- Homepage

- Uncategorized

- When 5 German Panthers Attacked — This Sherman Gunner’s 5 Shots Destroyed Them All. NU

When 5 German Panthers Attacked — This Sherman Gunner’s 5 Shots Destroyed Them All. NU

When 5 German Panthers Attacked — This Sherman Gunner’s 5 Shots Destroyed Them All

At 2:27 p.m. on June 14, 1944, the hedgerows outside a small Norman village trembled with distant engine noise.

Sergeant Gordon Harris crouched inside his Sherman Firefly, sweat trickling down his spine despite the cool air trapped beneath the turret roof. Through the narrow slit of his periscope, five dark shapes emerged from the haze—German Panther tanks, advancing across open fields with deliberate confidence.

They were eight hundred meters away.

Harris was thirty-one years old.

He had been in Normandy for eight days.

He had destroyed zero tanks.

Around him lay the wreckage of the past week. Burned-out Shermans. Twisted tracks. Blackened hulls abandoned in the fields. The British 7th Armoured Division had already lost forty-two tanks since landing in France. The reason was simple and brutal.

Panthers ruled the battlefield.

German tank crews had learned quickly. The standard Sherman’s 75mm gun could not penetrate a Panther’s frontal armor beyond three hundred meters. The Germans knew it. They attacked head-on, confident that Allied shells would bounce harmlessly away while their own long-barreled guns punched through with ease.

But Harris did not command a standard Sherman.

He commanded a Firefly—an American-built tank armed with a British gun that almost never existed.

Eighteen months earlier, British officials had tried to kill the Firefly project before it was born.

Mounting the massive 17-pounder anti-tank gun inside an American Sherman turret was declared impossible. The gun was too long. The recoil too violent. The turret too cramped. Britain, the Ministry insisted, would soon have better tanks of its own.

Two officers ignored those orders.

They cut metal where they were told not to. They moved radios outside the turret. Removed crew positions. Redesigned recoil systems. They turned a reliable American tank into something dangerous—awkward, controversial, and lethal.

By D-Day, only 342 Fireflies existed.

One per troop.

Too few.

And instantly recognizable.

German commanders issued orders within days: “Kill the Fireflies first.”

Harris knew that order well.

Four days earlier, his tank commander had been killed by a Panther shell that punched straight through the turret. The man died before the smoke cleared. Harris had taken command without ceremony, without time to doubt himself.

Now, five Panthers were coming straight toward the village his infantry was defending.

Three standard Shermans hid uselessly behind stone buildings.

Only the Firefly could stop them.

Harris positioned his tank behind a low stone wall on the village edge. Hull down. Only the turret exposed. It was the best cover available, but it would not last long. The Firefly’s longer barrel protruded far beyond the wall, impossible to conceal completely.

Beside him sat Trooper Alec McKillip, the gunner.

Twenty-four years old.

Scottish.

Calm hands.

Sharp eyes.

McKillip had fired only seven shots in combat before today.

None at a tank.

The Panthers advanced in a loose line, their crews confident, methodical. The lead tank’s commander stood half-exposed in his cupola, scanning for threats. He saw nothing.

Range dropped.

Six hundred meters.

At this distance, the Firefly’s 17-pounder could punch through the Panther’s frontal armor like paper.

If the shot was true.

Harris leaned closer to McKillip and spoke quietly.

“Take your time. Make it count.”

The Panther commander dropped into his turret.

Hatches slammed shut.

McKillip centered his sight on the narrow band where the Panther’s glacis met the turret ring—the weakest point on the tank’s front. He adjusted for distance, for movement, for the slight crosswind rippling the hedges.

At 2:30 p.m., he fired.

The 17-pounder erupted.

