What Made the Australian SAS Survival Diet a Nightmare for US Special Forces?

The jungle measured men in pounds.

Not the clean, honest pounds of a scale in a gym back home, but the ugly kind—pounds that bit into collarbones, that turned sweat into salt burns, that made your knees argue with every step. In Vietnam, you could die from a bullet, sure. But you could also die because you were too heavy to move when you needed to, too loud when you needed to vanish, too slow when the jungle demanded you be a shadow.

The first time I saw the Australians pack for a long-range patrol, I thought they were either reckless or insane.

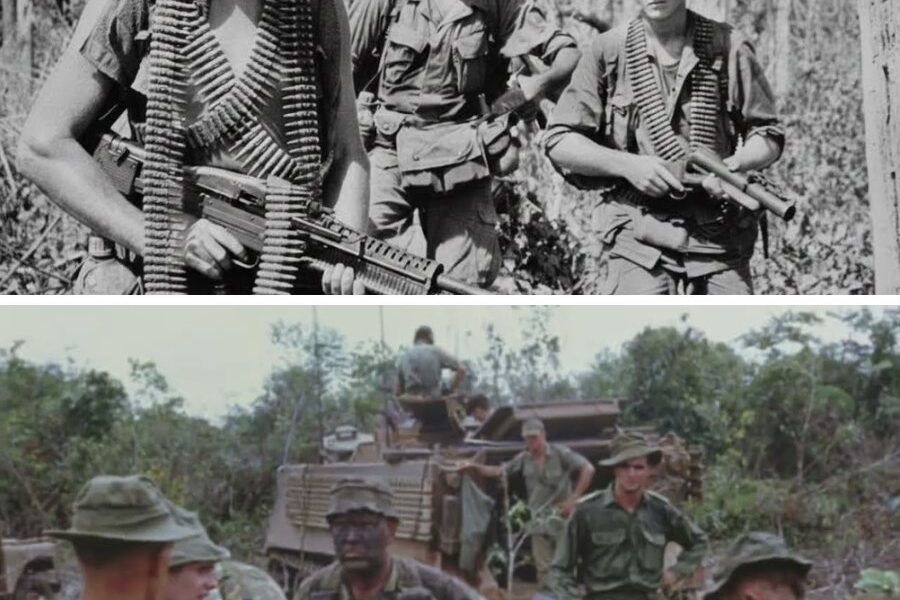

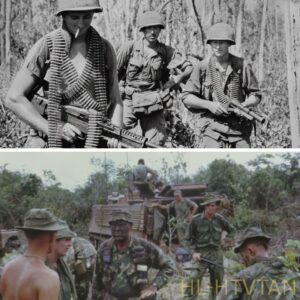

We were standing on the edge of a clearing at Nui Dat, the air already thick with the kind of heat that felt personal. The Americans around me wore their gear like portable warehouses—bandoliers, radios, canteens, spare canteens, extra socks, ponchos, poncho liners, spare boots if they could manage it, and the real heart of it all: food. Cans. Sealed packets. The promise that somewhere behind us there was a system big enough to feed an army.

A typical American infantryman on a long patrol carried what looked like a mountain. Eighty pounds was considered normal. A hundred wasn’t rare. You learned to walk with your spine bent, like a man permanently bowing to gravity.

Then the Australian SAS troopers walked past us with packs that looked… wrong.

Compact. Tight. Riding high on their backs. No clanking cans. No bulging sacks of rations. Their silhouettes were lean in a way that made them look faster even standing still, like they had springs under their boots. They didn’t sag.

They moved like they could run if they needed to.

A sergeant beside me muttered, half impressed, half suspicious. “Where the hell’s their chow?”

One of the Australians, a wiry guy with a sun-browned face and eyes that didn’t waste motion, heard him.

He smiled without humor. “In the jungle,” he said, and kept walking.

That was my introduction to the “snake eaters.”

They didn’t call themselves that, at least not proudly. It was a nickname that floated through the task force like gossip—part revulsion, part awe. The Americans said it the way you say something you can’t quite decide if you respect or fear. Like: Those blokes aren’t right. Those blokes are something else.

I was an American, attached as an observer—“liaison,” the paperwork called it—to learn from them, report back, maybe borrow tactics that would save lives. I’d done patrols with U.S. units. I knew the comfort of an MRE. I knew the reassurance of a canteen sloshing. I knew the way packaged food let you believe you were still connected to civilization.

