Postcards from Texas (1945): Japanese POWs Shocked to Send Letters to Their Families. NU

Postcards from Texas (1945): Japanese POWs Shocked to Send Letters to Their Families

The Postcard from Texas: A Prisoner’s Awakening

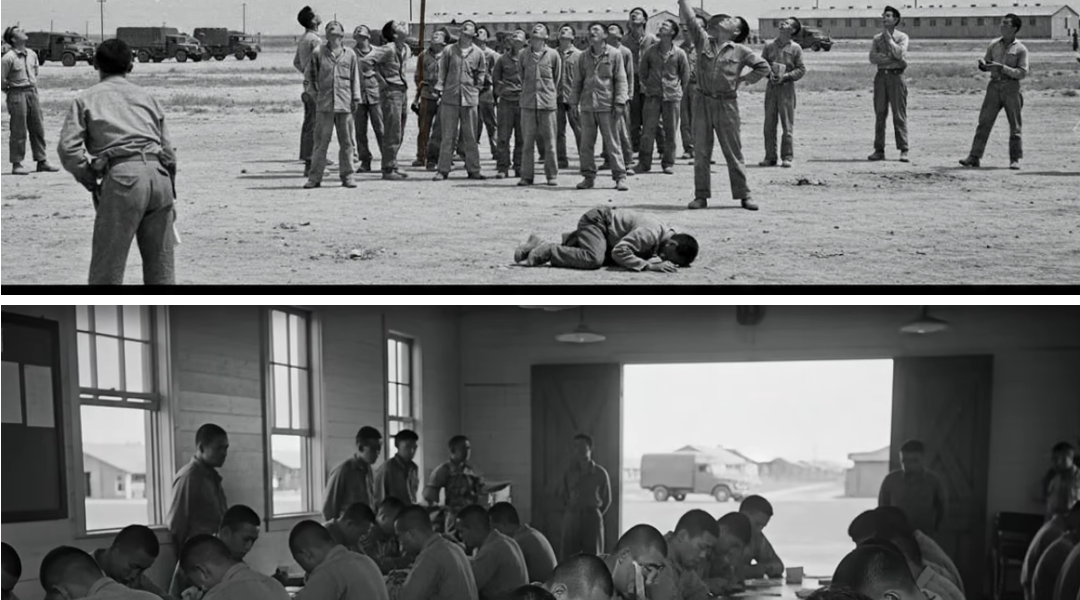

May 12th, 1945. The afternoon sun beat down mercilessly on the dusty grounds of Camp Kennedy, a Prisoner of War camp in Texas. Sergeant Teao Yoshida, a 32-year-old veteran of the Imperial Japanese Army, stood frozen in the sweltering heat, clutching a blank postcard in his trembling hands. After nearly three years as a prisoner of war, the reality he was facing now—under the care of his American captors—was not just a shock to his senses, but to his very beliefs.

