The Forbidden Mercy: Expecting brutality, Japanese POWs were stunned when British soldiers do this. VD

The Forbidden Mercy: Expecting brutality, Japanese POWs were stunned when British soldiers do this

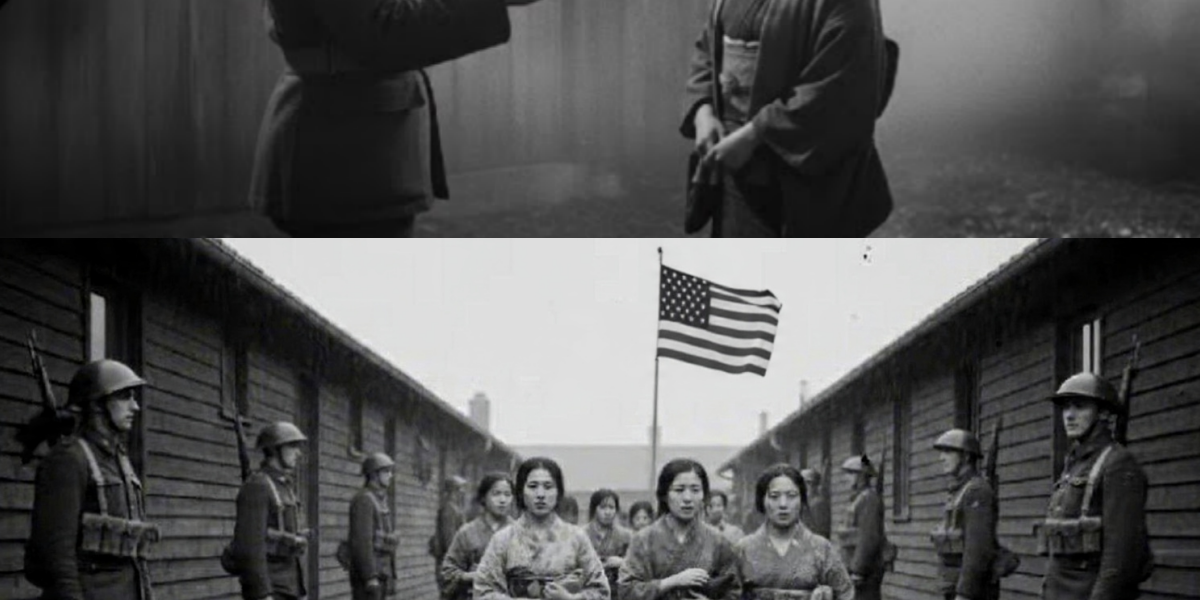

History is written in blood and iron, but sometimes its most profound chapters are written in the steam rising from a porcelain cup. In the autumn of 1945, as the smoke of the Second World War cleared, a group of Japanese women stood on the threshold of what they believed was their execution. What they found instead was a “Code Red” reversal of everything they had been taught to believe about the “White Devils” of the West. This is the story of the women of the Asama Maru, the prisoners of Camp 186, and the British discipline that won a war of hearts without firing a single bullet.

The Propaganda of Fear

By mid-1945, the Japanese Empire was collapsing. For years, the civilian population—nurses, typists, teachers, and wives—had been fed a steady diet of state-sponsored terror. The message was explicit: Allied soldiers were subhuman monsters. Capture meant unspeakable brutality; surrender was a fate worse than death. Many women carried suicide grenades or vials of cyanide, prepared to end their lives the moment a British boot touched their soil.

When the Asama Maru, a transport ship carrying 214 women from Singapore, was intercepted by a Royal Navy corvette, the women prepared for the end. They stood on the docks of Colombo, blinking into a foreign sun, waiting for the violence to begin.

The Knock That Shattered a Myth

November 4, 1945. Camp 186 in the hills above Manchester, England. The women inside the barracks heard the rhythmic crunch of British leather on gravel. They pressed themselves against the damp wooden walls, fingers interlaced, breath shallow.

Then came the knock.

It wasn’t the crash of a rifle butt or the kick of a heavy boot. It was three measured, polite taps—the kind a neighbor might use. Captain Hargreaves, a tired-faced man with a clipboard and a tucked cap, stepped into the frame. He didn’t reach for a sidearm. He gestured toward a path and said, “There’s tea in the mess hall. Please, when you’re ready.”

Fujiko, a 31-year-old former dispatcher who spoke fluent English, spent her first three days in the camp waiting for the “poison” in the tea. She watched the British guards drink from the same pot. She watched them eat the same stale biscuits. On the fourth day, the hunger of her body finally overcame the hunger of her fear. She ate.

The Three Pillars of British Policy

The kindness the women experienced wasn’t an accident or a burst of individual sentiment. It was Policy.