And now I was about to walk into the deep bush with men who treated civilization like dead weight.

They planned like accountants of misery.

Every item was weighed. Literally. A small hanging scale, the kind you’d use for fish, swung from a branch while they clipped gear to it and watched the needle. If it didn’t justify its existence, it stayed behind. If it didn’t contribute to killing, moving, or staying alive, it was treated like a luxury.

Food was the first luxury to die.

They carried a few emergency blocks—hard slabs that looked like compressed oats and sugar, meant to keep you upright, not satisfied. A few packets of dehydrated soup—thin powder that could become warmth in a tin cup without requiring a roaring fire. And the strangest sacred item of all: a tiny tin of Vegemite.

When I first saw it, I thought it was a joke. Back home, a jar of yeast paste would have been something you hid in a pantry and forgot. Out here, it was treated like a tactical asset.

One of the troopers—his mates called him Mick—held up the tin like it was ammo.

“B vitamins,” he said, as if explaining something obvious to a child. “Keeps the engine running when the fuel’s low.”

“You’re going out for two weeks with… that?” I asked, because my brain refused to accept what my eyes were seeing.

Mick shrugged. “Three, four days,” he said. “That’s what we carry. After that, it’s the bush.”

“The bush,” I repeated. “You mean you… forage?”

The Australians exchanged looks like I’d asked whether they breathed air.

“Mate,” Mick said quietly, “you carry food, you carry noise. You carry rubbish. You carry your own trail. You want to be found, carry cans.”

One of the older troopers—an older face, younger eyes—leaned in and spoke like he was giving a lesson he’d had to learn the hard way.

“We don’t have resupply,” he said. “We’re deep. Ten days, fourteen days. The jungle’s not optional. You either learn it, or it kills you.”

They weren’t romantic about it. They didn’t talk about “becoming one with nature.” They talked like men discussing physics.

Weight made you slow.

Slow made you loud.

Loud made you dead.

That was the equation.

I’d trained with Green Berets. I’d seen survival training. It was serious, yes, but it always felt like a supplement—an extra tool in the kit. For the Australians, it wasn’t extra. It was foundational. Their entire way of fighting depended on being invisible, and invisibility depended on being light.

Watching them pack felt like watching men choose hunger deliberately.

They weren’t starving themselves as a stunt. They were designing a gap—an empty space in their logistics—and then trusting their knowledge to fill it. It was terrifying and brilliant.

On the day we stepped off, the heat hit like a wet hand. The jungle swallowed sound. The air smelled of rot and green things crushed under boots.

We moved single file, spacing out, each man a separate shadow. Their pace was steady, almost deceptively easy, like they weren’t fighting their packs at all. My pack—despite being “lightened” by American standards—still felt like a boulder. It creaked when I shifted. A strap squealed once and Mick turned his head toward me so fast it felt like being caught stealing.

“Quiet,” he mouthed.

I nodded, throat dry.

By the first hour, I understood the difference between “carrying weight” and “being worn by weight.”

The Americans lumbered. The Australians glided.

They didn’t stomp. They didn’t crash through brush. They placed their feet like they were walking on glass. They didn’t talk unless they had to. Signals were hand movements, finger taps, a tilt of the head. Even breathing felt regulated.

At midday, we stopped in a place that looked like nothing—a cluster of trees and vines indistinguishable from any other. The men vanished into it. One moment they were there; the next they were part of the jungle.

Mick motioned me down beside him and handed me a small chunk of an energy block. It tasted like sugar and sawdust. My stomach wanted more immediately, but there was no more.

“That’s lunch?” I whispered.

Mick gave me a look that wasn’t cruel, just matter-of-fact. “That’s not lunch,” he whispered back. “That’s insurance.”

We drank water in sips so small it felt insulting. My American instincts screamed at me to drink deep, to fill up while I could. The Australians sipped like men rationing time.

Then we moved again.

On the third day, my brain started doing something strange.

It sharpened.

Hunger does that. It peels away the fat of thought. It makes small sounds feel larger. It makes the world vivid, almost painful. I could hear the click of a beetle’s wings. I could hear my own heartbeat when we lay still.

We had reached a place near a trail—an enemy route, according to intelligence. The Australians called it a “lie-up,” a final position where you became part of the landscape and waited.

We waited for hours.

Then for days.

Seventy-two hours in near stillness, watching through gaps in leaves. Sipping water. Chewing tiny portions of the emergency blocks.

