The Untold Story Behind the P 51 How America Re Engineered the British Merlin

In the midst of World War II, the United States needed a solution to protect its bombers during long range missions over enemy territory. The answer was the P-51 Mustang. But its engine could not perform at high altitudes, leaving American bombers vulnerable. The solution to this problem came from an unlikely place, Detroit, Michigan.

Packard engineers took Britain’s iconic Rolls-Royce Merlin engine and in just 11 months transformed it for mass production. This was not just about copying an engine. It was about revolutionizing it. This is the story of how Packard engineers Americanized Britain’s Merlin engine, breaking every engineering rule to create a revolutionary power plant that would help secure Allied victory in the skies.

In the summer of 1940, the war in Europe was intensifying. Britain was under constant attack, and its ability to defend itself was beginning to stretch thin. The battle of Britain had been raging for almost a year, and Germany’s Luftwaffa was relentless. Britain’s finest fighters, the Spitfire and the Hurricane, had already proven themselves in combat, but their engines were in short supply.

Rolls-Royce, the company that produced the Merlin engine, was struggling to keep up with the demand. The situation was urgent. The British government knew they needed help and they looked across the Atlantic to America. At the time, American industry was booming. Factories in the United States were quickly adapting to the war effort, producing tanks, trucks, and planes in huge numbers.

But they weren’t building engines like the Merlin. The Rolls-Royce Merlin was a finely tuned piece of machinery, a handcrafted masterpiece. Each engine had about 14,000 parts, many of which were carefully fitted by hand. But mass producing this engine was a challenge no one had yet figured out. The British turned to Packard, a company known for luxury cars, not aircraft engines.

Packard wasn’t an obvious choice, but they had something that Rolls-Royce didn’t. The ability to scale production and the ingenuity to solve complex problems. Packard’s engineers were faced with a monumental task. How could they take a highly complex handbuilt engine and transform it into a mass-roduced powerhouse? The British engineers arrived in Detroit in September of 1940, bringing blueprints, complete engines, and their unwavering confidence in the design.

They needed Packard to solve a problem that seemed insurmountable, one that had the potential to change the course of the war. The engineers at Packard were excited, but also intimidated. They knew they had to act fast. As the war was escalating, the United States was still neutral, but it was clear that the conflict in Europe would soon involve them.

