“Please Don’t Hurt Me” – German Woman POW Shocked When American Soldier Tears Her Dress Open. NU

“Please Don’t Hurt Me” – German Woman POW Shocked When American Soldier Tears Her Dress Open

April 30, 1945—those last days of the war felt thin and brittle, like the world itself had been stretched too far and could snap at any moment. The air was cold that morning near Leipzig, and it carried the smells of a collapsing country: damp earth churned by boots and tires, engine oil, wet ash from burned fields, and the faint bitterness of smoke that never seemed to leave the horizon. Somewhere beyond the low hills and broken farm roads, the front lines were moving so quickly that yesterday’s “safe” place could become today’s battlefield without warning.

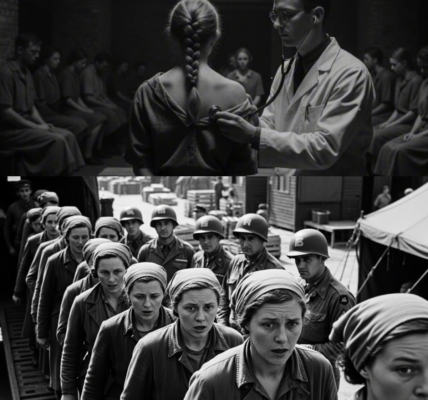

In a crowded holding yard—nothing more than a fenced collection point thrown together in haste—German women stood in silence, waiting to learn what their fate would be. Some were auxiliaries, some clerks, some nurses’ aides. Not frontline fighters. Not the kind of people who had carried rifles into trenches. But defeat did not sort fear by job title. Defeat had a way of flattening everyone into the same posture: shoulders tight, hands close, eyes lowered, breath shallow.

They expected anger.

They expected punishment.

Some expected revenge.

For years, they had been told that the Americans would do terrible things to captured German women—things unspeakable, things that made surrender feel like a different kind of death. Posters, radio broadcasts, speeches—an endless chorus—had drilled the warning into them until it became muscle memory: capture means disgrace. Foreign troops have no mercy. Better to die than fall into enemy hands.

One woman, twenty-four-year-old Elise Weber, stood among them with her gaze fixed on the ground, as if lifting her head might shame her family. She wasn’t crying. She wasn’t praying out loud. She had passed beyond panic into something quieter and more dangerous: a rigid, internal readiness for whatever humiliation the world had promised her. Fear had shaped her for so long that it now felt less like emotion and more like identity.

A few hours earlier, Elise and the others had stepped out from behind a ruined barn with their hands raised, emerging cautiously like animals that had learned that any sudden movement could be fatal. The barn was half collapsed, blackened where something had burned weeks ago. Behind it lay the evidence of retreat—discarded crates, broken wheels, scraps of fabric, and the kind of scattered belongings that told the story of an army dissolving into a thousand desperate individuals.

They walked slowly toward an American checkpoint. The air smelled of mud and engine oil and burned hay. A jeep idled beside the road, rattling like loose metal in a bucket. Several American soldiers watched them with uncertain eyes.

None raised a rifle.

None smiled either.

And somehow that neutrality—neither cruelty nor warmth—felt almost worse than violence would have. Because neutrality left room for imagination, and Elise’s imagination had been fed for years by propaganda designed to keep her terrified.

Her hands shook so badly that the small wooden medical case she carried tapped against her knee with each step. It was a simple box, the kind you might find in a clinic: rectangular, worn at the corners, with a latch that no longer fit perfectly. She carried it the way you carry something you’ve been ordered to protect: tight, close, instinctively, as if letting it slip could bring a bullet into your back.

She didn’t even know what was inside.

That was the strangest part.

The box had been handed to her during the retreat from the east. A wounded officer—face gray, voice sharp despite pain—had pressed it into her arms and said: “Protect this. Do not let it fall into enemy hands.” In those last collapsing weeks, orders felt like anchors. You clung to them because everything else was sliding away. Elise did not question him. She did not open the box. She simply obeyed. Obedience, by then, was not ideology. It was survival.

