What Churchill Said When Patton Did in One Day What Took Others a Mont

The map of Germany covered the wall like a wound that refused to close.

In the underground war rooms beneath London, under concrete and steel and the muffled rumble of a city that had forgotten what silence felt like, Winston Churchill stood with his hands clasped behind his back, a cigar smoldering between his fingers, staring at the sinuous blue line that cut across the map from north to south.

The Rhine.

Thin, neat pins marked bridgeheads, divisions, army groups, airfields, supply dumps. Colored yarn laced the wall in a spiderweb of intentions. Brass lamp shades poured harsh white light down on it all, turning the rivers into veins of light and the forests into smudges of shadow.

Churchill’s gaze kept returning to the western bank of the Rhine, to the dense cluster of pins and flags north of the Ruhr. The British Second Army. The American Ninth Army. The great concentration of men and machinery that Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery had gathered like a man arranging priceless porcelain before a ceremony.

He drew on his cigar, watched the smoke drift up and flatten against the low ceiling.

“Twenty-fourth of March,” he muttered, half to himself. “We have been promised the twenty-fourth.”

It was March 22, 1945.

Above him, London slept in patches. In the East End, a few pubs stayed open longer than regulations allowed, serving men who would never see the front and those who had already seen too much of it. Somewhere, a baby cried. Somewhere, a couple whispered about the future as if it were a piece of contraband.

Down here there was only the ticking of clocks, the rustle of paper, the clink of teacups and ashtrays. The war rooms hummed with the quiet, relentless activity of officers and clerks and messengers tracking a war that was now, by all rational accounts, nearly won—and yet continued to devour lives every hour.

Churchill turned from the map and glanced at General Ismay, who was standing a respectful distance away, a folder tucked under his arm.

“Monty assures us again?” Churchill asked. “Everything ready and in order? Every gun aligned, every shell accounted for, every boot polished?”

“Yes, Prime Minister,” Ismay said. “Operation Plunder is on schedule. The crossings will begin on the twenty-fourth at 2100 hours. The artillery preparation is to be… extensive.”

Churchill snorted softly.

“Extensive,” he repeated. “That’s one word for it. Biblical might be another. He means to convince the Hun that the Day of Judgment has arrived and that it is, unsurprisingly, under British management.”

There was a faint twitch at the corner of Ismay’s lips, quickly suppressed.

“He is confident of success, sir.”

“Yes,” Churchill said. “That’s the trouble. Monty is always confident—once everything has been arranged to his satisfaction. He likes his wars like he likes his tables: properly set before anyone is allowed to sit down.”

He walked back toward the map, the soles of his shoes muffled against the linoleum.

“We must cross,” he said quietly. “We cannot just sit here, peering at the river as if it were a pretty canal. Every day we wait, the Germans dig a little deeper, shift another battery, lay another mine. And Ivan”—he tapped a stubby finger on the eastern edge of the map, near the Vistula—“keeps moving west. He is not waiting for the twenty-fourth.”

No one answered. There wasn’t much to say. The Soviets were a fact like gravity—a force that pulled everything east of Berlin toward itself.

Churchill raised the telegram in his hand—Montgomery’s latest reassurance. The words were calm, precise, measured. On schedule. Perfectly prepared. Zero risk.

He folded it back into its envelope, slipped it in his pocket, and checked his watch. Nearly three in the morning. Another night spent pacing between maps and reports and the stale air of underground rooms.

He was about to ask for more tea when the door opened and a young officer stepped in, breathless, a cream-colored envelope clutched in his hand.

“Message from Supreme Headquarters, sir,” the officer said. “Marked urgent.”

Churchill’s eyebrows rose. Eisenhower rarely sent messages at this hour unless something had gone terribly wrong—or unexpectedly right.

“Bring it here,” Churchill said.

The envelope changed hands. Churchill tore it open with a practiced flick of his fingers and unfolded the flimsy sheet inside.

For a moment the rustle of papers in the room muted, as if the air itself were holding its breath.

His eyes moved quickly over the words. Then they went back and read them again, more slowly. The cigar drooped dangerously at one corner of his mouth.

Without a word, he reached for his reading glasses, perched them on the end of his nose, and read the message a third time.

Ismay watched a subtle change come over the Prime Minister’s face. Some of the color drained from his cheeks. His habitual frown lines deepened—but not into anger or fear. Something else. Astonishment, edged with something that might have been bitter amusement.

Churchill lifted his head.

“Patton,” he said.

Just the name. No rank, no explanation. As if that alone carried a freight of significance.

Ismay stepped closer. “Sir?”

Churchill held the flimsy out.

“Read that.”

