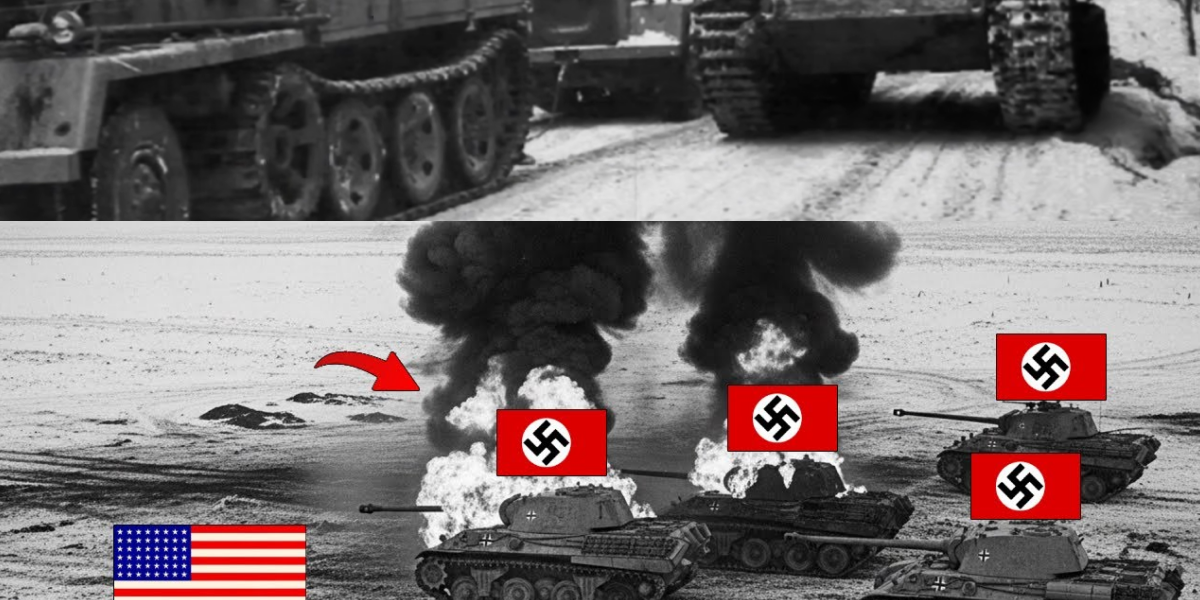

They called these tanks scrap metal, then 3 “junk” Shermans stopped a German blitz in 30 minutes. NU

They called these tanks scrap metal, then 3 “junk” Shermans stopped a German blitz in 30 minutes

The fog over the Ardennes in December 1944 was not merely a weather pattern; it was a shroud for a dying empire’s last gamble. At 01:50 on December 19, Private First Class Harry Miller sat in the loader’s seat of an M4 Sherman tank at Stoumont Station, Belgium. He was 18 years old, his hands were caked in black grease, and he was terrified.

Earlier that week, the 740th Tank Battalion had possessed exactly zero operational tanks. They were a specialized unit trained for searchlight missions, but when Hitler launched his massive counter-offensive through the Ardennes, the “Daredevils” of the 740th were told to fight as standard armor. The problem? Their promised tanks hadn’t arrived.

Desperate, the battalion was sent to the Sprimont vehicle depot. What they found was a mechanical graveyard. The depot had been evacuated so quickly that half-eaten meals sat on the tables. Scattered across the yard were battle-damaged tanks stripped for parts.

Miller and his fellow mechanics worked through a freezing night, scavengering. They found a breech block on a burned-out hull. They pulled machine guns from a shattered half-track. By 02:00, they had resurrected three Shermans and one M36 tank destroyer. They were “junk” tanks—leaking hydraulic fluid, radios crackling with static, and sights uncalibrated.

But orders had arrived: Piper has broken through. Move to Stoumont Station immediately.

THE BLIZZARD AND THE BEASTS

Joachim Peiper, the infamous SS commander, was 12 miles west. He led 58 Panzers and 5,000 fanatical troops. If he reached the Meuse River, he would split the Allied armies in half, potentially winning the war for Germany.

Standing in his way were Miller and three platoons of men in tanks that were held together by prayer and scavenged bolts.

The Amblève Valley Road was a deathtrap—barely wide enough for one tank, with 300-foot cliffs on the left and the deep Amblève River on the right. Visibility was less than 75 yards.