At the checkpoint, the American officer—a lieutenant who looked barely older than Elise—spoke in a calm voice. The women couldn’t understand the words, but the tone surprised them. No shouting. No insults. No spitting. He pointed toward a patch of gravel and motioned for them to wait there. A sergeant wrote numbers on a clipboard. Everything moved with a kind of controlled routine, almost administrative, as if surrender was paperwork.

Elise expected rough handling, at minimum. At worst… she tried not to name the worst.

Instead, a soldier passed out tin cups of water.

Another brought blankets from a supply truck.

When one older woman collapsed from exhaustion, two Americans rushed forward—but the Germans recoiled, instinctively stepping back, convinced that the help was a trick and the grabbing hands would turn violent.

The soldiers didn’t shout. They didn’t laugh.

They simply lifted the older woman carefully under her arms and set her gently against a tree trunk so she wouldn’t fall into the mud.

Elise felt confused in a way that made her stomach tighten. Fear had shaped her life so completely that kindness looked dangerous. Kindness felt like bait.

She remembered a neighbor in Munich whispering, “They’ll starve you first, then decide what to do with you.” She remembered a former Hitler Youth instructor who had once told her class, “Better to die than fall into enemy hands.”

And yet, the camp kitchen nearby was boiling potatoes in a large metal pot. Steam drifted into the air like warm white clouds. Elise smelled pepper, broth—real food, not the dry crusts rationed in collapsing cities. Her body reacted immediately. Hunger rose like an animal. Still she refused. She held her wooden box tighter, as if hunger itself were a weakness the Americans could exploit.

A private standing nearby noticed Elise’s trembling. He spoke softly, his voice gentle in a way that didn’t match the image Elise had been taught to expect.

“Ma’am, you okay?”

Elise stepped back quickly, nearly losing her balance. The private raised both palms—universal gesture: I’m not a threat. His expression was puzzled, almost hurt, as if he couldn’t understand why she looked at him the way someone looks at a predator.

Later, he would write a brief note to his unit, a sentence that captured the strange paradox of those last days: They looked more scared of us than we were of them.

As the sun dipped lower, the women were moved into a wooden holding shed and then back into the yard—processing, counting, waiting. Elise sat near the fence with the box on her lap. By then, something else had begun to trouble her: the box felt warm.

Not warm like it had been in her hands all day.

Warm like it was alive.

She told herself it was only her imagination, that fear could make you feel things that weren’t real. But when she shifted the box against her ribs, a faint chemical smell leaked from the cracks—sharp like metal and vinegar. It made her nose sting. It reminded her of hospital rooms, of disinfectant so strong it seemed to strip the air itself.

Elise’s first thought was not “danger.” It was “guilt.”

Because guilt, too, had been trained into her.

She wondered if she had broken something. If she had failed the officer’s order. If the Americans would accuse her of sabotage. If they would punish her for carrying something suspicious.

She looked around the yard—American soldiers walking with their quiet routine, checking lists, sharpening pencils, carrying crates. Their voices rose and fell like office chatter rather than the roar of conquerors. Discipline was everywhere. It was not the disorder of men given permission to do anything they wanted. It was order—rules—structure.

That should have been reassuring.

But Elise had lived too long inside a story that told her order could also be cruel.

Morning came again with soft gray light. Dew clung to fence wires. The ground smelled of wet ashes. Elise sat with her back against a wooden post, knees pulled close, the box beside her like a coiled threat. She had slept little. Every snap of a branch, every engine cough, every bootstep made her flinch.

Still, nothing matched the warnings.

A sergeant opened a container of rations. Inside were items Elise had not seen in months—corned beef, canned fruit, chocolate, bread that did not crumble into dust. A cook ladled soup into tin cups. Steam drifted toward the women carrying the warm smell of carrots and salt. Some whispered, “This is a trick.” Others whispered, “They want us to trust them, then they’ll strike.”

Even when hunger twisted inside them, many refused the food because propaganda had taught them that accepting anything from an enemy was surrendering more than your body—it was surrendering your dignity.

A private approached with paper tags for identification. When he reached Elise, he knelt so he wouldn’t tower over her.

“Ma’am, name?”

Elise hesitated, then answered softly: “Elise.”

