One Quiet Question in a Prison Yard Shattered a German Woman in Chains—And Exposed the Secret Mercy Hiding Inside a Brutal War. NU

One Quiet Question in a Prison Yard Shattered a German Woman in Chains—And Exposed the Secret Mercy Hiding Inside a Brutal War

The rain in northern France didn’t fall like rain.

It fell like judgment—thin, relentless needles that found every gap in fabric, every crack in courage. It turned the prison yard into a slick patchwork of mud and puddles, and it made the world smell like wet rope, diesel, and old fear.

Private First Class Tommy Reece hated the rain because it made everything honest. In sunlight, men could pretend the war had rules. In rain, you saw the truth: faces hollowed by hunger, uniforms stiff with grime, boots that had marched too long and still weren’t done.

Tommy stood with his rifle slung and his collar turned up, guarding a line of prisoners being moved from a temporary holding pen to the converted schoolhouse that now served as an American POW processing station. The building had once held children, chalk dust, and songs. Now it held men in torn field-gray uniforms, a few wounded, and one prisoner who didn’t fit the line the way the others did.

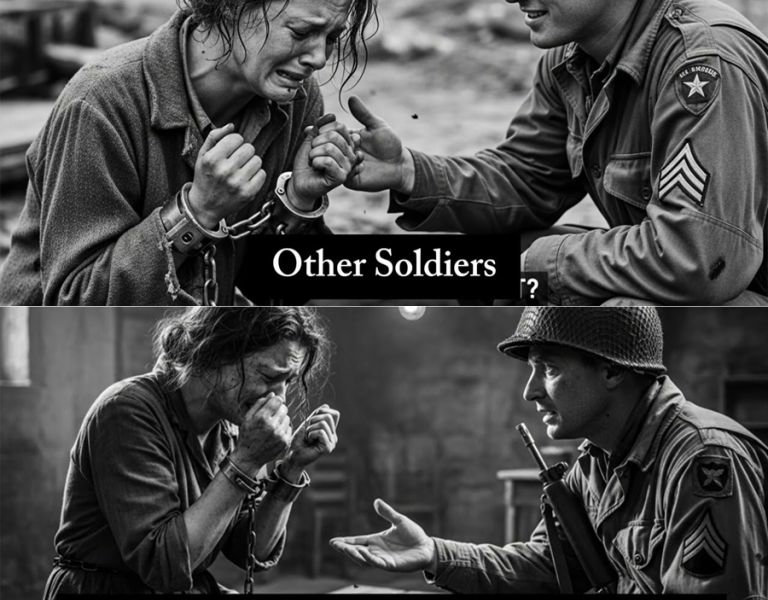

She was small—too thin to be called small the way people said it kindly. More like worn down to a minimum. Her coat hung off her shoulders. Her hair, once probably pinned neatly, had come loose in damp strands that clung to her cheeks.

And around her wrists were chains.

Not handcuffs. Not rope.

Chains, like somebody had dug them up from a medieval story and decided modern war deserved old punishments too.

A German woman prisoner.

Tommy had heard rumors about women in German uniform—auxiliaries, radio clerks, anti-aircraft crews. But seeing one in chains hit him like a wrong note in a song he didn’t understand.

The guards moving her were tired men with tired faces. One of them, Corporal Stinson, jerked the chain forward like he was leading a stubborn mule.

“Keep moving,” Stinson snapped.

The woman stumbled, caught herself, and kept walking without looking up. Her eyes stayed fixed on the mud like it was safer than meeting anyone’s gaze.

Tommy watched her pass and felt something in his chest tighten. Not sympathy exactly. He didn’t hand out sympathy easily anymore. It got you hurt.

But he felt… unease.

Chains weren’t standard. Chains were what you used when you wanted someone to feel less than human.

Tommy’s buddy beside him, a lanky kid from Georgia named Clint Harper, murmured, “Ain’t that somethin’.”

Tommy didn’t answer.

The line moved into the yard, where prisoners waited under a sagging canvas awning. Some sat on crates. Others stood, arms crossed, faces blank. A few stared at the woman in chains with a strange mix of pity and resentment, as if her presence complicated their own misery.

