The ISOLATED Danger of LRRP Teams in the Vietnam War

October 21st, 1968. The AA Valley, Thuathien Province. The sound of the war is not the explosion. The sound of the war is the wind. It is the specific tearing wind generated by the rotor blades of a UH1D Huey helicopter banking hard at treetop level, pulling two G’s in a flare that feels like it might snap the airframe in half.

For the six men sitting on the floor of the cabin, legs dangling out into the slipstream, this wind is the last connection to the world of steel, hot chow, and relative safety. Below them is a blurred tapestry of triple canopy jungle, a rolling ocean of chaotic green that hides everything and reveals nothing.

The door gunner, a kid who looks 19 but has the eyes of a 50-year-old, leans out and hammers the treeine with his M60, not because he sees a target, but to keep the heads down of anyone who might be watching. It is a suppressive insertion, a violent auditory mask for the six ghosts about to drop into the machine. The pilot’s voice crackles over the headset, tiny and distant. Go, go, go.

There is no hesitation. There is no looking back. You do not step out of the helicopter. You fall out of it, trusting that the skid is low enough that you won’t break a leg and high enough that the jungle floor won’t impale you. Six bodies hit the elephant grass in a practiced rolling collapse. They do not run. They freeze and then the helicopter leaves.

This is the most dangerous moment in the life of a longrange reconnaissance patrol soldier. The sensory shift is violent enough to induce vertigo. One second. You are inside a vibrating aluminum box filled with the deafening roar of a lycoming T-53 turbo shaft engine, the smell of burnt JP4 fuel, and the comforting presence of heavy machine guns.

The next second, the chopper tilts its nose down and screams away, taking the noise, the wind, and the link to civilization with it. The silence that follows is not peaceful. It is heavy. It is a physical weight that presses against the eardrums. It is the silence of a cathedral before the first note of a funeral durge. For the first five minutes on the ground, the six men, team 22, do not move a muscle.

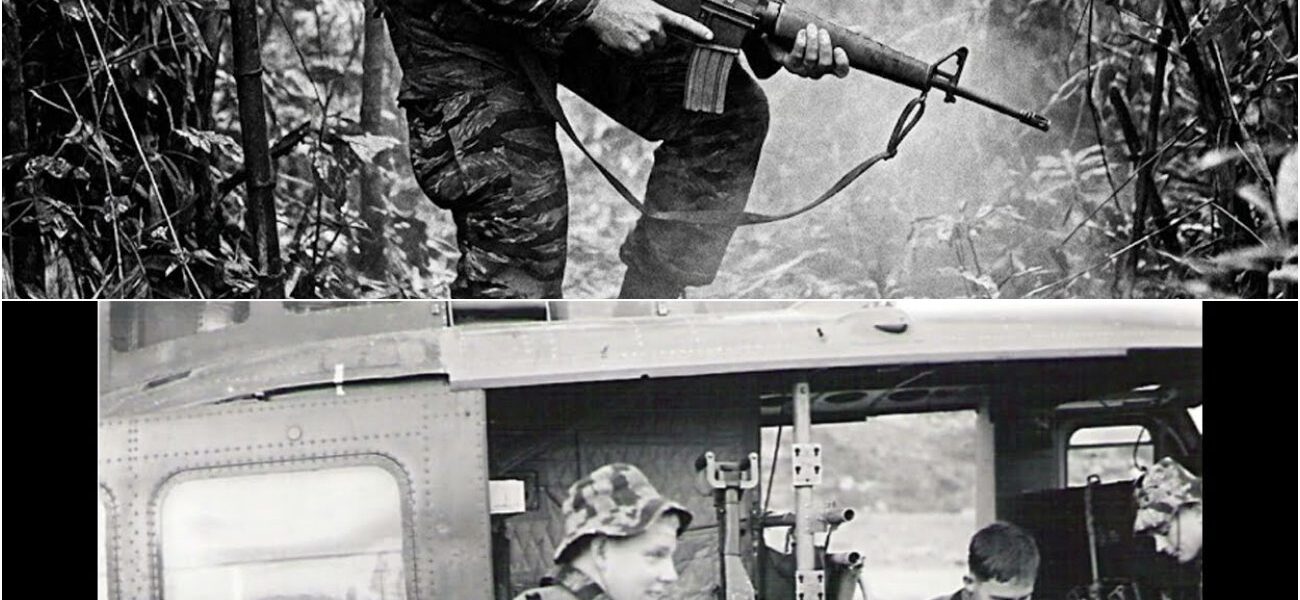

They do not adjust their rucks sacks. They do not chamber around. They do not swat the mosquitoes that immediately begin to swarm their faces. They lay flat in the tall grass, their camouflaged tiger striped fatings blending into the shadows, their eyes scanning the perimeter, their ears straining against the sudden quiet.

They are listening for the reaction. If the North Vietnamese army is here, if they watched the bird come in, the mortar rounds are already in the tube. The RPD machine guns are being swiveled. The silence will be broken by the thump, thump thump of outgoing fire. Every second that ticks by without that sound is a victory. 10 seconds, 30 seconds, a minute.

The jungle begins to reset. A bird calls out. A harsh metallic screech. A monkey chatters in the distance. The wind rustles the bamboo. These are the sounds of life, which means there are likely no humans nearby moving toward them. Humans are noisy predators. They silence the nature around them.

This is the reality of the LRP. You are six men in a box of operations that measures 10 square kilmters and you are the only friendly souls in that entire grid square. You are 10 miles outside the range of friendly artillery. You are 40 minutes of flight time from the nearest quick reaction force. You are 160 lb of meat and equipment dropped into an ecosystem designed to kill you.

