They Called This B-17 “Cursed” — Until One Crew Destroyed 17 Japanese Zeros Alone

At 8:03 a.m. on June 16th, 1943, Captain Jay Zeamer held his B17 steady at 25,000 ft over Bua Island as 16 Japanese Zero fighters climbed toward him from the airirstrip below. The 24year-old pilot had rebuilt this bomber from the boneyard 3 months earlier with a crew nobody else wanted. And today mark their most dangerous volunteer mission yet.

a solo 12,200-mile photo reconnaissance run that command had called suicidal. In the past 6 months, the Pacific theater had lost 43 unescorted bombers over Japanese-held islands with survival rates below 30%. Old 666 carried nine men that morning. Zemer’s crew called themselves the Eager Beavers because they volunteered for every mission others refused.

They taken a damaged B17E that pilots considered cursed, stripped 2,000 lb of weight, installed new engines, and mounted 1950 caliber machine guns. The bomber now carried more firepower than any aircraft in the Pacific. But firepower meant nothing against impossible odds. 16 Japanese fighters were climbing at 3,000 ft per minute.

The photo mapping run required old 666 to hold course for two more minutes. No evasive maneuvers. Nine Americans 600 m from friendly airspace. Second Lieutenant Joseph Sarnoski crouched at the bombader position in the nose. The 28-year-old had spent 18 months in the Pacific theater flying combat missions. He’d earned the Silver Star 3 weeks earlier.

His orders home were effective in 3 days. His bag sat packed at Port Moresby. He’d volunteered for this mission anyway because the crew needed an experienced bombardier to operate the cameras. The Japanese fighters reached 22,000 ft, 3,000 ft below, still climbing. Sarnoski checked his twin 50 caliber nose guns. The fixed gun that Zemer could fire from the cockpit was ready.

16 fighters against one bomber. The mission started at 4:00 a.m. when old 666 lifted off from Port Moresby, New Guinea. The Marines needed photographs of Bugenville’s western coastline for a November invasion. They needed mapping photos of Empress Augusta Bay, but intelligence added a lastminute requirement.

Photograph Buouah airfield first. The small island showed increased Japanese activity. One bomber solo, no escort. The P38s didn’t have the range. They arrived over Buganville too early. No sunlight for mapping photos. They voted wait over ocean or photograph buers reached 24,000 ft 1,000 ft below. The first five broke formation and spread out frontal attack.

Most B7s had minimal nose arament. Old 666 carried 350 caliber guns in the nose. The Japanese didn’t know that yet. Can one bomber survive 16 fighters over enemy territory? Please like to share this story. Subscribe and let’s see what happens. Back to Zemer. The 50 dove. Zemer held steady. Cameras still running. 30 seconds left.

The fighters closed at 700 mph. At 600 yards, they opened fire. Zarnoski fired back. His Twin 50s hammered. Zemer triggered the nose gun. Three guns converged on the lead zero. The engine exploded. It rolled inverted. The other four kept coming. At 300 yd, shells hit the nose. Plexiglass shattered. One shell exploded in front of Sarnoski.

The blast threw him backward. Blood poured from his neck and side. In the cockpit, shells blew holes through the floor. Zemer’s left leg erupted in pain. Shrapnel tore into both legs and wrist. The Zeros flashed past. 12 seconds. One fighter damaged, one bombader dying, one pilot wounded, 15 fighters climbing. 600 m from home.

Navigator First Lieutenant Ruby Johnston crawled forward from his position. He saw Sarnoski beneath the catwalk. Blood pulled on the metal floor. The bombader’s neck wound pumped red with each heartbeat. Johnson pressed his hand against the gash, tried to stop the bleeding. Sernowski pushed him away, pointed at the nose guns.

Another wave was coming. Johnston looked up through the shattered plexiglass. Eight more zeros were diving from 26,000 ft. They’d watched the first attack, learned from it. This time they weren’t coming five a breast. They were coming in two waves. Four from above, four from below. Bracket attack. Sarnowski dragged himself back to the bombader position.

Blood soaked his flight suit. He gripped the twin 50 caliber gun handles, swung the guns toward the incoming fighters. His hands shook. Vision blurred. He blinked. Focused. The lead zero filled his gun sight. 600 yd. 500 400 He fired. The Twin 50s roared. Tracers walked up the Zero’s nose.

The fighter’s canopy exploded. Glass and aluminum fragments spiraled away. The Zero rolled right and dove, smoking. Sarnowski shifted aim to the second fighter, fired again. Rounds punched through the engine cowling. The Zero’s propeller stopped. It fell away. In the cockpit, Zemer fought to control the aircraft.