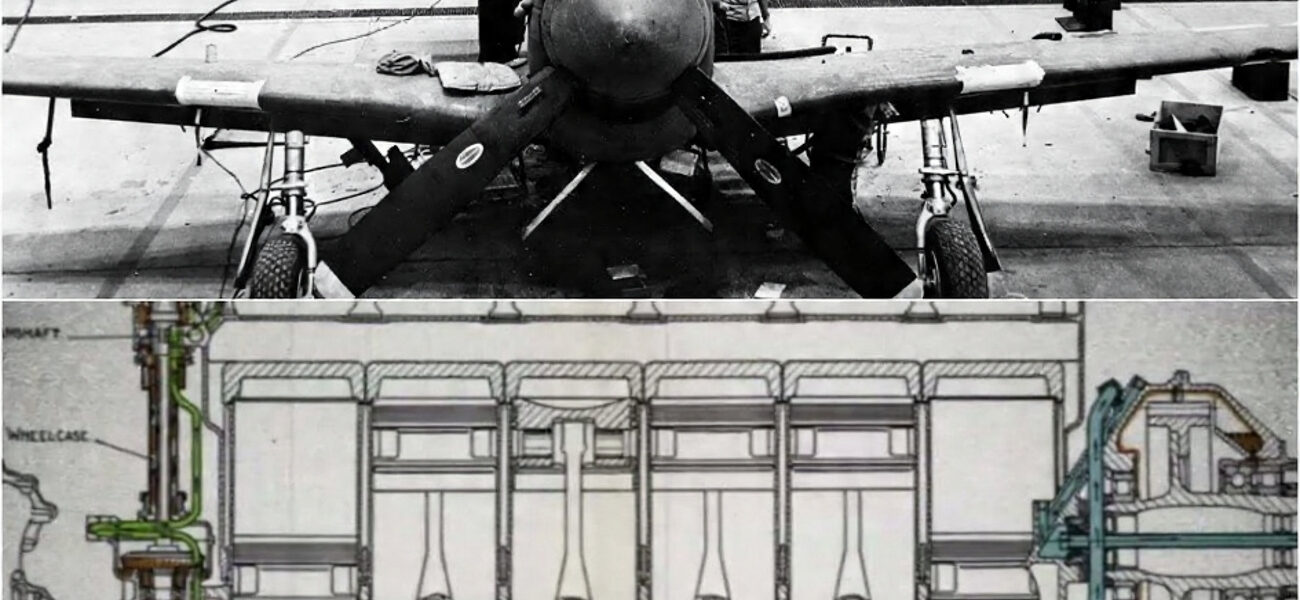

The American military needed a fighter that could escort bombers into enemy territory and provide air support. The P-51 Mustang, which had been designed by North American aviation, was already a good aircraft at low altitudes, but it struggled at higher altitudes. The solution, everyone hoped, would lie in the powerful Rolls-Royce Merlin engine.

When the engineers at Packard first saw the blueprints for the Merlin, they were taken aback by the complexity of the design. The Merlin was a finely tuned machine built for precision. But Packard’s engineers also knew that they couldn’t simply copy the British designs. The Americans had a different way of doing things.

Their manufacturing processes were focused on mass production, not the intricate hand-crafted details that defined Rolls-Royce. The question was, how could they maintain the spirit of the Merlin engine while adapting it to the needs of wartime production? The British engineers had their doubts, but the Americans were determined to try.

One of the first major obstacles was the measurement system. Rolls-Royce’s designs used imperial measurements, but these were different from the ones used in America. The tolerances and dimensions had to be converted without losing any of the engine’s performance. The challenge wasn’t just mathematical. It was about understanding the intent behind every specification.

Packard’s engineers would need to figure out how to meet the exacting standards of the Merlin while using American manufacturing methods. This wasn’t just a matter of converting inches to fractions. It was about making sure every part could fit together perfectly every time. Another challenge was the thread system used in the Merlin.

Rolls-Royce used a special thread system called the Witworth thread. This was a very precise system, but it was different from the standard American threads. The problem was clear. If Packard used American threads, the parts wouldn’t fit. They couldn’t simply switch to American threads as it would make the engines incompatible with the British aircraft.

So, Packard had to come up with a solution. They would need to create special tools and equipment to replicate the British thread system, ensuring that every bolt, nut, and screw would matchthe exact specifications of the original Merlin. This was an enormous task, but Packard’s engineers were determined to find a way.

Packard’s lead engineer, Connell Jesse G. Vincent, understood the importance of the task ahead. He knew that the success of this project would depend on how well they could adapt Rolls-Royce’s designs to American manufacturing techniques. The first step was to carefully study the Merlin engines that had been sent from Britain. They would need to understand every detail of the engine’s construction to make sure the Americanmade parts could replicate the British originals.

But this was just the beginning. As Packard’s engineers started to work through the details, they began to realize how much of the Merlin engine was designed for handfitting. In Britain, workers had carefully adjusted parts as they assembled the engine. Clearances were often loose and workers would file parts to make them fit.

This hand fitting process was impossible in a factory where parts needed to fit together perfectly on the assembly line. American mass production didn’t work with hand fitting. Every part had to be interchangeable and the tolerances had to be tighter. The challenge was clear. Could they maintain Rolls-Royce’s craftsmanship while adopting the efficiency of mass production? The answer would determine the success of the entire project.

The tension between these two philosophies, handcrafted precision versus mass production, was palpable. But the engineers at Packard were up for the challenge. They knew they had the ability to solve these problems. They were after all among the best engineers in the world and they had the resources of American manufacturing behind them.

The question now was could they replicate the genius of the Merlin without sacrificing the speed and efficiency needed for wartime production? It was a question that would take 11 months to answer and the future of the Mustang and the Allied war effort depended on the outcome. As they worked, Packard’s engineers began to develop a new understanding of how to marry precision with mass production.

They weren’t just copying a British engine. They were rethinking what was possible in manufacturing. And in doing so, they would change the future of engineering forever. By late September of 1940, Packard’s engineers had gathered all the blueprints and parts sent from Britain. The task before them was not just to copy the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine, but to transform it into something that could be produced in large quantities on an assembly line.

The engineers knew that even the smallest mistake could mean disaster. The war in Europe was intensifying and time was running out. The stakes couldn’t be higher. Packard’s engineers quickly realized that the first major hurdle they faced was the measurement system. The British system used imperial measurements, but not the same kind the Americans used.