Ismay took it carefully, eyes scanning the typed words.

THIRD ARMY HAS CROSSED THE RHINE IN FORCE NEAR OPPENHEIM. BRIDGEHEAD ESTABLISHED. ENEMY OPPOSITION LIGHT. CASUALTIES MINIMAL. OPERATION CONDUCTED WITHOUT PRELIMINARY BOMBARDMENT OR AIR SUPPORT STOP PONTOON BRIDGE UNDER CONSTRUCTION STOP TANKS TO CROSS THIS MORNING STOP

SIGNED: GEORGE S. PATTON, JR.

Ismay read it again. The words seemed absurd on the face of them. Without bombardment. Without air support. Minimal casualties. Crossed the Rhine.

“This was sent yesterday,” Churchill said. “Late on the twenty-second. It has taken its time getting here. In the meanwhile our Monty is still arranging his fold-up chairs for the grand performance.”

He took the flimsy back and stared at it as if it were a piece of enemy propaganda he was trying to find the trick in.

“He did it,” Churchill murmured. “The madman actually did it.”

There was admiration there, and exasperation, and a faint sting. Britain’s carefully prepared, meticulously orchestrated crossing had just been pre-empted by an American general who believed that if a thing could be done today, doing it tomorrow was a kind of crime.

Churchill turned slowly back to the map. His gaze traced the Rhine’s course until he found Oppenheim, a little nothing of a town between Mainz and Worms that had barely warranted a pin.

He had to squint to see it. A river bend, a stub of a road, a name in small letters.

There, he thought. There he went.

He leaned heavily on his cane and, for a moment, drifted back—not to Oppenheim, which he had never seen—but to a hundred conversations, arguments, and memos that had flown back and forth across the Channel over the preceding months.

Montgomery’s voice: precise, clipped, speaking of bridges, artillery, airborne operations, artillery again, logistics, timing, coordination.

Patton’s voice, heard only in scraps and reports and complaints. Aggressive, impatient. Always wanting to move faster, strike harder, take the risk.

Caution and audacity, drawn up like opposing doctrines on either side of a river.

Two hundred miles south of Montgomery’s sprawling encampments, the Rhine did not feel like a line on a map. It felt like an animal.

Cold mist rose from the dark water, clinging to the low banks and the willow trees like a living thing. The current slid past with a soft, relentless sound, occasionally slapping against the hulls of small boats pulled up on the western bank.

Oppenheim slept uneasily behind the river. Its tiled roofs and shuttered windows were laser-scanned nightly by Allied reconnaissance aircraft. The bombers had spared it so far; there were larger, juicier targets in the Ruhr and beyond. But the town had learned to live with the distant thunder of bombs and the way the sky sometimes glowed faintly orange to the north.

On the western bank, under the cover of that same darkness, men moved in silence.

Private Joe Carlin of the 11th Infantry Regiment pulled his gloves tighter as he waited in the predawn chill. His breath rose in little white puffs that quickly vanished, swallowed by the damp air. There was a faint tang of fuel, river water, and canvas in his nostrils.

He was twenty years old and had been in Europe long enough to know that when officers said “light resistance expected,” someone was usually wrong.

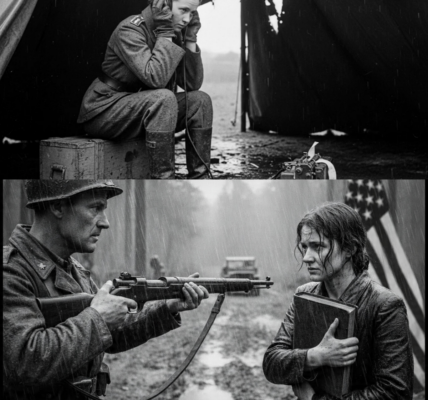

Beside him, Sergeant Kowalski shifted the weight of his gear and glanced toward the line of figures a few yards ahead, where a single tall officer stood outlined against the faint glow of the sky—the only man with his helmet pushed back at a jaunty angle, the only man whose stance radiated impatience rather than fear.

Patton.

Everyone knew his silhouette. The helmet with its stars. The straight, aggressive line of his shoulders. The ivory-handled pistols at his belt caught a stray glint of light when he turned.

“Quit starin’, Carlin,” Kowalski muttered softly. “He’s not gonna adopt you.”

Carlin forced a smile, though his stomach was tight.

“I heard he crossed a river in Italy the same way,” Carlin whispered back. “No prep, no big guns. Just went over.”

“He’d cross the damned Atlantic in a rowboat if they’d let him,” Kowalski said. “Now shut it.”

An officer walked down the line, bending low, whispering to each cluster of men.