The American lieutenant overseeing intake, Lt. Mason Caldwell, stood near a table under a tarp, flipping through forms with the bored efficiency of a man trying not to think about what the war was doing to him. A medic sat nearby with a bag open, handing out bandages and aspirin like they were currency.

Tommy was assigned to perimeter watch, but he couldn’t stop tracking the woman with his eyes.

Stinson dragged her toward the table. “Found her with a radio,” he said. “Claims she was just a clerk. But she had a pistol in her kit.”

Caldwell glanced up, eyes taking her in quickly, then returning to his papers. “Name?”

The woman’s lips moved, but no sound came out at first. Her throat bobbed like she was swallowing words.

Finally, she said in accented English, barely audible: “Hilde. Hilde Schneider.”

Caldwell’s pen scratched. “Rank?”

She hesitated. “Auxiliary.”

Stinson snorted. “Auxiliary with a pistol.”

Hilde flinched.

Tommy felt his jaw tighten without his permission. He didn’t know her. She could’ve done terrible things. War made everyone capable of terrible things.

Still—chains.

The rain drummed on canvas. A prisoner coughed. Somewhere in the distance, a truck backfired, and half the men in the yard tensed like it was gunfire.

Caldwell looked up again, this time actually meeting Hilde’s eyes.

Her eyes were pale—gray-blue, washed out like the sky. They held exhaustion so deep it looked like an illness.

Caldwell’s expression changed, just slightly. Not softer, but more focused. Like he’d seen this kind of look before, not in enemies, but in his own men after a bad night.

He gestured toward the medic. “Check her.”

Stinson tugged the chain. “She ain’t wounded.”

“Check her anyway,” Caldwell said.

The medic—a calm Black sergeant named James “Doc” Baines—stood and approached Hilde with measured steps. His hands were clean despite the mud; he washed them constantly, as if cleanliness was one small rebellion against chaos.

He crouched slightly to be at her level. “You hurt anywhere?” he asked.

Hilde shook her head, eyes darting away.

Doc Baines studied her face, her trembling hands, the way she swayed as if the ground wasn’t steady. He didn’t touch her yet. He just observed, like a man reading weather signs.

Then he asked, in a voice so ordinary it almost didn’t belong in war:

“When was the last time you ate?”

The question landed like a punch.

Hilde stared at him.

For a moment, Tommy thought she hadn’t understood the English. Then her mouth opened, and her lips began to tremble. Her eyes blinked fast, like she was trying to keep something behind them from spilling out.

Doc Baines didn’t repeat the question. He simply waited, patient as a man holding a door open.

Hilde’s breath hitched.

Then—without warning—she made a sound that ripped through the yard like tearing cloth.

A sob.

Not a pretty cry, not a quiet sniffle. A raw, animal sound that came from somewhere deep inside her, as if she’d been carrying it for miles and miles and it had finally gotten too heavy.

She folded forward, chains clinking, shoulders shaking violently. Her knees hit the mud. She tried to cover her face with her bound hands and failed.

“I… I…” she gasped in German now, words tumbling out. “Ich kann nicht… ich kann nicht mehr…”

I can’t… I can’t anymore.

The yard went still.

Even the prisoners watching—men who had been enemies and were now simply tired—fell quiet. Something about a person breaking down wasn’t political. It wasn’t strategic. It was just human, and it made everyone uncomfortable because it reminded them of themselves.

Stinson swore. “Aw hell.”

Caldwell looked up sharply, irritation flashing—then fading when he saw Hilde on her knees.

Tommy’s hands tightened on his rifle strap. His throat felt thick.

Hilde’s sobs turned into desperate, shuddering breaths. “Bitte,” she whispered, not looking at anyone, pleading with the mud itself. “Bitte…”

Doc Baines reached slowly into his bag and pulled out a small ration bar, the kind that tasted like compressed sadness. He held it out in his open palm.

Hilde stared at it as if it were a trick.

Doc’s voice stayed gentle but firm. “Eat,” he said. “No tricks.”