This meant that every part had to be recalculated and converted to fit the American standards. However, the challenge wasn’t simply about converting numbers. It was about understanding the intent behind each specification. The British specifications were precise, designed for handbuilt engines, but the American manufacturing system was focused on speed and consistency.

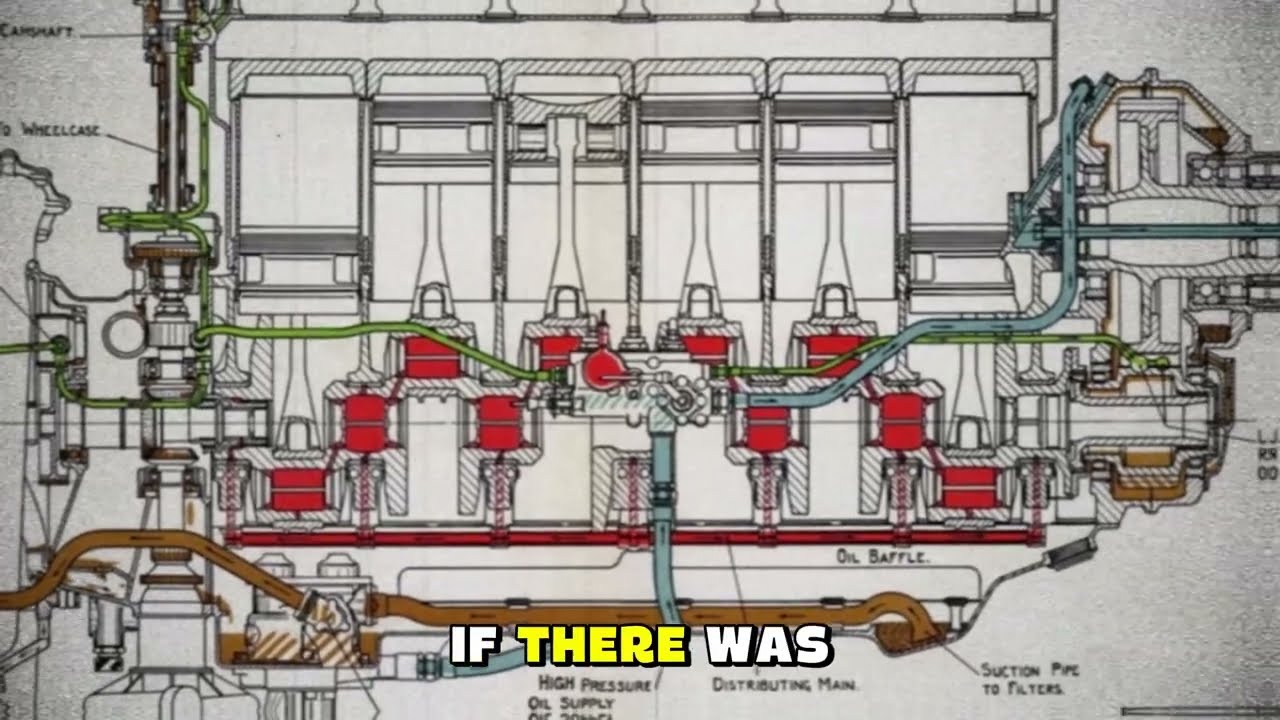

Could they maintain that precision while increasing production? One example was the crankshaft. In Britain, Rolls-Royce workers would hand fit parts to ensure a perfect fit. If there was a slight imperfection in the size of the crankshaft bearing, a worker would file it down until it fit exactly right. This method of hand fitting was impossible in the mass production process.

Packard’s engineers had to find a way to replicate the precision of the Rolls-Royce designs without relying on hand fitting. The solution was to tighten the tolerances, making sure that every crankshaft and every other part was manufactured to exact dimensions that would allow it to fit into any engine without adjustments.

This change would improve the engine’s reliability and ensure that every part would work together seamlessly on the assembly line. But the measurement issue wasn’t the only challenge. The Merlin engine used a special thread system known as the Witworth thread. The British system had a 55° angle and rounded corners, while the American system used a 60° angle with flat roots.

This meant that the bolts and nuts used in the Merlin engine were not interchangeable with Americanmade parts. Packard engineers knew that simply switching to American threads would make the engines incompatible with British aircraft. The solution was a monumental task. Packard would need to create custom tools and machinery to manufacture bolts and fasteners to the exact British specifications, but to American standards of precision.