“When the word comes, you move fast and quiet,” he murmured when he reached Carlin’s boat. “No talking. No smoking. You don’t fire unless you absolutely have to. Surprise is your best friend tonight.”

Carlin nodded, feeling the bulk of his rifle against his shoulder, the unfamiliar weight of the life vest strapped around his torso.

He had heard about the Rhine since basic training. The big river. The last barrier. Teachers back in Ohio had spoken of it in dusty lectures as if it were something ancient and permanent and imposing, like the Great Wall of China or the Alps. Now here he was, about to cross it in a wooden assault boat with a handful of men he barely knew.

On the slight rise behind them, Patton’s staff officers huddled over a map spread on the hood of a jeep. A red-faced colonel jabbed his finger at a point on the far bank.

“The Krauts pulled most of their decent units north,” he said in a low voice. “Our intel says they’ve got a few Volkssturm, some second-rate troops. Artillery is thin. They’re expecting Monty’s circus up near Wesel, not us down here.”

A brigadier shook his head slowly.

“Still,” he said, “it’s the Rhine. That’s not a creek we’re talking about. If they’re wrong about the defenses—”

Patton cut him off without looking away from the dark water.

“If we’re wrong, we find out quick and we keep going,” he said. His voice was calm, almost conversational, but it carried.

He had spent the day striding up and down the riverbank, inspecting the boats, haranguing engineers, checking and re-checking the plans. His staff had learned to recognize a particular energy in him when he was about to gamble big: his movements went from jerky to smooth, his profanity became almost poetic, and he kept quoting old campaigns as if they were recent news.

“This is no worse than what Caesar did at the Rubicon,” he had told them that afternoon, standing with his hands on his hips as the engineers tested a section of pontoon. “Hell, it’s easier. He didn’t have motorized bridging equipment. The man crossed with nothing but legionnaires and a bad temper. We’ve got trucks.”

Now, as the last checks were made, he took off one glove and reached out, letting his bare fingers brush the air above the water as if feeling the river’s mood.

He had grown up on stories of rivers and charges and last stands told by uncles who still spoke of the Civil War as if it were yesterday. Some part of his mind was always staging reenactments, measuring himself against ghosts: Stuart, Jackson, Lee, Napoleon, Caesar. Men who had moved faster than their enemies thought possible and made history by not waiting for perfect conditions.

He turned to his corps commander.

“Ernie, if we wait long enough, they’ll move every last damn gun they have in Germany up to this bank and then Monty will tell us it’s unsafe to cross until the year 1950,” he said. “We’re going tonight.”

General Eddy nodded. There was no point arguing; the orders had already gone out.

A runner approached, saluted.

“Sir, the boats are in position. All units report ready.”

Patton looked at his watch. The luminous hands glowed faintly.

“Good,” he said. “Let’s get this bastard over with.”

He raised his arm and made a chopping motion toward the river.

“Send them,” he said.

Down on the bank, the whispered commands moved like a breeze through tall grass.

“Mount up. Let’s go. Keep it tight, keep it quiet.”

Carlin felt Kowalski’s hand on his shoulder pushing him forward.

They slid the assault boat into the water, boots splashing briefly before they hefted themselves in, two men to an oar, another at the stern. The river accepted the small weight with a soft rocking motion.

Someone shoved off. The bank slid away behind them, a dark, receding line. The low, familiar sounds of a military camp—clanks, murmurs, the growl of engines—faded, replaced by the steady, quiet dip of oars and the faint hiss of the current.

Carlin focused on the rhythm. Pull. Breathe. Pull. Breathe. The cold bit his fingers through the gloves. His thoughts narrowed until there was only the weight of the oar, the feel of the boat, and the looming shadow of the far bank.

Ahead, the eastern shore was a darker smear against the sky. Somewhere in that darkness there were German sentries, foxholes, boys his age with rifles cradled across their laps, shivering in the cold and wondering where the next bombardment would fall.

One of those boys, Hans Vogel, stood in a shallow trench above the river, half-hidden behind the splintered remains of a tree trunk. He had been nineteen for exactly five days. His boots were too big. His field cap itched. His rifle had been issued to three other men before him.

The war had been going on for as long as he could remember clearly. It had gone from parades and flags to bombed houses and hunger and listening to his mother cry after the newsreels ended. Now it was a river and the knowledge that on the other side of it were more Americans than he could count.

He stamped his feet to keep the feeling in them and stared out across the water. The night seemed empty. No flares, no explosions, no searchlights.

He preferred it when the sky lit up. At least then he knew where death was coming from.

He yawned, blinked, and rubbed his eyes. It was the dead time of night when the body demanded sleep whether the mind liked it or not.

