The Junk Tank: How a Major built a secret weapon from scrap metal to save 70,000 Marines from certain death. NU

The Junk Tank: How a Major built a secret weapon from scrap metal to save 70,000 Marines from certain death

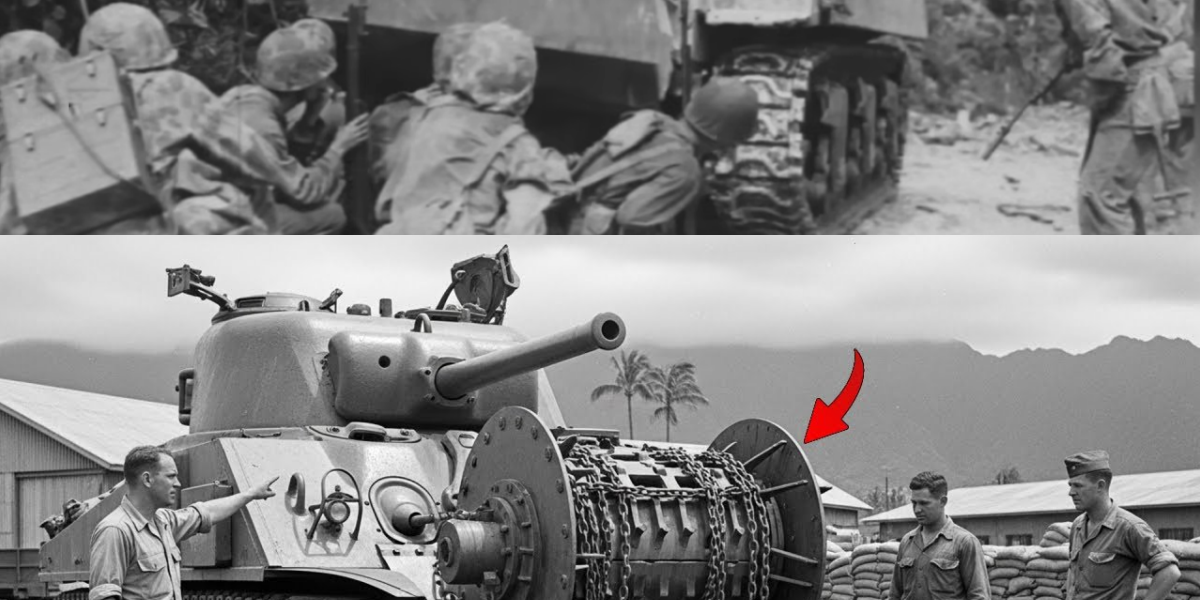

The air inside the steel hull of the M4 Sherman was a suffocating 110 degrees, smelling of grease, sweat, and impending death. At 9:42 a.m. on June 19, 1944, Major Robert Morton Neiman, commander of C Company, 4th Tank Battalion, watched through his periscope as Saipan became a slaughterhouse.

Neiman was a man of action, a thirty-two-year-old veteran who had already earned a Navy Cross. But as he watched a direct hit from a Japanese 75mm anti-tank gun turn his lead tank into a funeral pyre of black smoke, he realized that courage wasn’t enough. The Japanese had turned the volcanic ridges of Saipan into a fortress, but their deadliest weapon wasn’t the artillery—it was the invisible garden of mines buried in the ash.

By nightfall, Neiman’s company had lost six Shermans. Within a week, nearly one-third of the division’s armor was gone, most of it immobilized by landmines that blew the heavy 70-pound links of tank tracks into scrap metal.

The Maui Think Tank

After the brutal victory on Saipan, the 4th Marine Division retreated to Maui to lick its wounds and prepare for a rock the world would soon know as Iwo Jima. Neiman knew the mines there would be worse. Japanese intelligence indicated they were using 500-pound aircraft bombs buried nose-up, triggered by simple pressure switches.

Neiman had read about British “mine flail” tanks used in North Africa—vehicles with rotating drums and heavy chains that beat the ground to detonate mines safely. But the Pacific Theater was the “poor cousin” of the war; all the high-tech gear was in Europe for D-Day. If Neiman wanted a flail tank, he’d have to build it himself out of trash.

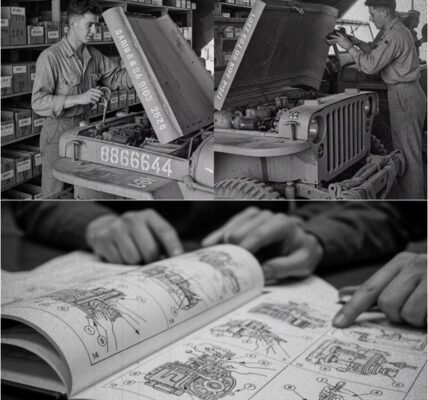

In November 1944, Neiman walked to the “vehicle graveyard” at the battalion motor pool. There, sitting among rusted chassis and stripped engines, was a beat-up M4A2 dozer tank named Joker. It was headed for the scrap heap.