No fires. No cans. No packaging tearing open like a signal flare. No litter. Nothing.

At night, I could hear American patrols in my mind—the clink of a spoon, the crinkle of plastic, the whispered jokes that made men feel less alone. Here, alone was the point.

On the fourth day, the emergency rations were almost gone.

On the fifth day, they were gone.

And the Australians did what they had promised:

They ate the jungle.

The first time I saw it, it was so simple I almost missed it.

We stopped beside a fallen log, rotten and spongy. Mick crouched and peeled back bark with a knife, slow and precise, like he was opening a letter.

Underneath, the wood was alive with pale, fat grubs—larvae, slick and pulsing faintly as they flexed. They looked like something you’d find in a nightmare.

My stomach turned.

Mick plucked one between two fingers like it was a grape.

“Jungle prawns,” he whispered.

I stared, horrified.

He glanced at me. “Protein,” he said simply.

Then he ate it.

Not dramatically. Not with bravado. With the same calm he used when checking his rifle.

Another trooper split the log further and gathered a handful into a cloth. They didn’t take everything—only what they needed. Even foraging was disciplined. No unnecessary disturbance. No obvious sign left behind.

They didn’t light a fire the way an American might. They heated a rock in a tiny pit buried under leaf litter, using embers so small they looked like dying eyes. Then they roasted the grubs quickly, just enough to make them firm.

No smoke plume. No smell that carried far. Just a faint heat and a quiet meal.

I tried to watch without gagging. One of the Australians noticed my expression and gave me a look that wasn’t mocking, just knowing.

“Don’t think about it,” he whispered. “Think about what it buys you.”

“What it buys you,” Mick said quietly, “is the ability to stay here and not die.”

I couldn’t eat the grubs that first day. My body rebelled. I chewed another piece of my ration block and felt the hollow ache in my stomach intensify.

That night, lying motionless in the dark, listening to enemy voices drift past like ghosts, I realized how stupid comfort could be.

Comfort makes you careless.

Comfort makes you noisy.

Comfort makes you easy to find.

By the sixth day, hunger erodes pride.

When Mick offered me a roasted grub, I took it.

It tasted… like nothing, really. Slightly nutty. Slightly oily. It wasn’t delicious. It wasn’t horrific either. It was fuel.

And the moment it slid down my throat, I understood something that made me ashamed of my earlier disgust.

The Australians weren’t being “gross.”

They were being alive.

Insects weren’t the only thing the jungle offered.

Ants—big ones, acidic and sharp—were eaten like a bitter snack. Termite mounds were quietly raided for pale insects that could be scooped and swallowed quickly. Berries were tested cautiously. Tubers were dug from soft earth.

Everything was done with knowledge, not desperation.

That knowledge had a history.

One night, while we lay hidden and the jungle dripped around us, one of the older troopers—Jack, they called him—told me quietly about Borneo.

“Before Vietnam,” he whispered, “we learned in Malaya, in Borneo. Jungle’s the enemy if you treat it like one. But if you learn it… it feeds you.”

He spoke of Iban trackers—men who could read a footprint like a sentence. Men who knew which vines held water and which ones held death. Men who taught Australians what Western manuals never could.

“Textbook says ‘find a stream,’” Jack murmured. “Stream gets you killed. Enemy drinks there. Tracks there. Booby traps there.”

He tapped a vine beside us gently. “This is water,” he whispered. “Not that river.”

He didn’t explain it like a lesson. He didn’t need to. The Australians had absorbed indigenous knowledge the way you absorb a language when your life depends on it.

Water was the bigger issue than food.

Hunger could be tolerated for days. Dehydration could end you in hours, especially in that humid heat that sucked moisture out of you without you realizing.

A gallon of water weighed too much to carry for two weeks.

So they harvested water from the jungle like it was part of the terrain.

They cut vines and drank clear liquid that tasted faintly of wood. They collected dew with cloth in the early morning, wringing it into cups like it was treasure. They dug seep holes beside muddy sources, letting water filter through earth before treating it.

They didn’t splash in streams. They didn’t refill canteens in open places. They drank like ghosts.

Every method had one thing in common:

Silence.

Silence was their weapon.

The first time we saw the enemy up close, I understood the value of silence in a way no briefing could teach.

We were lying in a shallow depression, covered in leaf litter, faces smeared with mud and green. My nose filled with the smell of earth and sweat. My body ached from stillness.

