“Please Don’t Hurt Me,” She Whispered—Then an American Soldier Ripped Her Dress Open in Front of Everyone, Revealing a Reason No One Expected in War. NU

“Please Don’t Hurt Me,” She Whispered—Then an American Soldier Ripped Her Dress Open in Front of Everyone, Revealing a Reason No One Expected in War

The woman’s voice was so small it nearly disappeared beneath the wind.

“Please… don’t hurt me.”

Private First Class Thomas “Tommy” Reed heard it anyway. He heard it the way you hear a twig snap in a quiet forest—sharp, final, unmistakable. The words didn’t sound like German the way the shouted commands and barking orders had sounded all across the Rhine. They sounded like English, like someone had learned them from a phrasebook and practiced them in the dark.

Tommy froze with both hands halfway raised.

He was twenty-one and looked younger than the mud on his boots. His helmet sat a little too large on his head, and his uniform still had the stiff newness that said he hadn’t been in Europe as long as the men around him. But his eyes were tired in a way no farm boy’s eyes had ever been tired back in Iowa.

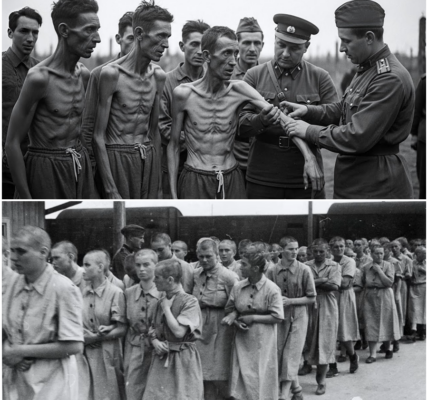

The war had been “over” for weeks, at least the shooting part. The surrender paperwork had traveled faster than the damage it described. The countryside was still broken. Bridges were still gone. Homes had roofs like open mouths. People walked with that careful, careful gait of those who had learned not to trust quiet.

Tommy stood in the courtyard of what had once been a schoolhouse and was now a temporary holding site for displaced civilians and captured stragglers—men and women who had been swept up in the chaos of retreat. The place smelled of wet stone, smoke, and old chalk.

The woman was on the other side of a crude line made of rope and two overturned desks. She wasn’t a soldier. She wasn’t wearing a uniform. She wore a faded blue dress that might have been pretty once, before the hem was muddy and the sleeves were patched with a different fabric. Her hair was pinned back, but the pins were crooked, as if she’d done it with shaking hands.

Tommy could tell she had already decided what he was going to do. Her eyes were wide, fixed on him, and her whole body was angled away, ready to flinch.

Behind Tommy, Sergeant Eddie Marlowe muttered, “Easy, Reed. Keep your posture. Don’t crowd her.”

Marlowe had the kind of face that looked carved by weather. He’d been in North Africa, Italy, France. He carried a cigarette behind his ear like it was a small flag of endurance. He also carried the unspoken authority of a man who had seen too much to pretend he hadn’t.

Tommy nodded once, barely moving.

“I’m not gonna hurt you,” he said, speaking slowly, as if each word needed to be unwrapped carefully so it wouldn’t cut her.

The woman didn’t blink. “Please,” she whispered again. “Please don’t.”

Tommy’s throat tightened.

This was not how he’d imagined victory. Back home, victory had been parades and church bells. In the newsreels it was men kissing strangers in the street. Here it was a woman terrified of his hands.

He glanced down at his hands, suddenly aware of their size, their power. They were not violent hands by nature. They were farm hands, hands that had tied hay bales, repaired fence posts, carried sacks of feed. But war had put a rifle between them and taught the world to read them differently.

Marlowe stepped closer, voice low. “Doc says there’s a rash going around in the camp. Typhus scares, lice, the works. We’re checking everyone. Quick look, quick check, move along.”

Tommy swallowed. “She doesn’t understand.”

“Then make her understand,” Marlowe said, not unkindly. “But don’t let this turn into a scene. Folks are jumpy.”

Tommy looked around. In the courtyard, other civilians watched—women holding bundles, old men leaning on canes, a boy with a too-large coat clutched around him like armor. A few American soldiers stood nearby, shifting their weight. Everyone’s eyes were hungry for meaning. Everyone’s nerves were raw.

The medics had set up a small station near the schoolhouse steps. A table with supplies. A washbasin. Bandages. Bottles of cloudy disinfectant. A young medic named Corporal Harris was wiping his hands with a cloth, his expression weary.