He repeated it carefully, trying to spell it right, then placed a cup of water beside her and walked away when she refused to take it. He didn’t force kindness on her. He offered it and let it be.

That gentleness confused her more than violence would have. Violence would have confirmed her story. Gentleness threatened to erase it.

By midday, the yard slipped into a quiet rhythm. Prisoners sat in rows. Soldiers wrote reports. The smell of boiled potatoes hung in the air. Elise’s stomach tightened at the scent, but she did not reach out.

Because the box was warmer now.

And the faint chemical smell had grown sharper.

When Elise shifted her weight, the box brushed her dress, leaving a darker stain on the fabric near her right side. She looked down, uneasy. The warmth seemed stronger, almost pulsing. She pressed her hand against the lid and jerked it away instantly—the wood felt hot.

She didn’t know what that meant. She only knew it felt wrong.

As the afternoon stretched into evening, the sky above the holding yard turned dull orange, the color of dust in fading light. Elise sat near the fence with the box on her lap, breathing carefully, trying not to panic. But the heat seeped through the wood and into her body, and the smell made her eyes water.

A couple of soldiers walking nearby slowed, sniffing the air. One frowned.

“Smells like solvent,” he murmured to the sergeant beside him.

They scanned the yard casually, not alarmed yet—just noticing. Elise lowered her gaze. She didn’t want attention. Attention meant questions. Questions meant risk.

Inside the box, a glass vial had cracked during the retreat—likely after an artillery shock, the kind that rattled bones. In wartime medical kits, concentrated sterilizing agents were common: designed to disinfect quickly, harsh enough to burn if mishandled. Elise didn’t know any of this. She had not opened the box. She had been too afraid to look.

Now the chemical began to leak more steadily.

A soft hiss escaped from the box, so quiet that at first Elise thought it was her imagination. Then the smell intensified, stinging her nose like a warning. She set the box down quickly. The warmth still clung to her dress. The fabric on her right side had darkened and was sticking to her skin as if glued there.

She pressed her fingers against it—then winced sharply.

Pain.

Not a bruise pain.

A burning pain.

Elise’s breath caught. Panic surged, but it was a different panic now—less about Americans, more about the sudden realization that something she carried was hurting her, and she didn’t know how to stop it. She tried to peel the cloth away from her skin.

It didn’t move.

The fabric had fused to her side.

She pulled harder and gasped. Pain flared hotter. Her eyes filled with tears.

Across the yard, a corporal noticed her struggling and nudged the soldier beside him. They watched as Elise tried to stand and failed, her hand pressed to her ribs. The chemical smell reached them, sharper now.

A medic walking nearby caught it too. His expression changed instantly from routine calm to alarm. Medics learn certain smells the way firefighters learn smoke. He turned sharply, scanning until he saw Elise hunched over, dress stained, posture tight with pain.

He moved quickly toward her, raising a hand to catch the attention of a passing soldier.

“Ma’am—don’t touch that,” he said, voice urgent.

Elise didn’t understand the words. She understood the urgency. And the urgency—combined with her fear—made her do the wrong thing.

She clutched the dress tighter, as if hiding the stain would protect her. As if concealment could prevent punishment.

The medic stepped closer. Elise backed away. Her legs shook.

The box toppled from where she’d set it down and fell onto the gravel with a dull crack.

That crack was the moment everything changed.

The lid split. A fresh wave of chemical odor surged into the air—sharp, burning, metallic. Several soldiers turned at once. A few stepped backward, suddenly wary.

Elise stared at the spill like it was a snake.

The medic shouted, voice cutting through the yard: “Get her away from it!”

He wasn’t shouting at Elise. He was shouting for speed. For action. For the kind of immediate response that medical emergencies demand.

But Elise didn’t know that.

All she knew was that an American man was shouting and pointing and rushing toward her, and her mind—trained by years of fear—translated it instantly into the story she had always believed:

This is it. This is the moment.

Elise tried to push herself away from the spill, but the pain on her ribs pulled her back down. She grabbed the hem of her dress again, trying to rip it free.

It wouldn’t come.

The chemical had glued it to her skin.