“Can you make it spin?” Neiman asked Gunnery Sergeant Sam Johnston, the battalion’s best mechanic.

Johnston, a veteran who had kept tanks running on Guadalcanal with spit and baling wire, spat a stream of tobacco juice. “Give me Staff Sergeant Ray Shaw and free rein of the junkyard, and I’ll make it sing.”

Engineering from the Grave

The team spent three days scavaging. They found their centerpiece in the remains of a destroyed 2.5-ton truck: a rear axle and differential. It was six feet of solid steel.

The challenge was power. A tank engine is designed to turn the tracks, not external hardware. Johnston did something that would have gotten him court-martialed in a peacetime army: he cut a four-inch hole directly through the Sherman’s thick frontal armor.

He salvaged a transmission from a wrecked Jeep and bolted it to the floor of the Sherman’s hull. He ran a drive shaft from the tank’s drivetrain, through the Jeep transmission, out the hole in the armor, and into the truck differential.

The “Stinger,” as they began to call it, featured a rotating drum mounted on a heavy steel frame. From the drum hung forty-two heavy steel chains. When engaged by the bow gunner, the truck axle would spin at high speed, whipping the chains against the ground with enough force to pulverize rock—and detonate high explosives.

The Test of Fire

In mid-December, the division commanders authorized a live-fire test. They buried twenty captured Japanese Type 93 mines in a forty-yard stretch of Maui scrubland.

Neiman stood fifty yards back, his heart hammering. The Joker roared to life. Johnston engaged the flail. The chains became a blur of steel, creating a roar that drowned out the engine. As the tank crawled forward at two miles per hour, the first mine detonated.

A massive column of dirt and black smoke shot fifty feet into the air. Debris rained down on the turret. The tank disappeared in the cloud.

“Is he out?” someone yelled.

The Joker emerged from the smoke, chains still screaming, still beating the earth. It triggered nineteen more mines in succession. When the tank reached the other side, the Marines cheered. They had built a life-saver out of truck parts and a Jeep transmission.

However, a piece of shrapnel had punctured the thin steel casing of the differential. Neiman realized their “shield” was still vulnerable. That afternoon, without waiting for orders, the mechanics welded thick, quarter-inch steel plates around the mechanism, creating an armored box that could shrug off anything short of a direct artillery hit.

The Black Sands of Iwo Jima

February 19, 1945. D-Day.

The 4th Tank Battalion landed on the eastern beaches of Iwo Jima at 9:30 a.m. The reality was worse than any nightmare. The volcanic ash wasn’t sand; it was soft, black powder, eighteen inches deep. Tanks sank to their bellies immediately.

Neiman’s flail tank, commanded by Sergeant Rick Haddex, struggled for purchase. The extra weight of the flail on the bow made the tank nose-heavy, causing it to dig into the flour-like ash.

By 2:00 p.m., they had advanced 400 yards. Haddex spotted a line of small red flags—classic Japanese markers for a minefield. He radioed for permission to engage the flail. The drum began to spin, the chains whistling in the salt air.

What Haddex didn’t know was that these weren’t mine markers. They were range markers for Japanese heavy mortar teams hidden on the heights of Mount Suribachi.

The Japanese had been waiting for a high-priority target to move into the “kill box.” The first mortar round landed twenty yards short. The second cracked the driver’s periscope. The Joker tried to maneuver, but the weight of the flail and the softness of the ash acted like an anchor. They were stuck, sitting ducks under a deluge of steel.

The Cost of Progress

A second Sherman moved up under heavy fire, hooked a tow cable to the Joker, and spent twenty harrowing minutes dragging the flail tank backward out of the impact zone. They survived, but the mission proved a bitter truth: the terrain of Iwo Jima was an enemy even scrap-metal genius couldn’t defeat. The ash was too deep for the flail to reach the mines without the tank getting bogged down.

Ultimately, the clearing fell back to the combat engineers—men with metal detectors and bayonets who crawled on their bellies through the ash. They cleared the paths, but the casualty rate was staggering.

The Legacy of the Joker

The 4th Tank Battalion lost thirty-three Shermans on Iwo Jima. Major Neiman survived the war, leaving the Marine Corps in 1946 to become a successful lumber retailer. He died in 2003, a quiet hero of a forgotten innovation.

Neiman’s flail tank didn’t clear the path to the airfields of Iwo Jima, but it proved the “Marine way”: that when the world gives you junk, you build a shield. His design became the blueprint for post-war mine-clearing vehicles.

Today, modern armies use sophisticated robotic flails to save lives in places like Ukraine and the Middle East. They are gleaming, high-tech machines, but they all trace their lineage back to a group of muddy Marines on Maui, a wrecked truck, and a pickle-jar-sized hole in the front of a tank.

Major Neiman taught the world that a leader’s job isn’t just to give orders—it’s to find a way when the manual says there isn’t one.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.