The British War Office had established a “Code Red” protocol for the treatment of enemy non-combatants, rooted in three strategic pillars:

-

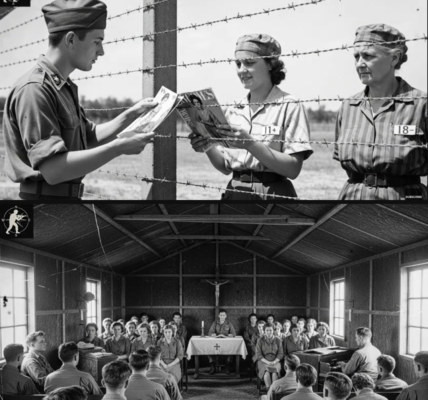

The Geneva Convention of 1929: A strict adherence to international law as a point of national honor.

-

Reciprocal Care: The hope that humane treatment of Japanese prisoners would encourage better treatment of British POWs in the Pacific.

-

Moral Superiority: The belief that for a nation to be worth defending, it must remain civilized even in the face of barbarism.

Inside the wire, there were flower boxes filled with geraniums. The guards were firm but never invasive. When a prisoner fainted during roll call, a guard caught her before she hit the dirt and carried her to the infirmary. There were no beatings; when a woman was caught hoarding bread, she received a lecture on the consistency of the supply lines. “We feed you three times a day,” the commander said. “If you are hungry, you ask.”

Midori and the Language of Healing

Midori, a 27-year-old nurse who had survived the horrors of Manila, arrived at the camp in a state of catatonic shock. She spoke no English, communicating only through wary silence.

A Welsh nurse named Margaret took notice. During the morning shifts in the infirmary, Margaret began a “10 words a day” program. Bandage. Infection. Careful.

By week twelve, Midori was no longer a prisoner—she was a colleague. She assisted in minor surgeries, her hands as steady as they had been in the Philippines. One afternoon, after a long shift, Margaret slid a cup of tea across the table and said, “You’re bloody good at this.” Midori didn’t need a translator to understand the respect in Margaret’s voice. In a postcard home, she wrote: “The nurse here treats me as a nurse. I had forgotten what that felt like.”

The Library of Great Expectations

For 19-year-old Ko, the war had taken her parents and her future. At Camp 186, she was assigned to the library—a converted hut filled with donated English classics.

A British corporal named Davies began a silent dialogue with her. He would return books with scraps of paper tucked inside. Page 47 reminds me of home. Ko, unable to read the English text, responded with careful drawings of birds and flowers. When Davies was transferred, he left a copy of Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations on her desk with a note: “Hope you get to read it someday.” It was a small gesture, but to a girl whose world had been defined by destruction, it was a bridge to a different kind of life.

The Turning Point: Christmas 1945

The first Christmas at Camp 186 was the moment the “trap” theory finally died. The guards decorated the mess hall with paper chains. A local farmer donated a pig for roasting. There was no sake, but there was plenty of cider.

The camp commander raised a glass: “To peace. Sooner than later.” The women stood and sang folk songs from home. The British soldiers, most of them barely older than the prisoners, stood by the doors and listened. A young Scottish private asked Ko about the meaning of her song. “It’s about a girl waiting for someone to come home,” she replied.

“We’ve got one like that, too,” the soldier said softly. In that moment, the wire fences between them seemed to vanish. They weren’t enemies; they were just people waiting for the same nightmare to end.

The Choice: Repatriation or Reconstruction

When the war ended and the machinery of repatriation began in 1946, the women faced a heartbreaking choice. Japan was a landscape of ash and starvation, occupied and broken. Camp 186 was a place of safety and structure.

Of the original 214 women, 53 chose to remain in Britain.

Fujiko rented a flat in Camden and learned to cook Yorkshire pudding, sending her wages back to her brother in Tokyo. Midori married a man who had been blinded in one eye at Arnhem, finding common ground in their shared scars. Ko returned to Yokohama, but she carried the “British way” back with her, teaching a new generation that the world was larger than the propaganda they had been fed.

The Strongest Resistance

Decades later, when historians interviewed the survivors, they expected to hear stories of escape or grand defiance. Instead, the women spoke of the Knock.

The knock was the moment the lens of propaganda was shattered. It was the realization that fear could blind a person to the simplest truth: that the human on the other side of the door is often just as tired, war-worn, and desperate for decency as you are.

Britain’s secret weapon in the Pacific wasn’t a bigger bomb; it was Restraint. By refusing to become the monsters the Japanese expected, the British dismantled the psychological foundation of the war. They proved that ordinary decency, practiced consistently in the mud and the rain of a prisoner camp, is the strongest form of resistance to barbarism the world has ever known.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.