“They Refused to Go Home” — The Untold Night German POWs Chose Australia Over a Ruined Homeland, and the Promise They Made to Stay. NU

“They Refused to Go Home” — The Untold Night German POWs Chose Australia Over a Ruined Homeland, and the Promise They Made to Stay

The first time I heard a German prisoner say he didn’t want to leave Australia, I thought it was a trick.

It was late afternoon, the kind where the heat loosens its grip but doesn’t quite let go. Dust hung over the camp road in a thin, glowing sheet, and the gum trees beyond the wire looked calm enough to make you forget what year it was and what the newspapers kept printing in bold type.

I was walking the perimeter with a clipboard under my arm—paperwork, always paperwork—when a voice called out from the shade of a corrugated hut.

“Mr. Hale!”

Not “Guard.” Not “Sergeant.” Not even “Hey you.” Just “Mr. Hale,” like I was a teacher and he was staying after class.

I stopped and looked through the double fence. The man was tall and narrow, with the kind of cheekbones that made you think he’d been carved from driftwood. He wore the same faded camp uniform as the others, but he carried himself like it was still pressed. His hair had gone lighter in the sun, and his forearms were brown from months of farm work under Australian skies.

His name, according to my files, was Kurt Vogel, captured in North Africa and shipped halfway around the world because our side had more ocean than Germany had luck. He’d been an engine-room man on a supply ship—no swastika speeches, no fanatical shine in his eyes when he spoke. Just a mechanic who’d been swept into war like a bolt into a gearbox.

“What is it, Vogel?” I asked.

He smiled faintly, then glanced behind him. A few other prisoners were pretending not to listen, pretending not to be curious. In a camp, privacy was the rarest currency.

“I have a question,” he said carefully, in English that had improved faster than I liked to admit.

“If it’s about extra bread, the answer is no.”

“It is not about bread,” he said. “It is about going home.”

The word home landed between us like a stone. For the guards, home was a town with a pub and a front porch and people you were fighting to keep safe. For the prisoners, home was… complicated. We’d learned that much.

I tried to keep my voice flat. “You’ll go when your government takes you back. When the shipping comes. When the lists are made.”

He nodded like he’d expected that answer. “Yes. But… when it is time.” He took a breath. “If I refuse?”

I actually laughed, once, short and surprised. “You can’t refuse repatriation.”

His face didn’t change. “But what if I do?”

The sun slipped behind a cloud, and the camp looked suddenly grayer, as if the sky itself had decided to listen.

“Why would you?” I asked, and regretted it as soon as it left my mouth. Curiosity was dangerous in wartime. Curiosity made you see men instead of uniforms.

Kurt Vogel folded his hands like he was steadying something inside himself. “Because I do not think there is anything for me there anymore,” he said. “And because… I think there is something for me here.”

I looked past him, beyond the huts and the small garden patches the prisoners had coaxed into life, beyond the clotheslines strung like surrender flags. Australia stretched out in every direction—hard, bright, stubborn country that didn’t care where you’d been born.

“Something for you here,” I repeated.

He nodded. “A chance.”

I didn’t answer. I couldn’t. I was a clerk-sergeant in a camp the papers barely mentioned, but I still represented a country at war. If I said the wrong thing, it could turn into rumor, then scandal, then a letter from headquarters with my name underlined.

So I did the sensible thing: I wrote nothing down and walked away.

But the question followed me.

It followed me to the mess hall that smelled like boiled cabbage. It followed me to the administration hut where typewriters clacked like nervous teeth. It followed me into the night, when the camp quieted and you could hear the wind moving through the wire like a slow, metallic sigh.

And it followed me into the year when the war finally ended.

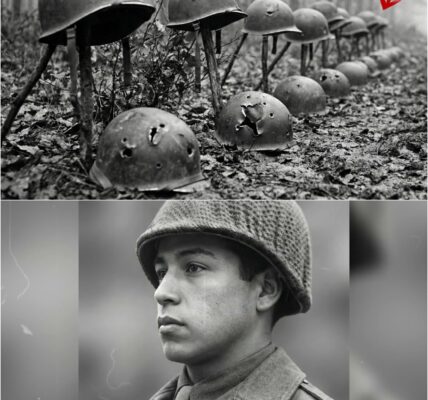

When Germany surrendered, the camp didn’t explode into celebration the way I’d expected. There were cheers in town, sure—flags, beer, people hugging strangers in the street like the world had been returned to them. But inside the wire, the Germans mostly went quiet.