At 06:00, Lieutenant Charles Powers, leading the column, rounded a curve near the granite railway station. A German Panther sat waiting, camouflaged with brush, its long 75mm gun pointed directly at them.

The Panther was the superior predator. Its armor was nearly impenetrable from the front, and its gun could core a Sherman at two miles. But in the fog and the mud, the distance was barely 100 yards.

“Fire!” Powers screamed.

Corporal Jack Ashby, the gunner, pulled the trigger. The armor-piercing shell struck the Panther’s gun mantlet, deflected downward, and exploded into the driver’s compartment. The Panther erupted in a geyser of flame.

THE 30-MINUTE MIRACLE

The column pushed forward another 150 yards. Miller’s tank was fourth in line. Suddenly, a second Panther appeared, hull-down behind a stone wall.

Ashby fired again, but the shell ricocheted off the Panther’s sloped front plate. As the German gun began to traverse toward Powers’s Sherman, Powers’s loader shouted the words every tanker fears: “Gun jammed!” A spent casing was wedged in the breech.

They were sitting ducks.

That’s when Staff Sergeant Charlie Lupy’s M36 tank destroyer roared forward. Lupy had never seen an M36 before yesterday. His gunner, Corporal William Beckman, had never aimed its 90mm cannon. But the M36 was designed for one thing: killing big cats.

Beckman fired. The 90mm round punched through the Panther’s front plate like it was cardboard. A second round hit the turret ring. A third hit the ammunition storage. The Panther’s turret lifted six feet into the air before crashing back down.

Minutes later, a third Panther was spotted in a farmyard. Ashby, his gun cleared, took the shot. The shell struck the Panther’s muzzle brake dead center, causing the German gun to explode inside its own barrel—opening the steel tube up like a blooming flower.

In exactly 30 minutes, Company C had destroyed three of Germany’s finest tanks using three “junk” tanks they had assembled from a scrapyard 18 hours earlier.

THE BATTLE FOR ST. EDWARD’S

The advance had stopped, but Peiper was not finished. He still had 55 tanks in Stoumont Village.

Over the next 48 hours, the battle turned into a brutal house-to-house grind. The Americans eventually reached the St. Edward Sanatorium, a massive brick building on a hill overlooking the valley. It was a fortress.

The SS counter-attacked with fanatical fury, retaking the building and pushing the Americans back. Lieutenant Colonel Rubel, the battalion commander, realized they couldn’t win a direct assault. He spotted a self-propelled 155mm howitzer and requisitioned it on the spot. He spent the morning “sniping” at the sanatorium windows over open sights, the massive shells hitting the brick like sledgehammers.

By dawn on December 22, the Americans had retaken the building. Inside the basement, they found a miracle: 250 terrified civilians, including many children, who had been trapped there for three days.

THE COLLAPSE OF KAMPFGRUPPE PEIPER

By December 23, Peiper was surrounded on three sides. He had no fuel, no ammunition, and his elite unit was being bled dry by “junk” tanks and determined infantry.

At 22:00, Peiper gave the order: Abandon all vehicles. Escape on foot.

The “invincible” SS unit, which had murdered prisoners at Malmedy and burned villages across Belgium, slunk away into the woods. They left behind 28 heavy tanks—Panthers, Tigers, and King Tigers—and 70 half-tracks. Of Peiper’s original 5,800 men, only 800 reached German lines.

Miller entered the village of La Gleize on December 24. The town was a graveyard of smoldering Panzers. He sat on his Sherman’s turret and finally breathed.

EPILOGUE: THE DAREDEVILS’ LEGACY

For decades, the story of the 740th was buried beneath the legends of Bastogne and Patton. But in the Amblève Valley, the people never forgot.

Harry Miller survived the war, serving again in Korea and Vietnam before retiring as a Senior Master Sergeant. He rarely spoke of the grease-stained night in Sprimont or the 30 minutes that saved the Meuse.

In 1999, the Belgian town of Neufchâteau dedicated a monument to the 800 men of the 740th. Their names are engraved in stone—a quiet testament to the mechanics and tankers who proved that a war isn’t won by the “best” equipment, but by the men brave enough to make “junk” fight.

Harry Miller passed away in 2017 at the age of 89. He was one of the last “Daredevils.” He left the world with one piece of advice for the soldiers who followed him: “Stay in, do your job, and never let them tell you your tools aren’t enough.”

Because on a foggy road in 1944, three pieces of scrap metal and a handful of grease monkeys stopped the greatest armored force the world had ever seen.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.