“Please Don’t R*pe Us” German Women Shocked When American Soldiers Didn’t Even Touch Them. NU.

“Please Don’t R*pe Us” German Women Shocked When American Soldiers Didn’t Even Touch Them

In the spring of 1945, as Nazi Germany collapsed under the weight of Allied advance, fear traveled faster than any army. For millions of German civilians, especially women, the end of the war did not mean relief—it meant dread. Years of propaganda, combined with real and horrifying stories from the Eastern Front, had shaped a single expectation: occupation would bring violence, humiliation, and sexual assault. Among the most haunting phrases whispered across ruined towns was a broken line of English learned not in classrooms, but through terror—“Please don’t rape us.”

This phrase captured the psychological state of countless German women as American troops approached from the west. Nazi propaganda had long warned that enemy soldiers were savages, while refugee accounts from territories overrun by the Red Army described mass sexual violence that left entire communities traumatized. By April 1945, these stories were no longer distant rumors. They were accepted truths, passed from mother to daughter, from neighbor to neighbor, shaping how women dressed, how they walked, and even how they prepared to surrender.

In this context, a small group of displaced German women walking toward advancing American soldiers in Thuringia represented something larger than a single encounter. They carried not weapons or demands, but fear itself. They had stripped themselves of anything that might attract attention—no lipstick, no jewelry, no belts. One carried a white cloth tied to a broken broomstick, an improvised symbol of surrender. Another quietly rehearsed four English words under her breath, not as a plea for mercy, but as a survival tactic.

What these women expected was shaped by a world already shattered. The German state had vanished overnight. Local officials had fled. The Wehrmacht had retreated. The SS had passed through and disappeared. Law, order, and authority were gone, replaced by silence and rumor. In such a vacuum, civilians assumed the worst. Power without restraint, they believed, always turned violent.

Yet when American jeeps rolled into view, something unexpected happened—nothing. There were no shouted orders, no raised rifles, no drunken soldiers rushing forward. The Americans slowed, stopped, and remained seated. They asked simple questions. Were they civilians? Did they have weapons? Did they need food? The interaction was controlled, procedural, and strikingly unemotional. No one touched the women. No one demanded anything. The absence of violence itself became the shock.

This moment marked a profound collision between expectation and reality. The women had braced themselves for assault, humiliation, or worse. Instead, they encountered discipline. American soldiers followed protocols that had been drilled into them repeatedly as the war moved into Germany. Military Police were present. Civilians were registered. Medical personnel checked for injuries. Orders were issued calmly and followed precisely. This was not kindness in the sentimental sense—it was restraint enforced by command.

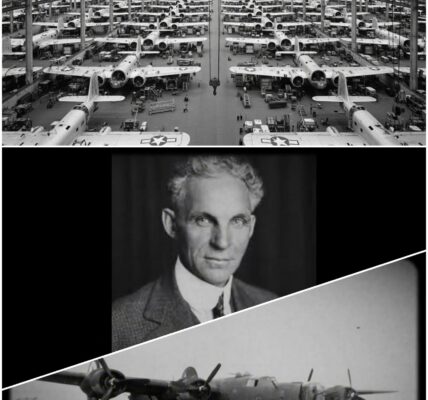

The American occupation strategy in Germany during the final phase of World War II was shaped by hard lessons learned earlier in the war. In France and Belgium, lapses in discipline had led to incidents that embarrassed commanders and undermined moral authority. By 1945, General Dwight D. Eisenhower and Allied leadership were explicit: the American Army was not an army of revenge. It was an occupying force tasked with restoring order, not indulging chaos. Rape, looting, and abuse were clearly defined as court-martial offenses, punishable by long prison sentences or worse.

For the women who encountered these troops, the system mattered more than the individual soldier. The men they saw were young, often barely out of their teens, carrying rifles and clipboards with equal seriousness. They did not flirt. They did not stare. They did not linger. Soldiers who wandered too close to civilians without purpose were ordered away by sergeants. Any unauthorized contact risked investigation. The Americans, as one woman later observed, seemed to be watching each other more closely than they watched the civilians.

