The Wrath of Alderney: British soldiers realized the SS had turned British soil into a graveyard. NU

The Wrath of Alderney: British soldiers realized the SS had turned British soil into a graveyard

On May 16, 1945, at precisely 2:14 in the afternoon, the stone quay of Alderney Harbor felt the scrap of British steel for the first time in five years. Sergeant Thomas Whitmore stepped off the landing craft into a silence so heavy it felt like a physical weight. Behind him, forty men of the Hampshire Regiment fanned out, rifles at the high port, eyes scanning the jagged cliffs of the smallest inhabited Channel Island.

They expected a fight. Instead, they found a graveyard of secrets. The island smelled of salt, stagnant damp, and the unmistakable, charred scent of selectively burned archives. This was three miles of British soil that had been part of the Third Reich since 1940. Now, it was a crime scene.

Whitmore marched inland, past cottages with “eyes” of shattered glass and garden walls where children’s shoes lay half-buried in weeds. Then, he saw it: the barbed wire, the methodical watchtowers, and a word painted in two-foot-high concrete letters that made his blood run cold.

SYLT.

The British Army had just discovered the only SS concentration camp ever built on British territory. What they found inside would push the discipline of the British soldier to its absolute breaking point.

THE ANATOMY OF ATROCITY

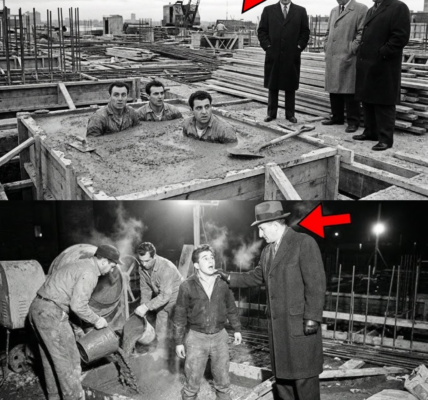

Lager Sylt was not merely a labor camp; it was a factory of exhaustion. Initially built to house foreign workers for Organization Todt, it was handed over to the SS in March 1943. When Whitmore’s unit entered the barracks, they found wooden bunks stacked three high, each barely wide enough for a skeletal frame. The walls were covered in “tally marks”—scratches made by fingernails counting days, beatings, or perhaps deaths.

Major Theodore Pantcheff, dispatched by London to document the site, would later conduct over 3,000 interviews. His report revealed a hierarchy of horror:

The SS had operated Sylt with the same industrialized cruelty seen at Belsen or Buchenwald. Prisoners were worked until they collapsed into the limestone mud. Those who couldn’t rise were executed or “selected” for termination. Pantcheff discovered a hidden tunnel connecting the Commandant’s house directly to the camp—a subterranean passage that allowed the SS to enter and exit the site of their crimes unseen by the regular Wehrmacht.

THE MOMENT OF CONTACT: ANGER VS. POLICY

The SS personnel who had run Sylt expected special treatment in defeat. They considered themselves an “Elite Guard,” separate from the regular army, answerable only to Himmler. They had operated with absolute authority over “sub-humans” on British land.

When the British Force 135 began rounding up the remaining Germans, they faced a choice. The soldiers who walked through the Sylt barracks, who saw the execution grounds and the mass graves at the base of the cliffs, were not just investigators—they were men with guns and a justified, white-hot rage.

“Sarge,” a young private named Davies whispered, standing over a pile of discarded prisoner uniforms. “This was British soil. They did this here.”

The logic of vengeance suggested summary execution. On the Eastern Front, Soviet soldiers often showed SS guards the same mercy the SS had shown their victims: none. But the British response on Alderney revealed the fundamental character of the Allied victory.

THE FOUR PILLARS OF BRITISH RESTRAINT

Institutional discipline held. When British forces located former Sylt personnel, there were no firing squads. No beatings. They were arrested, fingerprinted, and processed as Prisoners of War. This was not an act of mercy; it was a strategic and moral mandate built on four pillars:

-

Security: Cruelty breeds resistance; humane treatment breeds compliance.

-

Intelligence: Men who are treated with basic dignity are far more likely to provide actionable testimony during interrogations.

-

Reciprocity: Britain still had thousands of its own POWs in German hands. They needed to maintain the high ground to ensure the safety of their own men.

-

Moral Clarity: Britain fought for the rule of law. To become the monster while defeating the monster would invalidate the entire cause of the war.

THE DETENTION DISPARITY

By September 1945, former SS guards were held in a processing center in Hampshire. The irony was suffocating. These men, who had fed their prisoners watery soup and potato peelings, were now receiving 3,000 calories a day, as mandated by the Geneva Convention.

“We knew what they’d done,” Private William Shaw, a camp guard, later recalled. “And here we were, serving them tea and making sure their bunks were clean. It didn’t feel right. But the Sergeant said, ‘We aren’t like them. That’s the whole point.’”

THE TRIAL OF MAX LIST

The most significant interrogation involved the man who oversaw the camp, SS Hauptsturmführer Max List (a name synonymous with the camp’s leadership). During his questioning, List expressed genuine confusion at his treatment. Having seen the brutality of the war, he asked his British captors, “Why do you not simply shoot us?”

The response, documented in the official transcript, was legendary in its simplicity: “Because we are not you.”

The British built their cases methodically. They used the “Commandant’s Log Book,” a meticulous record of arrivals, “disciplinary measures,” and causes of death like “shot attempting escape” or “exhaustion.” The SS had documented their own crimes with Germanic efficiency, never realizing that the same records used to manage the camp would eventually be used to hang its officers.

In 1946, the trials began. List and his subordinates were confronted with survivor testimony and the forensic mapping of the island. The verdict was inevitable: Guilty. Many were sentenced to death or lengthy imprisonment, held accountable not through the rage of a mob, but through the cold, impartial scales of British justice.

THE SILENCE AFTER THE STORM

For decades after 1945, the story of Alderney was shrouded in a “Taboo of Memory.” The Channel Islands returned to civilian control, and the residents who had evacuated in 1940 came home to a landscape scarred by bunkers and barbed wire. There was a collective desire to move forward, leading to a silence that lasted until the 21st century.

Recent forensic archaeology, led by experts like Dr. Caroline Sturdy Colls, has finally brought the full scale of the Sylt horrors back into the light. Using ground-penetrating radar, they have identified the precise locations of mass graves and the foundations of the barracks that Thomas Whitmore first walked through in 1945.

THE FINAL RECKONING

The story of Alderney and the British response to the SS reveals a fundamental truth about strength. Real power is not the freedom to be cruel; it is the discipline to remain civil when cruelty is what you feel.

When the British Army found the SS at Sylt, they chose law over rage and civilization over barbarism. In doing so, they proved that the difference between the Allies and the Axis was not just military superiority—it was moral clarity maintained under the most extreme pressure.

Lager Sylt stands today as a ruin of stone and shadow, but the response of the men of the Hampshire Regiment stands as a monument to a different kind of victory: one where the victors refused to lose their souls in the process of winning the world.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.