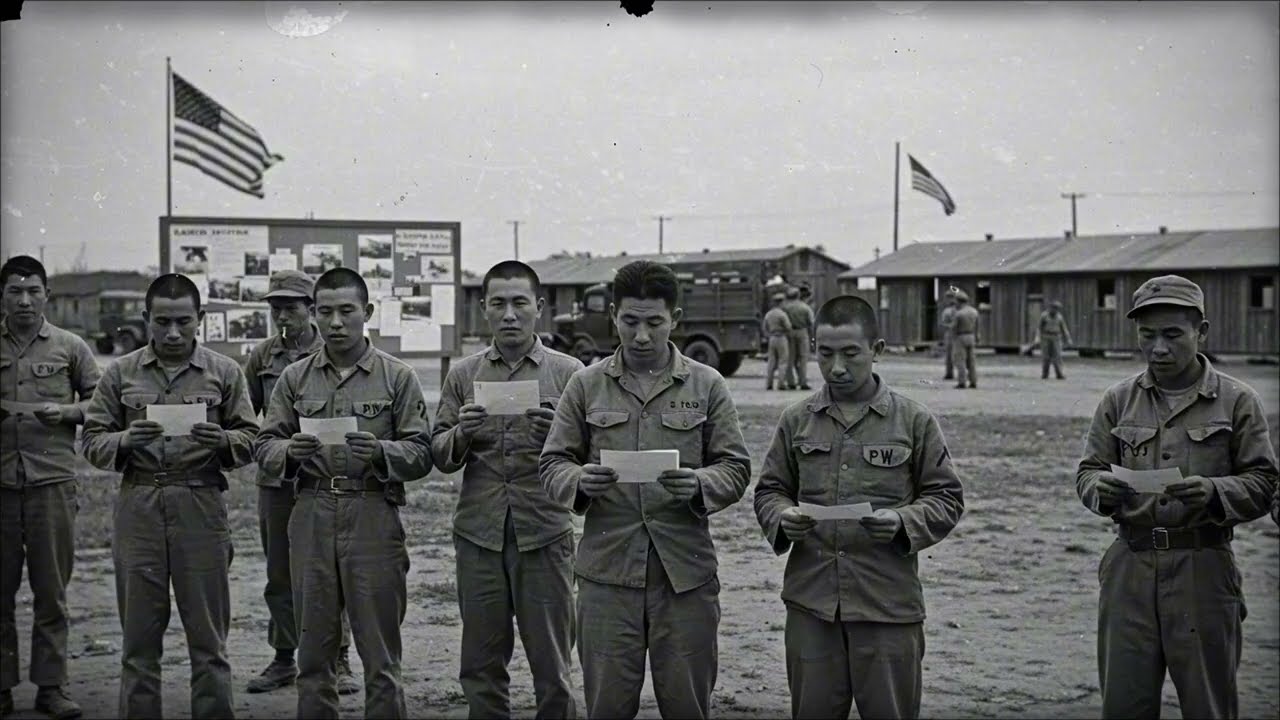

What had just happened was incomprehensible. The camp commander, Lieutenant Colonel James Morrison, had made an announcement that shook the foundation of everything Yoshida had been taught about the enemy. “Each of you will be permitted to send two postcards and one letter home each month,” Morrison said through an interpreter. The words were as casual as if Morrison were discussing a minor administrative matter, but for Yoshida and the 417 other Japanese prisoners standing in formation, the message was anything but routine.

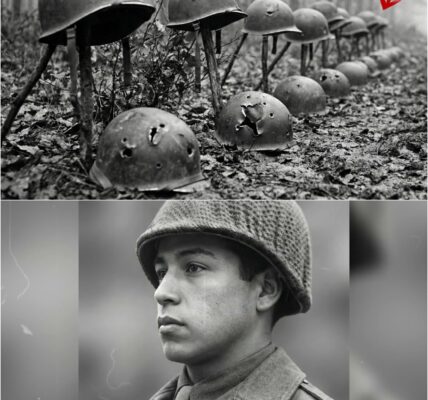

In the eyes of Japan’s military doctrine, a captured soldier was as good as dead. Surrender was the ultimate disgrace, the ultimate failure. The Imperial government would declare those captured to be dead, erasing their names from family registries. No soldier was ever meant to be allowed to communicate with his family once taken prisoner. And yet here, standing on the sun-scorched grounds of an American camp in the heart of Texas, Yoshida was told that he could send postcards—two a month—to his family.

This moment was surreal. He stared at the blank postcard in his hand, its cream-colored surface almost mocking him. To Yoshida, this was not just a piece of paper; it was a crack in the armor of the ideology he had carried with him for years. An enemy that treated its captives with respect, that allowed them to communicate with their loved ones—this was something that defied everything he had ever been taught to believe.

The Years of Indoctrination

Yoshida’s realization that his captors were not the monsters he had been taught to hate began with this simple act of permission to send a postcard. For years, Japanese military doctrine had placed the ultimate value on honor, with a heavy emphasis on death before dishonor. The famous Senjin Kun, Japan’s field service code, dictated that prisoners of war were to be considered dead, their sacrifice part of a greater purpose, and their surrender was a shame worse than death itself.

The Japanese government had created a generation of soldiers who genuinely believed that to be captured was the ultimate failure. Stories of mass suicides, such as those during the Battle of Saipan and the Banzai charges in the Pacific, were ingrained in every soldier’s mind. It was a culture of honor through death—honor through sacrifice.

And the belief in the inherent barbarity of Americans was central to this mindset. For years, the Japanese population had been taught that Americans were a morally corrupt, chaotic, and weak nation—incapable of producing anything of value, let alone waging a prolonged war. The American soldier, they were told, was a disorganized, undisciplined fighter, and the American government was incapable of sustaining a war effort.

What Yoshida and his comrades had not anticipated was the sheer scale of American military power, nor the staggering capacity of its industry to sustain that power. The American system was unlike anything they had ever imagined. It wasn’t just about fighting harder—it was about fighting smarter, with an industrial base that could replenish losses faster than they could inflict them.

The Shocking Reality of American POW Camps

As the days turned to weeks at Camp Kennedy, Yoshida was forced to confront a starkly different reality than he had been taught. The conditions in the camp were unlike anything he had expected. Instead of suffering and deprivation, the prisoners were treated with what seemed to be an overwhelming abundance. There were three meals a day, a luxury that many of the prisoners had not known since before the war. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner were regular and substantial. Eggs, toast, fruit, and even meat—something unheard of in the starving Japan that many of the men had left behind—were commonplace.

Yoshida and his fellow prisoners had been taught that American soldiers were soft, accustomed to comfort, and incapable of enduring the harshness of war. Yet, here they were, treated with respect, well-fed, and receiving care from doctors and medics with access to supplies that seemed endless. In contrast, many of the men had barely survived the war with their own country’s makeshift medical care.

The most jarring shock came when Yoshida first arrived at the camp and received his first meal. In the past, meals were rationed and often barely sufficient to keep soldiers going. Now, the food was plentiful—more than enough for even the hungriest prisoner. “I could not eat at all and asked when we would get our next meal,” Yoshida recalled in a letter to his family. “The guard looked confused and said, ‘Lunch is at noon.’”