Hunting an enemy who knows this terrain better than you know your own backyard. The United States military in Vietnam is a machine of massive industrial scale. It moves millions of tons of supplies, deploys thousands of aircraft, and rains down firepower that can alter the geography of a mountain. But that machine is blind.

It is a nearsighted giant flailing in the dark. It can crush anything it catches, but it cannot catch what it cannot see. And in 1968, the enemy is invisible. The Vietkong and the North Vietnamese army do not fight in the open unless they choose to. They move under the canopy along the Ho Chi Min Trail, a logistics network of blood and bicycles that defies aerial interdiction.

To find them, the giant needs eyes. It needs optic nerves that extend deep into the nervous system of the enemy. It needs the LRPS. But to understand the isolated danger of these teams, you have to understand the math of their existence. This is not a platoon sweeping a village. This is not a company-sized air assault. This is an actuarial gamble.

The army bets six lives to save 600. If a LRP team spots a regiment moving south, they can call in air strikes that decimate the enemy before a major battle ever begins. The return on investment is astronomical. But the risk profile for the assets, the men on the ground, is off the charts. They are operating in what is known as Indian country, a term borrowed from the American frontier, loaded with theimplication of hostile territory where the map is blank and the rules of civilization do not apply.

Here the doctrine of fire and maneuver is useless. You cannot maneuver against a battalion when you have six rifles. You cannot gain fire superiority when you are outnumbered 200 to one. Your only armor is invisibility. Your only shield is silence. The men who volunteer for this duty are a specific breed. They are not the loud barb brawling stereotypes of war movies.

Those men die quickly in the LRPS. The loud ones lack the patience to sit perfectly still for 14 hours while ants crawl into their ears. They lack the discipline to urinate in a plastic bag inside their pants because the sound of a zipper or the smell of ammonia on a tree trunk could give away their position. The successful LRP is often an introvert. He is a hunter.

He is observant, meticulous, and possessed of a terrifyingly high threshold for psychological pressure. He is the kind of man who checks his gear four times before the mission, not out of fear, but out of a professional understanding that a rattling canteen cover is a death sentence.

Let’s zoom out from the Asia Valley for a moment and look at the systemic architecture that places these men here. By 1967, General William West Morland’s strategy of search and destroy is hitting a wall of diminishing returns. The enemy is elusive. They engage only when the odds are in their favor. Usually, when they can hug American units so close that air power and artillery are negated.

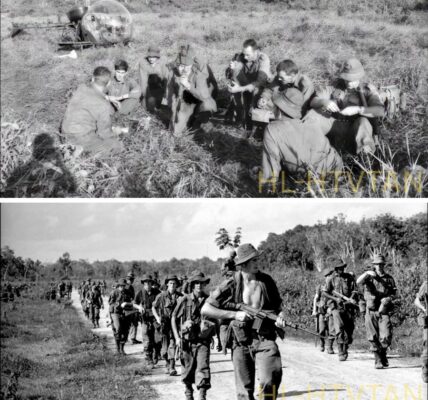

To counter this, the US Army needs to find the enemy before the ambush is sprung. They need deep penetration. This necessity births the provisional longrange patrol companies which eventually evolve into the 75th Ranger Regiment. But in the mid to late60s, these units are often ad hoc collections of volunteers attached to divisions like the 101st Airborne, the first cavalry or the fourth infantry.

They are the bastard children of the division, often lacking standard equipment, scavenging for better gear, and operating on a leash that is frighteningly long. The standard infantryman, the grunt, lives a life of misery. Certainly, he carries heavy loads, walks through swamps, and fights bloody battles.

But the grunt is almost always part of a herd. He has a squad, a platoon, a company. If he gets into trouble, there are 80 other rifles around him. There is a mortar platoon at the firebase behind him. There is a sense of collective mass. The LRP has none of that. When the helicopter flares and leaves, the isolation is absolute.

It is a psychological state as much as a physical one. You are acutely aware that every single person within a 20 m radius wants to kill you and there are thousands of them. Let’s look at the gear. Because in the LRP world, equipment is not just tools. It is a life support system. The average load for a LRP soldier on a 5-day mission is between 80 and 100 lb.

This is not the standard issue kit. This is a curated Museum of Survival. First, the weapon. The M16A1 is standard, but it is modified. The sling swivels. Those metal loops that hold the carrying strap are taped down with black electrical tape or green 100 mph tape. Why? Because metal clicking against metal sounds like a gunshot in the jungle silence.

The flash suppressor might be removed or replaced. Some point men carry a saw-off M79 grenade launcher, a Thumper cut down to pistol size, loaded with a buckshot round for close contact ambushes. It is a desperate weapon for a desperate moment. The moment you bump into an NVA soldier on a trail and have.5 seconds to erase him. Then the rucks sack.

The standard lightweight rucks sack is stripped of its metal frame if possible or heavily padded to reduce profile and noise. Inside the hierarchy of needs is ruthless. Water is the king. In the humid oven of the jungle, dehydration kills faster than the Vietkong. A LRP carries 10 to 14 quarts of water. That is 20 to 28 lb of water alone.

They use collapsible cantens, soft plastic bladders that don’t slosh like the rigid issue cantens. A sloshing canteen is a beacon. Food is a distant second to water and ammunition. Standard crations are too heavy and too bulky with their metal cans. LRPS use the specialized long range patrol ration, a freeze-dried meal in a pouch that is the grandfather of the modern MRE.

It weighs a fraction of a seat. You add water to it if you have water to spare and eat it cold. You never ever light a fire. The smell of heating tabs or wood smoke travels for miles. You eat cold spaghetti with meat sauce reconstituted with iodine treated water that tastes like a swimming pool while sitting in a bamboo thicket watching a trail.