Behind him, in a small dugout, his sergeant sat hunched over a little radio, twiddling dials, trying to pull in the nightly propaganda broadcast from Berlin. He smacked the side of the box.

“…enemy attacks in the north expected…” a thin voice crackled and then dissolved into static.

Hans leaned on his rifle and peered into the darkness.

The Rhine whispered.

Nothing moved.

On the water, a flotilla of low silhouettes drifted forward.

Carlin heard the distant rumble of artillery from somewhere far to the north—the constant, background thunder of Montgomery’s buildup. It sounded like a storm brewing beyond the horizon.

“Think they know we’re coming?” he whispered without meaning to.

Kowalski’s elbow found his ribs.

“Shut it,” he breathed. “You want to write ‘Dear Jerry, we’re right here’ in the sky?”

Carlin clamped his mouth shut and swallowed.

Their boat drew closer to the eastern bank. He could see it now: the faint line of reeds, the darker hump of the ground behind them, a suggestion of uniformed shapes, maybe, or just shadows.

His heart was beating too fast. He tried to count the strokes on the oar to steady himself.

Thirty yards. Twenty. Ten.

A sudden scraping sound jolted through the hull. The bow dug into mud.

“Out!” hissed the lieutenant at the stern. “Go, go, go!”

They splashed into knee-deep water, boots filling with cold, each step a sucking weight as they waded up the bank.

Carlin’s senses sharpened to a painful clarity. The smell of wet earth and river. The slight crunch of gravel under his soles. The rasp of his own breath. The weight of the rifle in his hands.

A figure loomed in front of him, wide-eyed, mouth opening.

Hans saw ghosts rising out of the water. For a second his mind refused to accept that they were Americans, that they were here, this close, without the roaring prelude of artillery.

He fumbled with his rifle, fingers clumsy with cold and surprise.

Kowalski’s bayonet hit him in the chest before he got the safety off.

The first sound of combat on the Oppenheim sector of the Rhine that night was not a gunshot. It was a strangled cry, quickly smothered.

After that, things happened fast and quietly.

Patton’s infantry spread out from the landing points like ink soaking into paper. They moved from shadow to shadow, clearing trenches and dugouts with grenades and bayonets, whispering “Hands up” in bad German and “Don’t shoot, don’t shoot” in better.

A machine-gun nest that should have commanded the bend of the river fell without firing a single burst because its crew had been half asleep, wrapped in blankets, ears tuned for the sound of aircraft and artillery—not for the splash of paddles.

A small artillery battery, four guns and a few harried gunners, found itself peering down their own barrels at Americans who had come up from the river like wraiths, faces blackened, helmets low.

By the time the eastern horizon began to pale with the first suggestion of dawn, a bridgehead had taken shape where, according to every cautious plan, one should not have existed yet.

Patton stood on the western bank, watching the second wave of boats cross. The mist curled around his boots. He chewed his cigar, which had long since gone cold, and kept up a running commentary that was half prayer, half profanity.

“That’s it. Keep those goddamn paddles moving. Faster. The Rhine won’t wait for you to make up your mind. You see that?” He jabbed a finger toward the far shore, where a faint scatter of muzzle flashes winked. “That’s what happens when you give the enemy time. A little, we can handle. A lot, and you’re writing letters to mothers instead of reports.”

An engineer captain trotted up, saluted briskly.

“Sir, we’ve got the first section of the pontoon in position. We can start bringing up the treadway. We’ll need another four hours before we can take armor.”

“Three,” Patton said. “You’ve got three. And if you can’t do it in three, you can damn well lie and tell me you did.”

The captain hesitated, then nodded.

“Yes, sir.”

He turned and ran back toward the waiting trucks, where men were already muscling metal sections into place, cursing and grunting, their breath smoking in the cold air.

Patton watched him go, then looked back at the river.

“All my life,” he said softly, not caring who heard, “I’ve wanted to piss in this goddamn river.”

A few of his staff chuckled nervously.

He walked out along the first completed stretch of the pontoon bridge, boots thudding hollowly on the metal plates, the water swirling beneath him. Halfway across, he stopped, unzipped his trousers, and relieved himself into the Rhine with an expression of immense satisfaction.

“Take a good look, boys,” he said over his shoulder. “The last son of a bitch who thought he owned this river is hiding in a bunker in Berlin. It’s ours now.”

Behind him, across the water, distant small-arms fire crackled sporadically. None of the bullets came close enough to disturb the moment.

By the time the sun had fully cleared the horizon, the Third Army had a solid bridgehead. The first self-propelled guns rumbled across the pontoon bridge, their tracks vibrating the makeshift structure. Behind them came the tanks—the same tanks that had raced across France, now grinding forward once more, turrets swiveling, crewmen squinting at the unfamiliar German landscape unrolling beneath their tracks.

