U.S. Tanks Were Running Dry in the Frozen Ardennes—Until a Garage Mechanic Turned Junk Steel into a Refuel Truck That Kept the Column Moving. NU

U.S. Tanks Were Running Dry in the Frozen Ardennes—Until a Garage Mechanic Turned Junk Steel into a Refuel Truck That Kept the Column Moving

By the time the snow started falling sideways, we were already out of fuel—out of patience, out of sleep, and close to out of luck.

They don’t put that in the recruiting posters. They show you tanks charging forward like metal bulls and soldiers laughing beside a campfire, faces clean enough to belong in a magazine. They don’t show you a Sherman sitting dead in a Belgian ditch with its crew stomping their feet to keep warm, staring at the fuel gauge like it’s a cruel joke.

I was Ordnance—one of the guys who kept the machines breathing. My name’s Ben Rojas, and before the Army I was a mechanic in Toledo, Ohio, the kind of place where you can smell oil on a man before he even walks into the garage. In 1944, the Army learned what every trucking company already knew: engines don’t run on courage.

On December 19th, we rolled into a little village whose name I never learned to pronounce correctly—Noville? Neufville? Something with too many consonants and not enough vowels—because the German push had ripped the road network into ribbons. Our supply lines were tangled up behind us. The fuel trucks that were supposed to meet the armor at the next waypoint were either lost, stuck, shot up, or turned around by MPs who had no idea where the front line was anymore.

The Ardennes wasn’t supposed to be the front. It was supposed to be quiet. Trees, cold, maybe a few nervous patrols. Instead it was artillery thumps echoing through the forest and the kind of fog that felt personal.

I climbed out of my half-track and the wind slapped me with wet ice. The village looked like a postcard somebody had stepped on—stone houses, narrow lanes, smoke creeping from chimneys. A church steeple stood like a finger pointing at the gray sky.

Lieutenant Hayes found me before my boots stopped crunching.

He was a tanker, early twenties, face sharper than it had any right to be in winter. He had the look of a man who’d been promoted by necessity and kept alive by stubbornness.

“Rojas!” he shouted over the noise of engines idling. “How bad?”

I lifted my hands, palms up. My gloves were stiff with old grease and new frost. “Depends what you mean by bad, sir.”

His eyes flicked toward the line of Shermans along the road. Some were still rumbling, trying to keep their fuel from freezing and their crews from turning into statues. Others were quiet, silent hulks with their hatches open, men standing beside them blowing into their hands.

“Mean this,” he said. “We move in an hour. We don’t move, we get boxed in. How many of my tanks can you keep rolling?”

I stared at the nearest Sherman. Its crew chief held up a jerry can like it was a prayer offering. It was empty.

“Sir,” I said, “I can keep them rolling if you feed them. Right now they’re starving.”

Hayes’s jaw worked. “Fuel trucks?”

“None,” I said. “Radio says the route’s jammed. They’re rerouting. Might be tonight. Might be tomorrow. Might be never.”

A shell boomed somewhere far off, then another, like a door slamming in the distance.

Hayes leaned close. “We’ve got a German armored patrol poking around the crossroads three miles east. Battalion wants that intersection before dusk.”

“And we’ve got tanks that can’t reach it,” I said.

He stared at me like he wanted me to invent gasoline out of cold air.

Mechanics get that look a lot. People think wrenches are magic if you hold them with enough faith.

“Do something,” he said, and walked away.

That was the whole plan: Do something.

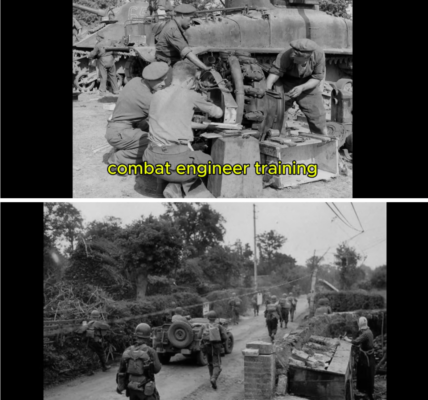

So I did what I’d always done. I looked around for parts.

Behind the church, there was a small workshop attached to a brick building that used to be a bakery. The smell still lived in the walls—yeast and flour, warmth trapped in stone. Now it was full of broken bicycles, a hand-crank grinder, and a delivery truck that looked like it had survived the war so far by being too miserable to bother shooting.

