Why General Patton Ordered His Jeeps to Have “Wire Cutters”

In the dying days of World War II, as the Allies were claiming victory across Europe, a new and terrifying threat emerged. It wasn’t tanks, nor was it airstrikes, but a shadowy, guerilla war waged by Nazi extremists who refused to accept defeat. It was called Operation Werewolf, and its impact was so terrifying that even the most battle-hardened American generals feared it. In the heart of the chaos, General George S. Patton, known for his relentless combat strategies, issued an order that would forever change the way the Allies fought in Germany: every jeep must be equipped with a “wire cutter.” This was no ordinary piece of equipment—it was a deadly innovation born from the most brutal of threats.

The Assassination That Sparked Panic

The story begins in the small city of Aken, Germany, on Palm Sunday, March 25th, 1945. The war was supposed to be over in this part of Germany. The Americans had already captured the city months ago, and the rubble was slowly being cleared. The new mayor, France Oppenhof, had been appointed by the U.S. Army to bring peace to the region. But what should have been a quiet night turned into a nightmare.

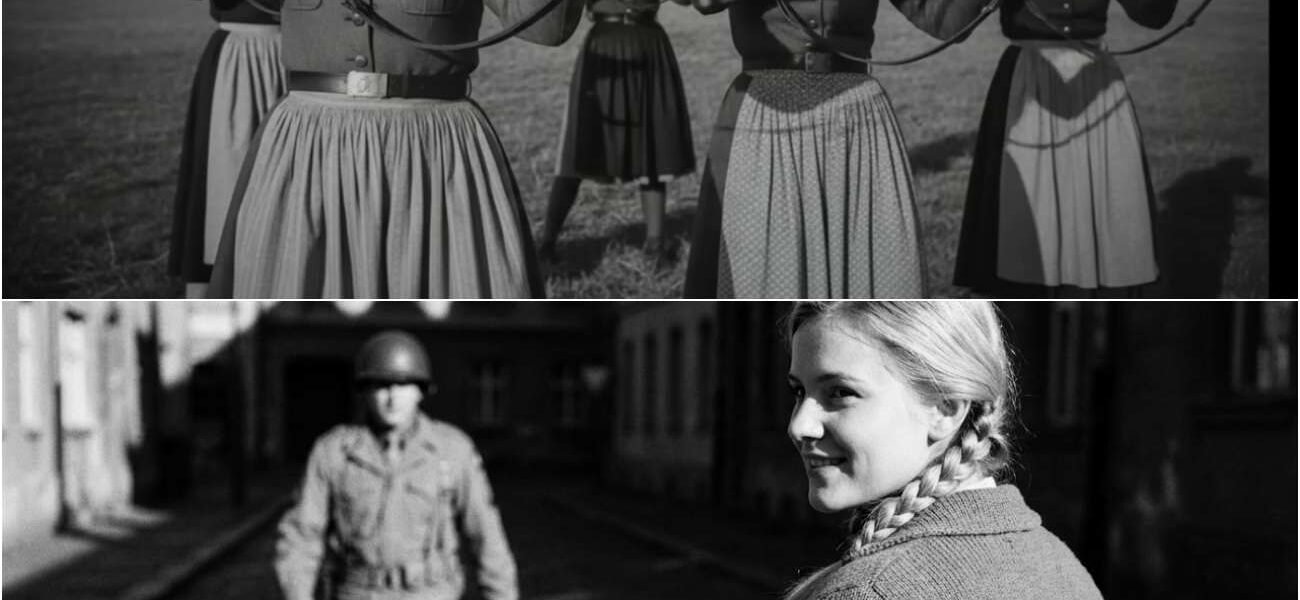

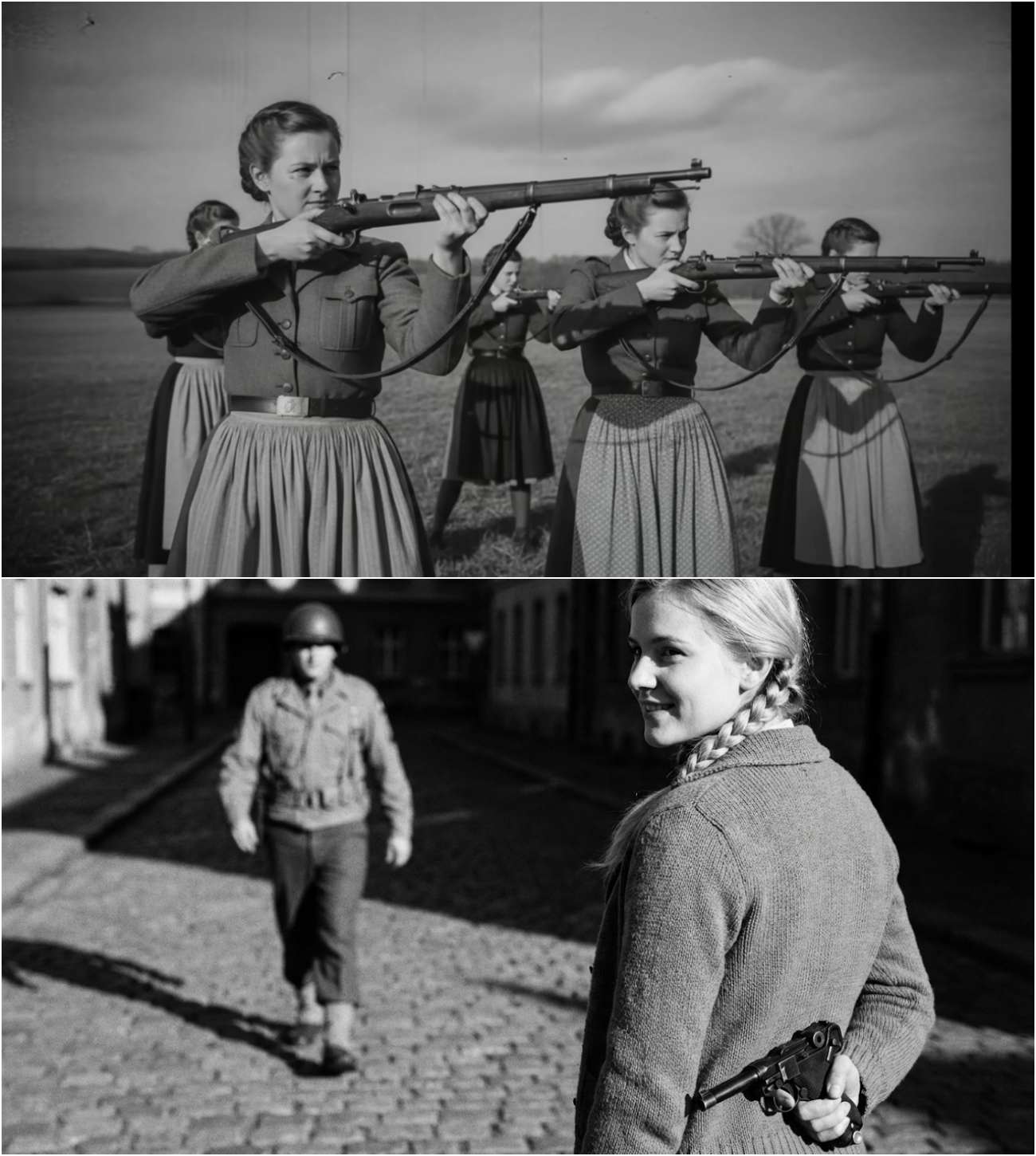

Oppenhof was having dinner with his wife and children, thinking he was safe. He had no reason to suspect that his life was in danger. But outside his house, in the shadows, three figures were creeping through the garden—two men and one woman, all dressed in American flight jackets. The woman, Elsa Hirsch, looked innocent enough, a pretty young girl walking down the street, but she was anything but harmless. She was a member of the League of German Girls, a fanatical Nazi youth organization. She and her two companions were not Americans at all—they were Nazi assassins, part of the secretive Operation Werewolf.

