’t fit neatly into rigid categories.

These weren’t concentration camp guards or SS fanatics. These were ordinary soldiers who, in captivity, discovered that the enemy they had been taught to hate was more humane than the regime they served. Military files on the resistance to repatriation were secret for decades. When they were finally opened, they revealed the scale of the protests.

At least 15,000 German civil servants in more than 30 camps engaged in some form of resistance: hunger strikes, petitions, strikes, legal appeals. None of this changed the outcome. By August 1946, fewer than 5,000 German civil servants remained in the United States, mostly those deemed too ill to travel or facing investigations for war crimes.

By 1947, the camps were empty. The last documented letter from a German prisoner protesting repatriation comes from June 30, 1946, from the Shanks Camp in New York, a staging area for deportations. The prisoner’s name was Hinrich Mueller. He wrote to the camp commandant: “I am not asking to escape punishment for the crimes of my country.

I only ask for permission to stay and build something better than what we destroyed. Isn’t that also justice? His file contains no answer. He was deported to Germany on July 5, 1946. Reflections. The story of the German PS soldiers who fought to remain in America reveals something profound about the nature of ideology, identity, and human bonds.

These men were raised in a totalitarian state, indoctrinated with propaganda about racial superiority and the degeneration of democracy. They fought for Hitler’s vision of Europe. Yet, confronted with the reality of American life—imperfect, not devoid of profound injustices, but fundamentally different from what they had been led to believe—many of them changed.

They changed not through punishment or re-education programs, but through ordinary human contact, through eating at village tables, through working alongside people they had been taught to hate. By discovering that the enemy was not a monster, but a human being. And given the choice between returning to an old, ruined ideology or a new future in a foreign land, thousands chose the latter.

They chose this, knowing they might never see their families again. They chose this, knowing some would brand them traitors. They chose this, guided by the desperate logic of people who saw both sides and understood the difference. The rebellion, of course, failed. The Geneva Convention was unambiguous, and international law mandated repatriation.

The United States couldn’t simply take in hundreds of thousands of former enemy soldiers, no matter how reformed they appeared, but the fact that it happened at all—that German soldiers went on hunger strikes to stay in POW camps, that American farmers begged prisoners to stay in camps, that the line between POW and prisoner could blur so completely—tells us something profound about the human capacity for change and connection, even in the darkest chapters of history.

In February 1946, in a Kansas cafeteria, 600 men refused food because they wanted to remain in prison. It was a rebellion that made no sense in the logic of war, but in the logic of human transformation, it made perfect sense. They came to America as enemies and found something they hadn’t expected: a future.

Being forced to surrender all this was not liberation, but a second enslavement. This time, enslavement by fate, by law, by the inexorable demands of history. And so they resisted, knowing it was futile, because the alternative was accepting that what they had discovered about America, about themselves, about the possibility of becoming something other than what they were, meant nothing in the face of international treaties and political necessity.

They lost their rebellion. But the fact that they fought in it remains a hidden chapter of World War II that deserves to be remembered—not as a curiosity, but as a testament to the human capacity for change and the tragedy of circumstances that prevent its full realization. The camps are gone.

Most were completely destroyed, returned to arable land, converted to other uses, or simply abandoned to their fate. But the archives still hold letters, petitions, reports of hunger strikes, and desperate pleas. Somewhere within these documents lies a truth that neither side wanted to acknowledge: even in war, people are capable of becoming more than their circumstances suggest.

Sometimes even prisoners can be transformed. Sometimes even enemies can become neighbors. Sometimes the hardest prison to escape is the one waiting at home.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.