Why Did the US Army Bolt Logs to Jeeps in WWII?

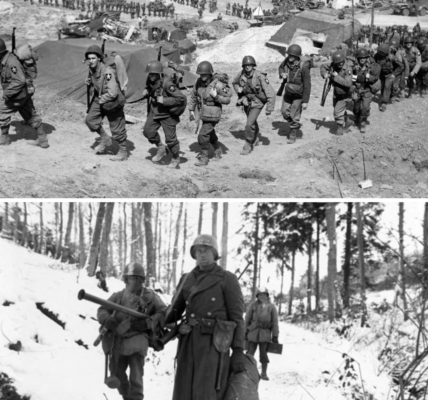

What if I told you that in the autumn of 1944, the greatest threat to the Allied advance toward Germany was not the Tiger Tank, the V2 rocket, or the desperate fanaticism of the Vermacht, but something far more primal, ancient, and unconquerable. Welcome to the Western Front. The date is November 1944. The euphoria of the liberation of Paris has faded, replaced by a cold, gray reality.

The greatest mechanized army the world has ever seen, the United States Army, has ground to a halt. And it wasn’t stopped by steel or gunpowder. It was stopped by water mixed with dirt. They call it General Mud. And right now, General Mud is winning the war. Picture this. A desolate, unpaved supply route somewhere near the border of France and Belgium.

The rain hasn’t stopped for 3 weeks. It’s a cold, piercing rain that soaks through wool uniforms and chills the bones. The road, once a hard-packed dirt track used by farmers, has been churned into a brown sticky soup by thousands of heavy trucks. In the middle of this brown ocean sits a miracle of modern engineering, the Willys MB Jeep.