They stood in small groups, reading the posted notices until the paper curled in the sun. Some sat on their bunks with their faces in their hands. A few wrote letters in furious bursts, as if speed could outrun grief.

I remember thinking: They look like men who’ve been told their house burned down while they were away.

In the months after victory, new words entered our daily language: repatriation, processing, shipping schedules, displaced persons. Officers flew in from Canberra and walked through the camp with clipboards and polished shoes. Red Cross men arrived with kind eyes and tired mouths. The prisoners were asked questions—names, ranks, hometowns—that suddenly mattered in a different way.

And then, one morning, the lists went up.

Men crowded the notice board like it was a lifeline. Names in neat columns. Dates. A port. A ship.

I watched faces change as they found themselves—relief in some, dread in others. One man kissed the paper like it was a prayer. Another stared so hard his eyes went watery, then turned and walked away as if the board had slapped him.

Kurt Vogel didn’t push forward. He waited back, arms crossed, watching the crowd as if he already knew what the paper would say.

When the men thinned out, he stepped up, scanned the list, and nodded once. He was on it.

He didn’t look relieved.

That evening, as I was closing the office, I found him waiting by the fence line where we’d spoken months ago. Same shade, same dust, same quiet stubbornness in his posture.

“Mr. Hale,” he said.

“What do you want, Vogel?”

He held something out through the inner fence: a folded sheet of paper, edges soft from being handled too much.

“A petition,” he said.

I didn’t take it. “A petition for what?”

“For permission to remain in Australia.”

The words sounded absurd, like asking permission to stay on the moon.

I stared at him. “You can’t just—”

“It is signed,” he said, cutting in gently. “Not only by me.”

Behind him, other men had drifted closer, not crowding, not threatening—just present. Like witnesses in a courtroom.

“How many?” I asked.

Kurt glanced back. “Twenty-three.”

Twenty-three men who had been enemies, who had worn gray uniforms on the other side of the world, now asking to stay in a country that had built barbed wire to keep them contained.

I finally took the paper.

Names marched across it in careful ink. Some were neat, like a schoolmaster’s. Some were jagged, like hands that shook. At the bottom, someone had added a line in English: WE ASK TO STAY AND WORK. WE DO NOT ASK TO BE FORGIVEN. ONLY TO LIVE.

My throat tightened in a way I didn’t like.

“Why?” I asked again, softer this time. “Tell me why, and don’t give me poetry.”

Kurt exhaled, as if he’d been holding his breath since 1939.

“Because Germany is broken,” he said. “Because there is no work, no food, no roofs. Because some of us—” He swallowed. “—some of us do not know if our families are alive. And some of us know they are not.”

A man behind him muttered something in German, sharp and bitter. Kurt didn’t turn.

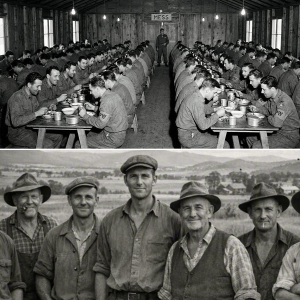

“And because,” Kurt continued, “we have worked here. On farms. In orchards. We have seen what a normal day can look like. We have been treated…” He searched for the word. “Not kindly, always. But fairly.”

Fairly.

That word did more damage to my defenses than any accusation could’ve.

I thought of the farmers who’d driven up in trucks to collect labor crews—men who’d lost sons in the war but still nodded at the prisoners with stiff civility because a crop didn’t care about grief. I thought of the prisoner gardens, the makeshift soccer games, the books passed around until their spines cracked. I thought of how, in the middle of a war, routine had been the one mercy both sides could afford.

