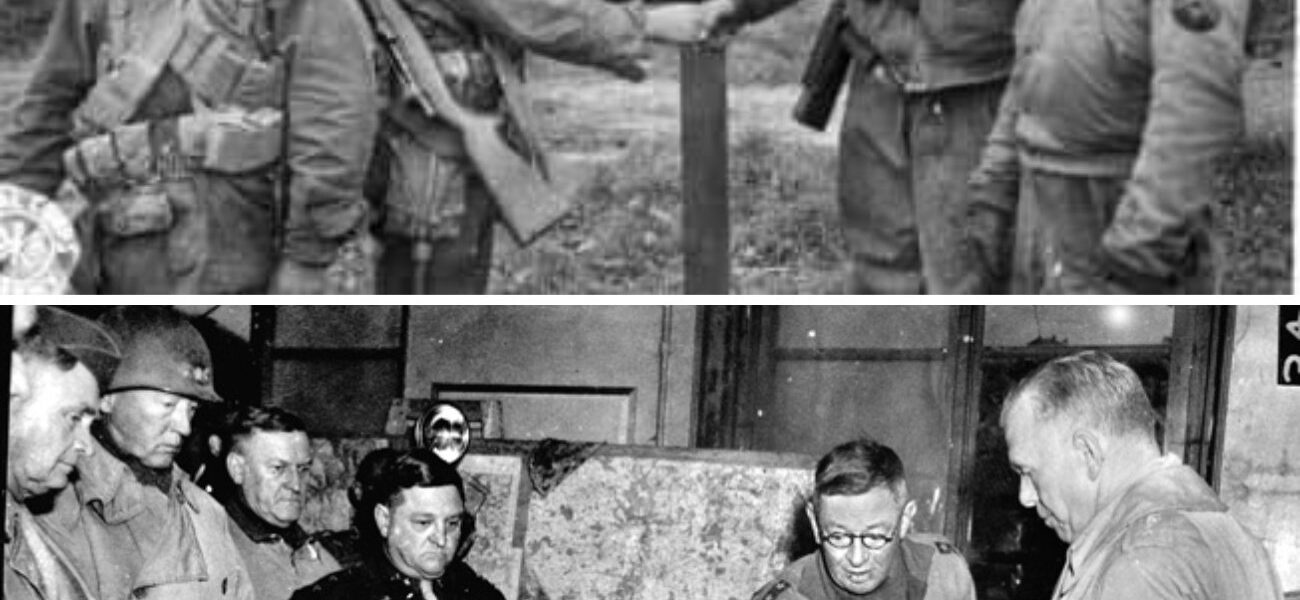

November 22, 1944, SHAEF Headquarters in Reims: What Patton Did at Metz — and What Didn’t Add Up. NU

November 22, 1944, SHAEF Headquarters in Reims: What Patton Did at Metz — and What Didn’t Add Up

Metz in the Rain: What Eisenhower Heard When Patton Took the “Impregnable” Fortress

This article is a dramatized reconstruction based on the narrative you provided, written in a documentary-news style.

On November 22, 1944, the weather over northeastern France felt like an extra enemy. Cold rain hammered the windows at Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, and the mud outside seemed capable of swallowing trucks whole. Inside, General Dwight D. Eisenhower worked through the least glamorous part of a winter campaign: supply distribution.

His coffee had gone cold. The reports on his desk were all numbers—fuel tonnages, truck allocations, rail capacity, ammunition forecasts—each line an argument with the calendar. The coming months promised snow, frozen roads, and stalled offensives. Eisenhower was calculating what could move, what could not, and what had to be rationed.

Then Captain Harry Butcher came in without knocking.

Butcher did not enter that way unless something had shifted. Eisenhower looked up and read his aide’s face the way commanders learn to read weather.

“General,” Butcher said, “Third Army is reporting Metz. Forts are surrendering. Fort Driant surrendered this morning.”

Eisenhower’s pen stopped. He set it down, carefully, as if sudden motion might make the words less true.

“That’s impossible,” he said.

He reached for the calendar and flipped back. November 8 was the date Patton had begun the assault. Eisenhower counted forward with his thumb. Ten days. Ten.