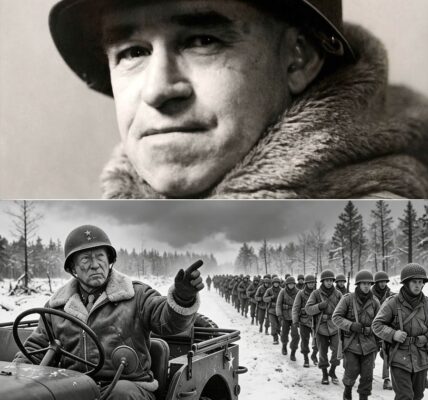

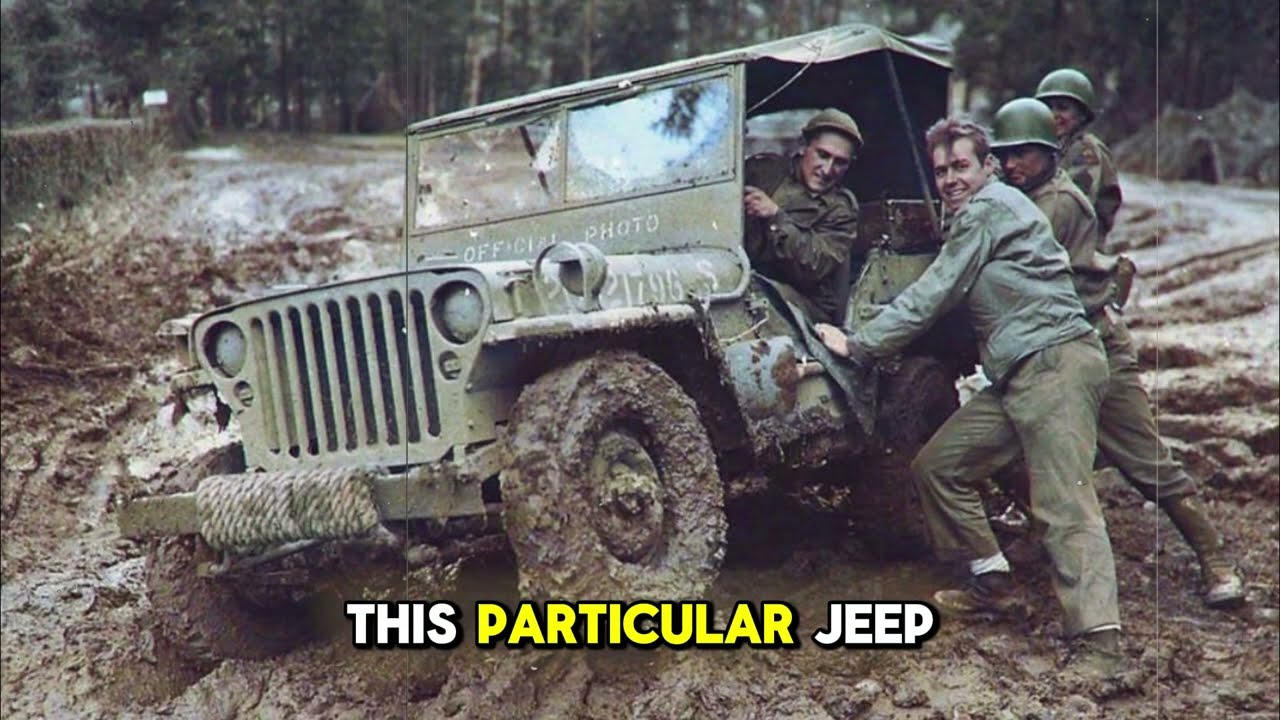

It is the symbol of American mobility. It is agile, it is tough, and it is loved by every GI from Normandy to the Pacific. But right now, this particular Jeep, nicknamed Old Betsy, is helpless. Behind the wheel is Private Tommy Flynn, a 19-year-old kid from Ohio whom everyone calls Sparky. Sparky is sweating despite the freezing rain.

His knuckles are white as he grips the thin steering wheel. He shifts into four-wheel drive, low range, the gears grinding with a metallic protest. He slams his foot on the accelerator. The 60 horsepower goevil engine roars to life. screaming in defiance. The wheels spin furiously, throwing rooster tales of thick black sludge into the air.

But the vehicle doesn’t move forward. It sinks. It settles deeper into the meer like a beast caught in quicksand. The more power Spark he applies, the faster the grave is dug. Standing kneede in the muck next to the vehicle is Sergeant Frank Stone. They call him the hammer because he is hard, unyielding, and brutally direct.

Stone isn’t looking at the spinning wheels. He is looking at his watch and then at the misty horizon to the east. His face is etched with the stress of command. He knows something Sparky doesn’t. He knows that 5 miles up the road at a place simply marked Hill 402 on the map. A platoon of the 1001st Airborne is pinned down.

They are low on mortar rounds. They are low on bandages. And this Jeep is carrying the supplies that will decide whether they live to see tomorrow morning. Stone slams his hand on the hood of the Jeep. The sound is dull and flat against the wet metal. He yells over the roar of the engine, his voice cracking with frustration.

He tells Sparky to ease off, to rock the vehicle, to do anything other than dig them halfway to China. But it is no use. The laws of physics in November 1944 are cruel. Here is the problem. The Jeep was designed for speed and reconnaissance. It is light, which is usually a virtue, but its tires are narrow.

They are designed to cut through loose surface to find traction on the hard ground underneath. But here, in this season of endless rain, there is no hard ground underneath. The mud is bottomless. When the narrow tires spin, they act like circular saws, cutting a trench until the Jeep’s chassis, the frame, and the underbelly slams down onto the surface of the mud.

This is called high centering. Once the belly of the Jeep is resting on the mud, the wheels lose contact with anything solid. They just spin in the liquid. The four-wheel drive system, the pride of Detroit Automotive Engineering, becomes instantly useless. The jeep becomes a one-tonon anchor. Off to the side, watching this struggle with a detached, almost scientific curiosity stands technician fifth grade Otis Campbell. Everyone calls him Greece.

Otis is a man of few words. He was a mechanic in a tractor repair shop in the rust belt before the war. He understands machines better than he understands people. He is smoking a cigarette, shielding the ember from the rain with a cupped hand that is permanently stained with oil. Otis sees what Stone and Sparky are missing.

He isn’t looking at the driver. He is looking at the mud itself. He realizes that they are fighting the wrong battle. They are trying to force the machine to conquer the terrain through brute force, through horsepower and torque. But the terrain is fluid. You cannot punch water. You cannot drive through a liquid with a system designed for solids.