They couldn’t simply buy these tools off the shelf. They had to be custommade. Packard went to work ordering specialized equipment from Britain and training American workers in theintricate details of the British thread system. Engineers in Detroit studied the designs closely, making sure every bolt, nut, and screw would be made exactly to specification.

This was a huge effort, but it was necessary. If they didn’t get the threads right, the entire engine would fail. Every component had to fit perfectly and there could be no compromises. The team worked tirelessly making sure that every part would be up to the task. The threads were manufactured to the tightest tolerances, ensuring that each part would fit together just as precisely as Rolls-Royce had intended.

However, the biggest challenge came when Packard’s engineers realized that Rolls-Royce’s engines weren’t designed for mass production. Rolls-Royce built each engine by hand, carefully adjusting parts as they went along. Workers would fit and refit parts until everything was just right. But Packard’s assembly line didn’t work that way.

Every part had to be interchangeable. There could be no hand fitting, no adjustments made by workers. This was a massive shift in thinking. Could Packard’s engineers maintain the precision and craftsmanship of Rolls-Royce while meeting the demands of mass production? The answer lay in a new way of thinking about the design process.

Packard didn’t just copy the Merlin engine. They reinvented it for mass production. They took each part and re-engineered it to meet the strict requirements of the assembly line while still maintaining the heart of Rolls-Royce’s design. Every part was made to fit precisely. Every measurement was recalculated to ensure that the engine could be produced efficiently and every fastener was made to the highest standards.

The result was an engine that retained all the power and reliability of the original Merlin, but could be produced quickly and in large numbers. Packard’s engineers were able to overcome these challenges because they approached the problem with an open mind. They didn’t just focus on replicating the Merlin. They focused on how to improve the manufacturing process without compromising performance.

They understood that the success of the project didn’t just depend on copying British designs. It depended on finding ways to make those designs work within the context of American mass production. The key was innovation and adaptation, not just replication. This process was far from easy.

Every day presented new challenges. Packard’s engineers had to keep the lines of communication open with the British team to ensure that they weren’t straying too far from the original design. Yet, despite the challenges, the team in Detroit was making progress. They were learning to balance precision with efficiency, craftsmanship with speed slowly but surely.

They were turning a complex handbuilt engine into something that could be mass- prodduced in the quantities needed to win the war. As the months passed, Packard’s engineers continued to refine their processes. They developed new methods for machining and casting parts that allowed them to produce the engine more quickly without sacrificing quality.

The team learned how to balance the need for precision with the demands of the assembly line. The result was an engine that could be mass- prodduced but still performed at the highest levels of reliability and power. Packard had found a way to make Rolls-Royce’s masterpiece work in the context of American industry, and they had done it without compromising a single aspect of the design.

By the end of 1941, Packard was ready to test the first Americanmade Merlin engine. The challenge had been immense, but Packard had risen to meet it. They had taken a handbuilt British engine and transformed it into something that could be produced in vast numbers. It was a victory not just for Packard but for American industry as a whole.

But the real test was yet to come. Would the engine perform as well as the British original? And could Packard meet the ever growing demand for engines as the war escalated? The answer would come soon enough. But for now, Packard had achieved something remarkable. By early 1942, Packard’s engineers had made significant progress.

They had tackled many of the major challenges that stood in their way. The engine was being re-engineered to fit the mass production model, and each part was coming together with the precision required for a fully functional assembly line. However, there were still a few critical hurdles to overcome. One of the biggest challenges was ensuring that the engine could perform at the same level as the Britishbuilt Merlin.

The Merlin engine’s performance, especially at high altitudes, was what made it so special. The two-stage two-speed supercharger system was a revolutionary design, allowing the engine to maintain its power at altitudes where most engines would lose efficiency. The problem, however, was that the supercharger was incredibly complex.

In Britain, skilled workers would balance the supercharger’scomponents by hand. Every impeller had to be carefully adjusted to ensure that it spun perfectly smoothly. The slightest imbalance would cause catastrophic failure. For Packard to manufacture these parts in large quantities, they needed to find a way to replicate this level of precision quickly and efficiently.

Packard’s engineers didn’t shy away from this challenge. They realized that they could use precision casting and machining techniques to create the supercharger components with much higher consistency than the handbalanced British version. The parts would still need to be balanced, but instead of doing it by hand, Packard developed specialized test equipment that could measure dynamic balance while the impeller was actually spinning.

This allowed them to check the balance of each impeller quickly without the need for manual adjustments. As a result, they were able to speed up production and improve the overall quality of the engine. The supercharger was no longer a bottleneck in the process. It was an engineering triumph that allowed the assembly line to run faster, more efficiently, and with greater consistency.