“Reed,” Harris called. “Bring her over. We have to check her arm. She’s been scratching.”

Tommy saw it then: the woman’s left hand kept drifting to her right forearm, rubbing through the sleeve in small frantic motions. She tried to stop when she noticed him looking, but the itch—whatever it was—seemed to own her attention.

Tommy lifted his palms again, slow.

“Medical,” he said, pointing toward Harris. “Doctor. Help.”

The woman’s eyes flicked to the medic station, then back to Tommy. She didn’t move.

Marlowe sighed. “Language barrier. Give me a second.”

He crouched, rummaged in his pocket, and pulled out a small folded pamphlet—one of those Army-issued leaflets printed in German: instructions for civilians, directions for camps, basic phrases. He opened it and pointed.

“Medizin,” Marlowe said, tapping the word.

The woman stared. Her gaze fell on the printed letters, then on Marlowe’s mouth. She swallowed.

“Medizin,” she repeated, like trying the shape of it. “Ja.”

Tommy exhaled, relieved.

“Okay,” he said softly. “Come.”

She took one hesitant step, then another, as if the ground might punish her for choosing. Tommy kept his distance, walking alongside, not in front, like he’d learned with skittish horses back home.

At the medic station, Harris motioned her to sit on a stool. She did, stiff-backed, hands clenched in her lap.

Harris pointed to her sleeve. “I need to see your skin,” he said, then looked at Tommy. “Tell her.”

Tommy tried, but his German was a handful of classroom words and mispronounced apologies.

“Arm,” he said, touching his own forearm, then miming rolling up a sleeve. “Bitte.”

The woman’s eyes darted, uncertain. Slowly, she lifted her right arm and began to tug her sleeve upward. The fabric stuck. She pulled harder, and the dress seam strained at the shoulder.

Harris leaned in. “No—don’t tear it. Just—here.” He reached toward the sleeve.

The woman jolted back like he’d lunged with a knife.

“Nein!” she cried, voice suddenly loud. “Bitte! Nicht!”

Tommy’s heart hammered. Harris pulled his hands back, startled.

Marlowe cursed under his breath. “This is what I mean. Jumpy.”

The woman’s breathing turned shallow. Her eyes flicked from Harris to Tommy to the other soldiers. She looked like a trapped animal who had learned the world’s hands could do anything.

“Please don’t hurt me,” she said again, in English. The words cracked on the last syllable.

Tommy felt something shift inside him. Anger, but not at her. At the war, at the stories she’d lived, at the fear that had been poured into her like poison.

He crouched so his face was level with hers, careful not to invade her space.

“My name,” he said, tapping his chest, “Tommy. Thomas.”

He gestured toward Harris. “Doc. Help.”

He took off his helmet slowly, set it on the table, and held out his empty hands like proof.

The woman stared. Her shoulders loosened by a fraction.

“Your name?” Tommy asked gently.

Her lips trembled. “Liesel,” she whispered. “Liesel Bauer.”

Tommy nodded like he’d been given something sacred. “Liesel. Okay.”

Harris watched, eyebrow raised. “You gonna sweet-talk the rash away?”

Tommy ignored him. He looked at Liesel’s sleeve. The seam was tight, and the dress was clearly too small or shrunk from washing in bad water. Rolling it up would hurt, maybe tear anyway.

Harris reached for a pair of scissors, then stopped. “If she won’t let me touch it…”

Marlowe’s patience frayed. “We can’t skip checks. Not with typhus rumors.”

Tommy’s mind raced. He needed a way to see her arm without making her think she was being attacked. He needed clarity. He needed consent, even if the word wasn’t one the war had taught anyone properly.

He gestured to the scissors, then mimed cutting cloth—slow, careful. He looked at Liesel and shook his head, then mimed pain. He pointed at her shoulder seam, then at the dress front, indicating an opening that would avoid tugging the sleeve.

Liesel’s eyes widened with confusion, then fear.

Tommy quickly shook his head and spoke, slow.

“No… hurt,” he said. “No… bad. Only… look.” He mimed looking, then pointed to the medic’s red cross patch. “Help.”

Liesel stared at the red cross patch. Her eyes lingered there, as if searching her memory for what it meant.

Harris gently set the scissors on the table, far from her reach, so they looked less like a threat. Then he pulled out a strip of clean white cloth and held it up like a peace flag. He pointed to Liesel’s arm again.

Liesel swallowed hard. Her gaze flicked to the watching crowd. She seemed to realize that refusing might bring more fear later—more force. Her shoulders sagged slightly.

