“What Is This Food?” Inside a Texas POW Camp, German Women Meet American Corned Beef—and a Meal That Changes How They See the Enemy. NU

“What Is This Food?” Inside a Texas POW Camp, German Women Meet American Corned Beef—and a Meal That Changes How They See the Enemy

In the spring of 1945, the wind in west Texas didn’t just blow—it prowled. It came in low over the scrub and the cattle fences, nosed under the mess-hall doors, and carried the smell of dust into everything you tried to keep clean. It rattled the flagpole rope like nervous fingers and made the barbed wire sing a thin, metallic note that sounded too much like laughter if you listened at the wrong hour.

Private First Class Helen “Lennie” Carter listened anyway.

She was twenty-three, from Wichita Falls, and had joined the Women’s Army Corps because there were only so many times you could watch a war on a movie screen and still pretend it wasn’t real. They’d trained her on typewriters, filing systems, and the kind of cheerful discipline that looked good in recruitment posters. Then they’d shipped her to Camp Coyote Flats—an unromantic patch of land where the Army kept prisoners who were very far from home.

Her job was officially “clerical support.” In practice, it meant she did whatever needed doing and didn’t ask too many questions about why. On mornings like this, it meant she stood in the doorway of the mess hall with a clipboard, watching the cooks set out trays like they were loading ammunition: beans, bread, coffee, and the newest item that had come in with the last supply truck—stacked cans with a plain label and a promise the Army always loved.

CORNED BEEF.

The cooks called it “bully beef,” though nobody could agree where the bully part came from. It arrived in squat tins, packed so tight you could practically hear it groan when you opened it. When you sliced it, it held the shape of the can like it was proud of it.

The German prisoners had never seen anything like it.

Which, if you’d asked Lennie, seemed nearly impossible. Germans had food. Germans had sausage and rye and those neat little pastries that looked like they belonged in a bakery window instead of a battlefield. But the war had been grinding the old world down to scraps, and the women arriving that morning didn’t look like anyone who’d had pastries lately.

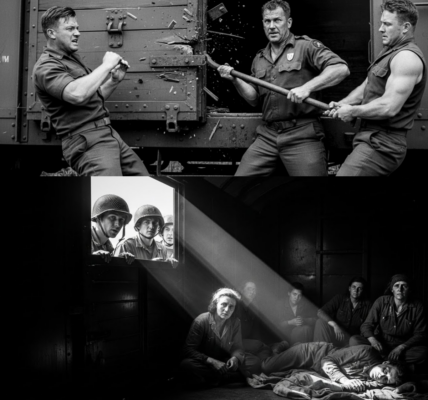

They came in a column, guarded by MPs with rifles slung like reminders. Forty-one of them, all women, mostly in their late teens and twenties, wearing mismatched uniforms and issued coats that didn’t quite fit. Their hair was pinned back or cut short. Their faces had that pale, careful set of people who had learned not to waste expression.

A new kind of POW detail, Lennie had been told—women captured as the Reich collapsed and units surrendered in bunches, women who’d served as clerks, radio operators, nurses, auxiliaries. No front-line SS myth, no goose-stepping parade. Just tired people with tired eyes, transported halfway across the world so the war could keep them somewhere safe while it finished itself.

They filed into the mess hall under the sign that said EAT HEARTY and the smell of coffee and hot metal.

A few glanced around like they expected a trick. Others kept their eyes down, staring at boots and floorboards. One woman, taller than most, paused just long enough to take in the room—windows, benches, American posters on the wall, a framed photo of President Roosevelt that someone had not yet had the heart or time to replace. She met Lennie’s gaze without flinching, then moved on.

Lennie checked her clipboard. Liesel Krämer, the manifest read, because Lennie had been nosy enough to peek at the paperwork earlier. Radio operator. Captured near Bremen. Spoke “some English.”

That would be useful. Because the first time the Germans saw the corned beef, it was going to be a circus.

The cooks slid the tins open with a key and dumped the contents into pans, then chopped it up with onions and potatoes until the whole room smelled like salt and fat and something indefinable—like a Sunday breakfast that had taken a wrong turn into an industrial yard.

When the first prisoners reached the serving line, they hesitated.

A cook with forearms like hams slapped a scoop of corned beef hash onto a tray. “Next.”