Another breakthrough came with the bearings. The original Merlin engine used a copper lead alloy for the bearings, which required careful break-in procedures and frequent inspection. Packard’s metallurgy team came up with a solution. They replaced the copper lead alloy with a silver lead alloy and added a layer of indium plating.

This new combination provided better load carrying capacity and reduced friction, making the bearings last longer and run cooler. Initially, the British engineers were skeptical about this change as it wasn’t part of the original design. However, when testing showed that the new bearings outperformed the originals, even Rolls-Royce quietly adopted Packard’s innovation for their own engines.

Packard’s engineers didn’t just improve the supercharger and bearings. They also made modifications to the intercooler system. Compressing air generates a tremendous amount of heat, and without an effective way to cool the air, the engine could experience detonation, which would cause it to fail. Rolls-Royce had designed an intricate cooling system with passages cast into the supercharger housing and an additional core between the supercharger outlet and the intake manifold.

Packard engineers realized that they could redesign the coolant passages to improve air flow and make the system easier to manufacture without sacrificing performance. The result was a more efficient intercooler system that helped keep the engine cool even during long periods of high performance flight. While Packard was making these technical improvements, they were also working hard to ensure that every part of the engine was interchangeable.

One of the key goals of American mass production was to eliminate hand fitting, a practice that was common in the Rolls-Royce production process. Packard engineers knew that in order to meet the demands of the war, they would need to produce engines in huge quantities. This meant that every part of the engine had to be precisely manufactured so that it could fit into any engine regardless of when or where it was made.

They couldn’t rely on skilled workers to adjust parts by hand to make them fit. Everything had to be perfect from the start. This was where Packard’s mass production experience came into play. They used a method called statistical process control, which allowed them to monitor and improve the manufacturing process continuously.

Every part was made to the same high standards, and each engine was tested rigorously before it left the factory floor. This system allowed Packard to produce engines at a rate far faster than Rolls-Royce could manage. By the time the engines were ready for production, Packard had completely transformed their factory into a precision engineering marvel.

The production line for the V1650 Merlin engine was designed for speed and efficiency with dedicated machining centers for each part of the engine. This allowed Packard to maintain strict quality control while still meeting the massive production requirements of the war effort. As Packard ramped up production in the early months of 1942, they faced another challenge.

The demand for engines was growing faster than the demand for airframes to put them in. The United States Army Air Forces needed engines for their new P-51 Mustang fighters, but the aircraft couldn’t be built fast enough to match the engine production. At its peak, Packard’s Detroit plant was producing about 400 engines per week, double the entire output of Rolls-Royce in Britain.

The demand for the P-51 Mustang was so high that the engine production was outpacing the aircraft assembly lines. Yet, despite this overwhelming demand, Packard was able to meet the challenge. They kept pushing forward, working tirelessly to build the engines that would help the Allies win the war. By mid 1943, Packard had achieved a level ofproduction that was nothing short of extraordinary.

The V1,650 engine based on the advanced Merlin 63 was powering the P-51B Mustang, the version of the aircraft that would become the war-winning escort fighter. With a two-stage supercharger that could maintain over 1,200 horsepower at altitudes of 40,000 feet, the Mustang could escort American bombers deep into enemy territory, providing muchneeded protection against the Luftwaffa.

The P-51 Mustang was no longer just a good fighter at low altitudes. It was a formidable force at any altitude and it played a key role in the Allied victory. Packard’s innovation didn’t just change the outcome of the war. It changed the way engines were made forever. The methods they developed for mass production, including precision casting, statistical process control, and dedicated tooling, became fundamental to modern aerospace manufacturing.

The Packard Merlin engine was a testament to American ingenuity, a symbol of how innovation and determination could overcome seemingly impossible challenges. As Packard’s engineers pushed forward in their work, they faced one of the most difficult challenges of all, the threads. The Rolls-Royce Merlin engine used a unique thread system known as the Witworth thread, which was different from the thread systems used in American manufacturing.

The British thread system had a 55° angle and rounded roots, while American threads used a 60° angle with flat roots. This meant that the bolts and fasteners in the Merlin engine couldn’t be directly replaced with Americanmade parts. If Packard tried to use American threads, the components wouldn’t fit and the engines would be rendered useless.