And then there is the radio, the PRC25, the prick 25. This 23lb brick of electronics is the team’s god. It is the only reason they are alive. The RTO radio telephone operator carries it along with spare batteries. If the radio dies, the team is dead. It is that simple. There is no backup.There are no cell phones. There is only the hiss of static and the hope that the relay station on a distant mountain can hear your whisper.

The weight distribution is a calculated gamble. They carry hundreds of rounds of 5.56 mm ammunition, far more than a line infantryman. They carry claymore mines, lots of them. The claymore is the great equalizer. It is a curved plastic box filled with C4 explosive and hundreds of steel ball bearings.

When detonated, it sends a fan of steel shredding through the jungle at supersonic speeds. For a six-man team, claymores are their artillery. They set them up every night around their Ron remain overnight sight. If they are compromised, the claymores buy them the 10 seconds they need to break contact and run.

But carrying the gear is only half the battle. The insertion itself is a masterclass in deception. The helicopter pilots who fly LRPS are some of the craziest, most skilled aviators in the war. They know that dropping six men into the middle of an NVA sanctuary requires theater. They use the false insertion technique. A flight of two Hueies will swoop into an LZ landing zone.

They will hover for a moment, maybe touch the skids down. The gunners will fire into the treeine. Then they will lift off and fly to another clearing a mile away. They will repeat this three, four, five times. The enemy on the ground listening to the rotor beats knows helicopters are landing, but they don’t know which landing drop the troops. It spreads the enemy thin.

They have to investigate five LZs instead of one. On the live drop, the team jumps, the chopper lifts, and the team freezes. This freeze is critical. It is called SLL, stop, look, listen. It allows the team to acclimate. The human brain filters out background noise. In the city, you don’t hear the traffic.

In the jungle, you have to relearn what background is. You have to learn the difference between the wind moving a palm frond and a foot moving a palm frond. The difference is rhythmic. Nature is chaotic. Humans are rhythmic. A man walking has a cadence. Crunch, crunch, crunch. An animal moves in bursts.

The LRP soldier tunes his brain to the frequency of the artificial rhythm. Once the initial freeze is over, usually after 10 to 15 minutes of heart pounding silence, the team leader TL gives a hand signal. A single finger rotating. Move out. They move in a file. The point man is in front. He is the eyes. He barely looks at the ground. He looks through the brush, watching for trip wires, for disturbed vegetation, for the glint of metal.

The team leader is second, navigating with a map and compass, counting paces. The RTO is third, the antenna bent down to avoid snagging. The rear security is last, walking backward as much as forward, watching the trail they just left. Because the NVA are masters of tracking, they move painfully slow. A LRP team might cover only 500 meters in an entire day.

They take a step, wait, listen, take another step. They avoid trails like the plague. Trails are where the mines are. Trails are where the ambushes are. They bust brush, cutting their own path through wait a minute vines and bamboo that tears at their skin and clothes. But why? Why go through this torture? Because of the intelligence gap.

By 1968, the American command realizes that the body counts are lying. The destroyed units keep reappearing. The NVA are moving staggering amounts of material down the Ho Chi Min Trail. trucks, rockets, artillery pieces right under the nose of American air superiority. They are doing it by using the jungle as a roof. The LRPS are the solution to the roof.

You can’t see through the roof from a jet at 20,000 ft. You have to be under the roof. The mission profile typically falls into one of three categories: area reconnaissance, point reconnaissance, or surveillance. Area recon is a search mission. The team is given a grid square, a 1 km by 1 km box, and told to find out what is in it.

Is there a base camp? Is there a trail network? Is there a cache? Point recon is specific. Go to coordinate 48q YC123456 and see if the bridge is still standing. Or check if the B-52 strike at this location actually killed anything. These are often the most dangerous because the enemy knows the bridge is a target. They are guarding it.

Surveillance is the classic hide and watch. The team finds a spot overlooking a trail or a river crossing. They dig in. They camouflage themselves so well that you could walk within 3 ft of them and not see them. And then they wait. They count. Three trucks headed south carrying covered cargo. Platoon of NVA Pith helmets, AK-47s, no heavy packs.

They whisper this data into the radio. The data goes up the chain. It is collated. and then the hammer falls. But there is a dark side to this utility. The LRPS are so effective that they become a priority target for the NVA. The North Vietnamese are not stupid. They know that if a six-man team is in their area, an air strike is coming. They know that thesemen are the eyes of the artillery.

So the NVA develop their own counter reconnaissance teams. They deploy trackers. They use dogs. The hunter killer dynamic shifts. The LRPS are hunting the NVA, but the NVA are actively hunting the LRPS. Let’s look at the psychology of the box. When a team inserts, they are assigned an AO area of operations for the duration of the mission, usually 5 days.

That box is their universe. No one else is allowed to fire into it without their permission. It is a no fire zone for friendly artillery to prevent fratricside. This means the team is safe from friendly fire, but it also means they are cut off from immediate help. If they make contact, they have to radio the TOC, tactical operations center, to lift the restriction, call in the fire mission, adjust the coordinates, and wait for the rounds to fly.

That process takes time. Time is the one thing a LRP team does not have in a firefight. A standard infantry firefight can last hours. Platoons maneuver, pin down the enemy, call in support. ALRP firefight usually lasts seconds or minutes. It is a violent explosion of violence. If a LRP team is compromised, they have to dump everything, the heavy rucksacks, the extra water, the food, and run.

They have to break contact. They use a technique called the Australian peel. The point man fires a magazine on full auto, then turns and runs past the rear man. The second man fires, then turns and runs. They cycle backward, creating a rolling wall of lead, buying distance. If they can’t break contact, if they are pinned down, they are in the Alamo scenario.

