Patton’s Apache Battalion: The Men the US Was Afraid to Unleash in WWII

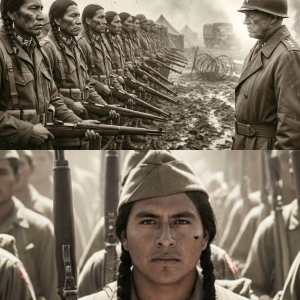

To the arrogance of the German high command, the men of the 45th division were nothing to fear. Nazi propaganda dismissed them as racially inferior. They called them savages from the American West, undisiplined and primitive. But General George S. Patton, watching the invasion of Sicily through his binoculars on that July morning in 1943, saw something very different.

Where the Germans saw inferiority, Patton saw the ultimate weapon. He saw a lethal focus that no drill sergeant could teach. While regular army units were bogging down in the heavy surf of Skoiti, terrified by the mortar fire and the screaming chaos of the beach, the men of the 180th regiment were already moving. They were the Thunderbirds.

Thousands of them were Native Americans, Apaches, Cherokees, Chaktos, and Navajos, men who had been treated as secondclass citizens back home. But here on the burning sands of the Mediterranean, they were proving to be the most valiant soldiers on the field. Patton watched as they ignored the confusion that paralyzed other units.

He saw them slip out of the landing craft, not as a herd of panicked drafties, but as a coordinated pack. They didn’t wait for orders. They didn’t wait for the officers to read maps. They looked at the dry, rocky hills of Sicily, terrain that looked just like the badlands of New Mexico, and they knew exactly what to do.

While the superior German troops sat in their concrete bunkers waiting for a frontal assault, the Thunderbirds were already flanking them. They moved with a silence that unnerved the enemy. They communicated with hand signals and bird calls, cutting through the noise of battle. By the time the German machine gunners realized they were being hunted, the knife was already at their throat.

The US Army had been afraid to unleash these men. The top brass in Washington worried they were too wild, too independent to fit into a modern military. They wanted soldiers who marched in step. But Patton didn’t want a parade. He wanted a breakthrough. He looked at the red and yellow Thunderbird patch on their shoulders and smiled.

He knew that while the enemy was fighting for a dictator, these men were fighting for something much deeper. Their land, their brothers, and their warrior heritage. The Germans had underestimated them. The American government had marginalized them. But on day one of the invasion, the Apache battalion was teaching the world a lesson in power.

They had taken the beach. Now they were coming for the island. But before we continue this journey, tell me where you’re watching us from. And may God bless you wherever you are. Now let’s go deeper. To understand why these men fought differently, you have to look at where they came from. Most of the soldiers in the 180th Infantry didn’t grow up on paved streets.

They came from the Chilaco Indian Agricultural School in Oklahoma, a place built by the government to assimilate them. For years, they were told to forget their languages. They were told to forget their traditions. But you cannot erase a heritage that runs in the blood. In the barracks of the 45th Division, you heard a mix of languages that would baffle a German intelligence officer.

Creek, Cherokee, Chakaw, Chickasaw, and Seol. But to the rest of the army, and certainly to the enemy, they were simply the Indians. And among them, the spirit of the Apache warriors loomed large. A reputation for endurance that seemed superhuman. There was a bitter irony here. These men were training to defend a constitution that didn’t fully recognize them.

Back home, they couldn’t even vote in some of the very states they were drafted from. Yet when the call came, they didn’t hesitate. They formed a brotherhood that was tighter than any standard platoon. They called each other brother, and they meant it. While other units struggled with the heat and the rough living conditions of the front lines, the men of the 180th shrugged it off.

They were used to hard land. They were used to scarcity. They took the skills their grandfathers had used to survive on the shrinking frontiers, tracking, silence, observation, and they militarized them. The US Army had unwittingly created an elite force. They took men who had been raised to survive against all odds, gave them uniforms, and pointed them at the greatest evil the world had ever seen.

The weapon was loaded. It was time to pull the trigger. General Patton was not a patient man. By mid July, the invasion was slowing down. The roads were clogged with rubble and the German resistance was stiffening. Patton, known as Old Blood and Guts, was pacing in his command tent.