“Okay,” she whispered, barely audible. “Okay.”

But the word sounded like surrender, not agreement.

Tommy felt sick.

He had an idea then—clumsy, but maybe better.

He reached into his pocket and pulled out his own handkerchief, a blue one embroidered with a tiny wheat stalk. His mother had stitched it and mailed it after his first letter from England.

Tommy unfolded it and held it out to Liesel.

She looked at it, bewildered.

“Hold,” Tommy said, placing it gently in the air between them.

Liesel hesitated, then took it. Her fingers gripped it tightly, knuckles pale.

Tommy pointed to the table. He pantomimed placing the handkerchief over someone’s eyes, then shook his head and waved his hands in a frantic “no” to show that wasn’t what he meant. He took a breath, then mimed using cloth to cover, to protect.

He pointed to the front of her dress, the bodice, then to his own shirt buttons, miming opening without exposing. He was trying to say: we can create a barrier. We can make this less humiliating. We can make this safe.

Harris caught on. He took another cloth and held it up like a screen. “We can do privacy,” he muttered.

Marlowe’s expression softened. “Do it quick.”

Harris and Tommy positioned two canvas blankets between Liesel and the courtyard, creating a small privacy corner near the table. It wasn’t perfect, but it reduced the eyes.

Liesel watched the makeshift barrier go up. Her breathing eased slightly.

Tommy stood in front of her, not too close, and spoke as clearly as he could.

“I will… cut,” he said, pointing to the seam of her dress near the shoulder and neckline. “Small. Here.” He pinched the air to show a tiny cut. “Not… take. Not… shame. Only… arm.”

Liesel’s eyes glistened. “Why… cut?” she whispered.

Tommy struggled for words. He pointed to her scratching, then to Harris’s supplies, then mimed lice crawling on his own arm, making a face of disgust.

Liesel’s mouth tightened, understanding dawning. “Läuse,” she said. Lice.

Tommy nodded quickly. “Yes. Lice. Rash.”

Liesel shut her eyes for a moment, then opened them. She nodded once, like a soldier accepting an order.

“Okay,” she whispered again, and this time the word sounded a little less like defeat.

Harris picked up the scissors, holding them with two fingers, blade pointed away. He handed them—not to Liesel, but to Tommy, with a look that said, You’ve got her trust. Don’t break it.

Tommy’s hands trembled slightly as he took the scissors. He felt every eye outside the barrier even if he couldn’t see them.

He crouched. “Ready?” he asked softly, though he wasn’t sure she understood.

Liesel clutched the handkerchief and nodded. Her jaw was clenched, bracing.

Tommy made the smallest cut he could, just enough to loosen the seam. The fabric gave with a soft rip.

The sound was louder in the cramped privacy space than it had any right to be.

Liesel flinched hard.

“Please don’t hurt me,” she breathed, reflex.

Tommy’s chest tightened. “Not hurt,” he said quickly. “Not hurt.”

He carefully widened the opening, tearing only where the cut allowed, so the dress wouldn’t pull at her arm. He used another cloth to cover her chest area, preserving her modesty as best he could.

Then, gently, he moved the loosened fabric aside to reveal her right forearm.

The skin beneath was angry red, dotted with raw scratches. There were small clusters that looked like bites. And there was something else: beneath the rash, a series of dark purple bruises in the shape of fingers.

Tommy’s breath caught.

Harris leaned in, his expression changing instantly from routine to alert. He didn’t touch yet—he just looked.

“Those bruises,” Harris murmured. “Not from lice.”

Tommy felt heat rise behind his eyes. He wasn’t naive. He knew what war did to people. He’d heard rumors about camps, reprisals, men taking what they wanted because the world was breaking and consequences felt far away.

But seeing bruises shaped like hands on this thin woman’s arm made something in him go cold.

Liesel watched their faces, terrified again.

“What?” she whispered. “What wrong?”

Tommy swallowed hard and forced his voice to stay gentle.

“Rash,” he said, pointing to the bites. “We help.”

Harris nodded quickly, keeping his face calm. “Yeah. Rash. We treat it. We’ll also… make a note.”

He glanced at Tommy, and Tommy understood: We need to ask questions. Carefully.

Harris took out ointment and a small bowl of warm water. He dipped a cloth, wrung it out, and held it up so Liesel could see it.

“Okay?” he asked, slow.

Liesel’s eyes darted to Tommy.