They form a tight perimeter, usually a small circle. They blow their claymores. They get on the radio and scream prairie fire, the code word for emergency. We are being overrun. Prairie fire clears the airwaves. Every aircraft in the sky is diverted to their location. Fast movers, jets, gunships, medevacs.

It is a summons for the wrath of God. But the wrath of God takes 20 minutes to arrive. And in those 20 minutes, six men have to hold off a hundred. This is the setup. The board is dressed. The pieces are in motion. The team is on the ground. The helicopter is gone. The silence has settled. Now we zoom in.

We go from the doctrine and the equipment to the sweat and the fear. We go to the second day of the patrol where the reality of the jungle begins to rot the resolve of even the best soldiers. November 16th, 1966. Run 9ine hours. The central highlands. The team has been moving for 14 hours. They have covered perhaps 600 m. The jungle here is not a forest.

It is a vertical wall of bamboo and wait a minute vines. The vines have thorns that hook into flesh and fabric, tearing silently. You don’t walk through it. You swim through it. The heat is suffocating. It is 95° with 98% humidity. The air is so thick you feel like you are breathing soup. Sweat doesn’t evaporate. It just pools.

It runs into the eyes, stinging. It soaks the crotch, the armpits, the socks. Immersion foot, trench foot, is a constant threat. The skin turns white and pruny, then cracks, then rots. LRPS carry extra socks in waterproof bags and they change them religiously even if it means taking a boot off in a danger zone.

But the physical misery is secondary to the mental strain. The pucker factor. Every step is a calculation. Is that a vine or a trip wire? Is that a shadow or a bunker slit? Is that smell rotting vegetation or newok mom fish sauce? The NVA smell different. Their diet of fish and rice, their specific tobacco creates a scent profile that is distinct from the American smell of red meat and dairy.

A good point man can smell the enemy before he sees them and the enemy can smell them. Americans weak. They smell of soap, of gun oil, of insect repellent. The standard issue bug juice is so pungent it burns the nose. LRPS stop using soap 3 days before a mission. They don’t use bug juice. They let the mosquitoes bite.

They eat garlic to mask their scent. They try to become the jungle. But the jungle is not neutral. It is hostile. Leeches drop from the leaves. They are small thread-like worms that detect heat. They attach to the neck, the wrists, the ankles. They inject an anti-coagulant and feast until they are bloated, bloody grapes. You can’t pull them off.

The head stays in and causes infection. You have to burn them off with a cigarette or use a drop of repellent. But you can’t smoke and repellent smells, so you just let them feed. You feel the trickle of blood running down your neck and you do nothing. You stay still. The team stops for a short halt. They don’t sit. They take a knee. They face outward.

The RTO checks in. He keys the handset twice. Click click to break squelch. The TOC acknowledges. Click. No words. Words carry. The silence is the shield. This is the rhythm of the development. It is a slow grinding tension. It is boredom punctuated by moments of sheer terror. Consider the tiger story, not the animal, though they are there too.

Butthe tiger force concept or the specific dangers of the one and first airborne’s LRPS operating in the a sha. One anecdote from a first cav LRP named Doc illustrates the surreal proximity of the enemy. They are set up in a bamboo thicket watching a trail intersection. It is raining, a monsoon downpour that deafens everything. The rain is good. It covers sound.

It drives the mosquitoes away, but it also blinds you. Doc is on watch. He sees movement. A figure walks down the trail, not 10 ft away. It is an NVA soldier. Weapons slung over his shoulder, walking casually. He is wearing a poncho. He stops. He is right in front of Doc. The NVA soldier pulls down his pants and squats.

He is taking a dump right in the kill zone of the ambush. Doc has his M16 trained on the man’s chest. He releases the safety click. The sound is lost in the rain. The dilemma. Do you shoot? If you shoot, you kill him. Easy. But is he alone? Is he the point man for a regiment? If you fire, you reveal your position.

You have just traded your invisibility for one dead enemy. The math doesn’t work. The mission is reconnaissance, not attrition. Doc holds his fire. The NVA soldier finishes, pulls up his pants, and walks away. The team stays frozen for another hour. Then a column of 200 NVA soldiers walks past. They are chatting, smoking, their weapons slung.

They are completely unaware that six Americans are watching them from 10 ft away. This is the development phase of the story. The realization that the enemy is not a faceless horde, but men who poop, smoke, and talk. The realization that the LRRP is a voyer in the house of death. We need to talk about the data, the exchange ratio.

In conventional infantry units, the kill ratio might be 10 to one. For every American killed, 10 enemy soldiers die. That number is inflated, disputed, and often a lie. But in the LRP units, the confirmed kill ratio, often verified by follow-up BDA bomb damage assessment flights, is staggering. Some units report ratios of 50 to1 or higher.

Why? Because they initiate contact on their terms. or more accurately, they bring the massive firepower of the US military to bear with pinpoint accuracy. A LRP team calls in an air strike on a base camp. Four F4 Phantoms drop 500 lb Snakeey bombs in Napal. The camp is erased. The LRP team confirms 100 KIA. The team takes zero casualties.

This efficiency makes them the force multiplier. A division commander with 10 active LRP teams effectively controls 10 times the ground of a blind commander. But the data hides the human cost of the compromised missions. Let’s look at the gray zone. The twilight, the time when the LRP team has to ron remain overnight.

Night in the jungle is a different world. The darkness is absolute. You cannot see your hand in front of your face. You hold on to the man in front of you by his rucksack strap. When they stop to sleep, they don’t set up tents. They don’t use sleeping bags. They lay on the ground in a wagon wheel formation. Feet in the center, heads out. They sleep in shifts.

