- Homepage

- Uncategorized

- They Mocked His “Backwards” Loading Method — Until His Sherman Destroyed 4 Panzers in 6 Minutes. VD

They Mocked His “Backwards” Loading Method — Until His Sherman Destroyed 4 Panzers in 6 Minutes. VD

They Mocked His “Backwards” Loading Method — Until His Sherman Destroyed 4 Panzers in 6 Minutes

The Backward Method: A Soldier’s Innovation That Saved Lives

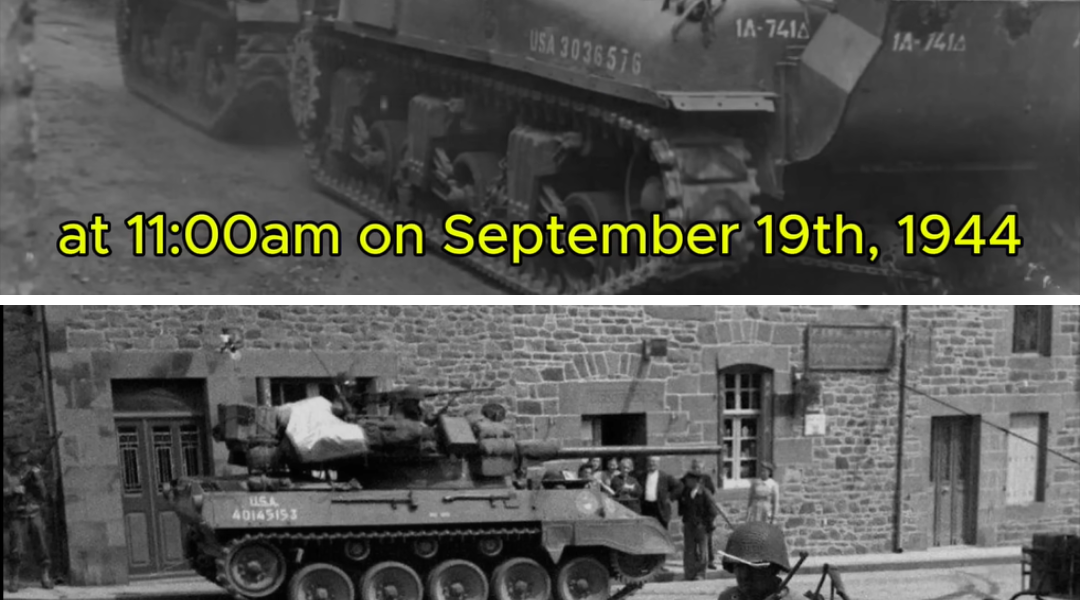

September 19th, 1944 – 11:23 a.m. – Somewhere near Araort, France. The roar of battle echoed in the distance, but inside the cramped turret of the M4 Sherman tank Hell’s Fury, Private First Class Walter Kowalski was focused on one thing—survival. The tank’s hull vibrated with every passing moment, the tension thick as the German Panzer IV tanks moved in for the kill. Walter’s heart pounded in his chest as he grabbed the first shell from the ready rack—38 pounds of high explosive.

His hands were slick with sweat and oil, his mind racing. He had never been trained to load a real round in combat. Walter was a mechanic, not a gunner. Just two days earlier, the crew had lost their previous loader when a Panzer shell pierced their turret. Now, Walter was a replacement, his hands shaking with uncertainty. He had loaded exactly four training rounds in his life before this moment.

The crew was frantic. The gunner was shouting something about traverse speed. The commander was barking coordinates. The driver was desperately reversing into a hedge row, trying to make the tank less of a target. And Walter—he was supposed to load the 75mm shell into the breach as quickly as possible.

Standard training had drilled him in the method: face the breach head-on, grip the shell firmly, and ram it home. But Walter was left-handed, and the Sherman turret was cramped. His left elbow slammed into the gunner’s shoulder every time he turned to face the breach. The gunner shoved him hard, and the shell almost slipped from his hand. The commander’s voice came, sharp and desperate: “Hurry up, Kowalski! They’re getting closer!”

Panic set in. The Panzers were at 800 yards. Walter did the unthinkable. He turned his back to the breach. He reached behind himself, felt for the opening with his left hand, and guided the shell into the chamber. He used his body weight to ram it home, feeling the mechanics of the tank as though it was an extension of his own body.

The moment the breach closed, the gunner fired, and the recoil of the 75mm cannon blasted through the turret, searing the back of Walter’s neck. But Walter didn’t flinch. He was already reaching for the next round. In a swift, practiced motion, he repeated the process—turning his back, guiding the shell, and ramming it home.

The tank shuddered with each shot. Three seconds. Four seconds. Each time faster. The Panzers were getting closer, but Walter didn’t slow down. His body was screaming from the effort, but he kept loading, firing, reloading.