Then voices drifted through the trees.

Vietnamese. Low. Close.

I couldn’t see them at first. Then shapes moved between trunks—three, four men, rifles slung, walking with the easy confidence of people who thought they owned the jungle.

They passed within twenty meters.

Twenty.

Close enough that I could see the shape of a scar on one man’s cheek. Close enough that I could smell cigarette smoke.

My heart hammered so hard I thought they would hear it.

Mick’s hand was on my sleeve, a gentle pressure that said: Don’t move.

I didn’t move.

One of the enemy soldiers paused, peering into the brush. His eyes scanned. For a second, they looked directly through the space where Mick’s face was hidden.

Mick didn’t blink.

The enemy soldier shifted, spat, and kept walking.

When they were gone, I realized my hands were shaking.

Mick leaned close and whispered, “If you had a can of stew in your pack, mate… if you had to open it right now, you’d be dead.”

I swallowed hard.

That night, I understood why they were willing to eat grubs.

Because the alternative wasn’t just hunger.

It was exposure.

Exposure meant annihilation.

In the jungle, food wasn’t comfort.

Food was camouflage.

A few days later, we found snakes.

Not in a dramatic “sudden strike” way, but in that constant presence the jungle has—life sliding through leaves, dangerous things moving nearby, the environment reminding you that you are not the apex predator here unless you choose to be.

We were near a water source when Jack froze, hand up.

Everyone stopped instantly. Not a whisper. Not a shuffle. Stillness like a switch.

Jack pointed.

A snake lay coiled near the base of a tree, motionless, its body patterned to blend into shadow.

My stomach tightened. Back home, snakes were fear. In Vietnam, snakes were fear with consequences.

To the Australians, it was also dinner.

The trooper closest to it moved with slow precision. No panic. No sudden gestures. He pinned the snake with a stick, hands steady, then severed its head quickly.

The body writhed with reflex, muscle moving even without the brain.

I had to clench my jaw to keep from making a sound.

The Australians worked without drama. They stripped the skin, cut the meat, cooked it on hot stones over embers hidden beneath leaves.

No smoke plume. No campfire glow.

Just quiet meat.

When I tried to imagine an American patrol doing this, I couldn’t. We would have shot it, loud and sudden, and broadcast our position for a hundred meters.

The Australians didn’t fire a shot.

They didn’t just eat the snake. They used it as proof of dominance over the jungle.

They weren’t afraid of the thing other men feared.

They turned fear into calories.

At first, the idea sickened me.

Then hunger and respect made it normal.

When Mick handed me a piece of snake meat, I hesitated only a moment.

It was chewy, mild, almost like chicken if you stopped thinking too hard.

Mick watched my face, then gave a faint grin.

“Congratulations,” he whispered. “You’re one of us now.”

I almost smiled.

Almost.

Because the next day, we got close enough to an enemy position that I could hear laughter from a hidden camp. I could smell cooking smoke—faint, distant, drifting through the jungle like a confession.

The Australians stayed silent, motionless, observing through scopes and narrow gaps in foliage. They counted men, tracked movement, took notes in tiny waterproof notebooks.

Their mission wasn’t to fight. It was to know.

War, to them, was information.

They radioed in sparingly, brief transmissions timed and coded. Radios were heavy, batteries heavier. Even communication had to justify its weight.

We stayed in that area for two days, watching, mapping, learning.

At one point, an American instinct rose in me—we should do something. We should strike. We should call in air support. We should make noise.

But the Australians didn’t measure success by explosions.

They measured it by absence.

If they left and the enemy never knew they’d been there, that was victory.

When we finally moved out, we left nothing behind.

No tins. No wrappers. No cigarette butts. No obvious latrine marks.

Waste was either buried carefully or carried out.

Even the places where we’d lain for days looked untouched when we left, leaves arranged, ground smoothed like the jungle had never been disturbed.

Their footprint wasn’t small.

It was almost zero.

That was the part that truly stunned me.

The Americans, even the best, left traces. Plastic. Foil. A dropped matchbook. A crushed can. Something.

The Australians treated every trace like a betrayal.

They didn’t just hide from the enemy’s eyes.

They hid from his instincts.

Enemy trackers—trained to read disturbed leaves and broken twigs—had nothing to follow.

You can’t track a ghost.

The longer we stayed out, the more my body changed.