Tommy nodded. “Okay. Help.”

Liesel nodded, trembling.

Harris cleaned the rash gently, then applied ointment in thin layers. Liesel winced but didn’t pull away. Tears slid down her cheeks silently.

When Harris finished, he wrapped her forearm with a clean bandage.

“Better,” he said, though the word was more for hope than certainty.

Tommy carefully adjusted the dress fabric back into place, using a safety pin from Harris’s kit to fasten it so she wouldn’t be left exposed or embarrassed. He tucked the torn edges neatly, as if he could undo the violence of that ripping sound by making it tidy.

When the dress was secured, he stepped back and set the scissors on the table.

Liesel looked down at the bandage, then up at Tommy. Her eyes were flooded, but her fear had shifted. It was still there—fear didn’t disappear in a day—but now it had something new mixed in: confusion, and a fragile, shaky relief.

“You… not hurt,” she whispered.

Tommy shook his head. “No.”

Liesel swallowed. “I… thought…”

Tommy didn’t ask what she thought. He could guess. He didn’t want to make her say it out loud.

Harris cleared his throat. “Liesel,” he said, trying her name like it might help, “who did this?” He pointed gently to the finger-shaped bruises.

Liesel stiffened, eyes flicking away.

Tommy’s stomach sank. “It’s okay,” he said softly. “You safe.”

Liesel’s lips trembled. She shook her head. “No safe,” she whispered. “Not always safe.”

Tommy felt anger flare, sharp and hot. Not at her. At the idea that even after surrender, even after the big speeches about liberation, a woman could still be unsafe because someone decided she was powerless.

Marlowe’s voice came from outside the barrier. “How much longer?”

Harris called back, “Two minutes.”

Then he leaned toward Tommy and spoke quietly. “We need to get her into the women’s section by the church. They’ve got a matron. Safer. Less mixing.”

Tommy nodded. “I can escort.”

Harris looked at him. “You steady enough?”

Tommy thought of the bruises. He thought of his mother’s handkerchief still clenched in Liesel’s fist like a lifeline.

“I’m steady,” he said, though his insides felt like broken glass.

When they lowered the blankets and stepped back into the courtyard, the watching eyes shifted like a flock of birds. Some looked away quickly, embarrassed. Some stared. Some looked resentful, as if kindness was an insult.

Tommy kept his posture calm. He offered Liesel the handkerchief again.

“That’s yours,” he said.

Liesel blinked. “No… yours.”

Tommy shook his head. “Keep.” He tapped the wheat embroidery. “Home.”

Liesel stared at the stitched stalk, then folded the cloth carefully and tucked it into her dress pocket like it was a passport.

Marlowe approached, eyes flicking to the bandage and the pinned dress. He understood enough to soften his tone.

“Good,” he said. “Reed, take her to the church station. Then report back.”

Tommy nodded. He gestured for Liesel to walk with him.

They moved through the yard, passing groups of civilians. Some murmured. A few women watched Liesel with something like sympathy. One older woman reached out and touched Liesel’s elbow gently as she passed, a silent reassurance.

Liesel kept her head down, but she walked.

The church was half standing, half broken. One stained-glass window had survived, a patch of color in a world of gray. Inside, cots were lined up. A German-speaking nurse—an older woman in a plain dress with sleeves rolled up—moved between patients with brisk competence.

When she saw Tommy and Liesel, she stepped forward.

“Was ist los?” she asked sharply.

Tommy turned to her, helpless. Then Sato—an interpreter attached to their unit—appeared from behind a curtain, as if summoned by the need.

Sato’s eyes took in Liesel’s bandage, the pinned dress, the handkerchief in her pocket. His expression tightened.

“She’s been treated for a rash,” Sato said in English, then in German to the nurse. “Und… es gibt Verletzungen. Sie braucht einen sicheren Platz.”

The nurse’s face hardened with protective anger. She motioned Liesel toward a cot behind a partition.

Liesel hesitated, looking back at Tommy.

Tommy felt his chest tighten. He wasn’t sure what he meant to her—authority, threat, help, all tangled together.

“It’s okay,” he said softly. “Safe.”

Liesel nodded once and followed the nurse.

Sato lingered beside Tommy. “You did good,” he said quietly.

Tommy’s voice came out rough. “I tore her dress.”

Sato nodded, understanding the weight of it. “You tore cloth so she could be treated. That matters.”

Tommy stared at the broken altar. “She thought I was going to—”

“Don’t finish that sentence,” Sato said gently. “Just remember what it means: fear has a memory.”