50% alert. Three men sleep. Three men watch. The claymore watch. You have the clacker, the detonator in your hand. You squeeze it gently just to make sure it’s there. You listen to the jungle breathing. Every snap of a twig is a potential attack. The hallucinations start after day three. The lack of sleep, the dehydration, the constant adrenaline dump creates phantom movement.

You see shadows detach themselves from trees. You see faces in the leaves, and sometimes the faces are real. November 17th, 1966, 14 hours, Quantum Province. The transition from hunter to prey is not a sudden event. It is a slow, creeping realization like the onset of a fever. It starts with a feeling. the hair on the back of the neck standing up.

A primitive biological alarm system that predates the M16 by a million years. Then it becomes sensory. The point man stops. He doesn’t raise his hand. He just stops. The team behind him freezes in a chain reaction like rail cars bumping into one another. The point man is looking at a patch of mud on a game trail they are crossing.

In the mud, there is a footprint. It is fresh. Water is still seeping into the depression, meaning it was made less than two minutes ago. But it is not the footprint of a combat boot. It is the footprint of a Ho Chi Min sandal, a sole cut from a discarded tire held on by inner tube straps, and next to it, the distinct clawed print of a dog.

The equation shifts instantly. The team is no longer the predator in the ecosystem. They have been acquired. To understand the severity of this moment, we have to look at the enemy’s evolution. In 1965, the NVA were often taken by surprise by American air mobility. By 1967, they have adapted. They understand the LRP doctrine.

They know that the Americans operate in small teams. They know that these teams are the eyes for the B-52s. Therefore, blinding the Americans becomes a strategic priority. The NVA deploys specialized counterreonnaissanceunits. These are not conscripts pulled from a rice patty in the north. These are Bush experts.

They move faster than the Americans. They carry less gear. They know the terrain because they live in it. And they use dogs. The dog is the LRP’s nightmare. You can hide from a man. You can use camouflage to fool the eye. You can use noise discipline to fool the ear. But you cannot fool a nose that can detect a scent molecule at one part per trillion.

The dog smells the fear. He smells the adrenaline. He smells the salt of the sweat. Back in the bamboo thicket, the team leader, the one zero, creeps forward to the point man. They communicate with hand signals. Point man points to the track, points to his nose, rubs his face. Sign for dog. 10 nods, slashes his throat with a finger. Sign for kill it.

Then he signals 180. Eene, escape and evasion. The mission is scrubbed. You cannot recon a target when a tracker team is 2 minutes behind you. The mission is now survival. They begin to move, but the pace changes. It is no longer the slow, methodical stalk. It is a high-speed egress. They are moving fast, risking noise to gain distance.

They cut through the thickest thorns, ignoring the tears in their skin. They need to break the scent trail. They cross a stream, walking upstream for 200 meters to wash the scent away, then exiting on a rocky shelf where they leave no footprints. It is a classic textbook maneuver taught at the mafi ricondo school in Natrang.

Let’s talk about that school for a moment. The Ricondo school is the University of the Jungle. It is a 3-week course designed to turn infantrymen into ghosts. They teach you to repel from a helicopter. They teach you to call in air strikes. They teach you immediate action drills, muscle memory for panic situations.

The motto of the school is smartness and stamina. The instructors are special forces vets who have looked the devil in the eye. They drill one concept into the students above all others. Never get pinned down. A stationary LRP team is a dead LRP team. If you make contact, you explode with violence and then you vanish. But the classroom in Natrang is dry.

The chalkboard diagrams are clean. Here in Quantum, the diagram is messy. The stream is swollen. The rocks are slippery with moss. And the dog is still coming. They hear it now. A bark, distant but distinct. It echoes off the canopy. The dog has found the exit point from the stream. The one zero checks his map.

They are three clicks kilome from the nearest potential LZ. Three clicks in triple canopy jungle is a 4-hour hike minimum. They don’t have 4 hours. He makes a decision. He signals the team to stop. They are going to set a hasty ambush. If you cannot outrun the tracker, you have to kill the tracker. They find a section of the trail that bends sharply around a massive mahogany tree. It is a natural choke point.

The team splits. Three men go to one side of the trail, three to the other, forming an L-shaped kill zone. They slide into the vegetation. They pull the safety pins on their claymores, but keep the clackers in their hands. They check their weapons. Selectors switch from safe to semi or auto. Now the waiting begins.

This is the hardest psychological test. The adrenaline dump is massive. The heart rate spikes to 160 beats per minute. Fine motor skills degrade. You get tunnel vision. The auditory exclusion kicks in. You might not even hear your own gunfire. The sounds of pursuit get closer. The NVA are not being quiet. They think the Americans are running.

They are confident. They are rushing to close the gap. First, the dog comes around the bend. It is a German Shepherd, lean and wolflike. It has its nose to the ground. It stops. It lifts its head. It looks directly at the bush where the point man is hiding. It growls. Behind the dog, the handler appears.

He is wearing a pith helmet and carrying an AK-47. Behind him, two more soldiers. The point man doesn’t wait for the signal. He initiates. Thwack. The sound of an M16 round hitting flesh is distinctive. It is a wet slap. The dog drops. The jungle explodes. Clack, clack, clack. The claymores are detonated. Three explosions merge into one concussive roar.

The blast wave shreds the vegetation. Thousands of steel ball bearings scour the trail at chest height. The foliage vanishes, turned into green mist. Immediately following the blast, 616s open up on full automatic. This is the mad minute. Although it rarely lasts a minute, it is 5 seconds of unadulterated fury. Each man dumps a 20 round magazine into the kill zone. That is 120 rounds of 5.