The situation is replicated up and down the line. It is a logistics nightmare. The heavy 2 and 1/2 ton trucks, the deuce and a halfs, have already destroyed the road structure. Their massive weight has pulverized the stone foundations of the European country lanes. The jeeps following in their wake fall into the deep ruts left by the giants.

Convoys that should take 2 hours are taking 2 days. Artillery batteries are silent because shells are stuck in a ditch 10 m back. Ambulances are unable to reach the wounded. The mighty flow of the Allied war machine has been coagulated by rain and dirt. Sergeant Stone wades over to Otis.

The mud makes a sucking sound with every step he takes. He looks at his mechanic. The desperation in his eyes is masked by anger, but it is there. He tells Otis that they are failing. He tells him that the boys on the hill are going to get overrun if they don’t get these crates moving. He asks if there is anything in the manual about this.

Otis takes a long drag of his cigarette and drops it. It hisses as it hits the puddle. He looks at the jeep buried up to its axles. He speaks slowly, his voice calm amidst the chaos. He says that the manual was written by engineers in dry offices in Washington DC. The manual assumes there is a road, but looking around them, the road is gone.

The rules of the road are gone. Otis points out the fundamental flaw. The Jeep is trying to walk on tiptoes across a swamp. What they need is not more power. They don’t need a bigger engine. They don’t need chains on the tires because there is nothing for the chains to bite into. They need to change the nature of the vehicle itself.

They need to stop thinking like a car and start thinking like something else. Stone asks him what he means. Otis walks over to the side of the road where the ruins of an old French barn lie scattered. He picks up a piece of timber, a rough huneed plank of oak darkened by age and rain. He weighs it in his hand. It is heavy, solid, and unremarkable.

But in Otis’ mind, the gears are turning. He is visualizing displacement. He is thinking about surface area. He is thinking about snowshoes. A man sinks in snow because his weight is concentrated on the soles of his boots. Put him on snowshoes and his weight is spread out. He floats. Why can’t a jeep float? The rain intensifies, drumming against the helmets of the men.

Sparky kills the engine. The silence that follows is sudden and heavy, broken only by the sound of the downpour and distant thunder. Or perhaps it is artillery. The jeep sits there, a dead lump of metal. To the casual observer, it is a defeat. But in the eyes of Otis Greece Campbell, it is a blank canvas. The problem has been defined.

The enemy is not the German soldier waiting in the hedro. It is the physics of the earth itself. And to defeat this enemy, they won’t need bullets. They won’t need grenades. They will need a saw, a welding torch, and the kind of desperate American ingenuity that only appears when all the buy the book options have been exhausted.

This is not just a story about a truck. This is a story about the moment when the industrial might of America met the ancient reality of Europe and had to evolve instantly or die. The solution is lying in the rubble of that barn. But will it work? Can you take a precision military machine and bolt lumber to it without destroying it? Sergeant Stone gives Otis a look.

It’s a look that says, “You have until sunset to get us out of this or we walk.” Otis nods. He taps his wrench against his thigh. He calls out to Sparky. Get the toolbox, kid. We’re going to do some carpentry. This is how the legend of the wooden armor begins. Not in a laboratory, but in a ditch in the rain. born of absolute necessity.

Have you ever considered that the most brilliant engineering solutions in history were not born in pristine laboratories with whiteboards and calculators, but in the desperate, filthy corners of a battlefield, sparked by nothing more than fear and a refusal to accept defeat? We move from the open road to the shelter of a bombed out structure nearby.

It used to be a farmhouse, perhaps a stable. Now it is a graveyard of timber and stone. The roof partially collapsed, leaving jagged teeth of wood pointing at the gray sky. Inside, the air is thick with the smell of wet hay, engine oil, and the damp metallic scent of impending failure. This is the temporary command post, the impromptu workshop, and the stage for an argument that will decide the fate of the mission.

Otis Campbell stands before a pile of debris. To anyone else, it is just trash. shattered beams from the barn’s frame, rough huneed planks that once held livestock. But Otis isn’t seeing firewood. He is squinting through the smoke of his cigarette, his mind deconstructing the geometry of the mess in front of him.