For the engineers at Packard, this was a major problem. The solution wasn’t simply to switch to American threads. It would make the engines incompatible with British aircraft and spare parts. They had to find a way to replicate the British thread system to the highest standards of American manufacturing. This was a complicated task because the American workers had never worked with the British Witworth thread system before.

It was a thread style most of them had never seen and it was unlike anything they had ever worked with. The scale of this task became clear to everyone at Packard. The factory would need to manufacture every single bolt, nut, and fastener with the exact British specifications. They couldn’t take shortcuts.

Every part had to be made to match the Merlin’s design precisely. This wasn’t just a matter of making a few custom parts here and there. It was about creating thousands of pieces with a level of precision that was almost unheard of at the time. The engineering team had to develop new tools and equipment to create the British style threads with the level of accuracy that American mass production required.

Packard’s engineers didn’t hesitate. They immediately began working on designing custom tooling to make the required threads. They ordered special equipment from Britain, including thread measuring devices and dyes, and trained American workers on how to make the new parts. Many of the workers in Detroit had never even heard of the British thread system, let alone worked with it.

But Packard’s engineers were determined to succeed. And they worked closely with the workers, making sure everyone understood the importance of the task at hand. It wasn’t just about the tools. It was also about precision. Packard’s engineers knew that the threads had to be made with incredible accuracy.

If a thread was even slightly off, the parts wouldn’t fit and the entire engine could fail. So, they used the latest in precision measurement techniques to ensure that every bolt, nut, and fastener was within the exact specifications. Every thread had to match the British design down to the smallest detail, and every fastener had to be made to the highest standards of quality.

It was a huge effort, but Packard’s engineers were up for the challenge. One of the most critical aspects of the thread issue was that the American workers had to produce the threads with a level of precision that was typically only seen in highly skilled, handfitted assembly. This was not something that was done on a typical assembly line.

The workers at Packard had to use specialized machines to produce threads that were so accurate it was difficult for even the engineers to believe. But they did it. Each piece was made to exact specifications, and the threads were so precise that they could easily interchange with the Britishmade parts.

The process wasn’t quick, but it was effective. As Packard began to produce parts with the new threads, they tested them rigorously to make sure they fit perfectly. The engineers worked closely with the machinists and workers on the floor to ensure that every part was made correctly. The testing was critical because Packard needed to guarantee that each part would fit together with precision just as Rolls-Royce’s enginesdid.

The engineers made sure that every part was checked and rechecked to ensure it met the exact standards required. As the weeks went by, Packard’s engineers continued to refine the process and the quality of the threads improved. The new tooling worked well, and soon Packard had a steady supply of parts with the British standard threads.

The workers had learned the intricacies of the British thread system, and they could produce the parts with remarkable consistency. What had once seemed like an insurmountable problem was now becoming a part of Packard’s daily routine. The success of the Thread project was a turning point for the entire production effort.

The engineers at Packard had solved one of the most complicated problems they faced in replicating the Merlin engine, and they had done it in record time. The British engineers who had been skeptical of the American manufacturing process were beginning to see that Packard wasn’t just replicating the Merlin engine, they were improving it.

The British threads were now being made to tighter tolerances than Rolls-Royce had ever achieved, and the engines could be produced more efficiently. But the thread crisis wasn’t the only challenge that Packard faced. They still had to deal with the overall complexity of the Merlin engine, the supercharger system, the bearings, the cooling system.

Every component had to be re-engineered for mass production, and each change needed to be carefully tested to make sure it didn’t compromise the engine’s performance. But with every problem that arose, Packard’s engineers rose to meet it. The thread issue had been one of their biggest challenges, but they had solved it by embracing innovation and precision manufacturing.

By early 1943, Packard had proven that they could take a hand-crafted British engine and turn it into a mass-roduced American powerhouse. The P-51 Mustang powered by the V1,650 Merlin was now a fighter that could fly at high altitudes where the Luftwaffa had once ruled. With the engines now rolling off the production lines in Detroit, Packard’s transformation of the Merlin engine was complete.

The P-51 Mustang would go on to become one of the most iconic aircraft of World War II, and Packard’s engineering triumph would remain one of the most impressive feats of industrial innovation in history. By early 1943, Packard’s engineers had made enormous strides in refining the Merlin engine for mass production.

They had overcome the challenges of thread compatibility, measurement systems, and the need for precise tolerances. However, one major hurdle still loomed large, the supercharger. This part of the Merlin engine was critical to its high altitude performance. Without it, the engine wouldn’t be able to deliver the same power at altitudes where the air was thin, and the P-51 Mustang would be a much less effective fighter.