56 mm tumbling ammunition saturating a space the size of a living room. The noise is physical. It punches you in the chest. The smell of cordite is instant and overwhelming. Cease fire. Cease fire. The one zero screams, his voice cracking. The shooting stops. The silence rushes back in, ringing in their ears.

Smoke drifts lazily through the kill zone. On the trail, there isnothing but carnage. The handler and the two scouts are gone, erased by the claymores. The dog is dead, but the victory is a trap. The gunfire has just broadcast their position to every NVA unit within 5 miles. The scouts were just the fingertips of the hand. Now the fist is coming. Move, move, move.

The team is up and running. They don’t check the bodies. They don’t look for intel. They run. They engage the E and E protocol. They are no longer avoiding trails. They are sprinting down them, gambling. That speed is more important than stealth. The RTO is screaming into the handset. Granite, this is Rover 22.

Contact. Contact. Three. Enemy KIA. We are blowing the zone. Request immediate extraction. Over. The radio crackles. Rover 22. This is Granite. Copy. Contact. Extraction assets are inbound. E20 mics. Proceed to checkpoint Bravo for pickup. Over. 20 minutes. Two mics. It might as well be 20 years. This is where the system comes into play.

The pilot in the slick transport helicopter is sitting on the tarmac at the fire base, maybe drinking a lukewarm coke, playing cards. The scramble horn goes off. He drops the cards. He runs to the bird. The engine spools up. The rotors turn in the air. The pink team is diverted. A pink team consists of a loach OH6 Caillus, a small egg-shaped observation helicopter that flies low and fast, and a Cobra AH1G, the dedicated gunship, a shark-like machine loaded with rockets and a minigun.

They are the guardian angels of the LRPS, but they have to get there. On the ground, Team 22 is running into a wall. As they push toward checkpoint Bravo, a clearing on a ridgeeline suitable for a helicopter, they hear it, not behind them, in front of them. Signal shots. Pop, pop, pop. Three shots from an AK-47, answering shots from the left, answering shots from the right.

They are being boxed. The NVA are using the sound of the firefight to triangulate. They are moving parallel to the team, racing to cut them off before they reach the clearing. The one zero halts the team. He is panting, his face stre with mud and sweat. He looks at his compass. He looks at the terrain. They’re cutting us off at the ridge, he whispers. We can’t make Bravo.

This is the turning point. The plan has failed. The backup plan has failed. Now they are improvising. We head for the river, he says. We call for the extraction on the sandbar. It is a desperate move. The river is lower ground. It is disadvantageous tactically, but it is the unexpected move. They veer off the trail, sliding down a muddy ravine, crashing through bamboo.

The RTO is dragging the antenna, trying to keep a signal. Granite. Change of mission. LZ Bravo is hot. We are moving to LZ Sierra. The river coordinates to follow. The fog of war descends. The pilot is confused. Rover say again, LZ Bravo is compromised. Affirmative. We have movement on three sides. We’re taking fire.

Bullets begin to snap through the leaves above their heads. The NVA have made visual contact. The crack thump of the rounds passing the sound barrier tells you they are close. If you hear the crack before the thump, the bullet missed you. If you don’t hear anything, you’re dead. The team reaches the riverbank. It is a wide, muddy river, brown with silt.

There is a sandbar, maybe 30 m long, exposed in the center. Get on the bar perimeter. They splash into the water, waiting waist deep, struggling against the current. They scramble onto the sand. There is no cover here. They are six men lying prone on a flat white stage surrounded by a coliseum of green jungle. The NVA reached the treeine.

They set up RPD machine guns. The water around the sandbar begins to boil with impacting rounds. The RTO is lying on his back. The handset keyed. Previously, previously we are taking effective fire. Get the snakes in here now. And then the sound of salvation. It is a low thumping vibration that you feel in your teeth before you hear it.

Whoop! Whoop! Whoop! Whoop! The cobra! It comes in low over the river, a dark silhouette against the gray sky. It doesn’t hover, it dives. The nose points down. The sound of a minigun is not a rat tat. It is a buzzr. A stream of red tracer fire like a laser beam connects the nose of the helicopter to the treeine. The jungle erupts.

Branches are sheared off. Earth is churned up. The RPD stops firing. Rover, this is Snake Lead. I have you in sight. Keep your heads down. I’m going to make it rain. The cobra pulls up, banks hard, and rolls in for a rocket run. Whoosh! Whoosh! Whoosh! Whoosh! The 2.75in! Rockets slam into the jungle.

Secondary explosions bloom, orange fireballs rolling up through the canopy. For a moment, the team on the sandbar is safe. The overwhelming firepower of the US air asset has suppressed the enemy. This is the macro, meaning the micro. Millions of dollars of aviation technology focused on savings six lives. But the extraction ship, the Slick, is still 2 minutes out. And the NVA are not gone.

They are digging in. They are bringingup mortars. The one zero looks at his men. They are shivering, not from cold, but from shock. Their eyes are wide, the pupils dilated to pinpoints. They are checking ammo. “Check your magazines,” he yells over the roar of the gunship. “Save two for the breakout.

Don’t run dry. One of the men, a kid named Miller, is staring at his leg. There is a dark stain spreading on his tiger stripes. He’s been hit. He didn’t even feel it. The adrenaline masked the pain. Now, as the shock wears off, the pain arrives. He starts to moan. The medic, every LRRP, is trained in advanced first aid, but usually one guy is the doc.

Crawls over. He rips the pant leg open through and through on the thigh. Missed the artery. You’re good, Miller. You’re good. Walking wounded. Miller nods, gripping his rifle until his knuckles are white. The slick appears. It is a UH1H, the workhorse. It comes in fast, flaring hard over the sandbar, kicking up a storm of water and sand.