The first German woman, thin as a fence post, stared at the mound like it was alive. Her mouth opened, closed. She looked at the tray, then at the cook, then at Lennie, as if Lennie might translate the laws of nature into something edible.

She said something in German, fast and sharp.

Lennie didn’t understand a word, but the tone was universal: What in God’s name is that?

The tall woman—Liesel—stepped forward and spoke in careful, accented English that sounded like it had been learned from a book and sharpened by necessity.

“What is… this food?”

The mess hall seemed to pause. Even the wind held its breath outside.

The cook blinked at her, then at Lennie, as if Lennie were responsible for the existence of corned beef on earth. “It’s corned beef,” he said, like that settled it. “Hash.”

Liesel’s brow wrinkled. “Corn… and beef?”

“It’s beef,” Lennie said, stepping closer. “Cured. Salted. Not corn like corn-on-the-cob. ‘Corned’ means… little grains of salt. Old word.”

Liesel stared at the tray. “So it is… beef with salt.”

“Pretty much,” Lennie admitted. “And potatoes.”

Another German woman leaned in, sniffed, then recoiled like she’d been insulted by the aroma. She said something that made a couple of her friends laugh under their breath—small, startled laughter, the kind you couldn’t stop even if you wanted to.

Liesel translated with a flicker of embarrassment. “She says… it smells like… like a boot that has been boiled.”

The cook’s face reddened. “Well, nobody’s forcing you—”

“They will eat,” an MP snapped, not cruelly, just tired. “Move it along.”

Lennie raised a hand. “It’s all right,” she said to the MP. Then, to Liesel, softer: “It’s not fancy. But it’ll fill you up.”

Liesel didn’t smile. She lifted her tray and walked to a bench where the others were sitting in clusters like birds that didn’t yet trust the feeder.

Lennie watched them take their first bites.

It happened in stages.

First, suspicion: small nibbles, jaws working cautiously, eyes darting to see if anyone else was making a face. Then the salt hit, and a few blinked hard, not used to flavor that didn’t taste like rationed misery. A red-haired girl coughed as if she’d swallowed a mouthful of the sea. Someone reached for coffee like it was a life raft.

Then, unexpectedly, the hunger did what hunger always did. It pushed pride aside. It rewired disgust into acceptance. A woman who’d looked ready to cry over the tray took a second bite, then a third, faster now. Another scraped the last bits with a piece of bread, like she didn’t want to waste a single crumb.

Liesel ate slower, watching as she chewed, as if she were analyzing the enemy through her teeth.

Lennie had other tasks—inventory, headcounts, forms that needed signatures—but she found herself drifting toward that bench again and again, like a magnet that didn’t want to admit it had a pull.

On her third pass, she heard German words sprinkled with the only English the prisoners seemed to share: “corned beef,” said the way you might say “meteor” or “frog.”

Liesel looked up and, to Lennie’s surprise, gestured at the empty spot beside her.

Lennie hesitated. Regulations weren’t written for this kind of moment. But the MPs were bored, the cooks were busy, and the war was near its end in a way you could feel in the air—like a storm that had spent itself but hadn’t yet cleared.

So Lennie sat.

Up close, Liesel’s face showed its exhaustion. A bruise-yellow shadow under one eye. Dry skin at the corners of her mouth. Hands that were clean but not soft.

“You do not eat,” Liesel observed.

“I already did,” Lennie said. “Back when it was still hot and I had the choice.”

Liesel studied her. “You are… soldier. But you are not in front.”

“Neither are you,” Lennie replied before she could stop herself.

A faint flash—something like a smile, but less kind—touched Liesel’s lips. “No. But war is everywhere.”

On the bench, a smaller woman—Greta, according to Lennie’s clipboard—held up a forkful and spoke rapidly to Liesel, eyes wide. Liesel listened, then translated.

“She asks why the meat is… square,” Liesel said, deadpan.

Lennie laughed, just a short bark that startled her. “Because it comes out of a can,” she said. “Everything comes out of a can if you’re far enough from home.”

Greta frowned, then, in halting English, asked, “In America… you have so much metal?”

Lennie glanced at the stacks of tins. At the pots. At the mess-hall equipment that looked like it could survive a tornado. “Yeah,” she said. “We’ve got metal.”