His left rudder pedal was gone, destroyed by the 20 mm shell. Blood filled his left boot. The leg wound was deep. Bone showed through torn flight suit fabric. His right wrist bled where shrapnel had sliced through. He couldn’t feel his fingers properly. Thecontrol yoke felt slippery with blood. But he held course. The cameras were still running.

The mapping photos of Empress Augusta Bay were critical. The Marines needed them. Without these photos, the November invasion would go in blind. Men would die on beaches they couldn’t see from intelligence photos. He held steady. The four zeros attacking from below came in at 19,000 ft. Ball turret gunner staff Sergeant Forest Dilman tracked them through his gun site.

The ball turret hung beneath the B7’s fuselage. a cramped sphere of plexiglass and steel. Dilman was 5’4, small enough to fit. He’d been manning this position for 6 months, flown 32 missions, never seen an attack like this. Four fighters coming straight up from below. Most bombers couldn’t defend the belly. Old 666 could. Dilman opened fire at 400 yd.

His Twin 50s hammered. The lead zero pulled up hard, trying to break Dilman’s aim. Rounds walked up the Zero’s belly. The fuel tank erupted. Orange fireball at 18,000 ft. The other three scattered. The mapping run finished. Zemer banked left, turned southwest, heading for Buganville’s western coastline, the main objective.

13 Japanese fighters were still up there, regrouping. Sarnoski slumped over his guns. Navigator Johnston checked for pulse, found none. The bombardier had kept fighting for 4 minutes after the mortal wound. His heart had stopped. Johnston pulled the body away from the guns, took his position. Old 666 needed every gunman.

Oxygen pressure gauges in the cockpit dropped to zero. The yellow oxygen tanks behind the cockpit had exploded when the 20 mm shells hit. Every crew member now depended on small personal bottles. At 25,000 ft, those bottles lasted maybe 10 minutes. After that, hypoxia would set in. Confusion, loss of coordination, unconsciousness, death.

Zemer had a choice. Descend below 10,000 ft where men could breathe without oxygen or stay high and pass out. He chose to descend, but not yet. The cameras needed three more minutes to complete the Bugenville coastal mapping. 3 minutes at altitude without oxygen. Co-pilot, Second Lieutenant John Britain, came too.

He’d been knocked unconscious when the first shell hit the cockpit. Blood ran down the back of his head from a contusion. He looked at Zemer, saw the pilot’s left leg. The knee was destroyed, broken above and below. A hole the size of a fist gaped in the thigh. White bone fragments showed through shredded muscle. Zemer’s hands gripped the control yolk, knuckles white, face gray from blood loss. Britain reached for the controls.

Zemer shook his head. Not yet. Hold course. Two more minutes. The 13 remaining Zeros regrouped at 27,000 ft, 2,000 ft above old 666. They’d lost three aircraft, damaged two more against one bomber. The American aircraft was more heavily armed than intelligence had reported. The Japanese flight leader changed tactics.

No more frontal attacks against that nose arament. Attack from the sides, the waist positions. Most B7s in the Pacific had single guns in the waist. Easy targets. He didn’t know old 666 had twin 50s in both waist positions. Staff Sergeant George Kendrick manned the right waist gun. Sergeant Herbert Pew had the left.

Both men watched the zeros form up. Counted them. 13. Coming in from both sides simultaneously. Six from the right, seven from the left. Split attack forced the gunners to choose targets. Overwhelm one side. Kendrick and Pew had flown together for 8 months. They didn’t need to communicate. They knew the drill. Kendrick took right side threats.

Pew took left. When fighters crossed over, they’d hand off targets. The Zeros dove. Kendrick opened fire at 500 yd. His Twin 50s tracked the lead zero on the right. Tracers converged. The Zero’s wing route erupted. Fuel sprayed. The fighter rolled away. Trailing fire. Kendrick shifted to the second fighter. Fired.

Missed. The Zero was jinking. Hard to track. He led the target. Fired again. rounds walked across the Zero’s fuselage. Cockpit glass shattered. The fighter snap rolled left. Out of control. Two down on the right side. Four still coming. On the left, Pew engaged his seven targets. The first zero came in fast. Too fast.