Tommy swallowed. “What do we do about the bruises?”

Sato’s jaw tightened. “We report. We document. We put her where she’s protected. And if the bruises came from someone in uniform…” He didn’t finish either, but his eyes said enough.

Tommy returned to the courtyard, but the day stuck to him like smoke. He tried to focus on tasks—rolling up sleeves, handing out soap, directing lines—but his mind kept replaying Liesel’s flinch at the sound of cloth tearing.

That evening, after the last distribution was done and the camp settled into uneasy quiet, Tommy sat on the schoolhouse steps with his mess tin untouched. The sky was bruised purple at the horizon, the kind of sunset that looked almost too pretty for a place like this.

Marlowe sat beside him, lighting a cigarette. He offered one to Tommy. Tommy shook his head.

Marlowe exhaled a thin stream of smoke. “You look like you swallowed a stone, Reed.”

Tommy stared at his hands. “She begged me not to hurt her.”

Marlowe’s face darkened. “Yeah.”

Tommy looked up sharply. “Yeah what? You knew this happens?”

Marlowe’s voice was quiet, tired. “I know war makes men think they can take whatever they want. I also know good men spend the rest of their lives trying to clean up what bad men do.”

Tommy swallowed hard. “How do you clean it up?”

Marlowe stared out at the courtyard. “You do what you did. You slow down. You make a barrier. You treat a rash and pin a dress and prove with your hands that your hands aren’t like the ones that hurt her.”

Tommy’s throat tightened. “It doesn’t feel like enough.”

Marlowe flicked ash away. “It’s not enough. But it’s something. And in a place where so much has been taken, something matters.”

The next morning, Tommy went to the church station before his shift. He didn’t have official business there. He just… needed to know.

Sato was there, translating for the nurse. When he saw Tommy, he nodded toward the partition.

“She’s awake,” Sato said. “She asked about you.”

Tommy’s heart jolted. “She did?”

Sato’s expression was soft. “She asked if ‘the young soldier with the wheat cloth’ was real.”

Tommy swallowed. “Can I… talk to her?”

Sato considered, then nodded. “Keep it simple. Keep it respectful.”

Tommy stepped behind the partition. Liesel sat on a cot with a blanket around her shoulders. Her face looked less rigid today, though her eyes were still cautious.

When she saw Tommy, she tensed, then relaxed slightly, as if remembering his hands.

“You,” she said quietly.

Tommy nodded. “Me. Tommy.”

Liesel touched the pocket where the handkerchief was tucked. “Cloth… from your mother?”

Tommy blinked. “Yes.”

Liesel looked down. “It is… small thing. But…” She struggled for English. “It makes… not monster.”

Tommy’s chest tightened. “I’m sorry,” he said, though he wasn’t sure what part he meant. All of it, maybe.

Liesel’s eyes shimmered. “I am sorry too,” she whispered.

Tommy frowned. “For what?”

Liesel’s mouth trembled. “For fear. For… thinking you hurt.”

Tommy shook his head firmly. “No. Fear… makes sense.”

Liesel stared at him for a long moment. “In the last months,” she said slowly, “many men… different uniforms… same hands.”

Tommy felt his stomach twist. “I’m sorry,” he repeated, and this time the words felt like they had weight.

Liesel swallowed, blinking back tears. “When you cut… I thought…” She stopped, choking on the memory.

Tommy’s voice was gentle. “I know.”

Silence filled the partition, thick with things they couldn’t say.

Then Liesel surprised him. “You made wall,” she said, gesturing toward where the blankets had been. “So people not watch.”

Tommy nodded. “Yes.”

Liesel looked at him, eyes steady now. “That… is respect.”

Tommy swallowed hard. “It should be normal.”

Liesel’s mouth tightened in a sad smile. “In war, normal dies first.”

Tommy didn’t know what to say. So he did what his mother had taught him when he didn’t know what to say: he offered something practical.

“You need anything?” he asked.

Liesel hesitated, then spoke quietly. “Paper. Pencil.”

Tommy blinked. “To write?”

Liesel nodded. “If I am sent… somewhere. I want… name. For nurse. For you. For… record.”

Tommy realized she wanted proof. Proof of kindness. Proof that not all hands were the same.

“I’ll get it,” he said quickly. “I’ll bring.”

He hurried back to the schoolhouse office and found a stub of pencil, some paper forms with blank backs, and a small envelope. He returned and handed them to Liesel.