It was a little two-axle thing, mostly wood panels and dented metal. The engine compartment was open like a mouth, and the radiator had a crack big enough to stick a finger in.

My driver, Frankie Dugan, followed me in, hugging his jacket tight.

Frankie was from Brooklyn and could complain about weather like it was a competitive sport. He stared at the truck and said, “You gonna fix that? Or bury it?”

“I’m gonna use it,” I said.

“For what?” he asked.

I didn’t have the full picture yet. Just a feeling—an itch in my brain that said there had to be a way to turn something into fuel mobility. Because tanks didn’t just need fuel. They needed fuel where they were and when they needed it. The war didn’t wait for the quarterly delivery schedule.

I walked around the truck. The frame was solid. The bed was big enough for a few barrels. The tires were worn but held air. The cab had a broken windshield and a steering wheel that looked like it had been chewed by a dog, but it was a truck. It could move.

“If we can haul fuel,” I said slowly, “we can refuel the tanks right here and keep them rolling.”

Frankie blinked. “We don’t have fuel.”

“We have some,” I said. “Not enough, but some. The motor pool’s got a handful of drums. A few jerry cans. Maybe we can scrounge from abandoned vehicles.”

Frankie shook his head. “That ain’t a plan. That’s a wish.”

I tapped the truck’s bed. The wood felt frozen, hard as iron. “What I’m thinking is—we make a refuel truck that can hit multiple tanks fast. Not one can at a time. Something like a mobile pump station.”

He stared at me like I’d suggested we build a submarine.

“Ben,” he said, “we’re in Belgium. In winter. With Germans in the trees.”

“Yeah,” I said. “So we build it fast.”

Outside, engines coughed. A tank commander shouted at someone. The air felt like it was tightening.

I went back to the half-track and grabbed my tools—wrenches, a battered toolbox, lengths of hose, clamps, a hand pump we used for oil drums. Then I raided the supply trailer for anything that looked like it could move liquid: spare fuel line, a couple valves, a pressure gauge, a coil of copper tubing meant for a heater repair.

Frankie watched, then finally said, “Okay. Say we build your miracle truck. How do we keep the fuel from freezing or sludging?”

That stopped me.

Winter fuel was touchy. Diesel especially. And gasoline got thick and stubborn when the cold was angry enough. The last thing we needed was a pump that turned into an ice sculpture.

I looked toward the bakery’s chimney. Smoke still drifted from it. Someone was burning wood inside, probably the villagers trying to stay alive.

“Heat,” I said.

Frankie snorted. “You gonna hug the barrels?”

“No,” I said, and my eyes landed on the copper tubing coil. “We run a line from the engine’s coolant system through a coil around the fuel line—like a poor man’s heater. Keep the pump and the manifold warm while the engine runs.”

Frankie stared. “That’s… actually smart.”

I shrugged. “Don’t tell anyone. I’ve got a reputation.”

He laughed once, quick and sharp, then sobered. “Who’s gonna drive it?”

I looked at him. “You.”

Frankie’s face went pale in a way that had nothing to do with snow. “Me? Why me?”

“Because you can drive anything with wheels,” I said. “And because you’re the only one who complains enough to stay awake.”

He opened his mouth to argue, then a distant crackle of machine-gun fire cut through the village like a reminder.

Frankie closed his mouth. “Fine,” he muttered. “But if this thing explodes, I’m haunting you.”

We worked like we were racing a clock we couldn’t see.

First, we got the truck running. The radiator crack got patched with solder and a prayer. I used a strip of rubber and clamps to seal what I could. Frankie and I swapped in a spare fan belt from a wrecked Opel we found in a ditch. The engine sputtered, coughed, then caught, rattling like an old man laughing.

It wasn’t pretty, but it lived.

Then we needed tanks—fuel storage.

The motor pool had two 55-gallon drums of gasoline and one drum of something labeled in a language none of us could read. We didn’t touch the mystery drum. In war, you learn quickly that unknown liquids aren’t your friends.

Elsie Marston helped us roll the gasoline drums into the workshop. She was a corporal in the motor pool, and her hair was tucked under a cap with a grease stain like a badge.

“You boys building a circus?” she asked, watching Frankie wrestle a drum.

“Building a lifeline,” I said.

Elsie’s eyes narrowed. “Is this the part where you tell me the plan?”