Pew held fire. Waited. The Zero’s guns flashed. Rounds punched through old 666’s fuselage. Pew didn’t flinch. He tracked the fighter. let it fired at 300 yd. The Zero flew through his stream of fire. Engine smoking. It pulled up, disappeared above. The cameras clicked off. Mapping complete. Zemer shoved the control yolk forward.

Old 666’s nose dropped. The altimeter unwound. 24,000 22,000 20,000. The dive was steep. Necessary. The crew needed oxygen, but the Zeros were diving too, chasing. At 15,000 ft, Zemer pulled back, leveled off. The air was breathable now. Crew members gasped, sucked in oxygen. Their personal bottles had run dry minutes earlier.

Some had been close to passing out. The dive had saved them. Radio operator technical sergeant Johnny Ael climbed out of the top turret. His leftleg was bleeding. Shrapnel from the oxygen tank explosion had peppered his thigh. He ignored it, checked on the other crew. The waste gunners were still firing. The tail gunner was alive. Ball turret operational.

Navigator Johnston was manning Sarnoski’s nose guns. Sarnosowski’s body lay beneath the catwalk, covered with a jacket. Abel climbed back into the top turret, swung the twin 50s toward the pursuing Zeros. They were coming again. The Japanese fighters had old 666 at a disadvantage now. The bomber was at 15,000 ft. Lower, slower.

The zeros could dive from above with speed advantage. Eight fighters remained operational. The other five had been damaged or destroyed, but eight was still enough. The flight leader organized them into two four ship elements. One element would attack from the rear quarter, the other from the front quarter. Force the bomber to defend two directions.

Iim simultaneously. Classic Pinser. It usually worked. Tail gunner Staff Sergeant William Vaughn saw them coming. Four zeros in trail formation. Diving from his 6:00 high position, they’d approach from behind and above, attack the tail, then pull up and away before the nose guns could engage. Standard tactic. Vaughn had seen it 30 times.

He swung his twin 50s up, elevated the guns to maximum angle, waited. The Zeros opened fire at 600 yd. Too far. Rounds fell short. Vaughn held his fire. Saved ammunition. 500 yd. 400. The zeros were committed now. Couldn’t break off. Van fired. Both 50s hammered. The lead zero took hits across the engine.

Smoke poured. It pulled up hard. stalled, fell away, spinning. The other three scattered. The front element attacked simultaneously. Four zeros diving at the nose from 10:00 high. Johnston saw them, swung Sarnoski’s guns. The twin 50s were still warm from the last engagement, still loaded.

He fired at 500 yd, walked tracers toward the lead fighter. Missed. The zero was fast, closing at 400 mph. Johnston adjusted, led the target more. Fired again. Hits. The Zero’s cowling shredded. Pieces flew back. Hit the canopy. The fighter pulled up trailing smoke. Old 666 shook from hits. 20 mm shells punched through the left wing.

Hydraulic fluid sprayed. The number two engine coughed. Ran rough. Zemer checked the gauges. Oil pressure dropping. Cylinder head temperature rising. The engine was dying. He feathered the propeller, shut it down. Three engines remaining. 600 m still to go. The Japanese fighters broke off at 8:45 a.m., 42 minutes after the first attack.

They’d lost four aircraft confirmed, three more heavily damaged. Their ammunition was depleted. Fuel gauges showed critical levels. The return flight to Bua was 30 m. They couldn’t continue. The flight leader waggled his wings. the signal to disengage. Seven remaining zeros turned northeast, climbed away, left old 666 limping southwest over open ocean.

Zemer slumped in his seat. The adrenaline was fading. Pain rushed in to replace it. His left leg throbbed. Each heartbeat sent waves of agony through the shattered knee. His right wrist bled steadily. The gash was deep. He could see tendon. His flight suit was soaked red from waist to boots. Blood pulled on the cockpit floor mixed with hydraulic fluid and spent brass casings. The smell was overwhelming.

Copper and cordite and aviation fuel. Britain took the controls. Zemer didn’t resist this time. He leaned back, closed his eyes, stayed conscious through will alone. Behind the cockpit, the crew assessed damage. Old 666 had taken 187 bullet holes, five 20 mm cannon strikes. The nose plexiglass was gone.

Wind screamed through the opening. The oxygen system was destroyed. Number two engine was shut down. Hydraulics were leaking. The radio was dead. Hit during the first attack. They couldn’t call for help. Couldn’t request emergency landing clearance. They were on their own. Port Moresby was still 500 m southwest.