He picks up a heavy oak plank about 6 ft long and 10 in wide. It is rough, splintered, and heavy. Sergeant Stone paces behind him, water dripping from the brim of his helmet. The sergeant is a man who deals in certainties. He likes maps, coordinates, and standard operating procedures. What Otis is proposing is none of those things.

It is heresy against the Army Field Manual. Stone demands to know the plan. He reminds Otis that the clock is ticking. Every minute they waste playing with lumber is a minute the boys on Hill 402 are bleeding out without morphine. The pressure in the room is palpable. Young Sparky Flynn sits on an overturned crate, cleaning his glasses, looking back and forth between the two older men like a child watching his parents fight.

He knows that if the jeep doesn’t move, he is going to be walking 20 m with 80 lb of mortar shells strapped to his back. Otis turns to the sergeant. He speaks with the slow, deliberate cadence of a man who knows he is right, but also knows how crazy he sounds. He explains the concept.

He tells Stone to imagine a sled. When you pull a sled over snow or mud, it works because the weight is distributed over a large surface area. It glides. Now, imagine the Jeep right now. All the weight of that vehicle, over 2,000 lb of steel, rubber, and ammunition, is focused on four tiny contact patches where the tires touch the ground.

It is like trying to walk across a frozen lake on stilts. You punch right through. Otis gestures to the jeep parked just outside, its wheels half buried. He says that when the tires dig a trench, the frame of the Jeep hits the mud. The friction of the frame dragging through the sludge is what kills them. It acts like a break. The Jeep is essentially dragging its belly on the ground, and the wheels are just spinning in the soup, unable to find traction.

The solution, Otis argues, is to embrace the belly flop. He proposes bolting the heavy oak planks to the side of the Jeep, running longitudinally between the wheel wells. They won’t touch the ground when the Jeep is on a hard road. They will hang there useless like vestigial wings. But when the jeep enters the deep mud, when the tires start to sink, the wood will make contact.

It will catch the surface of the mud. It will effectively widen the hull of the vehicle. Instead of a narrow steel frame cutting into the earth, the Jeep will have broad flat wooden skids. It will turn the vehicle into a hybrid, half truck, half flatbottomed boat. The wheels will still spin. They will still churn, but the wood will keep the chassis from sinking into the abyss.

It will keep the vehicle floating just high enough for the tires to claw the vehicle forward. Stone looks at the mechanic. He looks at the pile of wood. He looks at the jeep. It is a crude idea. It is ugly. It adds weight to a vehicle that is already struggling. It defies every lesson he learned in motorpool training.

It sounds like the kind of idea a desperate man comes up with right before he does something stupid. But Stone is also a pragmatist. He knows the alternative. The alternative is failure. He looks at Sparky, who is watching with wide, hopeful eyes. He realizes that this isn’t about regulations anymore. It is about survival.

It is about the field expedient, the army term for fixing a problem with whatever junk you have lying around because nobody is coming to save you. Stone takes a deep breath, exhaling a plume of condensation into the cold air. He asks Otis one question. He asks if it will break the axles. Otis shrugs. He admits it might.

The extra weight, the stress on the frame, the drag. It could snap the suspension like a twig. But Otis points out, a Jeep with a broken axle is just as useful as a Jeep stuck in the mud. They are currently at zero. They have nowhere to go but up. There is a moment of silence. The only sound the relentless drumming of the rain on the remaining roof tiles.

It is the sound of the enemy gathering strength. The mud is getting deeper by the second. Stone nods. It is a sharp decisive movement. He gives the order. He tells Otis he has 4 hours, not six. He tells him to turn that jeep into a boat, a sled, or a magic carpet. He doesn’t care. As long as it moves, the decision is made.

The tension in the barn shifts instantly from hesitation to action. This is the American way of war. When the plan fails, you don’t retreat. You improvise. You adapt. You take a saw to a centuries old French barn and you bolt it to a piece of Detroit steel. Otis drops his cigarette and picks up a crowbar. He looks at Sparky.