I pointed at the truck. “We make it a refuel rig. Pump, manifold, multiple hoses. Pull up beside a tank, fill it fast, move to the next. Keep the column moving.”

Elsie walked around the truck, tapping the bed, the frame, the drums. “You’re gonna mount those?”

“Strap them,” I said. “Chains. Brackets if we have time.”

“And the pump?” she asked.

I held up the hand pump. It looked pathetic in my hand—like trying to fight a bear with a spoon.

Elsie stared at it. “That’s a joke.”

“It’s a start,” I said.

She made a sound like disgust and walked out. I thought she’d decided we were idiots.

Ten minutes later she returned dragging a small rotary pump unit—the kind used for field fueling—covered in mud and wrapped in a tarp.

“Found it in a wrecked supply trailer,” she said. “Still works. Needs a new gasket.”

I blinked. “Elsie, you’re an angel.”

She snorted. “I’m a motor sergeant with eyes. If your plan works, I don’t die freezing in a ditch because some lieutenant thought ‘logistics’ was a fancy word.”

We rebuilt the pump on a workbench while the village outside held its breath. I cut a gasket from spare rubber. Frankie wired the pump to the truck’s electrical system, hands shaking but steady enough to do the job.

Then came the manifold: a distribution line with valves so we could run multiple hoses. I scavenged brass fittings from smashed British kit. I used pipe segments and clamps. Elsie found a pressure relief valve that might have belonged to a coffee machine for all we knew, but it threaded right.

When we bolted the pump and manifold to a steel plate and mounted it on the truck bed, it looked like a monster cobbled together from junk and determination.

Frankie leaned back, wiping his brow. His breath made clouds. “We’re gonna get court-martialed for this, right?”

I looked at the rig. “Only if we survive long enough for paperwork.”

Outside, the light was dimming. The snow came harder, thick and relentless. Somewhere beyond the trees, artillery murmured like thunder.

Elsie climbed into the truck bed and tugged the chains holding the drums. “If this breaks loose on a bump, it’ll kill us,” she said.

“It won’t,” I said.

“How do you know?” she demanded.

I tightened the chain until my fingers went numb. “Because I need it not to.”

That wasn’t engineering. That was faith wearing grease-stained gloves.

We tested the rig with a small jerry can first.

I flipped the pump switch. The motor whined. The hose trembled, then liquid surged through, spilling into the can with a satisfying glug.

Frankie let out a breath like he’d been holding it since Pearl Harbor. “It works,” he said, almost reverent.

“It works,” I echoed.

The next test was heat. We ran the engine and tapped into the coolant line, routing it through the copper coil wrapped around the main fuel line near the pump. It wasn’t elegant, but after ten minutes, the fittings weren’t icing over.

Elsie touched the line and nodded. “Warm enough,” she said. “Not hot. But not frozen.”

The final test was speed.

We pulled the truck beside a Sherman that had limped into the village on fumes. Its crew watched us with the kind of attention you give a surgeon holding a scalpel.

Lieutenant Hayes appeared again, eyes bloodshot.

“What is that?” he demanded.

“Your tanks’ next heartbeat,” I said.

He stared at the drums. “Is that safe?”

“No,” I said honestly. “But neither is sitting here.”

Hayes’s mouth tightened. Then he nodded once. “Do it.”

Frankie climbed into the cab, engine rumbling. Elsie and I worked the hoses, snapped the nozzle into the Sherman’s fuel port, opened the valve.

The pump kicked on. Gasoline rushed. The gauge climbed.

The tank crew’s faces changed—skepticism sliding into something that looked like hope.

“How long?” the crew chief asked.

I watched the gauge, did the math in my head. “Five minutes,” I said. “Maybe less.”

The crew chief stared. “We usually take twenty with cans.”

I didn’t look away from the needle. “Then today we don’t.”

Four minutes and forty seconds later, I closed the valve and snapped the nozzle off. The Sherman’s engine coughed, then roared alive like it had been woken from a nightmare.

The crew cheered. Not loud—nothing loud in war—but the sound was there, raw and grateful.

Hayes looked at me with something like disbelief. “How many can you hit?” he asked.

“As many as we have fuel for,” I said.

He glanced at the road east, where the dusk was sinking. “Then you’re coming with us.”

That wasn’t a request.

Frankie’s eyes widened. “With them?”