This enforced distance created a strange emotional environment. The women were not abused—but they were not comforted either. They were processed, registered, fed, and monitored. They became entries in ledgers rather than objects of interest. For people who had prepared themselves psychologically for brutality, this neutrality was deeply unsettling. Trauma had been anticipated, rehearsed, and internalized. Its absence left confusion in its wake.

The American system extended beyond the first encounter. Civilians were housed in supervised locations. Guards were posted outside, not inside. Doors remained open during the day. No soldier was allowed to enter civilian quarters without witnesses and authorization. Red Cross personnel conducted interviews. Names were recorded. Complaints were invited and documented. This bureaucracy, cold and impersonal as it seemed, served a crucial function—it created accountability.

Behind the scenes, discipline was not theoretical. Soldiers accused of assault were arrested, investigated, and punished. Courts-martial were real, swift, and visible within the ranks. Dishonorable discharge and long prison sentences were not rumors; they were enforced consequences. The presence of military police, inspectors, and even journalists ensured that misconduct could not easily be hidden. Occupation was being documented in real time.

For German women, this structure sharply contrasted with what they heard from other regions. In areas first entered by Soviet troops, stories of mass rape were widespread and well-documented. Entire villages had been terrorized. The difference was not a matter of nationality alone, but of policy and enforcement. Where restraint collapsed, it was often because command structures failed or discipline was abandoned. Where it held, it was because systems remained intact.

The women who passed through American-controlled zones found themselves in an emotional limbo. They were safe, but not secure. Fear lingered, even as days passed without incident. They slept in their clothes. Shoes remained on at night. Every sound was interpreted as a potential threat. Trauma does not disappear simply because violence does not occur. But over time, something subtle shifted. Anticipation gave way to vigilance. Vigilance gave way to cautious observation.

When these women were later transferred to civilian processing centers run by Allied authorities, their experiences continued to stand out. Interviews conducted by Red Cross agents and Allied civil affairs officers asked direct questions: Had they been harmed? Had they been threatened? Had anything been taken? Many answered no. These responses did not erase the suffering of others, but they added complexity to the historical record.

In postwar sociological studies, German women repeatedly described their greatest surprise as not being harmed. This absence became a defining memory. One woman wrote that she had practiced the English phrase asking for mercy, only to never need it. Another described the American soldiers as distant, silent, and controlled—qualities she found harder to understand than cruelty would have been.

Historians examining the Allied occupation of Germany often emphasize this variance in experience. There was no single occupation narrative. Conduct differed by unit, by commander, and by circumstance. But where discipline was enforced consistently, outcomes changed. Violence did not vanish entirely, but it was contained. And containment mattered.

This story is not meant to romanticize war or absolve armies of wrongdoing. American forces were not immune to misconduct, and abuses did occur. But the presence of rules, oversight, and consequences fundamentally altered civilian experience in many places. The difference was not moral superiority—it was institutional control.

The phrase “Please don’t rape us” stands today as a symbol of what women expected war to bring. That expectation was tragically justified in many contexts. But in some encounters, like those with disciplined American units in 1945, what followed was something else entirely. Silence. Distance. Order. And the unsettling realization that violence, though possible, was not inevitable.

In the end, what these women carried away was not gratitude or trust, but a complicated memory of restraint. They had walked into the unknown expecting horror and emerged unchanged in body, if not in mind. Their story is powerful precisely because of what did not happen. In a war defined by extremes of cruelty, the absence of violence became its own historical fact.

The legacy of that restraint remains relevant today. It reminds us that systems matter, that leadership shapes outcomes, and that even in the chaos of war, discipline can alter human experience. Not by heroism or compassion alone, but by rules that are enforced when it matters most.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.