Furious at the delay, he needed to capture the Biscari airfield, a critical prize that would allow Allied planes to dominate the skies. But the airfield was a fortress guarded by elite German paratroopers who had dug in deep. Regular infantry attacks were getting chewed up. Patton needed a sledgehammer, but he didn’t have one, so he reached for a knife. He ordered the 45thdivision forward.

This was the moment the legend of the Apache Battalion truly began to take shape in the whisper networks of the war. It wasn’t an official name. You won’t find Apache Battalion on the morning reports, but it was the spirit of the tactic. The commanders knew that if they sent these men in a straight line, they would die like anyone else.

But if they let them fight their way, that was a different story. The officers of the 180th looked at the map. They looked at the heavily defended roads leading to the airfield. And then they looked at the rough, broken terrain that the Germans had left unguarded because they thought it was impassible. The order went down the line. Drop the heavy packs.

Fix bayonets. We are going off road. Patton watched the reports coming in. He saw the speed at which they were moving. It defied the logic of modern warfare. They weren’t waiting for the tanks. They were outpacing them. The general realized that these men weren’t just following orders.

They were competing with each other to be the first to the fight. He demanded the impossible. Take the airfield before the enemy could destroy the runway. And the men of the 45th simply tightened their bootlaces and stepped into the breach. Nighttime in Sicily is pitch black. The ancient stone villages shut out the light and the olive groves turn into mazes of shadow.

For the average American soldier in 1943, the night was terrifying. You couldn’t see the enemy. You couldn’t use your superior air power. The doctrine was to dig in and wait for dawn. But the Germans quickly learned that the night belonged to the Thunderbirds. As the 180th closed in on the airfield, they didn’t stop when the sun went down.

This was their time. Drawing on skills passed down through generations of hunters, they navigated without compasses, reading the stars and the silhouette of the hills. They moved in a way that regular troops couldn’t replicate. They didn’t clank their cantens. They didn’t step on dry branches. One German sentry after another was neutralized before he could even reach for his alarm flare.

It was psychological warfare as much as physical. Imagine being a German soldier, confident in your position, only to find that your perimeter has been breached without a single shot being fired. The panic that spread through the German lines was palpable. They started firing blindly into the dark, wasting ammunition on shadows.

But the Apache element of the 45th wasn’t shooting back. Not yet. They were closing the distance. They were getting inside the enemy’s guard. They crawled through irrigation ditches and climbed over stone walls, getting so close they could smell the cigarette smoke of the enemy. They were setting the stage for an ambush from within.

By the time the first flare went up to signal the attack, the battle was already half won. The enemy thought they were fighting an army. They didn’t realize they were being hunted by ghosts. Then the sun came up and the stealth turned into a brawl. The battle for Biscari airfield was not a chess match. It was a fist fight with explosives.

The Germans defending the airfield were the Hermon Goring division, the elite of the Luwaffa. These were not old men and boys. These were fanatics. They unleashed a storm of mortar fire and machine gun bullets that turned the dry earth into a cloud of choking dust. The heat rose to over 100°. Men were sweating through their uniforms in minutes, their throats parched, their eyes stinging.

But where other units might have pulled back to regroup, the soldiers of the 45th pressed forward. They used a tactic known as marching fire. Instead of ducking for cover, they kept walking, firing their rifles from the hip, suppressing the enemy with sheer volume of aggression. It was terrifying to watch. A sergeant from the Chakaw Nation led a charge against a machine gun nest that had pinned down an entire company.

He didn’t wait for support. He ran in a zigzag pattern, dodging bullets and silenced the gun with a single grenade. Across the airfield, similar scenes played out. Men from the tribes of the southwest were engaging the pride of Hitler’s army at close quarters. It was brutal. It was bloody. The discipline of the German troops began to crack under the pressure.

They had never encountered an enemy that simply refused to stop coming. By early afternoon, the airfield was silent. The runways were littered with debris, but they were in American hands. Patton arrived later, his jeep kicking up dust. He looked at the bodies of the enemy, and he looked at the tired, dusty faces of the Native American soldiers cleaning their rifles.