The grin on his face is the first time he has smiled in weeks. It is the smile of a craftsman who finally gets to work without a manual. He tells the kid to grab the welding torch. They aren’t just fixing a car anymore. They are inventing a monster. As the sparks begin to fly in the dim light of the barn, illuminating the grim faces of the men, we witness the birth of a legend.

It is crude, it is rough, and it is entirely unauthorized. But in the grand chaotic tapestry of the Second World War, it is moments like this, moments of pure, unfiltered ingenuity, that turn the tide. The war of the workshop has begun. How often do we realize that the most profound acts of creation are not born from a desire to build, but from a desperate refusal to die? In the heart of a war that has reduced entire cities to rubble, we find ourselves inside the shell of a French farmhouse, witnessing a reversal of destruction.

Usually, soldiers break things. They blow up bridges. They crater roads. But here, amidst the smell of wet straw and acetylene, three men are trying to make something new. The atmosphere in the barn shifts. It is no longer a shelter. It is a factory. The sound of the rain outside fades into the background, replaced by the rhythmic industrial symphony of metal striking metal.

Otis Campbell takes charge. He is no longer just a technician fifth grade. He is a maestro of the scrapyard. He directs Sparky to the far corner of the barn where the main support beams of the roof have collapsed. They need hardwood. Pine is too soft. It will splinter under the weight of the jeep. They need oak.

Old seasoned oak that has withtood a century of French winters. They find a beam thick as a man’s thigh, dark with age. Together, grunting with effort, they drag it across the dirt floor to the waiting jeep. It is heavy, brutal work. They are cannibalizing history to save the future. Now comes the surgery. You cannot simply glue wood to the side of a steel vehicle.

It requires a fusion of two different worlds, carpentry and metallurgy. Otis lights the welding torch. The hiss of the gas is sharp and angry. A brilliant blue light erupts, casting long, dancing shadows against the stone walls. The light illuminates the sweat on Otis’ face, highlighting the grease stains that give him his nickname.

He is cutting brackets from scrap metal found in the wreckage. Pieces of a gate perhaps, or a broken plowshare. He moves with a surprising delicacy. He welds these makeshift brackets directly onto the steel frame of the Jeep just between the wheel wells. The smell of ozone and burning paint fills the air, stinging the eyes. Sparky watches, mesmerized.

He hands Otis the tools before Otis even asks for them. In this moment, the barrier of rank dissolves. They are just two mechanics trying to solve a puzzle that could kill them if they get it wrong. The precision required is deceptive. If they mount the wood too low, it will drag on the hard sections of the road, sparking and catching on rocks, tearing the suspension apart.

If they mount it too high, it will be useless, passing harmlessly over the mud while the wheels sink. It has to be perfect. It has to sit in the Goldilocks zone, hanging just inches above the ground, waiting to deploy only when the wheels begin to fail. Otis measures the clearance with his thumb and a squinted eye.

He marks the wood with a piece of chalk. Then the saw comes out. The sound of the saw biting into the dry oak echoes through the barn. Sawdust coats their wet uniforms, sticking to the wool like golden snow. Sergeant Stone stands by the door, weapon ready, watching the treeine. He is the guardian of this sanctuary.

Every few minutes, he checks his watch. The hands on the dial are moving too fast. The light outside is beginning to fade, and with the darkness comes the enemy. But he doesn’t rush them. He knows that a rushed job is a failed job. He watches Otis bolt the massive planks onto the welded brackets. The sound of the ratchet wrench click click click is a ticking clock of a different kind.

It is the sound of progress. Finally, the noise stops. The torch is extinguished. The saw is silent. Otis steps back, wiping his hands on a rag that is dirtier than his hands. They look at their creation. It is not pretty. In fact, it is hideous. The sleek functional lines of the Willy’s Jeep are gone, replaced by these bulky, primitive wooden protrusions.

It looks like a chariot from a forgotten age, or a bizarre hybrid of a tank in a log cabin. It is a Frankenstein monster of metal and timber. Sparky walks around the vehicle. He runs a gloved hand along the rough grain of the wood. It feels solid. It feels like armor. For the first time in weeks, the fear in his gut is replaced by curiosity.