In a small command post hastily set up in a farmhouse near the river, a radio operator hunched over his set, headphones pressed tight to his ears. A sergeant stood beside him, taking down the dictated message.

FROM: CG THIRD ARMY

TO: SUPREME HEADQUARTERS ALLIED EXPEDITIONARY FORCE

SUBJECT: RHINE RIVER CROSSING

THIRD ARMY FORCES HAVE CROSSED THE RHINE NEAR OPPENHEIM WITHOUT BENEFIT OF AIR BOMBARDMENT, ARTILLERY PREPARATION, SMOKE, OR AIRBORNE ASSISTANCE STOP BRIDGEHEAD SECURE STOP ENGINEERS CONSTRUCTING BRIDGES STOP ENEMY RESISTANCE LIGHT STOP

SIGNED: PATTON

The sergeant passed the sheet to the communications officer, who read it, smirked, and added, under his breath, “Message to Monty: catch up.”

The message sped outward through cables and airwaves, hopping from headquarters to headquarters, until it ended up in the hands of men who had spent months listening to arguments between caution and audacity.

At Montgomery’s headquarters, farther north along the Rhine, the mood that morning could not have been more different.

The field marshal’s tent was as orderly as a well-run parlor. Maps lined the walls in neat rows. Tables held stacks of files, each stack squared, labels facing outward. A faint smell of pipe tobacco and starch hung in the air.

Montgomery stood before his operations map, a swagger stick tucked under his arm, his beret worn at a precise angle. Senior officers crowded around, some seated, some standing, all with notebooks or folders in front of them.

“Gentlemen,” Montgomery said, “tomorrow night we execute the most meticulously planned river crossing in the history of warfare.”

He let the statement hang in the air for a moment.

“We will bring to bear a weight of artillery and airpower that will make the Germans wish they had never heard of the Rhine, let alone chosen to stand on its banks. Every battery has its assigned target. Every infantry platoon knows its starting point and its objective. Our airborne forces”—he tapped a section of the map farther inland—“will drop here, here, and here to seize the high ground and disrupt enemy communications.”

He began walking along the map, his swagger stick tracing arcs in the air.

“The key, as I have always said, is preparation. We do not improvise on a river as formidable as this. We do not risk men’s lives on slapdash schemes. We ensure that when we move, we move with overwhelming force and absolute clarity.”

He paused, and a faint smile tugged at one corner of his mouth.

“I am told some of our American colleagues take a different view. They are fond of charging ahead and hoping for the best. That is not our way.”

There were polite chuckles around the tent.

A staff officer coughed discreetly.

“Sir,” he said, “there is a message from Supreme Headquarters. Just arrived. Marked urgent.”

Montgomery’s fingers tightened slightly on his swagger stick. He did not like interruptions to his briefings. Still, Ike would not send something marked urgent at this stage without good reason.

“Very well,” he said. “Let’s hear it.”

The officer unfolded the flimsy and read aloud.

As the words crossed, Rhine, Third Army, Oppenheim, without artillery preparation, without air support, bridgehead secure, Montgomery’s jaw tightened almost imperceptibly. The joviality leaked out of the tent like air from a punctured balloon.

Silence followed the last word.

Montgomery cleared his throat.

“Well,” he said, his voice carefully neutral, “it seems General Patton has elected to… take the initiative.”

One of the British corps commanders, a solid man with a weathered face, shifted uneasily.

“Damned risky, if you ask me,” he said. “No proper bombardment? No smoke? If that had gone wrong—”

“It would have been a massacre,” another officer finished.

Montgomery seized on that.

“Quite,” he said. “Precisely why we do not conduct operations in such a manner. A single success obtained by defiance of sound principles does not invalidate those principles. If anything, it encourages recklessness.”

He turned back to the map, forcing his attention to the brightly colored pins and strings.

“Our operation proceeds as planned. We do not alter our timetable to race anyone. We are here to win the war, not a popularity contest.”

But as he spoke, the map in front of him seemed subtly altered. That neat blue line of the Rhine no longer represented a virgin obstacle waiting for his touch. Somewhere, down in small letters between Mainz and Worms, Patton had already written his name across it.

Montgomery’s staff absorbed the news in murmurs and sideways glances.

In the enlisted lines outside, rumors outran official information, as they always did.

“Yanks crossed already, they say,” a British sergeant told his mates as they huddled around a small brazier, hands extended toward the meager warmth.

“Bollocks,” one of them said reflexively. “Across the Rhine? Without us? Pull the other one.”