My stomach stopped expecting fullness. Hunger became a dull companion rather than a crisis. My senses sharpened. I began noticing small things: a bird call that didn’t belong, a subtle shift in wind that carried human scent, a patch of ground that looked too recently disturbed.

The Australians were like that all the time.

Controlled hunger had honed them into something sharp.

It wasn’t romantic. It wasn’t fun. It was discipline.

And discipline was their survival.

When extraction finally came, it was almost anticlimactic.

We moved to a pickup point, timed precisely. A helicopter came in low and fast, rotors chopping air, noise suddenly enormous after days of silence. For a moment, being loud felt obscene.

We loaded quickly, packs light enough to lift without struggle. The Australians moved with the same economy they’d shown in the jungle, no wasted motion.

As the helicopter lifted, I looked down at the sea of green swallowing everything, and I felt something strange: gratitude.

Not for the war. Not for the suffering. But for the lesson.

Because I had entered the jungle believing logistics was strength.

I left understanding that excess can be weakness.

Back at base, an American major asked me what I’d learned.

I wanted to say a thousand things. About weight and silence and hunger. About grubs and snakes and how men can become predators when they stop insisting the world feed them comfort.

Instead, I said the simplest truth.

“They’re lighter,” I said. “And because they’re lighter, they’re invisible.”

The major frowned. “What do you mean lighter?”

I hesitated.

How do you explain that the Australians had replaced the weight of food with the weight of knowledge?

How do you explain that their advantage wasn’t gear—it was intimacy with the environment?

I said, “They don’t carry what we carry. They carry skill.”

The major grunted like he didn’t fully believe it.

Maybe he didn’t want to.

Because believing it meant questioning the American philosophy: abundance, supply lines, the comfort of knowing you could be fed anywhere.

The Australians had proven something uncomfortable:

A soldier supported by wealth can still be vulnerable if the wealth makes him slow.

A soldier supported by knowledge can be lethal even when hungry.

In the weeks after that patrol, stories spread through the base like all stories do.

Americans whispered about the Australians eating snakes, about them cracking open logs for grubs, about them drinking water from vines. Some told it like horror. Some told it like awe.

I understood why.

Watching an Australian calmly roast a snake over hidden embers while knowing the enemy could be fifty meters away doesn’t just demonstrate survival.

It demonstrates psychological dominance.

It says: The jungle does not frighten me. I will not be broken by discomfort.

It’s hard to explain how much that matters in a place designed to break you.

Months later, when I was back with American units, I noticed our noise more. The crinkle of packaging. The clink of cans. The way we moved like we assumed the jungle belonged to us. We were still good—brave, capable, determined.

But we were louder than we needed to be.

And loudness in the jungle is a confession.

I started carrying less. I started teaching younger guys to tape down loose gear, to minimize noise, to treat trash like evidence. I started telling them that hunger isn’t the worst enemy.

The worst enemy is being seen when you need to be nothing.

I didn’t tell them to eat grubs. That wasn’t my place. That wasn’t my culture. But I told them the principle behind it:

If you can reduce your footprint, you reduce your risk.

If you can carry knowledge instead of weight, you move like a predator instead of prey.

Years later, long after Vietnam became a memory people argued about on television, I still thought about the Australians.

Not their guns. Not their kills. Not their medals.

Their silence.

The way they could lie still for days, living on almost nothing, because their mission demanded it.

The way they treated hunger like a tool, not a tragedy.

The way they turned the jungle from an enemy into a supplier.

That’s why the nickname stuck.

“Snake eaters.”

It wasn’t just about what they ate.

It was about what they were willing to become to survive.

They stripped themselves down to essentials and trusted their minds to fill the rest.

And that, more than any weapon, was their advantage.

In war, we like to believe the strongest force wins.

The most guns. The biggest bombs. The heaviest supplies.

But the jungle doesn’t care about your supply chain.

The jungle cares about physics.

Weight.

Noise.

Trace.

And the men who understood that—who treated weight as an enemy and knowledge as armor—became the closest thing to ghosts the war ever produced.

They didn’t win with sweeping battles.

They won by not being there when the enemy looked.

By being light enough to disappear.

By accepting deprivation not as suffering, but as strategy.

And if there was one enduring lesson in all of it, it wasn’t about grubs or snakes or Vegemite.

It was this:

Sometimes the fiercest weapon isn’t what you carry.

It’s what you’re willing to leave behind.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.