The supercharger was the heart of the engine’s ability to maintain its performance at high altitudes. Rolls-Royce had handbalanced each supercharger impeller to ensure it operated smoothly at speeds exceeding 30,000 RPM. But could Packard replicate this process for mass production? The supercharger in the Merlin engine used a two-stage two-speed system.

It employed two impellers on the same shaft. Driven through a set of gear trains. In low-speed mode, the gear ratio was six 391 to1. While in high-speed mode, activated by a hydraulic clutch, the ratio jumped to 8.095:1. These impellers had to be balanced with extraordinary precision to avoid engine failure.

A single small imbalance in the impeller would cause vibration and lead to damage. In Rolls-Royce’s production system, skilled workers balanced the impellers by hand, carefully removing or adding tiny amounts of material until the impellers were perfectly balanced. This hand balancing process, though effective, was slow and labor intensive.

Packard, however, had a different approach in mind precision and consistency. Packard’s engineers quickly realized that the solution lay in precision casting and machining. Instead of relying on the traditional hand balancing technique, they developed new methods of manufacturing the supercharger impellers with much higher accuracy.

They used advanced casting techniques and highly specialized machinery to create impellers that were nearly perfect from the start. These impellers required much less manual balancing, which greatly sped up the production process and ensured that every impeller was made with the same high level of consistency. With each impeller being more accurately cast, the time-consuming process of hand balancing was reduced and the risk of human error was minimized.

Packard also developed special test equipment that allowed them to measure the dynamic balance of the impellers while they were actually spinning. This equipment could detect even the slightest imbalance during testing and the engineers could make any final adjustments necessary before theimpellers were installed in the engines.

This method ensured that the impellers would operate smoothly and efficiently without requiring hours of manual labor. As Packard made improvements to the supercharger, they also focused on improving the intercooler system. Compressing air generates tremendous heat, and without a way to dissipate that heat, the engine could overheat and fail.

The Merlin’s intercooler system had been designed by Rolls-Royce to handle the intense heat generated by the supercharger, but Packard saw an opportunity to improve it. They redesigned the cooling system to increase its efficiency without sacrificing performance. They adjusted the coolant passages for better air flow.

ensuring that the engine could operate at high power levels for extended periods without overheating. The new system was easier to manufacture and more effective at keeping the engine cool, even during long missions over enemy territory. The redesign of the supercharger and intercooler system was a turning point in Packard’s mass production efforts.

These components were critical to the Merlin engine’s ability to maintain high performance at altitude, and Packard had found a way to improve them while making them easier to produce. The changes they made to the supercharger system allowed the engines to be produced faster with fewer chances for error.

But it wasn’t just the supercharger that was being improved. Packard was rethinking every aspect of the engine to make it easier to manufacture without sacrificing the quality that made the Merlin engine so special. As the production ramped up in 1943, Packard was producing engines faster than North American aviation could build the airframes for the P-51 Mustang.

The production lines at the East Grand Boulevard plant were running at full capacity and the engines were rolling off the assembly line with unprecedented speed. At the peak of production, Packard was completing about 400 engines per week, double the output of Rolls-Royce’s factories in Britain. This was a staggering achievement, and it was made possible by Packard’s dedication to improving the manufacturing process at every step.

They had taken a British masterpiece carefully handcrafted by skilled workers and turned it into a machine that could be mass- prodduced in the quantities needed to win the war. The P51 Mustang, now powered by the Packard built Merlin engine, was a gamecher. It was a fighter that could sustain operations at altitudes where the Luftwaffa had previously ruled.

The new Merlin engines gave the Mustang the power to escort Allied bombers deep into enemy territory, providing muchneeded protection against the Luftwaffers fighters. The Mustang was no longer just a fast and agile fighter at low altitudes. It was now a formidable presence at any altitude, capable of taking on enemy aircraft in a wide range of conditions.

The success of the P-51 Mustang was a direct result of Packard’s engineering innovations. The improvements made to the supercharger and intercooler system were critical to the Mustang’s performance, and they had been made possible by Packard’s approach to mass production. The American engineers had taken the original design of the Merlin engine and transformed it into something that could be produced in large numbers without compromising the performance that made the engine so legendary.