Her chained hands shook too hard to reach properly. She fumbled, fingers slippery with rain. The bar fell into the mud.

Hilde let out a strangled cry of frustration and shame.

Tommy moved before he could think.

He stepped forward, ignoring Harper’s whispered, “Tommy—”

Stinson’s head snapped toward him. “Where you goin’, Reece?”

Tommy didn’t answer. He crouched near Hilde, careful not to touch her, and picked the ration bar from the mud. He wiped it against his sleeve, then held it out.

Hilde looked up at him, eyes red-rimmed, cheeks streaked with rain and tears. For a moment, her expression was pure terror, as if she expected a blow.

Tommy’s voice came out rough. “It’s fine,” he said. “Here.”

Hilde hesitated, then took it with her bound hands, biting into it like she feared it might vanish if she didn’t. She chewed fast, swallowing without tasting, desperate.

Doc Baines watched Tommy, then gave a small nod like a man acknowledging a choice.

Stinson muttered, “Soft,” but his voice lacked conviction.

Caldwell cleared his throat. “Get her inside,” he ordered. “Warm her up. Food. And—” He looked at the chains, jaw tightening. “Get those damn things off her. Use cuffs if you have to.”

Stinson blinked, surprised. “Sir?”

Caldwell’s eyes were hard. “That’s an order.”

Stinson grumbled but reached for a key.

As he unlocked the chain, Hilde flinched, expecting pain. But when the metal fell away, she sagged like the weight had been more than physical.

Tommy stood, mud on his knees, rain on his face, feeling strangely exposed.

Harper leaned close. “You okay?” he whispered.

Tommy didn’t know how to answer. He watched Hilde being guided toward the schoolhouse, still chewing like the food was an anchor.

He felt something shift in him, something he didn’t like because it made the war less simple.

Inside the schoolhouse, the air was warmer but smelled like wet clothes and disinfectant. Hilde sat on a bench near a chalkboard that still had faint arithmetic on it, ghost numbers from a life before war.

Doc Baines handed her a tin cup of broth. She held it with both hands, staring at the steam like it was magic.

Tommy was supposed to return to post, but Caldwell stopped him at the door.

“Reece,” Caldwell said quietly, “you speak any German?”

Tommy shook his head. “No, sir.”

Caldwell sighed. “Me neither. But she understands enough English. And she’s… not in good shape.” He rubbed his forehead. “I need someone to sit with her until transport comes. Make sure she doesn’t bolt or collapse.”

Tommy felt a flicker of protest—he wasn’t trained for this kind of duty. He was trained to shoot, to patrol, to survive.

But he nodded. “Yes, sir.”

Caldwell’s gaze sharpened. “You sure?”

Tommy surprised himself by saying, “Yes.”

Caldwell nodded once. “All right. Don’t get friendly. But don’t get stupid either.”

Tommy returned to the bench area, standing near Hilde without looming too close. He kept his rifle slung, hands visible, posture neutral.

Hilde sipped the broth, then lowered the cup, staring at her knees. Her shoulders still trembled occasionally, aftershocks of the breakdown.

After a while, she spoke without looking up. “You… you picked it up.”

Tommy blinked. “The food?”

She nodded. “You did not… you did not let me…” She struggled for words, then made a helpless gesture. “Like animal.”

Tommy swallowed. He wasn’t used to being thanked by enemy prisoners. It felt like stepping on ice.

“It was just food,” he said.

Hilde’s laugh was bitter and small. “In war,” she said softly, “food is never ‘just.’”

Tommy didn’t argue.

Silence stretched. Rain tapped the windows.

Then Hilde spoke again, voice quieter. “I was not soldier,” she said. “Not like… front. I was radio. Messages.”

Tommy’s mind flashed to friends lost because of messages sent, coordinates called in, orders relayed. The war was a chain of small actions that made big deaths.

He kept his voice flat. “Radio can kill people.”

Hilde flinched, then nodded. “Yes.”

She took another sip of broth, hands shaking less now.

