When They Put a P-39 Nose on a Tiny Boat — Japanese Called Them “Devil Boats”

The Devil Boats: The 37mm Cannon

A New Kind of Weapon

At 11:30 PM on October 21st, 1942, First Lieutenant Robert Lynch sat at the helm of PT48, guiding his boat through the calm, overcast waters near Guadalcanal. The mission was simple, yet the stakes were high: intercept and destroy Japanese barges transporting troops and supplies. PT boats, known for their speed and maneuverability, had been ineffective against the heavily armored Dhatsu barges. The torpedoes, while devastating to larger vessels, had little impact on these smaller, shallow-draft targets. The crew was running out of options.

Lynch had heard the stories: the Japanese “Tokyo Express” ran barge convoys every night, with light tanks, machine guns, and heavily armored barges. The American torpedoes weren’t a match for these small, elusive vessels. With each failed mission, the pressure on PT boat crews mounted. The enemy seemed unbeatable. But Lynch was not someone to back down. He was a high school history teacher before the war, and now he found himself fighting a new kind of battle—a battle of resourcefulness, determination, and, most importantly, innovation.

The solution came from an unlikely source: the wrecked P-39 Airacobras scattered across Henderson Field. These aircraft, which had seen their fair share of combat and crashes, still held one key asset—their 37mm M4 automatic cannons. These powerful weapons, designed for aircraft, could shred light armor and destroy barges with pinpoint accuracy. The only problem? There were no official protocols or installations for mounting them on PT boats. But that wouldn’t stop Lynch.

The Modification Begins

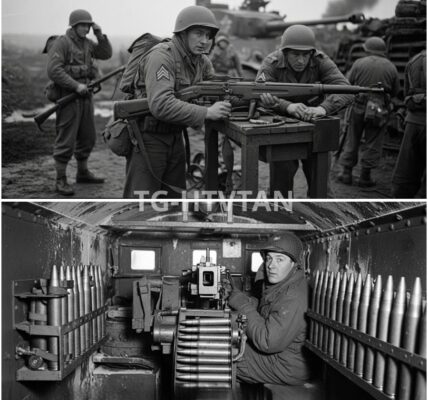

Lynch’s team at Henderson Field worked fast. They salvaged the aircraft cannons, disassembling them from the wrecks of the downed P-39s. The task wasn’t easy. Aircraft cannons weren’t designed for shipboard use, and the PT boats weren’t made to house such heavy weapons. But necessity breeds invention. The crew worked into the night, welding and cutting, adapting the mounts for PT48. It was a makeshift solution, but it was a solution.

By the early hours of October 21st, the cannon was ready for installation. There were no standard procedures, no manuals. Just a burning desire to change the tide of war. The pedestal mounts, while crude, were effective enough to hold the 37mm cannon in place. The mechanics knew the risks—they had no guarantee the mount would hold under the recoil of the rapid-fire weapon, or that it would even fire accurately. But there was no time for second-guessing. If it worked, it would change everything.

The First Engagement

As PT48 moved toward the Japanese supply barges that evening, the crew was anxious. The 37mm cannon had never been tested in combat. The fear was palpable. Would it fire? Would it hit the target? And would it stay attached to the boat? Lynch commanded the crew with quiet resolve, but even he was uncertain of the outcome. The barges, loaded with soldiers and supplies, continued to move down the narrow waterways.

At 11:55 PM, the radar operator signaled the presence of the enemy. Four Japanese barges, moving at 8 knots, were on a direct path. Lynch gave the order: “Prepare for fire.” The PT boat approached, the ocean calm, the distant silhouettes of the barges becoming clearer in the darkness. As they closed in, the crew readied themselves. Gunner’s Mate Second Class Harold Mitchell, who had volunteered to operate the cannon, sat behind it, gripping the ammunition.

When the target came into range, Mitchell fired the first shot. The M4 cannon roared to life, its muzzle flash lighting up the night sky. The recoil sent the weapon jerking backward, but it held steady. The first round hit the lead barge squarely on the waterline. The explosion was immediate—steel plate armor shattered like paper, and the diesel engine inside the barge erupted in flames. The fire spread quickly, and men began to leap into the water, abandoning the sinking vessel.

Mitchell, unfazed by the explosion, kept his finger on the trigger. The M4 fired again, emptying the first magazine in 12 seconds. The barge was already burning, but the second in line was still moving. Mitchell reloaded the cannon quickly, firing another 30 rounds at the second barge. The results were devastating. The second barge exploded in a massive fireball, its ammunition cooking off, sending debris flying through the air. The remaining barges scattered in disarray.

The Psychological Impact

The attack was successful. Two barges were destroyed, and a third was disabled. But what came next was even more significant than the tactical victory. The psychological impact on the Japanese forces was immense. The barges, once immune to torpedo attacks, had been destroyed by an unexpected weapon—a weapon mounted on an American PT boat. The Japanese crews, used to the relative safety of their barges, now feared what they had once considered invincible. The Japanese called the PT boats “demon boats” with “aircraft guns”—and they were right.