Kurt’s eyes held mine through the wire. “And some of us,” he added quietly, “have met people.”

I understood immediately, even before he explained. I’d seen it happen in small ways—letters exchanged through legal channels, shy conversations at farm gates, a German prisoner looking too long at a woman handing him water. You couldn’t put fences around loneliness. You could only pretend you had.

“You mean you fell in love,” I said.

He didn’t flinch. “Yes.”

It shouldn’t have surprised me, but it did anyway. War trained you to imagine enemies as shapes on a map. Love insisted on faces.

“Who?” I asked before I could stop myself.

Kurt hesitated, then said, “Her name is Evelyn Mercer. Her father has an orchard near Benalla. I have worked there.”

I knew the orchard. I’d done paperwork for that farm detail. Evelyn Mercer was the farmer’s daughter with the calm eyes and the quick hands. She’d waved once at the truck as it took the prisoners away, like she was saying goodbye to workers, not captives.

“Does she know you’re doing this?” I asked.

Kurt nodded. “She said, ‘If you are sent away, I will not pretend it did not happen.’”

That sounded like an Australian woman to me—plainspoken, brave in the way that didn’t announce itself.

I looked down at the petition again, at the names, at the blunt English at the bottom.

“You realize,” I said, “there are people here who will never accept you.”

Kurt’s mouth twitched. “There are people in Germany who will never accept me either.”

That was the moment I saw the other truth hiding behind his words: this wasn’t only about survival or love or work.

It was about shame.

Not just the shame of losing, but the shame of belonging to something that had poisoned the world. Even men who claimed they were “only mechanics” carried that weight in the way they stared at the ground when the newsreels played.

“Some of us,” Kurt said, as if reading my thoughts, “do not want to go back and become… ghosts among ruins. We want to build something that is not made of hate.”

The wind shifted. Somewhere in the camp, a harmonica started playing—one thin melody that sounded like it had traveled a long way to get here.

I should’ve handed the petition back and told him to forget it. Regulations. Process. Orders.

Instead, I asked, “What do you think happens if you refuse to board the ship?”

Kurt’s gaze didn’t waver. “Perhaps you put me in chains. Perhaps you force me. Perhaps you put me on the ship anyway.” He shrugged. “But I think… there is a way for this to be done without more war.”

I wanted to tell him he was naive. That nations didn’t bend because a handful of men wanted a second chance.

But the world had already bent in stranger ways. I’d seen boys become soldiers and then become graves. I’d seen enemies become prisoners and then become farmhands. I’d seen a continent on the far side of the earth hold men from another continent behind wire, and somehow—somehow—turn that into something that didn’t end in blood.

Not always. There had been camps where violence erupted, men who couldn’t let the war go even after it was over. I’d read reports. I’d seen the aftermath in photographs I wished I hadn’t looked at.

But in our camp, for reasons I still can’t fully explain, something quieter had taken root.

Maybe it was distance. Australia was so far from Europe that the war felt like weather—real, deadly, but not personal in the same way it was in London or Berlin. Maybe it was the land itself, too big and too blunt for old grudges to survive.

Or maybe it was this: people here understood hard times. Drought. Flood. Fire. They understood that survival wasn’t moral or immoral; it just was. And sometimes, if a man showed up willing to work and keep his head down, you let him.

I folded the petition and slipped it into my clipboard.

“I can’t promise anything,” I said.

Kurt nodded like he’d expected nothing else. “But you will give it to someone who can.”

“I’ll pass it up the chain,” I said, and heard how official it sounded, how cowardly.

Kurt’s shoulders lowered a fraction. Relief, but cautious—like a man seeing rain clouds after a drought, still afraid the wind will blow them away.

As I turned to leave, he said, “Mr. Hale?”

I stopped.

“In the radio room,” he said, “we sometimes heard speeches from Germany. They said we were fighting for a thousand years.” His voice grew tight. “Now I think we were fighting for nothing. But here—” He gestured toward the darkening horizon, the gum trees, the open land beyond the fences. “Here I have learned I can be only a man. That is all I want.”

I walked back to the office with the petition heavy under my arm.