“With the column,” Hayes said. “We take the crossroads. We keep moving.”

Elsie hopped down from the truck bed and wiped her hands. “If this thing saves your hide, Lieutenant,” she said, “you owe me a steak.”

Hayes blinked like he wasn’t sure what a steak was anymore. Then, quietly, “Deal.”

We rolled out as night fully settled.

The refuel truck sat in the middle of the armored column like a nervous kid walking between bullies. Shermans rumbled around us. Half-tracks crawled behind. Infantry trudged along the ditches, silhouettes against the snow.

Frankie drove with both hands locked on the wheel, jaw clenched. He kept muttering, “Just a delivery route. Just a delivery route,” like if he said it enough, Brooklyn would appear in front of him.

I rode shotgun, map on my knees, flashlight tucked under my chin. Elsie sat in the back with the pump rig, checking hoses, tightening clamps. The pump’s whine had become a comfort, like a heartbeat you could hear.

We didn’t have headlights. Too risky. We followed the tank taillights, dim slits of red, like embers in a blizzard.

At the first stop, one Sherman had thrown a track. The crew was working fast, hands bare despite the cold because gloves made you clumsy. Hayes waved us in.

“Fuel first,” he said. “Then we fix the cripple.”

I jumped down, hose in hand, and ran beside the tank like I’d done it all my life. Open valve. Pump on. Watch gauge. Shut valve. Move.

The rhythm became everything.

Refuel. Move.

Refuel. Move.

Refuel. Move.

Each time the truck pulled up, each time a tank drank, the column stayed alive.

Somewhere out in the trees, a German flare went up—white light hanging in the air, turning snow into glitter. Everyone froze. Engines idled low.

Hayes hissed, “Hold.”

We held. My heart hammered. Frankie’s knuckles were white on the wheel. Elsie’s hand rested on the pump switch like it was a trigger.

The flare faded. Darkness returned like a blanket.

“Move,” Hayes whispered.

We moved.

The crossroads was a black X carved into the forest. A small farmhouse sat nearby, its windows dark. The road signs were riddled with bullet holes. The snow was churned up by tracks and boots.

Hayes’s lead tank crept forward, turret scanning.

Then came the crack of a shot—sharp, close.

A tracer streaked across the road, bright as a comet.

“Contact!” someone shouted.

The lead Sherman fired, the muzzle flash a sudden sun that lit the trees. The blast thumped in my chest. Snow shook from branches like shaken sheets.

I couldn’t see much—just shapes and light and the sense of danger closing in. I heard the whine of an engine, German maybe, and the clatter of machine-gun fire.

Frankie yelled, “Ben! Ben, what do we do?”

I ducked instinctively, though the cab wouldn’t stop much. “Stay behind the tanks!” I shouted.

A round pinged off something nearby—metal ringing like a bell. Frankie flinched.

Hayes’s voice came over the radio, tight and controlled. “Rojas, stay put. Do not drive into the intersection.”

“Copy,” I said, though nobody asked me.

We sat there while the fight happened around us—brief but violent, like a fistfight in the dark. The Germans weren’t a full force, just a probing patrol, maybe armored cars, maybe a light tank. They’d expected to find an easy road, not a wall of American steel.

After ten minutes, it was over. The gunfire faded. The world went quiet except for engines and the wind.

Hayes appeared beside the truck, face smeared with grime, eyes bright with adrenaline.

“You did it,” he said.

I blinked. “I didn’t shoot anything.”

He shook his head. “We’d have been dead in the village. We’d have never gotten here. You kept the column moving.”

Behind him, the Shermans sat at the crossroads like guard dogs. Infantry poured into the ditches, setting up positions. Someone dragged a German prisoner past, head down, boots slipping in snow.

Elsie climbed out of the back, flexing her fingers. “How much fuel we got left?” she asked.

I checked the drum levels. “Not much,” I said. “But enough for the next push if we’re careful.”

Hayes looked at the refuel truck like it was a miracle he didn’t deserve. “They’ll send more fuel once they know we’re here,” he said, more to himself than to me.

I didn’t argue. In war, “they’ll send more” was both a promise and a prayer.

Frankie leaned his head against the steering wheel and whispered, “I can’t feel my feet.”

“Congratulations,” Elsie said. “That means you’re alive.”

We held that crossroads through the night.