He didn’t say much. He didn’t have to. The look in his eyes said it all. He had found his spearhead. But there is no rest for the weary in war. Before the dust had even settled at Biscari, the order came for the next objective. And this one was a nightmare. Bloody Ridge. It was a jagged spine of rock near SanStephano, a natural fortress that controlled the road to the coast.

The Germans had fortified it with everything they had left. They held the high ground, looking down the throat of the American advance. Standard military thinking said, “You don’t attack a position like that without massive artillery support.” But the element of surprise was gone and time was running out.

The 180th was told to take the ridge. They looked up at the steep exposed slopes. It looked like suicide. But these men saw cover where others saw only death. They broke into small teams shedding their heavy packs. They began the climb not up the main trails but up the sheer rock faces that the Germans thought were impassible.

One observer noted they climbed like mountain goats, finding footholds in the craggy stone that no boot should have held. When the firefight started, it was sudden and violent. The Germans were shocked to find American soldiers emerging from the cliff edge right next to their bunkers. The battle for Bloody Ridge was fought with knives, bayonets, and grenades.

It was a test of pure will. The inferior warriors drove the master race off the mountain foot by bloody foot. They took the ridge, but the cost was devastating. Men who had grown up together, who had left the reservation together, lay dead on the Sicilian stone. The survivors stood on the peak, looking out over the Mediterranean, gasping for air.

They were victorious, but they were isolated. Their radios were cutting out. Their ammo was low, and as the sun dipped below the horizon, they could hear the rumble of German tanks in the valley below, turning to counterattack. They had climbed to the top of the world only to find themselves alone in the dark. Word travels fast in war.

But fear travels faster. By the beginning of August, German intelligence officers were puzzling over intercepted reports from their own front lines. The weremocked soldiers, usually disciplined and stoic, were sending back frantic messages about a specific group of Americans. They called them the warriors without screams.

The Germans were used to American troops who yelled orders, whose radios crackled constantly and whose heavy boots crunched on the gravel. But these men from the 45th were different. They moved like smoke. Survivors of German patrols spoke of being watched by eyes they couldn’t see. They spoke of centuries found dead with their throats cut.

The only sign of the enemy being a single feather or a crude drawing left in the dirt, a psychological taunt from men who knew how to instill terror. The legend of the Apache Battalion was growing, spreading from the foxholes of Sicily all the way up the chain of command. Even the Allied high command began to realize they had something unique on their hands.

General Patton, who often viewed his soldiers as mere cogs in his great machine, paused to give credit where it was due. He famously remarked about the fighting spirit of the 45th. He said that if he could just keep them from going too wild, they were the finest combat soldiers he had ever seen. It was a backhanded compliment steeped in the prejudices of the time, but it was also an admission of a hard truth.

The Army manuals written at West Point didn’t teach men how to survive Bloody Ridge. The heritage of the American Southwest did, but with reputation comes a heavy price. When the generals needed a unit to do the dirty work, to clear a minefield, to storm a fortified farmhouse, or to patrol a valley swarming with panzers, they didn’t send the fresh troops.

They sent the Thunderbirds. Success didn’t earn them rest. It earned them harder missions. And as the campaign ground on, the men of the 180th began to realize that their reward for being the best was simply the opportunity to die first. In the brief moments of quiet between battles, when the artillery stopped pounding and the dust settled, the reality of their situation would sink in.

Soldiers would sit in the shade of olive trees, cleaning their M1 garrens and read letters from home. These letters were a lifeline, but they were also a stinging reminder of the world they had left behind. A corporal might read news from his mother in Oklahoma telling him that she had been refused service at a general store because of her skin color.

Another might read about the ongoing struggle just to vote in the state elections of New Mexico. Here they were thousands of miles from home, bleeding for a flag that in many ways still saw them as wards of the state rather than full citizens. It was the great American paradox.

Why fight so hard? Why charge a machine gun nest for a country that treats you like a stranger? The answer wasn’t found in politics or patriotism. You could see it in the way they shared their rations. You could see it in the way they dragged a wounded comrade out of the line of fire, risking their own lives without a second thought.