They knocked on Oppenhof’s door, and when he opened it, they greeted him with false smiles. The man in the pilot’s uniform claimed they were American aviators who had crashed and needed help. Oppenhof, ever the kind-hearted man, moved forward to assist them—but then he saw the cold, dead eyes of the woman behind the man. Before he could react, the man pulled out a pistol with a silencer and shot him in the head. Oppenhof collapsed, dead in his own hallway.

The assassins didn’t run—they walked calmly back into the night, their mission complete. It was the first strike of Operation Werewolf, a deadly campaign designed to send a message to every German who had cooperated with the Americans. And it wasn’t just a message to the German people—it was a message to General Dwight D. Eisenhower himself: The war is not over. We are still here.

The Birth of the Werewolves

In late 1944, as the Third Reich was collapsing, Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS, knew that the Nazis had lost the war. But instead of surrendering, he decided to fight a different kind of war—a guerrilla war, one that would be fought from the shadows. He went on national radio and made a chilling declaration. In a voice high-pitched and fanatical, he said, “We will be the werewolves. We will strike from the shadows. We will kill the traitor who works with the enemy. We will kill the American officer in his jeep. We will make their lives a living hell. They will fear the dark.”

The concept was terrifying—werewolves, named after the mythical creature. By day, these Nazis would blend in with the civilian population, but by night, they would become ruthless monsters. Himmler ordered the creation of hidden bunkers in the Black Forest, buried weapons, and recruited the most fanatical boys from the Hitler Youth and the most ruthless girls from the League of German Girls. These recruits were trained in sabotage, silent killing, and stealth tactics.