“I’m telling you,” the sergeant insisted. “Bloke from the signals unit says Third Army’s over the river near some place called Oppenheim. Quiet as you like. No barrage, no nothing.”

The men looked toward the river, which was invisible from where they sat, hidden by a gentle rise and a line of trees.

“So we’re what, then?” someone asked. “The encore?”

The sergeant shrugged.

“Doesn’t change what we’ve got to do,” he said. “Come tomorrow night, we’ll make enough noise for both sides of the river.”

Back in London, Churchill dictated his reply to Montgomery with a cigar clenched firmly between his teeth.

The stenographer sat poised, pen scratching across the page as Churchill prowled the small office, words spilling out in a harsh, sardonic rhythm.

“Inform Field Marshal Montgomery,” Churchill said, “that his preparations for the Rhine crossing are most impressive. However, I am bound to observe that events appear to have moved rather more quickly than his arrangements.”

He paused, savoring the subtle sting of the phrase.

“The enemy, I fear,” he went on, “has been granted the dubious pleasure of finding us somewhat behind the pace.”

Ismay shifted his weight. It was as close to a reprimand as Churchill would ever commit to paper, but the frustration behind it was real enough.

“Add,” Churchill said, “that we look forward to his early success—for which all necessary means have been so amply provided.”

The pen scratched.

He stopped pacing and stared at the wall for a moment, seeing not paint and plaster but the river that had obsessed planners for months.

“It is not that Monty is wrong in principle,” he said quietly, more to Ismay than to the stenographer. “Preparation saves lives. Men should not be thrown away on frivolous charges. But by God, there is such a thing as over-preparation. One can prepare so long that the moment passes by altogether.”

Ismay nodded.

“Patton has always preferred to seize the moment and apologize later,” he said.

Churchill smiled thinly.

“Let us hope,” he said, “that in this case, apologies will not be necessary.”

But part of him already knew—he could feel it like pressure behind his eyes—that when history came to write its verdict on the crossing of the Rhine, it would not list events in order of artillery tonnage expended.

It would remember who moved first.

While Montgomery’s guns were being aligned and his airborne troops briefed, Patton’s tanks were already rolling eastward, raising dust on German roads that had not yet learned to fear American treads.

In the towns they passed, civilians peered from behind curtains and cracked doors, eyes blank with exhaustion and fear. Some waved white cloths. Some simply stared, knowing that their world had finally, irreversibly changed hands.

At a small crossroads a few miles beyond the river, Carlin rode in the back of a truck, helmet pushed back, rifle between his knees. The crossing already felt like something that had happened in another life.

“You see the look on that Kraut officer’s face when we came up behind his battery?” Kowalski said beside him, shaking his head. “Like he’d just found a snake in his soup.”

Carlin smiled, then frowned.

“I keep thinking about that kid at the trench,” he said. “The one on the bank. He couldn’t have been older than me.”

Kowalski spat over the side.

“They all look young up close,” he said. “That’s how this works. You want to feel better, think about what would’ve happened if Monty had waited another two weeks and then tried his big show. Every one of those guns we caught sleeping tonight would’ve been pointed right at some poor bastard in a boat.”

Carlin thought about that, about the difference between the river they had crossed and the river it might have been—lined with dug-in machine guns, flares, pre-sighted artillery.

“How many do you think we lost?” he asked.

“Couple dozen, maybe,” Kowalski said. “Heard the lieutenant say something about under forty.”

Carlin let the number roll around in his head.

Under forty.

It was forty too many for the men in question, but in the cold arithmetic of war, it was a miracle. They had taken a river that everyone had been telling them for months would cost thousands.

“Reckon the folks back home will ever know how close it could’ve been?” Carlin asked.

Kowalski grunted.

“Folks back home will hear that we crossed a river and now we’re goin’ to Berlin,” he said. “They won’t see the difference between doing it tonight and doing it after a month of sit-on-our-hands. That’s for the brass and the historians.”

He snorted.

“Assuming the historians don’t get bored and skip straight to the part where the war ends.”

In Berlin, in an underground bunker much deeper and worse lit than the one under London, Adolf Hitler stared at his own maps and shook with impotent rage.

“It is a lie,” he hissed when his staff first brought him the news that American forces had crossed the Rhine south of Mainz. “They are confusing reconnaissance units with major formations. Our defenses are strong on the river. The Allies are cowards, they will not cross without first destroying everything in sight.”

But reports kept coming in, from shattered division headquarters and scattered regiments.

Enemy armor east of the Rhine. Towns falling in rapid succession. A bridge at Oppenheim.

He swept his arm across the table, sending markers flying. Little wooden representations of divisions clattered to the floor.