The door gunners are firing over the heads of the team, suppressing the tree line. Go, go, go. This is the reverse of the insertion. There is no grace. There is no order. It is a scramble for life. They drag Miller. They throw the rucks sacks on or leave them. It doesn’t matter now. They dive onto the floor of the helicopter, piling on top of each other. The pilot pulls pitch.

The engine screams. The bird is heavy, sluggish. It lifts, turning, gaining speed. As they clear the treetops, the RTO looks out the door. He sees the jungle below. He sees the smoke rising from the rocket strikes. He sees the river and he sees the muzzle flashes, hundreds of them. The entire riverbank is lighting up.

The NVA weren’t just a squad. It was a battalion. They had walked into the staging area of a massive offensive. The floor of the helicopter shutters. Thwack. A round punches through the thin aluminum skin of the fuselage, missing the fuel cell by inches. We’re taking hits. We’re taking hits. The door gunner screams.

The pilot noses the bird down to gain air speed, trading altitude for velocity. They are running the gauntlet. Inside the cabin, the six men are a tangle of limbs, mud, and blood. They are alive, but the mission is a failure. They didn’t get the intel. They lost the element of surprise and they have revealed their presence. But as the adrenaline fades, a different realization sets in.

The one zero looks at the map. He is still clutching. He looks at the concentration of enemy fire. They just escaped. They did get the intel. They found the enemy. They found all of them. The development phase ends here, not with a resolution, but with a revelation. The micro anecdote of the dog in the ambush has zoomed out to reveal a macro truth.

The enemy is massing. The valley is full. The silence was a lie. This leads us to the pivotal question. Why? Why are they massing here? Why now? The answer lies in the logistics. The cause and effect chain. The NVA are not just sitting in the jungle. They are building a road. A literal road capable of supporting trucks hidden under the canopy.

The LRP team didn’t just stumble into a unit. They stumbled into a strategic artery. And now the US machine is going to react. The six men were just the trip wire. Now comes the sledgehammer. But before the sledgehammer falls, we need to understand the cost of that trip wire. We need to look at the psychological toll.

The thousand-y stare isn’t a metaphor. It’s a physiological response to overstimulation of the sympathetic nervous system. Back at the base, the team falls out of the chopper. They are deaf. They stink of fear in swamp water. They are shaking. They walk past the clean, starched uniforms of the rear echelon troops, the clerks, the cooks, the officers.

The contrast is jarring. Two different wars on the same planet. They go to the debriefing. An intelligence officer smelling of aftershave asks them to point to the map. Where were they? The one zero, his hands still covered in the mud of the riverbank, points to the entire valley. Everywhere, he says. They are everywhere.

This sets the stage for the climax. The intel provided by team 22 is about to trigger a B-52 ark light strike, a box of destruction 3 km long and 1 km wide. We are about to see the industrial scale of death that follows the intimate terror of the patrol. We will see the inversion. The LRPS were the hunted. Now the NVA will be the harvested. November 18th, 1966.

5:30 hours. Anderson Air Force Base, Guam. While Team 22 sleeps the chemically induced sleep of the exhausted in a canvas tent in Quantum, the consequences of their terror are taxing onto a runway 2500 m away. This is the climax of the LRP equation. The six men in the jungle were the input. This is the output.

It is a cell of 3B52D strata fortresses called sign ark light. These are not the sleek tactical fighters like the Phantom or the Cobra. These are dinosaurs of the Cold War converted into dump trucks for high explosives. Each aircraft carries108 bombs, 84 500 lb MK82s inside the belly and 24 750lb M117s on the external pylons.

That is roughly 60,000 lb of ordinance per plane for a cell of three. That is 180,000 lb of death. The pilots in the B-52s do not see the jungle. They do not see the mud or the leeches. They fly at 30,000 ft in the stratosphere where the sky is a dark bruising purple and the temperature is 50° below zero. They are flying a math problem.

The coordinates provided by the 10, the grid square where the NVA battalion was massing near the river, have been processed, triangulated, and fed into the bombing computer. The flight takes hours. It is boring. Coffee from thermoses, box lunches, the gentle hum of eight Prattton Whitney engines. It is the benality of destruction. 125 hours.

The river valley on the ground. The NVA battalion is still there. They are celebrating the victory of the previous day. They chase the Americans away. They hold the ground. They are repairing the bunkers, cleaning their weapons, cooking rice. They feel safe. They have not heard any reconnaissance planes.

The sky is gray and empty. The jungle is noisy. Birds, monkeys, the wind. Then the world ends. There is no warning, no scream of a falling bomb. The physics of terminal velocity mean the explosives arrive before the sound of their passage. The first bomb strikes the center of the bivoac area. It detonates with a velocity of detonation of 26,000 ft pers.

It turns steel casing into razor sharp fragments and expands the air around it so violently that it creates a vacuum. But it is not one bomb. It is 324 bombs arriving in a train that is 1 km long and half a kilometer wide. The ground ripples. From the perspective of a survivor on the periphery, it looks like the earth itself is boiling.

The trees, 100-year-old mahogies, teak, ironwood, are not broken. They are atomized. They are turned into splinters the size of toothpicks. The overpressure wave moves at supersonic speed, liquefying internal organs, collapsing lungs, and shattering eardrums of anyone within a thousand meters who is not underground. The sound is not a boom.

It is a continuous rolling thunder that lasts for 45 seconds. It creates a seismic event that registers on seismographs in Saigon. Inside the box, the temperature spikes to thousands of degrees. The oxygen is sucked out of the air to feed the fireballs. And then silence returns. But it is not the heavy living silence of the jungle.