Tommy stared at the chalkboard, at the faint numbers. He thought of children learning sums while outside men learned how to take lives.

He asked, without meaning to sound kind, “How long since you ate?”

Hilde’s throat bobbed. “Two days,” she whispered. “Maybe three. I stopped counting because… it makes worse.”

Tommy felt anger flare—not at her, but at the war’s casual cruelty. Then anger flickered into something else: shame, because he was part of the machine, too.

He shifted his weight. “Why were you in chains?”

Hilde’s eyes went distant. “I ran,” she said simply.

Tommy frowned. “Ran? From who?”

Her voice dropped. “From my own.”

The words hung heavy.

Hilde finally looked at him. Her eyes were clearer now, but still haunted. “They said I was coward,” she said. “They said I must be example. They put chains to show others what happens when you stop believing.”

Tommy’s chest tightened. He thought of his own side’s punishments, of rumors about deserters, of how every army had its own ways of making fear into discipline.

“Did you desert?” he asked.

Hilde’s jaw trembled. “I… I could not send more messages,” she whispered. “Not after… after the village.”

Tommy waited.

Hilde’s voice broke slightly. “A village near Caen. We relayed coordinates. Then later I saw… I saw smoke. I saw people running. And a child with no shoes.” She swallowed hard. “I told myself it is not my hands. It is only words. But words… they are bullets too.”

Tommy felt his stomach twist. He’d said something similar once, after a bombardment: We didn’t kill them. The shells did. It had sounded like a lie even then.

Hilde stared at her cup. “So I ran,” she said. “And then your soldiers found me.”

Tommy didn’t know what to do with that story. It made her both guilty and not-guilty, both enemy and human. The war didn’t like complicated people. It preferred targets.

He cleared his throat. “You broke down when Doc asked about food.”

Hilde’s hands tightened around the cup. “Because it was… first time someone asked me something that was not accusation,” she said. “Not ‘Where is your unit?’ Not ‘What did you do?’ Just… ‘Did you eat?’”

Her eyes filled again, but she blinked hard, holding herself together. “It made me remember I am… person.”

Tommy felt his own throat tighten. He looked away quickly, ashamed of the emotion.

Outside, a truck engine rumbled. Orders shouted. The war was impatient.

Hilde whispered, almost to herself, “I am sorry.”

Tommy’s jaw tightened. He didn’t know if she meant sorry for being German, sorry for the village, sorry for existing in the wrong uniform.

He said, rougher than he intended, “Don’t say it to me. Say it to the ones who can’t hear you.”

Hilde nodded slowly, tears slipping anyway.

When the transport finally arrived—two MPs with paperwork and a tired look—Hilde stood shakily, coat wrapped tighter, wrists now in standard cuffs instead of chains.

Before she was led out, she stopped and looked at Tommy.

“I do not know your name,” she said.

“Reece,” Tommy replied.

She nodded as if committing it to memory. “Reece,” she repeated carefully. “You asked me… you did not laugh. You did not spit. You gave food.”

Tommy swallowed. “It was a ration bar.”

Hilde’s eyes held his. “For you,” she said softly, “it was bar. For me… it was question. And answer.”

One of the MPs tugged her arm. “Move it.”

Hilde turned, then hesitated again, and said in English that was clumsy but clear:

“Please… do not become chain-man.”

Then she was gone into the rain.

Tommy stood in the schoolhouse doorway, watching her disappear into the gray yard, mud sucking at boots, war grinding on.

Harper came up beside him. “What’d she mean?” he asked.

Tommy stared at the empty space Hilde had left behind. He thought of chains, and of questions that could break someone faster than fists.

He answered quietly. “She meant… don’t let the war make you into the kind of guy who thinks chains are normal.”

Harper was silent.

Outside, the rain kept falling like judgment.

Inside, the chalkboard still held children’s arithmetic, stubborn and innocent.

And Tommy Reece stood there with mud on his knees and a taste of ration bar in the air, realizing the strangest thing he’d learned in all of Europe:

Sometimes you don’t change a war with a gun.

Sometimes you change one small piece of it with a single question that remembers a person is hungry.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.