Greta said something in German that made three women snort, and Liesel translated, a little reluctantly: “She says… then it is true. America is made of machines.”

Lennie looked at the women—at their hollow cheeks and patched coats—and felt something in her chest pinch.

“You’ve had worse,” Lennie said quietly.

Liesel’s gaze went somewhere distant, like a radio tuning past static. “In 1944, we had a soup,” she said. “It was water and cabbage that had given up. We called it ‘hope soup’ because it tasted like you must imagine food.”

Greta murmured something.

Liesel’s voice stayed steady. “She says your corned beef tastes like you do not imagine food. You have it.”

Lennie swallowed. She didn’t know what to do with that—gratitude, resentment, accusation, all tangled up.

So she did the only thing she could think of. She pointed at Liesel’s tray. “So… is it boot? Or not boot?”

Liesel looked at the remaining hash as if it were a puzzle. “It is… not boot,” she decided. “It is… heavy. Like a stone in the stomach.”

“That’s the point,” Lennie said. “Stones don’t run away.”

A laugh went around the bench. Small. Real. It surprised everyone, including the women who made it.

After that first meal, corned beef became a kind of language in the camp.

It showed up in stew, in sandwiches, mixed with eggs on mornings when the kitchen had eggs. The women started calling it “the square meat” among themselves, and even the MPs picked it up, because soldiers would rather borrow a nickname than learn a word correctly.

Lennie learned bits of German the way you learn songs you hear too often: Danke. Bitte. Schmeckt. She learned that Kartoffel sounded like a joke but meant potato. She learned that if you brought extra onions down to the kitchen, you could trade them for a better meal. She learned that a lot of the women had been promised glory and received mud.

And Liesel—who’d been stone-faced on the first day—began to talk, not warmly, not quickly, but like someone testing whether truth would cost her something.

She told Lennie about listening to British broadcasts on the radio and translating them for officers who pretended they weren’t scared. She told Lennie about the long retreat through towns that looked like they’d been chewed up. She told Lennie about her brother, drafted into the army at seventeen, who wrote letters from somewhere in the east and then stopped writing.

One afternoon, as Lennie was tallying supplies near the kitchen, Liesel appeared at the doorway holding a folded scrap of paper.

“I have a question,” Liesel said.

Lennie looked up. “Shoot.”

Liesel hesitated, then handed her the paper. It was a recipe, written in neat German script. Lennie could make out one word: Rindfleisch. Beef.

“This is… my mother’s,” Liesel said. “She made it on Sundays. Before.” Her jaw tightened on that last word, as if “before” was a country she’d been exiled from.

Lennie turned the paper over like it might reveal a secret map. “You want me to—what—cook it?”

Liesel’s shoulders lifted in the smallest shrug. “Maybe you tell your cook. Maybe he makes something… not from a can.”

Lennie glanced back into the kitchen, where the head cook was currently yelling about missing ladles like they were deserters. “You ever tried telling a U.S. Army cook what to do?”

Liesel’s eyes narrowed. “It cannot be more difficult than telling a German officer he is wrong.”

Lennie laughed again, and this time it came easier. “All right,” she said. “I’ll try.”

It took two weeks, three favors, and one near-argument with the supply sergeant, but Lennie managed to get the ingredients close enough—beef, onions, a bit of vinegar, bay leaves. The cook grumbled, but he was curious, too, in the way men were curious about anything that broke routine.

On the day they made it, the mess hall filled with a smell that wasn’t just salt and heat. It smelled like something with a history.

The German women ate it slowly, almost reverently, and for the first time since they’d arrived, Lennie saw tears on someone’s face—not from fear or exhaustion, but from memory.

Greta wiped her eyes and said in English, “This is… home.”

Lennie didn’t know what to say, so she said the only honest thing. “Yeah,” she murmured. “Food does that.”

The war, meanwhile, kept lurching forward like a wounded animal.

Newspapers arrived with headlines that grew stranger every week: cities fallen, armies collapsing, names that sounded like myth because they were too big to fit in a human mouth. The camp had a radio in the office, and the MPs listened in the evenings, faces turned toward the static as if it might confess something.

One night in early May, the camp siren didn’t wail, but the camp felt different anyway. Like the air was braced.