“They should have attacked at Wesel,” he shouted. “That is where we prepared for them. That is where we concentrated our best units. Not this… nothing… this place that no one even—”

He broke off, choking on his own fury.

His staff said nothing. There was nothing they could say. Even if they had dared, there were no reserves left to plug the gap. The armies that might have counterattacked had been broken the previous year in the Falaise pocket, on the retreat from Normandy, in the Bulge.

Now the Rhine—the grand barrier that propaganda had touted for years as Germany’s invincible shield—had been breached not with a roar of artillery and a blaze of heroic destruction, but with quiet paddles in the dark.

On the night of March 24, Montgomery finally unleashed his masterpiece.

The skies above the northern Rhine turned white and orange as thousands of artillery pieces fired in carefully timed salvos. The ground shook. The air was a constant, pounding presence in the lungs.

On bomber airfields across England and the Continent, crews took off in near-continuous waves, engines thundering, bomb bays full. Their target lists were precise, each battery, crossroad, and defensive position marked and catalogued.

Paratroopers sat shoulder to shoulder in the bellies of transport aircraft, checking and rechecking their gear as the red and green lights cycled above the doors.

When they jumped, they filled the sky with canopies, specks drifting down into the chaos.

On the ground, British and American infantry climbed into assault boats much like Carlin’s had been two nights earlier, but their crossing took place under a man-made storm. Smoke shells bloomed along the river banks. Machine guns laid down curtains of suppressive fire. The roar was continuous.

To the men in the boats, it was terrifying. It was also, in its way, reassuring. The sheer scale of the preparation seemed to say: You are not alone. We have thought of everything. We have brought everything.

Churchill watched parts of it from the air. He flew over the Rhine in a small aircraft, peering down at the explosions and the ant-like movement of men and vehicles. He described it later as one of the most astonishing sights of his life.

And yet, even as he marveled, a part of his mind whispered that it was like seeing a curtain fall on a play whose ending he already knew.

Down below, in the spray and smoke, British soldiers fought hard and bravely. They took their objectives. They established their bridgeheads. They suffered casualties that, while acceptable on the ledger of a world war, were heavier than those at Oppenheim.

On the eastern bank, German defenders who had spent the last days watching Patton’s armor pour through the gap to the south fought with grim determination. They knew there was nowhere left to fall back to that would be anything but ruin.

In the days that followed, newspapers in London carried headlines about the crossing of the Rhine. Photographs showed British and American soldiers in boats, engineers building bridges, airborne troops landing in fields. The tone was triumphant, the emphasis shared.

But among those who saw the confidential reports and the dates and the casualty figures, the story was clear.

Patton had crossed first.

Patton had done in twenty-four hours, with a fraction of the resources, what others said could only be done after a month of preparation.

Some weeks after the war ended in Europe, Churchill sat in his study, a different kind of quiet humming around him now. There were no air raid sirens, no danger of bombs, only the dull rustle of peacetime beginnings and the political storms that would soon unseat him.

On his desk lay drafts of his memoirs, pages of notes, memos, clippings. The story of the war was unfolding again under his pen, this time with the luxury—and the burden—of hindsight.

He paused over a section heading: The Crossing of the Rhine.

He lit a fresh cigar and leaned back, eyes half-closed.

He saw again the map in the war rooms, the young officer rushing in with the telegram, the shock and the unbidden laughter. He remembered the strange emotion that had washed over him—a mix of relief that someone had finally seized the initiative, and a sting of national pride that it had not been his meticulous, over-supplied British field marshal who had done it.

He picked up his pen and began to write.

He did not savage Montgomery. That would have been pointless cruelty—and politically awkward besides. Monty had, after all, won battles that might otherwise have been lost. His caution had saved British armies at times when Britain could ill afford disaster.

But Churchill also did not hide his admiration for Patton’s Rhine gamble. Between the lines, in the weight given to certain episodes and the lightness with which others were treated, his verdict was clear enough.

He wrote of how wars were not won solely by piles of shells and carefully drawn arrows on maps, but by men who understood that timing was as much a weapon as artillery.

Of how every day spent waiting for “perfect” conditions was a day given to the enemy to strengthen, to entrench, to prepare killing zones.

Of how Patton’s daring crossing, carried out when and where the enemy least expected it, had saved the lives of thousands who might otherwise have died attempting a river that had been given time to harden into a fortress.

In another headquarters across the ocean, Eisenhower reached similar conclusions, though he expressed them less eloquently. In his post-war reflections, he noted how often his most successful operations had come when his commanders pressed forward aggressively, forcing the enemy to react rather than allowing him time to dictate the terms of battle.