2 hours of flying time at reduced speed on three engines. Abel and Kendrick worked on Zemer’s leg. They’d pulled the first aid kit from its mount, found sulfa powder and bandages. The wound was too severe for field medicine. Bone was shattered. Arteries were severed. They packed the wound with gauze, wrapped it tight, applied pressure, slowed the bleeding. That was all they could do.

Zemer needed a surgeon. Soon or he’d bleed out before they reached land. His pulse was weak, skin pale, lips blue. Shock was setting in. Johnston remained at the nose guns, scanning the sky for more fighters. The Japanese might send a second wave. Fresh aircraft from Rabul. It would take them 90 minutes to reach this area.

Old 666 would be vulnerable the entire flight back. No radio, one engine down, wounded crew, easy target. But the fighters never came. The sky remained empty, just clouds and ocean below. The bomber droned southwest alone. At 9:30 a.m., Britain spotted the New Guinea coastline land.

They’d made it across the Solomon Sea, but Port Moresby was still 200 mi inland over mountains, through weather.Old 666 was losing altitude. The three remaining engines couldn’t maintain 15,000 ft. They were down to 12,000 now, sinking slowly. The mountains ahead were 7,000 ft high. They’d cleared them barely. Zemer opened his eyes.

He didn’t remember closing them. Britain was still flying. The coastline was behind them now. Jungle below, mountains ahead. The Owen Stanley range. 7,000 ft of rock and trees between old 666 and home. Zeamer checked the altimeter. 11,500 ft. Dropping. He looked at the engine gauges. Number two was still feathered, dead. Number one was running hot.

Cylinder head temperature in the red. Oil pressure fluctuating. That engine wouldn’t last much longer. If it failed, they’d have two engines. Not enough power to clear the mountains. They’d have to ditch in the jungle. Nobody survived jungle crashes. The weather closed in at 10,000 ft. Clouds wrapped around the bomber.

Visibility dropped to zero. Britain was flying on instruments. Compass heading, air speed, altitude, rate of climb. The bomber shuddered through turbulence. Rain hammered the fuselage. Lightning flashed in the clouds. Thunder rolled. Old 666 descended through 9,000 ft. The mountains were somewhere ahead in the clouds. Britain couldn’t see them.

He flew the heading. Trusted the compass. Hoped the mountains were behind them. At 9,500 ft, they broke through the clouds. Clear air below, mountains all around. The Owen Stanley’s. Jagged peaks covered in jungle. Old 666 was in a valley. Mountains rose on both sides, higher than the bomber. Britain banked right.

Followed the valley southwest, looking for a pass through the range. The altimeter read 9,000 ft now, still dropping. Number one engine was failing. Temperature gauge pegged. The engine was cooking itself. Britain reduced power, babyed it, tried to keep it running. They needed every bit of thrust. Kindred came forward, told Britain about Zemer.

The pilot was unconscious, pulse barely detectable, breathing shallow. He’d lost too much blood. Hours had passed since the wound. The bandages were soaked through. Nothing more they could do. Zemer needed blood transfusions, surgery. They had minutes, maybe less. Britain pushed the throttles forward, risked the engines.

Speed was more important than caution now. The valley opened ahead. Port Moresby lay beyond the next ridge, 30 m. Britain climbed. Aim for the lowest saddle between peaks. 8,000 ft. Old 666 struggled upward. 700 ft per minute climb rate. Normally, it climbed at 1,000. The damaged bomber was at its limit. The ridge approached.

Old 666 cleared it by 300 ft. Trees flashed below. Then the valley opened. Port Moresby appeared ahead. 7mm air strip. Home. Britain keyed the radio. Dead. Still dead. He couldn’t call the tower. Couldn’t request emergency landing. He’d have to go straight in. Hope the runway was clear. Hope the tower saw them coming. saw the damage. Understood.

He dropped the landing gear. The hydraulics groaned. Gear came down, locked. Flaps next. They deployed partially. Hydraulic pressure was too low for full extension. The approach would be fast. Too fast. But there was no choice. Old 666 crossed the airfield boundary at 140 mph. 30 mph. Too fast.

Britain held the nose up. bled off speed. The main wheels touched, bounced, touched again, stayed down. He reversed the propellers, applied brakes. The bomber rolled down the runway, slowing the end of the runway approached. 2,000 ft left. 1,00 500. Old 666 stopped with 200 ft of runway remaining. Britain shut down the engines. The propellers windmilled.

Stopped. Silence descended. After eight hours of engine noise and gunfire and wind screaming through the shattered nose, the silence was overwhelming, almost painful. Ground crew ran toward the bomber. They’d seen it approach, seen the damage, the missing plexiglass, the feathered engine, the bullet holes covering every surface.