Lennie was in the administration shack, filing forms, when the sergeant burst in with a newspaper in his hand. His eyes were wide in a way she’d never seen.

“It’s over,” he said.

Lennie’s fingers froze on the paper stack. “What?”

“Germany surrendered,” he said, almost breathless. “Unconditional. Signed yesterday.”

For a second, Lennie couldn’t make the words connect. The war had been her whole adult life, her whole horizon. The idea of it ending felt like someone telling her gravity had been canceled.

Outside, a cheer went up from the American side of the camp—shouts, clapping, a whoop that sounded half wild.

Then, from the POW barracks, a different sound rose: not cheering, not exactly. A murmur. Voices overlapping. A sharp cry. Then silence, heavy as a door closing.

Lennie walked out before she knew she was moving. Past the fence line that separated “us” from “them.” Past the watchtower shadow. She stopped at the gate, where an MP eyed her, then let her pass with a shrug that said, What difference does it make now?

The German women were gathered in their yard, clustered in tight knots. Some stood rigidly, staring at nothing. Some had their hands over their mouths. Greta sat on the ground, rocking slightly, her face wet.

Liesel stood apart, arms folded, as if she’d decided the news couldn’t touch her if she didn’t let it.

Lennie approached carefully, like you approached an animal that might bolt. “Liesel,” she said.

Liesel’s eyes flicked to her. “It is finished,” she said in English, and her voice was flat.

“Yeah,” Lennie said. “It’s finished.”

A long silence stretched between them, filled with wind and distant American cheering.

Then Liesel’s face did something Lennie hadn’t seen before: it cracked. Not with tears, not with anger—just a brief tremor around the mouth, like a dam shifting.

“My mother,” Liesel said, and the words came out rough. “My city. My brother.” She swallowed hard. “I do not know what is left.”

Lennie felt a sting behind her own eyes, sudden and unwelcome. She thought of her own mother’s letters. Of her brother Sam, who’d been too young to enlist and too old not to understand why Lennie left.

“I don’t know either,” Lennie admitted. “But… you’re alive. That’s something left.”

Liesel’s gaze sharpened. “Alive,” she echoed, as if tasting the word. Then, very quietly, she said something in German that Lennie didn’t understand.

Greta looked up from the ground and said, in English, “What now?”

Lennie didn’t have an official answer. Official answers came in typed orders and stamped envelopes, and they took weeks.

So she gave an unofficial one. “Now we feed people,” she said. “Now we wait for trains and ships and paperwork. Now we try to get everyone home—wherever home is.”

Greta blinked. “Even… us?”

Lennie nodded. “Even you.”

That night, the cook opened more cans than usual. Not because he cared about symbolism, but because there was a kind of nervous energy in the camp that needed something to do. He made corned beef hash and set it out in steaming pans like always.

Lennie carried an extra tray to the fence line, where the Germans were being marched in for supper under watchful eyes. Liesel’s group was in the middle.

When Liesel saw Lennie waiting with the tray, she slowed.

“What is that?” Liesel asked, though they both knew.

Lennie held it out. “Square meat,” she said. “With onions. Better than boot.”

For a moment, Liesel didn’t move. The war had ended, but pride didn’t surrender on schedule.

Then she took the tray—careful, like it might burn her even though it wasn’t hot enough to hurt—and nodded once.

“Thank you,” she said.

It wasn’t an emotional speech. It wasn’t forgiveness. It wasn’t friendship, exactly.

But it was something that existed in the space after fighting, when people were forced to become human again.

They sat, Americans at one end of the hall, Germans at the other, separated by habit more than distance. The same roof. The same dust. The same wind worrying the building like it wanted in.

Greta took a bite and grimaced theatrically, and one of the women laughed, and the sound traveled farther than it used to. An MP pretended not to watch. A cook pretended not to listen.

Lennie caught Liesel’s eye across the room. Liesel lifted her fork slightly—half salute, half acknowledgment—and went back to eating.

Outside, the barbed wire still sang when the wind hit it just right.

But the note sounded different now—not like laughter, not like menace. More like a reminder that even the sharpest fences were temporary.

And in the middle of all that temporary steel and paperwork and history, a strange American can of corned beef had done the one small thing food sometimes does in wartime:

It had made enemies pause long enough to taste each other’s world.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.