Montgomery read these things in due course. They stung, but he consoled himself with his own accounts, his own explanations. History, he knew, was as much about who got to tell the story as about what had actually happened.

Patton did not live to read either man’s final, polished thoughts. He died in December 1945 from injuries sustained in a car accident in occupied Germany.

But before that, in the brief span of peace he enjoyed, he wrote letters home and spoke to officers and friends about the war they had just fought.

Of all his campaigns—the dash across France, the relief of Bastogne—his eyes lit up most when he spoke of the night at Oppenheim.

“We didn’t ask the river’s permission,” he said once to an assembled group of junior officers. “We just crossed it. If we had sat around saying ‘Can it be done? Is it safe? Have we accounted for every last detail?’ we’d still be on the west bank counting our ammunition.”

He spread his hands.

“You cannot make war safe, gentlemen. You can only choose where you take your risks. Take them when the enemy is confused and unprepared, not when he’s been given a month to dig in and sight his guns. A good plan today is worth ten perfect plans next week.”

The line would be quoted and misquoted endlessly, distilled into an aphorism on leadership that would make its way into business books and motivational speeches decades later, stripped of mud and blood.

For the men who had bent their backs to the oars that night, the lesson was less abstract.

Carlin returned home to Ohio with a duffel bag and a head full of fragments: the feel of the Rhine’s cold around his knees, the weight of the oar, the startled face of the German boy on the bank.

Occasionally, when people asked him what it had been like “over there,” he would find himself telling the story of the crossing.

“We went over in little boats,” he would say, hands unconsciously miming the rowing. “No big guns, not that night. No bombers. Just us and the river. The brass said it was a miracle we got across with so few casualties, but I figure the real miracle was that some general up the line didn’t decide to wait another week.”

The person listening would nod, not really grasping the significance.

“It must have been terrifying,” they’d say.

“It was,” Carlin would answer. “But I’ll tell you what would’ve been worse. Going over that river with the Germans wide awake and waiting.”

He did not know—could not know—that somewhere, across the ocean, British veterans who had crossed under Montgomery’s barrage had their own stories. Stories of night turning to day under flares. Of boats shredded by machine-gun fire despite all the preparation. Of friends killed in a river everyone had told them had been softened up enough already.

Different crossings. Same river. Different philosophies. Same war.

One quiet afternoon years later, in a university classroom filled with students who had never heard bombs fall in earnest, a history professor drew two timelines on the chalkboard.

On one he marked the dates: January—planning. February—preparation. March 24—Operation Plunder.

On the other he wrote: March 22–23—Patton crosses at Oppenheim.

He turned to his class.

“Here,” he said, “we see two ways of thinking about war. Montgomery represents preparation to the point of mathematical certainty. Patton represents calculated audacity—a willingness to act before all variables are known.”

A hand went up.

“Which one was right?” a student asked.

The professor smiled.

“That,” he said, “is the wrong question. Both were right, and both were wrong. Montgomery’s method saved lives at El Alamein and cost more than necessary at the Rhine. Patton’s daring won the race to the river and might have been a catastrophe under different circumstances. The real lesson is that in war, as in life, there is a cost to waiting and a cost to acting. We remember Patton’s crossing because he acted at the exact moment when the cost of waiting had become higher than the cost of going.”

He paused, then added:

“Winston Churchill understood that. That’s why, when he read the message saying Patton had crossed the Rhine in one night without the grand orchestration we had been promised for months, he laughed—not with joy, but with the bitter recognition that the future had once again favored the bold.”

The Rhine still flows between its banks, unconcerned with which army crossed it when. Tourists take river cruises now, sipping wine on the decks of comfortable boats, cameras clicking as they glide past castles and vineyards.

Every so often, a guide will gesture toward a town like Oppenheim and say, “Here is where American forces crossed the Rhine in 1945,” or gesture farther north and say, “Here is where the British launched their great crossing under Montgomery.”

The tourists nod, take pictures, move on.

The river remembers none of it. It just keeps going, as it did before Caesar, before Patton, before Montgomery, before Churchill stood in a bunker and read a flimsy piece of paper that told him history had just lurched a little faster than his plans.

But in the way we tell the story—in the way we weigh caution against audacity, preparation against initiative—that night at Oppenheim still matters.

It is there in every commander who decides to move before the last spreadsheet is perfect, every leader who weighs the imperfect options of now against the theoretically flawless plans of later.

It echoes in the simple, brutal calculus that Patton understood in his bones and Montgomery learned at the cost of his pride:

Sometimes the safest way across a dangerous river is not to wait until you’ve built the biggest bridge.

Sometimes, you just get in the boat and row.