They knew it was bad. The crew door opened. Abel climbed out first, then Kendrick, then Pew, then Vaughn, then Dilman, then Johnston. Six men, still moving, still alive, blood soaked, exhausted, but alive. The ground crew chief climbed aboard, looked inside, saw the blood pulled on the cockpit floor, saw Zemer slumped in the pilot seat, saw the covered body beneath the catwalk in the nose.

He climbed back out quickly, told the medics waiting below, “Get the pilot last. He’s dead.” The medics carried Zeamer out on a stretcher. His face was gray, lips blue. No visible movement. Britain climbed down behind them, grabbed the lead medic’s arm, told him, “The pilot’s not dead. Check him.” The medic stopped, set the stretcher down, checked for pulse, found one, weak, threadlike, barely there, but present.

They ran for the ambulance, loaded Zeamer, drove to the field hospital at full speed, wheels throwing up dust. The doctors gave him one chance in 10, maybe less. He’d lost more than half his blood volume, both legs shattered, multiple fractures above and below the left knee, right wristtendons severed, dozens of shrapna wounds across both arms and torso.

Severe shock. His body temperature had dropped to 94°. They started transfusions immediately. Four units, then six, then 8. began surgery, worked for six hours straight, reconstructed the knee, repaired the arteries, saved his life. Johnston led the ground crew to Sarnowski’s body. They carried it out carefully, respectfully, laid it on a stretcher, covered it with a clean sheet.

The bombader had died at his guns, kept fighting with a mortal wound, shot down two zeros after the blast that should have killed him instantly after his neck was torn open. After his side was ripped apart, he’d crawled back to his position, fired until his heart stopped. Saved the mission, saved the crew, protected the nose while dying.

He was supposed to go home in 3 days. back to Pennsylvania, back to his wife Marie, back to his family of 17 siblings. Now he was going home in a casket, a hero, but dead. The ground crew chief walked around old 666 slowly counted the damage methodically. 187 bullet holes, five 20 mm cannon strikes, each one capable of destroying a fighter. Nose completely destroyed.

Oxygen system destroyed. Radio destroyed. Number two, engine destroyed. Hydraulics severely damaged. Flight controls damaged. Left wing spar cracked. Tail section peppered with holes. He looked at the surviving crew members. Asked the question, “How many fighters attacked you?” Britain said, “16, maybe 17. They came in waves.

” The crew chief shook his head. Didn’t believe it. Nobody could survive 16 fighters alone. Not possible. He climbed inside the bomber, saw the blood covering every surface, saw the thousands of spent brass casings rolling across the floor, saw the torn metal, the shattered instruments, the destroyed equipment. He believed it then.

He’d never seen anything like it. In 18 months in the Pacific Theater, he’d never seen a bomber take this much damage and survive. The photographs old 666 captured that day were developed within hours. Intelligence officers studied them carefully. The Buouah airfield photos showed 16 aircraft on the ground, confirmed the Japanese buildup.

The Bugganville coastal mapping photos were perfect. Every beach, every reef, every approach to Empress Augusta Bay, exactly what the Marines needed. On November 1st, 1943, four months after Zemer’s mission, the Third Marine Division landed at Empress Augusta Bay. They used the photos from old 666 to plan every detail, the landing zones, the approach routes, the defensive positions. The invasion succeeded.

American forces secured Bugganville. The photos captured by a dying bombardier and a bleeding pilot saved hundreds of Marine lives, maybe thousands. Zemer spent 15 months in hospitals, seven surgeries on his left leg, three on his right wrist, physical therapy for a year. He learned to walk again slowly, painfully.