That night, I wrote a report that was half regulation and half confession. I chose my words carefully—requests for residency, willingness to work, good conduct, skills useful to agriculture, no evidence of extremist affiliation—the kind of language governments could digest without choking on emotion.

I sent it up.

And then I waited, not in the passive way people wait for trains, but in the tense way you wait when you’ve stepped onto a bridge you can’t see the end of.

Weeks passed. Then months.

Ships came and went. Many Germans left. Some went eagerly, clinging to the idea that “home” could still be found like an address. Some went with hollow eyes, like men walking into fog.

But not all.

Not Kurt Vogel and his twenty-three.

Their case, I learned later, wasn’t unique. Across Australia, small numbers of German and other European POWs—especially those who had worked on farms, who had formed relationships, who feared returning to shattered cities—made similar requests through proper channels. Governments argued. Newspapers muttered. Letters arrived at offices with opinions written in angry ink.

And still, slowly, the world shifted again.

The first official response came in the form of a visiting officer with a sunburned nose and a file folder thick as a Bible.

“They can apply,” he told me, like he was granting a favor to an insect. “Individually. Background checks. Sponsorship. Employment arranged. No guarantees.”

No guarantees. But it wasn’t a no.

When I told Kurt, he sat down on the step outside his hut as if his legs had finally remembered they were allowed to rest.

He didn’t smile right away. He stared at the dirt, then at his hands, then up at the Australian sky.

“Thank you,” he said, and his voice cracked on the second word.

I cleared my throat. “Don’t thank me yet. It’s paperwork and waiting and more waiting.”

He nodded. “I know waiting.”

Over the next year, I watched those men turn into something the war had not planned for.

They went from prisoners to applicants. From numbered uniforms to borrowed shirts on work details. They sat with officers and answered questions about their past, their politics, their units, their beliefs. Some were rejected and shipped out anyway, angry and heartbroken. Some withdrew their requests, choosing the certainty of leaving over the slow torture of hope.

But a handful—Kurt among them—made it through the narrow gate of permission.

The day Kurt left the camp, it wasn’t in a guarded truck.

It was on the back of a farmer’s utility vehicle, his small suitcase wedged beside a crate of apples. He wore civilian clothes that didn’t quite fit and boots that looked too new, like the war had finally ended just for him.

I met him at the gate with the last papers. He signed where the ink demanded. His hand shook once, then steadied.

Evelyn Mercer stood a few steps behind him, sun in her hair, her expression set like she’d decided something and would not un-decide it. She didn’t touch him—not yet—maybe because a lifetime of rules still hovered in the air. But her presence said enough.

Kurt looked at me, then at the camp behind him—the wire, the huts, the guards, the place that had been his world in captivity and, strangely, the birthplace of his second life.

“I will not forget,” he said.

“Don’t get sentimental,” I told him, because I didn’t know how to handle gratitude from a former enemy.

He gave that faint smile again. “I will try.”

Then he climbed onto the vehicle. Evelyn took the driver’s seat. The engine coughed once, then caught.

As they rolled forward, Kurt turned and lifted a hand—not in salute, not in surrender, but in something simpler: goodbye.

The gate closed behind them with a soft metallic click.

For a long moment, I stood there staring at the empty road, listening to the wind in the trees and the distant sound of farm life—birds, an engine, a dog barking like it had always barked, even during war.

I thought of the phrase he’d used months earlier: a chance.

That was the real shock of it, I realized. Not that men had refused to go home.

But that, after everything—after uniforms and bombs and orders and graves—somewhere on the far edge of the world, a handful of men had looked at the ruins behind them and the hard sunlight ahead and decided they wanted to try being human again.

Years later, long after I’d left the service, I drove past an orchard near Benalla and saw a man on a ladder picking fruit with practiced ease. He was older, broader now, sunburned like any Australian farmer. A woman stood below, handing up a basket, laughing at something he’d said.

When he climbed down, he wiped his hands on his trousers and glanced toward the road. For a second, our eyes met.

He didn’t wave.

He didn’t have to.

Because the war was finally, fully behind him—and he had stayed.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.