A young American soldier—Private Leonard Carter—ran toward her. He had been quiet all day, the kind of man who looked more like a schoolteacher than a fighter. His boots kicked gravel as he slid to a stop.

He saw Elise’s terrified expression. He saw the spreading stain. He smelled the chemical.

He spoke softly at first, palms open.

“Ma’am, don’t touch it. Please—don’t—”

Elise flinched and raised her arms as if to protect herself. She backed away, eyes wide, breath fast and shallow.

The medic’s voice snapped again, sharper now: “Carter, you have seconds. I’ll get the cloth off her!”

That sentence—more than anything—showed the truth: they were not thinking about punishment. They were thinking about injury. About time. About preventing damage.

Carter didn’t hesitate after that. Training overrode everything. He reached forward quickly and grabbed the fabric near Elise’s ribs.

Elise screamed.

The scream tore through the yard like a siren. The German women froze. Some cried out. The fear they had carried for years surged all at once into a single sound. A few women turned their faces away as if they couldn’t bear to watch what they were certain was about to happen.

Elise’s mind collapsed into pure terror. She twisted, trying to pull away.

“Please don’t hurt me,” she sobbed in German.

Carter didn’t understand the words. He understood the terror. But he could also see the chemical spreading, eating through cloth, threatening skin beneath.

He pulled hard.

The sound was raw and unmistakable: fabric tearing, seam ripping straight down the side. A harsh ripping crack that made the entire yard flinch.

Elise cried out again and fell to her knees, shaking. For a fraction of a second, the world seemed to freeze: Germans horrified, Americans startled, the medic focused like a surgeon.

Then the medic was there, pouring water from a canteen in steady streams over the exposed area. The liquid hit the wound and the soaked fabric on the ground. The sharp chemical smell began to fade under the flood of water.

Elise stared, stunned. She expected laughter. She expected cruelty. She expected hands holding her down.

Instead she saw urgency—and something like fear in Carter’s eyes, not of her, but for her.

Carter crouched immediately, careful not to touch her skin where it was burning. His voice trembled as he spoke, as if he needed her to understand even if she couldn’t.

“It’s burning you. I’m not hurting you. It’s the chemical.”

Elise didn’t understand the words. But she saw his face. Not triumphant. Not mocking. Not cruel.

Terrified—because he knew how easily this could have gone wrong.

He tore away the last strip of cloth that was stuck to her side, peeling it off with a wince as if he could feel the pain through his own hands. Underneath, the skin was red, blistering in patches, angry and raw.

The medic continued rinsing. He shouted for supplies—bandages, ointment, whatever they had. A corporal lowered his rifle that he’d raised reflexively, the adrenaline draining.

A moment of heavy silence followed. Then voices returned in confused fragments: German women whispering, American soldiers shouting instructions, someone moving prisoners back to give space.

Carter stripped off his uniform jacket and placed it gently over Elise’s shoulders, careful not to press it against the burned area. He didn’t drape it with dominance. He draped it with a kind of awkward respect, as if he understood that even in an emergency, dignity mattered.

Elise clutched the jacket, trembling. She looked up at him with wide, disbelieving eyes.

For the first time, the story she had lived inside began to crack.

The medic guided Elise toward the field tent. Carter stayed behind for a moment, breathing hard, hands shaking. He watched as Elise was led away, still wrapped in his jacket, her fear slowly turning into bewilderment.

The yard returned to its routine, but the rip of fabric still hung in the air like an echo. Everyone had heard it. Everyone had interpreted it through their own history. In one instant, propaganda and reality had collided so violently that for a moment neither side knew what to believe.

Inside the medical tent, the air was warmer, filled with lantern light and the smell of canvas and disinfectant. Elise sat on a cot, Carter’s jacket wrapped around her like armor. Her breathing steadied, though every inhale reminded her of the burn.

The medic—Sergeant Hill—worked calmly. He had treated countless injuries, but this one carried a different weight because it wasn’t just a wound. It was a misunderstanding powerful enough to ignite chaos.

He rinsed the burn again. He cut away remaining threads with a small tool. Elise flinched, then relaxed when she realized each movement was careful.

A German interpreter arrived, someone who had lived long enough between worlds to build a bridge with words. He translated slowly, choosing simple phrases.