She took them carefully, as if afraid they’d dissolve.

She wrote her name in careful letters: Liesel Bauer. Then, beneath, she wrote the only English she seemed to trust:

He did not hurt me. He helped me.

Her hand shook, but the words were clear.

She held the paper up to Tommy, eyes searching his face for a reaction.

Tommy felt something break open in his chest—not pride, but grief and relief mixed together.

“Thank you,” he said softly.

Liesel nodded once. “If someone asks… I show.”

Tommy swallowed. “If anyone hurts you here… you tell the nurse. You tell Sato. You tell—” He stumbled, realizing he didn’t know how much protection he could promise.

Liesel’s gaze softened. “You cannot fix all,” she said quietly. “But you fixed one moment.”

Tommy stood there for a long time after, feeling the truth of it settle into him like a stone that finally found the bottom of the river.

Weeks passed. The holding site thinned as people were processed—sent to relatives, to work brigades, to refugee centers. Tommy’s unit received orders to move, then wait, then move again. Postwar Europe was a puzzle the size of a continent.

On Tommy’s last day at the schoolhouse camp, he went to the church station to say goodbye.

Liesel wasn’t there.

The nurse told Sato she’d been transferred to a women’s shelter near Frankfurt, under the care of a relief organization.

Tommy felt disappointment, then relief. Shelter sounded safer than a holding yard.

As he turned to leave, the nurse handed Sato a folded note. Sato opened it, read quickly, then passed it to Tommy.

It was the paper Liesel had written, but with an added line in careful English:

Tell your mother: the wheat cloth made me brave again.

Tommy’s eyes stung so sharply he had to blink hard. He folded the note carefully and tucked it into his breast pocket, right over his heart.

On the ship home months later, Tommy stood on the deck at night, watching the Atlantic roll beneath the moon. The ocean looked calm in the dark, but he knew better. Calm was often just a disguise.

He took out the note and read it again, fingers tracing the letters.

He thought about what he would tell his mother. How would he explain that her stitched handkerchief had crossed an ocean and become a small shield for a stranger? How would he explain that the loudest sound he remembered from the war wasn’t a gunshot, but the soft rip of cloth and the fear that came with it?

When he finally made it home, his mother met him on the porch, wiping her hands on her apron the way she always did. His father stood behind her, hat in hand, eyes shining.

Tommy hugged them, and for a moment he was just a son again, not a soldier.

At the kitchen table that evening, his mother brought out bread still warm from the oven. His little brother talked too fast about school. The radio played low in the corner like the world had never been on fire.

His mother watched Tommy carefully, the way mothers do when they know there are things their sons won’t say.

After dinner, when the dishes were done and the house settled, Tommy reached into his pocket and pulled out the note. He slid it across the table toward his mother.

His mother read it once, then again. Her eyes filled, and she pressed a hand to her mouth.

“Oh, Tommy,” she whispered.

Tommy stared at the grain in the wooden table. “She thought I was going to hurt her,” he said quietly. “She begged me not to.”

His mother’s face tightened, grief and anger flickering across it. “And you didn’t.”

“No,” Tommy said, voice thick. “But I understood why she thought it.”

His mother reached across the table and took his hand. Her fingers were warm, familiar, steady.

“You can’t control what the world did to her,” she said softly. “But you controlled what you did in that moment.”

Tommy swallowed hard. “I tore her dress to treat her arm. I pinned it back. I tried to make a barrier so people wouldn’t stare.”

His mother squeezed his hand. “That’s called dignity,” she said, voice firm. “And sometimes dignity is the only medicine people get.”

Tommy’s eyes burned. “It didn’t feel like enough.”

His mother’s gaze was steady. “If she wrote that you made her brave again,” she said, tapping the note, “then it was enough for that day.”

Tommy nodded slowly, letting the words settle.

Outside, crickets sang. The world felt unbearably ordinary, and Tommy realized that was the greatest gift.

He went to bed that night with the note under his pillow like a talisman.

Years later, when people asked him about the war, they expected stories about battles and heroes. They expected him to talk about guns and flags and victory.

Sometimes he did, because those were the stories people could handle.

But the story that stayed closest to his heart was about a woman named Liesel Bauer, a schoolhouse courtyard, a desperate plea, and a moment when a ripping sound meant not harm—but help.

It was the story that taught him a truth he carried into every ordinary day afterward:

War can teach the world to fear hands.

Peace begins when someone uses their hands to prove the fear isn’t always right.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.