Such regularity in food distribution was unimaginable to a man who had been raised to believe that scarcity was an inevitable part of war. In his mind, the fact that America could afford to feed prisoners like this was a sign of something far more profound than just military superiority—it was a reflection of the strength of their entire system.

The Scale of American Abundance

Beyond food, the material conditions of life in the American camps were a revelation. The barracks, which housed the prisoners, were far better than anything the men had ever lived in during the war. Wooden structures with beds, pillows, blankets, and heating systems were a far cry from the makeshift shelters they had known back home. Yoshida marveled at the comfort. “The building has heating that keeps us warm, even at night,” he wrote in a letter, his tone one of disbelief.

American prisoners received not only ample food and shelter but also regular medical care. Even minor ailments were treated with immediate attention. Yoshida had heard rumors of the brutal, uncaring American medical system, but the reality before him shattered that myth. Antibiotics, surgical instruments, and medical supplies were available in abundance. “They gave us a large glass of milk with each meal,” said Private Kenichi Morita, another prisoner. “In my village, we had not seen milk since 1941.”

The physical transformation of the prisoners was dramatic. Many, like Yoshida, gained weight, their gaunt bodies becoming more robust. The medical staff even attended to the prisoners’ dental health, something that had become a luxury back in Japan. The numbers told a striking story—Japanese prisoners gained 12 to 15 pounds during their first six months of captivity. It was a reality that could not be ignored. Here, in an American POW camp, they were living better than they had in their own homes.

The Cognitive Dissonance of War

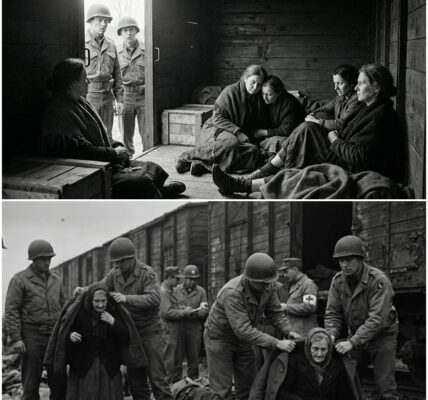

At first, many of the prisoners believed that their treatment was part of an elaborate deception, designed to lull them into a false sense of security. They were convinced that, soon, the Americans would reveal their true nature—their cruelty, their brutality. But as the weeks turned to months, it became increasingly clear that this was no trick. The abundance they were experiencing was real.

Sergeant Yoshida, a man raised on the ideals of Bushido and the honor of the Samurai, found his beliefs about war, life, and even death beginning to crumble. His worldview—one that saw death before surrender and absolute loyalty to the Emperor—was being eroded by the very system that his country had sought to destroy.

He wasn’t alone. Across the camps, prisoners began to question the very foundation of their upbringing. They had been taught that Japan was superior, that it was destined to rule Asia and defeat the West. Yet, here in America, they found a nation that operated with an efficiency and abundance that far surpassed anything they had imagined.

A New Understanding

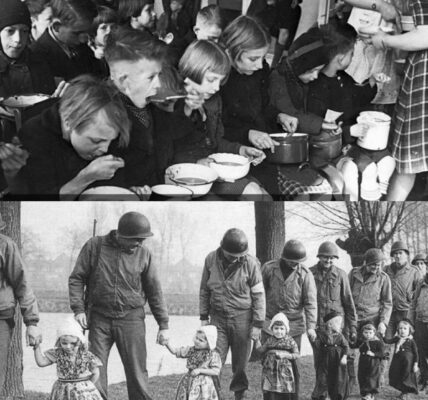

As the war neared its end, the shift in perspective among the Japanese prisoners became undeniable. They had come to America with the firm belief that the country they fought against was weak, disorganized, and incapable of sustaining a war effort. But what they saw and experienced in captivity showed them a different reality.

By the time news of Japan’s surrender reached the camps in August 1945, many prisoners had already accepted that they had been fighting a war that was lost before it had even begun. They had seen firsthand the industrial might of the United States, the scale of its production, and the generosity and efficiency with which they treated their captives. The fear, hatred, and distrust of Americans that had been ingrained in them for so long had been replaced by a grudging respect and, in some cases, admiration.

A Nation Reborn

Sergeant Yoshida, along with the other former prisoners, would return to Japan with a new understanding of what it meant to be strong—not through sacrifice and death, but through the ability to organize, produce, and provide for all people, even those who had once been enemies. The knowledge they gained in captivity would shape Japan’s future, guiding it as it moved from the ashes of defeat to becoming one of the world’s greatest economic powers in the decades to come.

The journey from death before dishonor to the embrace of industrial power and organizational efficiency was a painful one, but it was one that began with a simple postcard in the heat of Texas. That small moment of humanity, offered by the Americans, began a process of change that not only affected the men who had been captured but ultimately transformed an entire nation.

What Sergeant Yoshida once believed to be impossible—treating prisoners with dignity, abundance, and respect—became the very foundation on which post-war Japan would build its future. It was a lesson learned not through speeches or ideologies, but through the simple, everyday practices of those he had once called enemies. The strength of a nation, he would come to understand, lay not in its ability to fight, but in its ability to create, sustain, and, ultimately, to heal.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.