The Nazis believed they had created an unstoppable force—an army of assassins who would wreak havoc on the American occupiers, striking fear into their hearts.

The Fear Grips America

As the Allies moved deeper into Germany, they began to feel the effects of Himmler’s twisted plan. General Patton, leading the Third Army, was one of the first to hear about the werewolves. His commanders weren’t afraid of tanks—those could be destroyed with artillery. But this new threat was different. How do you fight an enemy who looks like a civilian, who could be a 16-year-old girl with a grenade in her basket? How do you fight an invisible enemy who strikes from the shadows?

Patton knew that the Americans had to adapt to this new form of warfare. Aken, the first major German city to fall to the Allies, became a symbol of the new post-war Germany. The Americans had hoped to restore peace and order there, but instead, they found themselves facing a terror that couldn’t be defeated by traditional means. The murder of Oppenhof sent shockwaves through Allied command. The werewolves were real, and they were hunting the very men who had come to free Germany.

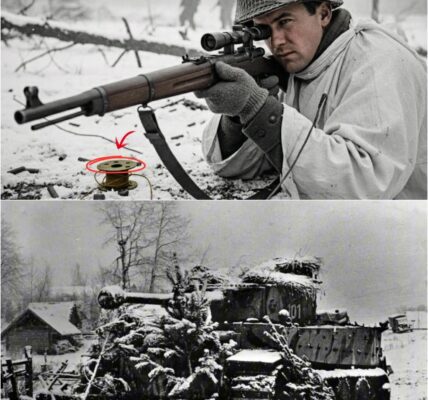

Patton’s Countermeasure: The Jeep Wire Cutter

In response to the growing threat, General Patton took a drastic step. The werewolves had a favorite tactic: decapitation. They would tie a thin, strong wire across a road at neck height. When an American jeep drove by, the wire would slice off the heads of the driver and the officer. This tactic had already claimed several American lives. Patton, known for his fierce pragmatism, knew he had to take action. He ordered his mechanics to weld a steel bar—a wire cutter—onto the front of every jeep in his army. This simple device, which looked like a vertical iron rod sticking up from the jeep’s bumper, saved hundreds of American lives.

But Patton didn’t stop there. He issued a direct order to his troops: If you catch a sniper in civilian clothes, shoot him. If you catch a saboteur, shoot him. We are not playing games with terrorists. The rules of war protect soldiers in uniform. They do not protect spies in civilian clothes. The American military stopped taking chances.

The Failure of the Werewolves

Despite the terror that Operation Werewolf caused, the reality of the werewolves was far less impressive than the Nazis had hoped. Hitler had promised an army of elite guerrillas, but in truth, the werewolves were mostly children—brainwashed boys and girls, armed with Panzerfausts, rocket launchers, and bicycles, told to attack Sherman tanks. One such group of 14-year-old boys attempted to attack an American convoy. The Americans responded with heavy machine gun fire, wiping out the boys in seconds. When the Americans checked the bodies, they found candy in the pockets of the dead soldiers. These were just children, being sacrificed for a lost cause. The Americans were sickened by the sight.

Elsa Hirsch’s Final Fate

Elsa Hirsch, the young girl who had played a key role in the assassination of Oppenhof, managed to escape back into Germany. She thought she was safe, but the Americans never forgot. After the war ended, the U.S. Army’s Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) began hunting down the werewolves. They eventually found Elsa, living a normal life, married with children. She was arrested and put on trial in 1949. The trial became a sensation in Germany—the pretty girl who had been a cold-blooded killer.

But the twist came when the trial was held in a German court. The newly established West German government had control of the courts, and the judges were lenient. Elsa Hirsch was acquitted of murder, though she was found guilty of being a member of a criminal organization. She walked free, her role in the murder of Mayor Oppenhof unpunished.

The Legacy of the Werewolf War

The werewolves, though they had terrorized the American forces for a time, were ultimately defeated not by bullets, but by the overwhelming power of the American military and the kindness of the American occupation. The German people, weary of war, were soon rebuilding their cities, and the terror that had once gripped them was slowly replaced by hope.

General Patton’s strict martial law and his ability to maintain order and discipline among the American forces were key factors in defeating the werewolf threat. By late 1945, the werewolves had vanished—not because they had been killed, but because the German people no longer wanted to fight. The war had been lost, and the American soldiers were now seen as their protectors.

Today, if you look at a vintage World War II jeep, you might notice that strange metal bar welded onto the front bumper. It is a reminder of the time when the enemy wasn’t an army, but a ghost in the woods—a time when even a young girl could be a deadly assassin, and every jeep was a target.

Operation Werewolf may have been a failure, but it left behind a lasting legacy—a reminder that terror can strike at any time, and that the true fight is often not on the battlefield, but in the hearts and minds of those who refuse to surrender.