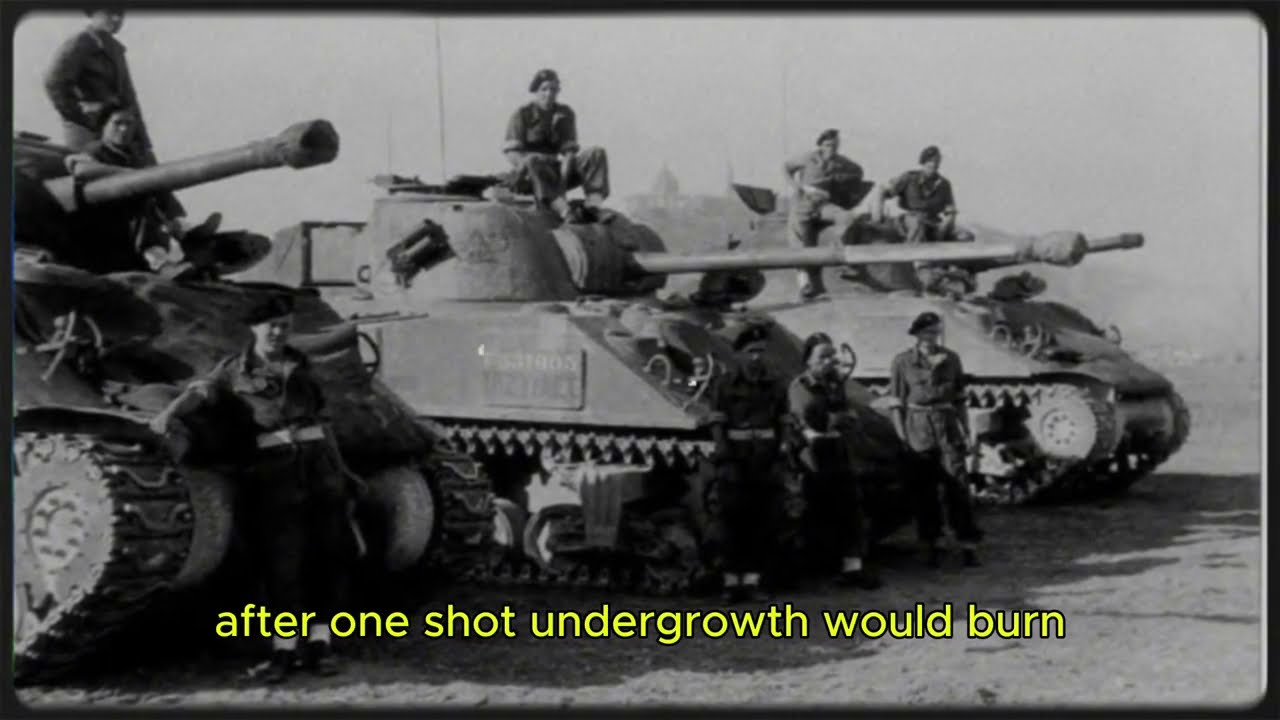

The entire Firefly recoiled backward six inches. A blinding flash turned the world white. The hedge in front of them ignited instantly, leaves and branches bursting into flame.

When Harris could see again, the lead Panther was dead.

The shell had penetrated cleanly, killing the crew without explosion or fire. The tank rolled forward a few meters and stopped, silent.

Four Panthers remained.

They reacted instantly.

Professional crews.

No panic.

Two Panthers veered left. Two to the right. The fifth reversed hard, searching for cover. Smoke from the burning hedge marked the Firefly’s position clearly.

Harris knew they had seconds before return fire.

McKillip traversed right, tracking a Panther turning broadside.

He fired again.

The shell struck the side armor near the suspension. The Panther detonated violently, its turret lifted into the air like a toy and slammed down upside-down.

Two Panthers destroyed in forty seconds.

The remaining three fired together.

Shells slammed into the stone wall, showering the Firefly with debris. One round screamed overhead close enough to be felt through the steel.

Harris ordered the driver to reverse.

The Firefly backed behind a barn just as the Germans corrected their aim. Wood exploded. The barn partially collapsed. Dust filled the air.

They were exposed.

McKillip chose the flanking Panther.

Range: four hundred fifty meters.

The German tank charged forward, presenting its frontal armor. Harder shot. Smaller margin.

McKillip fired.

The round punched through the lower glacis and shattered the transmission. The Panther lurched and stopped. Its crew bailed out, scrambling for cover.

Three Panthers down.

Two remained.

And they were close.

The fourth Panther fired again, smashing through the barn remains. The Firefly had nowhere left to hide.

McKillip had three seconds.

He fired first.

The shell crossed four hundred meters in less than a second and struck the Panther’s gun mantlet—the thickest armor on the tank.

It penetrated anyway.

The turret exploded free, landing thirty feet away.

Four Panthers destroyed.

The fifth Panther paused.

Its commander understood.

Four tanks lost in under two minutes.

He began to reverse toward the tree line.

Harris considered letting it go.

Then the Panther stopped.

Turned.

Presented its side.

The German commander was not retreating.

He was setting up a duel.

Six hundred meters apart, both tanks went hull down.

Both gunners aimed.

Both commanders waited.

The Panther fired first.

The shell missed by three feet.

McKillip fired while the German gun recoiled.

The 17-pounder round struck the turret face, penetrated, and ended the fight.

Five Panthers destroyed in six minutes.

Silence returned to the field.

Three standard Shermans emerged cautiously from behind buildings. Their crews stared in disbelief. They had not fired a single shot.

British infantry advanced, weapons ready, securing the burning hulks.

Harris climbed out of the turret and looked across the battlefield.

Five German tanks.

Five perfect hits.

No losses.

Reports spread fast.

Intelligence officers arrived. Measurements were taken. Penetration angles recorded. The engagement was documented and circulated across Normandy within twenty-four hours.

The conclusion was unmistakable.

The Firefly worked.

The weapon that bureaucrats had tried to cancel three times had just defeated Germany’s best tanks, crewed by veterans from the Eastern Front.

But the report carried a warning as well.

The Firefly’s muzzle flash revealed its position instantly. Its long gun made maneuvering difficult in villages. German crews were already adapting.

Victory today meant danger tomorrow.

Harris and McKillip kept fighting.

Their Firefly destroyed nine more German tanks over the next two months. It took eleven hits and survived them all. When it was finally knocked out in September, the crew escaped unharmed.

After the war, Harris returned home and worked quietly as a mechanic. McKillip became a schoolteacher. Neither wrote memoirs. Neither sought fame.

But their six minutes outside that Norman village mattered.

Between D-Day and VE Day, Sherman Fireflies destroyed more German heavy tanks than any other Allied vehicle. They were American machines transformed by British ingenuity and Allied necessity—a symbol of how innovation and courage could overcome superior armor.

Sometimes, the weapon nobody wants becomes the one that saves lives.

And sometimes, victory belongs not to the biggest tank—

but to the crew who knows exactly where to aim.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.