The success of PT48’s engagement with the barges sent shockwaves through the Pacific theater. No longer were PT boats limited to reconnaissance and torpedo runs. They now had the capability to destroy entire supply lines with direct fire. The psychological impact on the Japanese forces was profound. They had underestimated the Americans and the ingenuity of their soldiers. Now, they had to adapt.

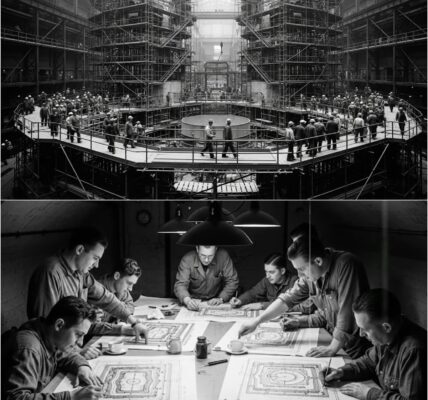

The Spread of Innovation

By October 23rd, 1942, four more PT boats in Squadron 3 had been outfitted with salvaged M4 cannons. The modification, once seen as a desperate measure, had now proven itself effective in combat. The PT boats, once known for their torpedo attacks, had evolved into heavily armed gunboats. The cannons allowed them to close the distance, engage targets more effectively, and destroy barges before they could escape.

However, the modification was not without its challenges. The cannons, while effective, were prone to wear and tear. The recoil systems had to be adjusted, and the ammunition supply was inconsistent. But the benefits outweighed the drawbacks. PT boat crews had learned to work around the limitations. They had become better gunners, better tacticians, and more determined fighters. The use of the 37mm cannon had fundamentally altered the way PT boats operated.

The Battle for Guadalcanal

The transformation of PT boats didn’t stop there. The addition of the 37mm cannon allowed the boats to continue their mission of disrupting Japanese supply lines. In the waters surrounding Guadalcanal, where barge traffic was vital to the Japanese war effort, PT boats with these new weapons were wreaking havoc. The boats’ ability to engage at closer ranges and destroy barges meant that the Japanese could no longer rely on their supply lines to support their forces on the island.

As the war in the Pacific progressed, the cannons proved their worth again and again. By January 1943, PT boats equipped with the M4 cannon had destroyed 87 Japanese vessels, including 63 barges, and disrupted the enemy’s ability to maintain its supply chain. The addition of the M4 cannon had increased the boats’ effectiveness and reduced the risks to American crews.

A Legacy of Innovation

The success of the M4 cannon modification didn’t go unnoticed. It became standard issue for PT boats in the Pacific and beyond. The weapon’s success demonstrated the value of field modifications and the importance of adapting to the enemy’s tactics. But it wasn’t just about the weapon itself—it was about the creativity and resourcefulness of the men who had made it work.

In the years that followed, the lessons learned from this modification shaped military innovation. The ability to adapt, to improvise, and to use available resources to solve real problems was critical to success. And it was these lessons that carried the PT boats through the war.

The Men Who Made It Happen

The men behind the PT boats’ transformation—Lynch, Kugan, Frey, and Mitchell—became legends in their own right. Lynch, who commanded PT48 and led the charge to install the M4 cannon, was recognized for his innovation and bravery. Kugan, the aircraft armorer who had worked tirelessly to modify the cannons, became a key figure in maintaining and improving the PT boat’s weaponry. Frey, the machinist who designed the original mounts, laid the groundwork for the weapon’s success. Mitchell, the gunner’s mate who fired the first shots from the cannon, became a symbol of the courage and determination that defined the PT boat crews.

Though their roles in the war were vital, they returned to civilian life after the conflict ended. Lynch worked as an electrical engineer in Philadelphia, while Kugan remained in the Air Force, retiring as a master sergeant in 1962. Mitchell went on to work for Boeing in Seattle, and Frey continued working at a shipyard after the war. But the legacy of their work lived on. The weapon they had salvaged from wrecked aircraft became an integral part of the PT boat’s arsenal, changing the course of naval warfare in the Pacific.

The Final Victory

By the end of the war, PT boats equipped with the M4 cannon had destroyed over 800 Japanese vessels, including barges, patrol boats, and landing craft. The effectiveness of the weapon had been proven across multiple theaters, from the Solomon Islands to the Philippines to the Mediterranean. The success of the modification showed that innovation in the field could change the course of a war.

The PT boat crews, once considered an underdog in the naval warfare of the Pacific, had proven their worth. The addition of the M4 cannon gave them a fighting chance, and they used it to devastating effect. The weapon that had started as a desperate improvisation had become a key factor in the success of the PT boats. And it all started with a group of men who refused to give up, who believed in their ability to adapt and innovate, even in the face of overwhelming odds.

As the war came to a close, the lessons learned from the PT boats’ transformation were passed down. The men who had fought with these weapons became a part of history, their legacy continuing to inspire future generations of soldiers. The M4 cannon, once an improvised weapon, had changed the face of naval warfare. And the men who had made it possible would never be forgotten.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.