By the end of 1943, Packard’s achievements in engine production had become a key factor in the success of the Allied Air campaign. The P-51 Mustang powered by the Packard-built Merlin engine played a crucial role in escorting bombers on long range missions over Europe. It became one of the most effective fighter aircraft of World War II, helping to turn the tide in the air war over Europe.

The success of the Merlin engine and the P-51 Mustang proved that American innovation combined with British design could produce something truly extraordinary. Packard’s ability to mass-roduce these engines while maintaining the integrity of the original design was a triumph of engineering and manufacturing. It wasn’t just about building engines.

It was about rethinking what was possible in manufacturing and creating systems that allowed for efficiency without sacrificing quality. This success would leave a lasting legacy on the future of aerospace manufacturing, and it would continue to influence engineering techniques long after the war ended. By the end of 1943, Packard’s transformation of the Merlin engine was complete.

The P-51 Mustang, now powered by the Packard built Merlin V1,650, was ready to prove its worth in the skies. This was the moment that Packard engineers had been working toward for more than a year. The aircraft, which had once struggled to operate at high altitudes with the Allison engine, was now a powerhouse. It could fly higher, faster, and longer than ever before, and it would change the course of the war.

The Mustang’s new ability to operate at altitudes where the Luftwaffa once hadthe advantage gave the Allies a powerful new weapon in their arsenal. The improved Merlin engine, now mass-produced by Packard, provided the Mustang with more than just speed. It provided endurance, reliability, and the power to defend American bombers deep into enemy territory.

No longer were Allied bombers vulnerable to the relentless attacks of German fighters above 30,000 ft. With the P51 Mustang escorting them, the bombers could fly deeper into enemy airspace, and they could do so with confidence, knowing that their escorts had the altitude advantage. The P-51 Mustang quickly became one of the most iconic aircraft of World War II.

It was fast, agile, and deadly at high altitudes, and it proved to be a gamecher for the Allies. The Mustang’s ability to escort bombers all the way to their targets and back dramatically reduced the losses suffered by American bomber crews. Before the Mustang, the B17 Flying Fortress and other bombers were sitting ducks for German fighters once they crossed into enemy airspace.

Now with the Mustang providing cover, the bombers were much less vulnerable. The new engine developed by Packard was at the heart of this success. But Packard’s success wasn’t just about building a better engine for the P51. It was about proving that American industry could take on a problem and solve it in a way that no one else could.

The methods Packard developed to produce the Merlin engine revolutionized how aircraft engines were made. The use of precision casting, statistical process control, and dedicated tooling for consistent quality would become standard practices in aerospace manufacturing for decades to come. Packard had taken a British design and turned it into something that could be mass- prodduced quickly, efficiently, and to the highest standards.

By the time the war ended in 1945, Packard had built more than 55,000 Merlin engines, more than all of Rolls-Royce’s production in Britain combined. The success of the Merlin engine and the role it played in the P-51 Mustang’s victory in the skies is a testament to the power of innovation, collaboration, and mass production.

The engine was responsible for one of the most iconic aircraft of World War II, and it played a major role in the Allied victory in Europe. But Packard’s legacy didn’t end with the war. The innovations they made in precision manufacturing would have a lasting impact on the future of aerospace engineering. The principles they pioneered, making parts interchangeable using statistical process control and developing precision tooling, became standard practices in the aerospace industry after the war.

The techniques Packard developed in the factories of Detroit, influenced the design and production of jet engines for decades, and they continue to shape how aircraft are built today. In the years following the war, many of the original Packard Merlin engines were still in use, powering both military and civilian aircraft.

The Canadian War Plane Heritage Museum in Hamilton, Ontario, still operates a Lancaster bomber with Packard Merlin engines, a living tribute to the legacy of American innovation. At air shows, the distinctive howl of the Merlin engine still fills the skies. A reminder of the engineering triumph that helped win World War II.

The story of the Packard Merlin is not just a tale of one engine. It’s a story about how American ingenuity when combined with British innovation created something truly extraordinary. The British designed the Merlin to be a masterpiece of aviation technology and the Americans turned it into something that could be mass- prodduced to meet the demands of total war.

It was a partnership that changed the course of history. The sound of the Packard Merlin engine still echoes in the skies today, reminding us of the engineering brilliance that powered the P-51 Mustang to victory. And it’s a reminder that sometimes the greatest victories don’t come from the battlefield. They come from the factories where engineers, workers, and innovators come together to solve the impossible.

The story of the Packard Merlin is a legacy of determination, precision, and collaboration that helped shape the world we live in

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.