It is a dead silence. The birds are gone. The monkeys are gone. The wind is gone. replaced by a rising column of smoke and dust that punches through the cloud deck and rises to 40,000 ft. November 19th, 1966 08 hours. The aftermath. The cycle completes itself. The giant is blind again.

It has swung the hammer, but it does not know if it hit the nail. It needs eyes. Team 22 is not going back. They are combat ineffective due to exhaustion. But another team, team 46, is inserted. The mission is BDA bomb damage assessment. They insert into the edge of the crater field. The LZ is easy to find now. The jungle has been erased.

They jump from the helicopter into a landscape that looks like the SA in 1916 or the surface of the moon. The soil is churned, soft, and gray. It is mixed with ash. There are no landmarks. The map is useless because the terrain features, the trails, the stream, the hillock have been rearranged by high explosives. The stench is unique.

It is the smell of pulverized wet wood, cordite, and something sweet and copper-like. Death. The team moves through the devastation. They do not need to be quiet. There is no cover to hide in, and likely no one left to hear them. They count. This is the grim accounting of the war. They count bodies. They count pieces of bodies.

They count destroyed weapons. One heavy machine gun wheel destroyed. Three enemy KIA partial remains. bunker complex collapsed. They find a survivor, an NVA soldier, sitting on the edge of a crater. He is not wounded in the conventional sense. He has no shrapnel holes, but he is bleeding from his nose and ears.

His eyes are open, staring at the sun, but he is blind. His brain has been scrambled by the concussion. He does not move when the Americans approach. He is a statue of shock. The team leader of 46 radios it in. Granite, this is Rover. Target destroyed. Estimate battalion strength element neutralized. Secondary explosions confirm ammo cache.

It’s a parking lot down here. Over. This is the success. This is the validation of the LRP concept. Six men risk their lives to guide a hammer that destroyed 600. The exchange ratio is efficient. The system works. Part four. The ghost in the machine resolution. But does it work? Let’s zoom out to the resolution. The year turns. 1966 becomes 1967.

1967 becomes 1968. The NVA battalion destroyed in the valley is replaced. New recruits come down the trail. The craters fill with water and become ponds. The jungle, aggressive and relentless, begins to grow back. In 6months, the scar is covered in green. In a year, the trail is active again. The LRPS continue to go out.

The danger does not decrease. It evolves. The enemy adapts to the B-52s. They dig deeper. They move in smaller groups. They hug the American belts even tighter. The toll on the LRP soldiers accumulates. It is not just the physical danger. It is the psychological burden of being the Judas goat. You go in, you find them, you call down the fire, and you leave.

You are the architect of invisible destruction. The men of team 22 finish their tours. They go home. They return to a country that is indifferent or hostile. They take off the tiger stripes and put on denim. But the isolation follows them. You cannot explain the feeling of the box to a civilian. You cannot explain the intimacy of the jungle silence to someone who has only known the noise of the city.

You cannot explain the morality of watching a man take a dump and deciding whether or not to end his universe. The development of the soldier continues long after the war. The hyper vigilance remains. The LRP veteran sits in a restaurant facing the door. He scans the perimeter. He notices the guy leaving a bag unattended.

He hears the specific pitch of a siren before anyone else. He is still in the box. The systemic outcome of the LRP program is a paradox. Tactically, they were the most effective units in the war. They inflicted more damage per man than any other element. They saved countless American lives by detecting ambushes before they happened. But strategically, they were a band-aid on a hemorrhage.

You can find every enemy soldier in Vietnam. But if the political will and the strategic framework are flawed, the intel is just data. The body count becomes a metric of success that ignores the reality of the will to fight. The NVA were willing to absorb the B-52 strikes. They were willing to die in the craters. The Americans were not willing to stay in the jungle forever. Part five. Epilogue.

July 4th, 1995. A suburban backyard in Ohio. The one zero from teamed 22 is now an old man. He is grilling hamburgers. His grandchildren are playing with sparklers on the lawn. The air is filled with the smell of charcoal and cut grass. A firework goes off in the distance. Thump. For a microcond. The old man is not in Ohio.

He is on the sandbar. The water is boiling with bullets. The cobra is diving. The smell of the river is in his nose. His heart hammers against his ribs. He blinks. The image fades. He flips a burger. Grandpa, are you okay? One of the kids asks. He smiles. It is a practiced tight smile. I’m fine, kiddo. Just thinking.

He is thinking about the silence. The silence of the moment after the helicopter leaves. The silence of the jungle waiting to kill you. And the silence of the crater field after the wrath of God had passed. He looks at the trees at the edge of his yard. Maple and oak, they are safe. There are no wires. There are no snipers.

But he knows with a certainty that chills his blood that safety is an illusion. The world is a thin membrane stretched over chaos. He has seen what is underneath. He has been the needle that pierced the membrane. Outro date unknown. The a valley present day. The wind is blowing through the canopy. The bomb craters are still there.

Soft depressions in the earth now covered in ferns. The rusted remains of a canteen cup sit half buried in the mud. The war is history. The politics are forgotten. The tactics are studied in manuals. But the principle remains. War is often depicted as a clash of armies, a collision of fronts. But at its sharpest point, at the tip of the spear, it is not an army.

It is just a few men alone in the dark, waiting for a sound that doesn’t belong. It is the isolation that defines the courage. It is not the bravery of the charge with bugles blowing and flags waving. It is the bravery of the statue. The bravery of holding your breath while a predator walks past your face.

The bravery of being the only thing standing between the giant and the abyss. They were the eyes of the machine, but they paid for the vision with their souls.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.