They didn’t fight for the generals in Washington. They didn’t fight for thelaws that held them down. They fought for the land itself, even if it was foreign land. And they fought for the man standing next to them. The warrior code of their ancestors dictated that once you are on the war path, you do not turn back. You protect your brother.

You honor your strength. This shared adversity forged a bond that was unbreakable. The racism they faced back home seemed distant when compared to the immediate reality of a German Tiger tank. But a new challenge was approaching. The army wasn’t just asking them to fight. They were asking them to race.

Patton had his eyes on the capital city of Polmo, and he was determined to get there before the British. He was about to push the Apache battalion to the absolute breaking point of human endurance. The race to Polarmo wasn’t a tactical maneuver. It was an ego trip for the generals, paid for in the sweat of the infantry. The order was simple.

Go fast. Don’t stop. The 45th Division was ordered to cover over 100 m of brutal mountainous terrain in a matter of days. The mechanized units had it hard, but the infantry had it worse. Trucks broke down in the heat. Tanks threw their tracks on the rocky roads, but the men of the 180th kept walking. This is where the walking army earned its name.

With blisters on their feet that turned into open wounds, with water cantens running dry in the scorching sun, they marched. They marched with a pace that stunned the observers. While other units collapsed by the roadside, exhausted, the indigenous soldiers drew on a reserve of stamina that went back generations.

They remembered the stories of their grandfathers who could run down a deer. They remembered the long migrations of their people. They turned the march into a rhythm, a transl-like state where pain was just background noise. They marched past the stalled convoys. They marched past the British units that had stopped for tea. When the enemy tried to slow them down with roadblocks or blown bridges, the Thunderbirds didn’t wait for engineers.

They scrambled down ravines and up the other side, carrying mortar plates and heavy ammunition boxes on their backs. When they finally crested the last hill and saw the city of Polarmo spread out before them, they looked like ghosts. Their uniforms were caked in white dust. Their eyes were hollow from lack of sleep. But they had done it.

They entered the city not as a parade, but as a conquering force of nature. The people of Polarmo threw flowers, but the soldiers were too tired to smile. They had broken the spirit of the enemy and the speed records of the army. General Patton got his glory. He got his headlines. But the men who had carried the spear knew the truth.

They had walked through hell to get there. Sicily was theirs. The island was conquered. But as they looked across the narrow straight of water toward the mainland of Italy, they knew the war wasn’t over. The mountains of Italy were higher. The winter was coming, and the Germans were waiting.

The campaign in Sicily lasted only 38 days, but it changed the men of the 45th Division forever. As the dust settled and the guns went silent for a brief respit, the Apache battalion had proven its point. They had taken the worst insults the enemy could throw. racial slurs, elite troops, fortified mountains, and they had crushed them all.

The skepticism of the American officers had turned into a quiet, almost superstitious reverence. No one questioned their discipline anymore. No one questioned if they could be controlled. They were the tip of the spear, sharp and deadly. But the tragedy of the story lies in what happened when the guns finally stopped for good in 1945.

These men who had liberated towns and defeated the Nazis returned home to a country that hadn’t changed as much as they had. They traded their M1 garands for the struggles of civilian life on the reservation. Many of them placed their purple hearts and silver stars in drawers, rarely speaking of what they had done. They went back to being secondclass citizens in the eyes of the law, even though they were first class heroes in the eyes of history.

But among themselves and in the memories of the men who served alongside them, the truth remained. They had shown the world that the warrior spirit is not defined by the color of a man’s skin, but by the fire in his heart. The legacy of the Thunderbirds and the indigenous warriors who led the charge is not just a footnote in a history book.

It is a testament to resilience. They fought two wars, one against Hitler and one for their own dignity. And they won them both. So the next time you see that yellow bird on a red diamond, remember the dust of Sicily. Remember the silence of the night patrol. And remember the men the US was afraid to unleash, who turned out to be the very men who saved the day. Thank you for watching.

If this story moved you, please share it with someone who needs to hear it. From wherever you are in this great world,stay safe, stay strong, and God bless.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.