By the time the firing stopped, four German tanks were burning in a field 400 yards away. Walter stood, exhausted but still steady. The gunner was staring at him, and the commander climbed down from his hatch, his face one of astonishment.

“Private Kowalski,” the commander asked slowly, “how fast was that?”

Walter didn’t know. The gunner had been counting. “Three seconds per round, sometimes less,” he said, his voice calm despite the chaos that had just unfolded.

The commander stared at him, speechless. No one in the army had ever loaded a 75mm cannon like that—backward, against all the training manuals and safety procedures. But it had worked.

From that moment, Walter Kowalski’s method would change the course of tank combat in World War II.

Walter had been thrust into the chaos of battle with little more than a mechanic’s training, but his instincts were sharp. He quickly realized that the M4 Sherman tank wasn’t built for a head-to-head fight with the German Panzers. The Sherman’s 75mm cannon had its limitations, especially when facing the well-armored Panzer IVs. But Walter understood the value of speed. He knew that in battle, every second counted. And with his left-handed technique, he was able to load and fire faster than anyone else in the unit.

By the time of the engagement on September 19th, 1944, Walter’s crew had already lost 18 Shermans in two days of fighting. The Germans were relentless, their Panzer tanks picking off American crews with devastating precision. The Sherman’s armor was thinner than that of the German tanks, and its 75mm cannon couldn’t penetrate the front armor of the more advanced Panzer models.

But Walter’s innovation turned the tables. By loading faster than any of the other crews, he gave Hell’s Fury a chance to survive. He was able to fire off rounds quicker than the Panzers could react. His method didn’t just save his crew—it allowed them to take out multiple German tanks in minutes. Four kills in six minutes. A flawless performance that defied every tank manual written up until that point.

The next few days saw the spread of Walter’s backward loading method. Tank commanders, desperate for an edge, watched in disbelief as more and more loaders began to adopt the technique. In an army where rules and regulations governed everything, Walter’s method broke every safety protocol. But the results were undeniable. It worked.

The higher-ups began to notice. Lieutenant Colonel Kraton Abrams, the commander of the 37th Tank Battalion, had built his reputation on aggressive tactics. When he saw a loader using Walter’s method, he didn’t waste time questioning it. He saw the speed and the precision. He saw the results.

By October 1944, the technique had spread throughout the 37th Battalion. Tank commanders didn’t care about regulations. They cared about survival. Walter’s method was faster, more efficient, and it saved lives. The kill ratio improved. Sherman crews were taking out German tanks before they even had a chance to fire back.

Soon, General George Patton himself took notice. He wasn’t one for bureaucracy or red tape—he cared about results. And when he saw how the backward loading method was improving kill ratios and survival rates, he made it official. All tank battalions in the Third Army would adopt the technique immediately.

It wasn’t long before the method spread throughout the entire European theater. Tank crews were trained on it in combat, often learning it through whispered conversations in the maintenance sheds. By the time the war ended, the backward loading method had become standard practice for tank loaders across the army.

But despite his pivotal role in the success of the Third Army, Walter never sought recognition. He didn’t want medals or accolades. To him, it was just about surviving—doing whatever it took to make sure he and his crew made it home.

When the war ended, Walter returned to Detroit, where he went back to his job as a mechanic at the Ford River Rouge plant. He married, had children, and lived a quiet life. He rarely spoke about his time in the war, and when journalists tracked him down in the 1960s to ask about his innovative loading method, he simply shrugged it off.

“It wasn’t anything special,” he said. “Just something I figured out when my shoulder was hurt.”

But for the men who served with him, Walter Kowalski was more than just a mechanic. He was a hero. The technique he developed saved countless lives, and in the years that followed, it became a standard practice in tank warfare. Even in the Korean War, where the Sherman tanks were used against North Korean T-34s, the method proved its worth.

In the end, Walter Kowalski’s name wasn’t recorded in history books as the man who revolutionized tank warfare. His obituary mentioned his service in World War II, but it didn’t mention the thousands of lives his simple innovation saved. It didn’t mention the countless tank crews who survived because of him. But the men who knew him—the ones who learned from him—would never forget.

Walter passed away in 2004, at the age of 82, and was buried in Resurrection Cemetery in Clinton Township, Michigan. His funeral was a quiet affair, attended by his family and a few old war buddies. But they knew the truth—Walter Kowalski had changed the course of the war. He had saved lives and made sure that when a soldier was facing down death, he had a better chance of survival.

And that was all that mattered to him.

His legacy lived on in every loader who adopted his method. It spread to every corner of the globe where tanks fought battles. In Korea, Vietnam, and beyond, Walter’s technique remained relevant—proof that sometimes the most important innovations come from the soldiers on the front lines, the ones who think outside the box and break the rules when they don’t work.

For Walter Kowalski, it wasn’t about following orders—it was about saving lives. And that’s the kind of heroism that deserves to be remembered.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.