The Germans tried a few times—small bursts of fire, an engine noise in the trees, a distant thump. Each time the American line answered with steel and stubbornness.

I spent most of it with the refuel truck, checking hoses, listening for leaks, keeping the pump warm. A fuel leak in a firefight is a nightmare you don’t wake from. I ran my hands along the fittings every hour, feeling for wetness, smelling for gas through the cold.

At dawn, the snow eased. The sky turned pale, a thin light that made the world look exhausted.

A supply convoy finally arrived—proper fuel trucks with proper markings, escorted by MPs who looked relieved to find someone who knew where the front line actually was.

The lead driver climbed down and stared at our rig.

“What the hell is that?” he asked.

Frankie sat on the hood, chewing something that might have once been gum. He said, “That’s the reason you ain’t explaining to your grandkids why you got lost.”

The driver blinked. “You built it?”

I looked at the truck, at the drums strapped down, at the manifold held together by clamps and pure spite. “We borrowed parts from the universe,” I said.

The driver laughed, shaking his head. “Never seen anything like it.”

Hayes came over, looking like he’d aged a year overnight, but his eyes were steady.

“Rojas,” he said, “battalion’s pushing again in an hour. They want your truck up front until the supply lines catch up.”

I opened my mouth to say no—because the truck was a death trap, because Frankie deserved a warm bed, because my hands were cracked and bleeding under the gloves.

Then I thought of the tanks in the ditch. Thought of the fuel gauge needle sitting on empty like a verdict.

I nodded. “Yes, sir.”

Elsie groaned. “I hate you.”

Frankie lifted two fingers in a lazy salute. “Delivery route,” he muttered. “Just a delivery route.”

We ran that refuel truck for eleven more days.

We refueled tanks in forests, in ruined towns, in open fields where the wind cut straight through you. We refueled under shell bursts that shook the hoses. We refueled in silence and refueled while men shouted, while medics dragged stretchers past, while snow melted on hot engine decks and turned into steam.

Sometimes the truck was the only reason a platoon moved at all. Sometimes we’d roll up to a line of Shermans with crews staring at us like we were bringing water to a desert.

I never pretended it was glamorous.

It was cold. It was dirty. It was terrifying in a quiet way—because the enemy didn’t have to kill you with bullets if you ran out of fuel in the wrong place.

By the time the weather broke and the German push started to collapse, the refuel truck had become a legend in the unit. Men patted the side panels like it was a lucky dog. Someone painted a name on the cab in white letters:

THE GUTS WAGON

Frankie claimed he hated it.

He also drove it like it was his firstborn.

Near the end of January, when the lines stabilized and real supply trucks could finally breathe again, Hayes pulled me aside.

His face was softer now, the sharp edges worn down by survival.

“You know,” he said, “back home, people think wars are won by the guys who shoot.”

I shrugged. “Shooting helps.”

He nodded, then glanced at the refuel truck parked nearby, its bed still stained with oil and snowmelt.

“But nobody tells stories about the fuel,” he said. “Nobody tells stories about the man who makes sure the tank can move.”

I looked at my hands. Grease under the nails. Knuckles scarred. Skin cracked from cold and work.

“Maybe they should,” I said.

Hayes held out his hand. I shook it.

“Thank you,” he said simply.

I didn’t know how to answer that, because it felt too big for the words we had. So I did what mechanics do when emotions get too close.

I nodded once and went back to the truck.

Years later, after the war, when the world tried to pretend it had always been peaceful, I opened a small garage on a two-lane road outside Toledo. The sign said ROJAS SERVICE in red letters that faded in the sun.

Men came in with rattling engines and leaky radiators. They complained about prices, about weather, about their wives. They drank coffee and told jokes and acted like nothing terrible had ever happened.

Sometimes, on cold mornings, when the wind came in off the fields and the shop smelled like oil and metal, I’d hear the faint whine of a pump in my memory.

I’d see snow falling sideways. I’d see a line of tanks with empty stomachs. I’d see Frankie’s white knuckles on the steering wheel. Elsie’s grim grin as she tightened a clamp. Hayes’s eyes when the fuel finally hit the gauge.

And I’d remember the lesson the war taught me, the one nobody puts on medals:

Big machines don’t win battles by themselves.

They win because someone—some tired, stubborn mechanic—refuses to let them stop moving.

And sometimes, in the middle of a frozen forest, that’s the difference between getting home and becoming part of the snow.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.