He looks at Otis. Otis nods, a microscopic gesture of approval. He kicks the tire, then kicks the wood. It doesn’t budge. The vehicle is wider now, heavier and ungainainely, but it looks ready for a fight. Stone turns from the door. He looks at the modified machine. He doesn’t see a mess. He sees a weapon against the elements. He sees a chance.

“Load up,” Stone says, his voice low and steady. “Let’s see if this wood floats.” The engine coughs, then roars to life, echoing louder in the enclosed space. The exhaust blows a cloud of blue smoke into the damp air. As Sparky shifts into gear and the Jeep rolls toward the open barn doors, toward the relentless rain and the waiting mud, they are no longer just driving a car.

They are piloting an experiment, and the laboratory is the battlefield. Is the true test of a man’s courage found in how he faces a bullet? Or is it found in that breathless second when he trusts his life to a desperate idea that has never been tried before? The barn doors swing open, revealing a world that has been washed of all color.

It is a landscape of gray rain, black trees, and brown earth. The convoy is waiting, a line of steel serpents dormant in the gloom. Men are huddled under ponchos, smoking soggy cigarettes, staring at the road ahead with the vacant look of soldiers who have nowhere to go. When Sparky pulls the modified Jeep out into the light, heads turn.

A few soldiers point. Someone laughs. It is a harsh barking laugh that sounds out of place, and you can’t blame them. The vehicle looks absurd with those thick, rough huned timbers bolted to its flanks. It resembles a bathtub trying to be a tank. It is an ugly duckling in a fleet of war machines.

Sergeant Stone ignores the stairs. He climbs into the passenger seat, his Thompson submachine gun resting across his knees. Otis hops into the back, squeezed in among the crates of ammunition. He doesn’t look at the other soldiers. He is listening. He is tuning his ears to the sound of the engine, waiting for the first sign of strain. All right, kid.

Stone growls, pointing through the rain streaked windshield. Straight up the gut. Don’t stop for anything. Sparky nods. His hands are shaking just a little. He grips the wheel until his knuckles turn white. Ahead of them lies the kill zone, a 100yard stretch of road where the mud is so deep it has swallowed trucks whole.

This is where the advance died this morning. Sparky shifts into second gear. He revs the engine. The Jeep lurches forward. They pick up speed. 10 m an hour. 20. The wind whips the rain into their faces, stinging like needles. The road is slick but manageable at first. Then they hit the soup. The transition is violent. One moment they are driving, the next they are drowning.

The front wheels slam into the deep sludge, sending a wave of brown water crashing over the hood. The Jeep shutters violently. The momentum dies instantly. This is the moment where every other Jeep failed. This is the moment where gravity usually wins. Sparky gasps, instinctively flooring the accelerator.

The wheels spin wildly, screaming as they lose traction. The vehicle begins to sink. You can feel the sickening drop as the tires dig their own graves. But then something different happens. Thud. A dull, heavy vibration runs through the frame of the car. It isn’t the metallic screech of the steel chassis hitting rock.

It is the solid, muted sound of wood hitting earth. The oak planks, bolted to the sides, slam down onto the surface of the mud. For a split second, time seems to suspend. The engine is roaring. The wheels are churning liquid, but the jeep doesn’t sink any further. It hangs there, suspended by Otis’s carpentry. The wood acts like a ski, spreading the weight of the vehicle across the surface of the meer.

It’s holding, Otis yells from the back, his voice cracking with disbelief. The Jeep is no longer driving in the traditional sense. It is surfing. The spinning wheels act like paddle steamers, churning the mud to propel the vehicle forward, while the wooden skids keep the belly from dragging. It is a chaotic, bucking, violent ride. Mud flies everywhere, coating the men in a thick layer of slime.

The jeep slides sideways, drifting like a rally car in slow motion. Sparky fights the wheel, wrestling the machine to keep it straight. They pass a stranded deuce and a half truck. The driver of the truck, a burly corporal, stands on the running board, his mouth hanging open. He watches as this wooden monstrosity, crawls past him, defying the laws of physics that have trapped him there for hours.

Inside the jeep, the noise is deafening. The engine is redlinining. The wood scrapes and groans against the earth, a sound like a ship running a ground, but they are moving. Inch by agonizing inch, they are cutting through the impossible. Stone is laughing. It is a manic wild sound. He pounds the dashboard with his fist. Go, go, go, he screams.