Elise asked the same question twice, voice shaking: Why did he tear it? Why did he do that?

The interpreter explained: The cloth was burning you. He had to act fast. If it stayed, it would have scarred you worse.

Elise stared at her bandaged side, the logic settling into place like a stone finally dropping. She nodded, still overwhelmed, but no longer drowning in fear.

Carter stood near the tent entrance, posture stiff. He kept replaying the scream, the ripping sound, the horrified faces. He hadn’t meant to terrify her. He had seen danger and acted. But he also knew how it looked in the eyes of someone taught to fear him.

The interpreter walked over and told Carter: She wants to know if you were angry with her.

Carter shook his head so quickly it was almost painful. “No. Not for a second. Tell her I was trying to help. That’s all.”

When the interpreter repeated it, Elise looked up at Carter. Something shifted in her face—tiny, fragile. The fear didn’t vanish all at once; fear rarely does. But it loosened, just enough for another emotion to enter.

Relief.

“El… danke,” she said softly.

Thank you.

The words were quiet but clear. They moved through the tent like a thread sewing something torn.

Sergeant Hill finished wrapping her side with clean gauze. The bandage smelled faintly of medical linen and vinegar. Elise held the jacket tighter around her shoulders.

When she returned to the yard, evening light softened the gravel into something almost gentle. The other women watched her closely, searching her face for proof that their fears were justified.

Some looked relieved when they saw Elise alive, walking, covered properly, not dragged.

Others looked confused.

Elise pressed her hand lightly against the bandage. It hurt, but the hurt was now understandable. It had a cause. It had treatment. It had an end.

And in that clarity, Elise felt something more unsettling than pain:

She felt doubt—about everything she had been taught.

The Americans in the yard continued their routine: distributing food, issuing identification tags, helping those who collapsed, maintaining order. It wasn’t perfect. It was still captivity. It was still defeat. But it wasn’t the nightmare propaganda had promised.

Elise watched Carter from a distance. He avoided staring at her, as if he didn’t want to make her feel hunted. But when their eyes met, he gave a small nod—simple, respectful.

This time Elise returned it without hesitation.

She thought about the moment the dress tore. How it had sounded like violence. How it had felt like humiliation. How she had believed, in that second, that her life was ending in disgrace.

And then how it had turned into something else entirely: a rescue done so urgently it looked like cruelty—until you understood the truth.

That was the cruelest trick propaganda had played on her: it had stolen her ability to recognize help.

In the days after, the story of the torn dress spread quietly through the holding yard. Not as gossip, but as evidence. Women repeated it in hushed voices, each retelling slightly different because fear always edits memory. Some said, “He attacked her.” Others corrected, “No—he saved her.” The debate itself was proof of transformation: they were no longer repeating slogans. They were arguing with reality, trying to reconcile it.

Elise eventually gave a short statement for medical records, translated by the interpreter. Her words were simple: I thought the soldier meant harm. Instead, he saved me.

That sentence didn’t erase years of war. It didn’t fix what had been done. But it was a crack in the wall—a small opening where truth could enter.

For Carter, the incident stayed with him too. He wrote later that he had never felt more aware of how thin the line could be between rescue and terror, between doing the right thing and being seen as a monster. He understood that Elise’s fear wasn’t personal. It was inherited, manufactured, rehearsed.

And yet it had been real enough to make her scream.

That’s the part people often forget about propaganda: it doesn’t just lie to your mind. It rewires your reflexes. It teaches your body what to fear.

On that cold morning near Leipzig, when an American soldier tore a German woman’s dress open, it looked—at first glance—like exactly what the terrified rumors had always warned about.

But what really happened in that moment was the opposite.

It was a soldier seeing a medical emergency and acting so fast that he accidentally collided head-on with years of terror. It was a woman learning, in the most shocking way possible, that the enemy she had been taught to dread could still choose restraint, discipline, and humanity.

And in the long shadow of World War II, that reversal mattered.

Not because it was sentimental.

Because it was true.

Because it revealed something the war had tried to bury: even after years of hate, even after collapse, even at the bitter end—one act of urgent compassion could flip an entire story on its head.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.