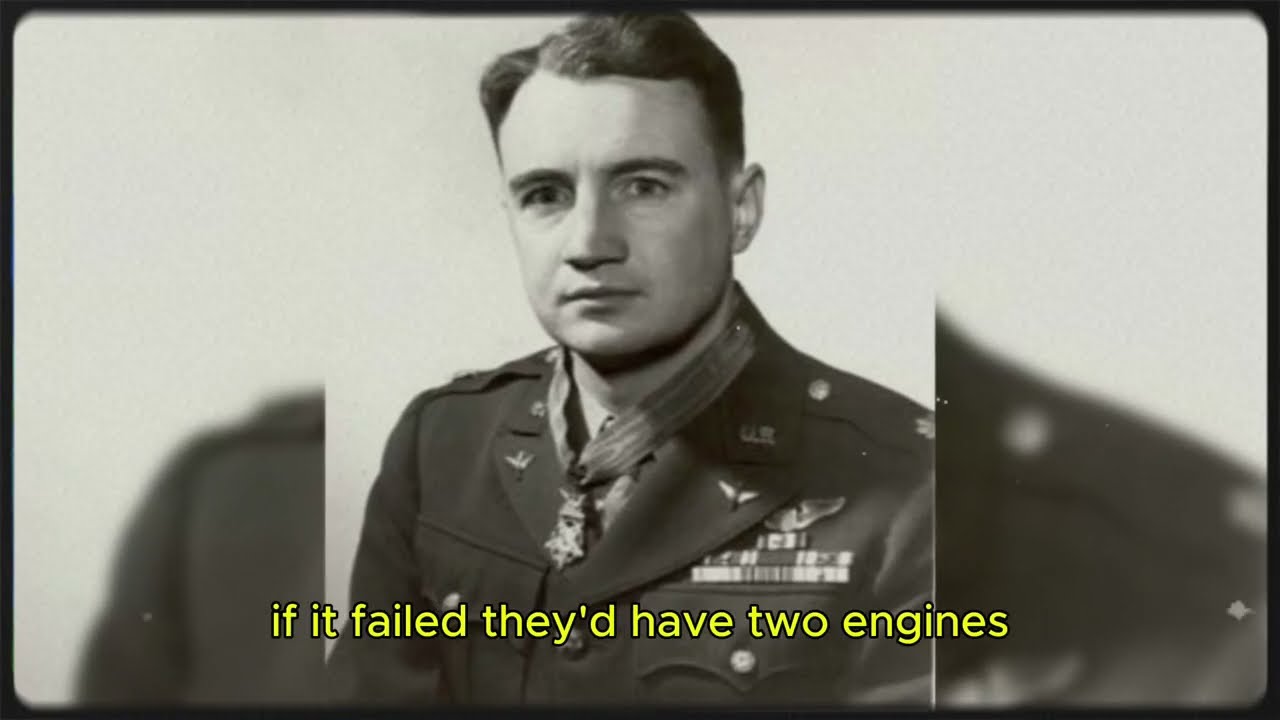

The knee never healed properly. He walked with a limp for the rest of his life, but he lived. On January 16th, 1944, seven months after the mission, General Henry Arnold presented Zeamer with the Medal of Honor in a ceremony at Walter Reed Hospital. Zemer was still in a wheelchair, still recovering. His parents stood beside him.

His mother cried. His father saluted. Two weeks earlier, on December 17th, 1943, Sarnowski had been awarded the Medal of Honor postumously. His widow, Marie, received it at a ceremony in Pennsylvania. She held the medal, looked at it, then gave it to Sarnowski’s parents. They placed it in a glass case next to his silver star next to his air medal next to the photograph of their son in his bombardier uniform, smiling, alive.

The other seven crew members received the Distinguished Service Cross, second only to the Medal of Honor. Britain, Johnston, Ael, Kendrick, Pew, Vaughn, Dilman, all seven. It remains the most highly decorated single air mission in American history. Nine men, two medals of honor, seven distinguished service crosses, five Purple Hearts.

No other crew has ever been honored like this. Not before, not since. Old 666 was repaired, returned to service, flew 18 more missions, then was retired in March 1944, flown back to the United States, used as a training aircraft, finally scrapped in August 1945. The nose plexiglass was never properly fixed. Crews who flew it later said they could still see bullet holes patched with aluminum, still see the blood stains on the floor.

The bomber had become a legend. Zemer survived the war, returned to MIT, earned a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering, worked in the aerospace industry for 30 years, married, had children, retired to Booth Bay Harbor, Maine, the place where he’d spent summers as a child, building boats, sailing. He died on March 22nd, 2007, age 88.

He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors. Section 34, grave 809. The headstone reads, “Lieutenant Colonel J. Zeamer Jr., Medal of Honor, Old 666.” That’s the story of the cursed bomberthat became the most decorated aircraft in American history. The crew that volunteered for a suicide mission. The pilot who flew 8 hours with shattered legs. the bombader who died at his guns.

If you felt something watching this story, please hit that like button. It helps us share these forgotten heroes with more people who need to hear them. Subscribe so you never miss another story like this. Drop a comment below and tell us where you’re watching from. We read every single one. Thanks for keeping these memories alive.

We’ll see you in the next

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.