They reach the end of the mud pit. The front tires find purchase on a patch of gravel. The tires bite. The Jeep lunges forward, launching itself out of the sludge and back onto solid ground. Sparky slams on the brakes. The Jeep skids to a halt, steam rising from the hood and the wheel wells. Silence returns, save for the panting of the men and the steady rhythm of the rain.

They are alive. They are through. Sparky slumps over the steering wheel, laughing hysterically. Stone wipes a handful of mud from his face, looking back at the track they just conquered. He looks at the two long, flat furrows left in the mud. The tracks of a sled where there should have been tire ruts.

Otis leans forward from the back seat. He doesn’t smile. He just lights a fresh cigarette, his hands steady now. He pats the rough splintered wood of the side plank. Told you, Otis whispers. snowshoes. They have proven the concept, but the war isn’t over. The road to hill 4002 is still long, and the wood is already soaked and heavy.

They have won the battle against the mud, but the cost of that victory is about to become clear. Because in war, every solution creates a new problem. Have you ever noticed that in the history of warfare, no matter how advanced the machine becomes, the final mile always belongs to the muscle and sweat of the infantrymen? We often look at photographs of World War II and see the tanks, the planes, and the trucks.

And we think of it as a war of engines. But look closer. Look at the famous image that inspired this journey. You see the wooden armored jeep. Yes. But what else do you see? You see men. You see shoulders leaning into steel. You see boots digging into the sludge. You see the undeniable truth that technology does not replace the soldier.

It merely gives him a fighting chance. As Sparky pilots the modified jeep deeper into the forest, the adrenaline of the initial success begins to fade, replaced by the grinding reality of the mission. The laws of physics are stubborn. The wood has prevented the jeep from sinking into the abyss, but it has not turned the road into a highway.

The mud is still sticky. The incline is steep, and the engine is getting hot. They reach a section of the trail that is less like a road and more like a river of molasses. The Jeep slows, the wheels spin, the wood catches the surface, keeping them afloat. But the forward momentum is dying. The engine whines in protest, the temperature gauge creeping into the red.

They are stuck again, but this time it is different. They aren’t buried. They are just stalled. Sergeant Stone doesn’t panic this time. He kicks open the door and jumps out into the muck. He waves to a group of infantrymen sheltering near the treeine. the very men they are sent to resupply.

“Give us a hand,” Stone bellows. The soldiers rush forward, and here is where the genius of the design reveals its second purpose. Usually, pushing a jeep is a nightmare. There is nowhere to grab. The fenders are slippery steel. The bumpers are too low. But now, now there are massive oak beams running the length of the vehicle.

They are at hip height. They are solid. They are perfect handles. The soldiers line up along the sides of the jeep. They grab the wood. Heave!” Stone yells, and the vehicle moves. This is the crucial difference. Without the wood, the Jeep would be bellied out, stuck by suction. It would take a tank to pull it free.

But because the wood is acting as a ski, keeping the chassis above the suction zone, the friction is manageable. The soldiers aren’t trying to lift a 2,000lb dead weight. They are simply sliding a sled. Sparky feathers the gas. The soldiers push. The jeep groans and slides forward, clawing its way up the hill.

It is a symphony of man and machine working in perfect harmony. The wood has bridged the gap between the impossible and the possible. It turned a hopeless situation into a problem that could be solved with a little elbow grease. But as they reach the summit and the supplies are unloaded, Otis Campbell walks around the vehicle.

He places a hand on the wood. It is no longer the dry hard oak they bolted on in the barn. It is spongy. It is water logged. Otis does the mental math. Dry oak is heavy. Wet oak is twice as heavy. He looks at the suspension springs of the Jeep. They are compressed almost to the limit. The vehicle is sagging.

The added weight of the armor plus the mud caked into every crevice between the wood and the steel is killing the fuel economy and torturing the transmission. Otis realizes the trade-off. This is not a permanent evolution. It is a bandage. If they keep this wood on for a month, the moisture trapped between the lumber and the bodywork will rust the steel frame to dust.

The extra weight will eventually snap an axle or blow the engine. It is a crude solution. It is ugly. It is destructive in the long run. But then Otis looks at the soldiers on the hill. They are opening the crates of ammunition. They are passing around the rations. They are alive and they are armed because this strange wooden hybrid made it up the hill when nothing else could.

Stone walks over to Otis lighting a cigarette. He follows the mechanic’s gaze to the sagging springs. “She’s heavy,” Otis says quietly. “She won’t last forever like this.” Stone takes a drag and looks at the men on the line. “She doesn’t have to last forever, Greece. She just had to last until today.” In that moment, we understand the true nature of the innovation.

It wasn’t about building a perfect machine. It was about buying time. It was about sacrificing the longevity of the equipment to save the lives of the men. The wooden armor was never meant to be a new standard. It was a desperate answer to a desperate question valid only for this specific season of hell.

As the sun begins to set, casting long shadows over the muddy tracks. The jeep sits there steaming and scarred. It is a tool that has done its job. But as we will see, even the most temporary tools can leave a permanent legacy. The rains of November eventually turned into the snows of December. The soft swallowing mud of the French countryside hardened into ground as frantic and brittle as iron.

The battle of the Bulge was on the horizon, bringing with it a new set of horrors. But for the muddy lanes of the supply route, the specific nightmare of the bog was over. In the motorpool, the atmosphere was quiet. The urgency of the previous weeks had settled into a grim routine. Otis Campbell stood next to the Jeep, his breath visible in the freezing air.

In his hand was the same wrench he had used to bolt the oak planks to the frame just a month earlier. Now he was taking them off. The wood was battered. It was gouged by rocks, splintered by shrapnel, and stained dark with the oil and mud of a 100 miles of hell. As Otis loosened the bolts, the heavy timber fell to the frozen ground with a hollow thud.

Sparky Flynn watched him. He looked at the Jeep, stripping down to its original factory standard silhouette. It looked naked without its wooden armor. It looked vulnerable again. He asked Otis why they couldn’t keep it. After all, it had saved them. Otis picked up one of the planks. It was heavy, waterlogged, and rotting from the inside out.

He explained that everything has a season. The wood had done its job. It had carried them when the wheels could not. But now on the frozen roads, the extra weight would only slow them down. To survive the next chapter of the war, they had to adapt again. They had to shed the weight of the past to move fast enough for the future.

That evening, the squad gathered around a fire drum. They didn’t use coal. They used the oak planks. The wood that had served as their armor against the mud now served as their shield against the cold. As the flames consumed the battered timber, Sergeant Stone stared into the fire. He realized that the true weapon wasn’t the wood. It wasn’t the jeep.

It wasn’t even the rifle on his shoulder. The true weapon was the mind of a mechanic who refused to accept that stock was a permanent condition. 80 years have passed since that fire burned out. The Jeep Willies has become an icon, a collector’s item polished and paraded in museums. But look closely at the modern world.

Look at the overland vehicles equipped with traction boards and sand ladders strapped to their sides. Look at the engineers who solve problems in space using duct tape and cardboard. Look at every person who fixes a broken situation with nothing but a rusty tool and a refusal to quit. They are all spiritual descendants of Otis Campbell and his wooden jeep.

The story of the wooden warriors is not just a footnote in a history book about military logistics. It is a parable for us today. We all face our own versions of General Mud. We all face moments where the road ahead disappears, where the standard operating procedure fails, and where the wheels start to spin helplessly. In those moments, we often look for a savior. We wait for the cavalry.

We wait for the weather to change. But this story tells us that sometimes the answer isn’t coming from above. Sometimes the answer is lying in the rubble pile next to us, waiting for someone brave enough to pick it up and build a way out. Those men are gone now. The barn is gone. The mud has long since been paved over by modern highways.

But the lesson remains etched in the grain of history. It reminds us that while technology changes, the human spirit does not. It reminds us that there is no such thing as a dead end, only a lack of imagination. As the smoke from that fire in 1944 drifted up into the winter sky, it carried with it a simple, profound truth that echoes down the decades to us right now.

In the end, it wasn’t the wood that got them home. It was the will to keep moving.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.