In a drawer marked for the things that were not supposed to travel beyond his desk, he kept a thick folder with a stark title: British Joint Intelligence Committee—Assessment of Fortress Metz, dated October 18, 1944. He opened it to the summary page and read aloud, as if the act of saying it could still anchor reality.

“Fortress Metz represents the most formidable defensive position between the Rhine and Paris,” he read. “Recommend bypass strategy. Direct assault estimated 180-day operation. Casualties forty-five to fifty-five thousand. Minimum eight divisions with full air support.”

Eisenhower looked up at Butcher. “British intelligence estimated six months.”

Butcher said nothing. The rain kept tapping at the glass.

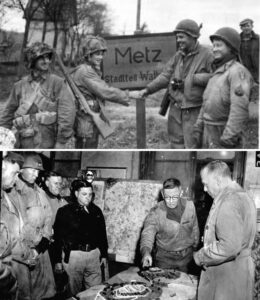

A few minutes later Lieutenant General Walter Bedell Smith, Eisenhower’s chief of staff, entered carrying a thinner folder—Third Army after-action report, the kind of document meant to close arguments, not start them.

“Sir,” Smith said, “I verified with G-2. Every major fort in the Metz complex has surrendered or been captured. The city is ours.”

Eisenhower scanned the first page. “Metz secured,” it read. “Duration 8 November through 22 November.” He read the next line twice. “Casualties: 2,897.” Another line listed the names of forts—Driant, Jeanne d’Arc, and the satellite positions—each reduced, neutralized, silenced.

He held the British assessment in one hand and Patton’s report in the other, flipping between them like a man comparing two clocks that should agree.

“Walk me through this again,” he said. “We were told Metz was impregnable without a months-long siege.”

Smith’s voice stayed careful. “Apparently so, sir. Third Army is already moving units east toward the Saar.”

Eisenhower stood and walked to the window. Outside, the headquarters yard was a churned field of brown water. Somewhere beyond that mud lay the Moselle River and a city the Germans had fortified in concentric rings for decades. Twenty-eight interconnected forts. Ten-foot-thick concrete. Underground tunnels. Gun positions that could reach fifteen miles. Metz had been built, expanded, and modernized from the Franco-Prussian War through the First World War, designed to be stubborn even when surrounded.

In Eisenhower’s mind, “Metz” was not a headline. It was a logistical sinkhole. Every day spent outside its forts was a day of burning fuel and ammunition that could not be replaced easily in November. Every week spent in siege lines was another week closer to winter’s hard stop. And every casualty outside Metz would be a casualty not available for the next push.

“Ten days,” he murmured, as if repeating it might reveal a hidden trick.

Smith, watching him, allowed the smallest hint of a smile. “Apparently not impossible, sir.”

Eisenhower turned back to the desk and looked at the two folders again. One predicted six months and fifty thousand casualties. The other reported ten days and fewer than three thousand.

He did the subtraction that mattered most to a coalition commander: Patton’s speed had just turned a fortress into momentum. But momentum, Eisenhower knew, could be as dangerous to manage as it was useful to create.

He picked up the telephone and told the operator to connect him to Third Army headquarters in Nancy.

The line clicked, rang, and was answered by an orderly voice. Another click, then the familiar sound of George S. Patton as the story imagines him—confident, almost cheerful, as if bad weather and fortified cities were simply more tasks to be completed.

“Ike,” Patton said, “I was wondering when I’d hear from you.”

Eisenhower kept his tone professional. “George, congratulations are in order. Metz in ten days is remarkable.”

Then he added what mattered to headquarters more than any compliment. “Now tell me how you did it.”

Patton’s reply, in this retelling, came without hesitation. “Ike, you know I don’t like to brag, but since you asked: speed, aggression, and a healthy disregard for British intelligence estimates.”

Eisenhower glanced down at the October 18 assessment. “I’m reading it right now,” he said. “Twenty-eight interconnected forts. Ten-foot concrete walls. This wasn’t supposed to be possible without a prolonged siege. The recommendation was to contain it, not assault it directly.”

Patton’s voice sharpened into the tone Eisenhower knew well—the tone that meant Patton was about to explain why everyone else’s logic was too slow. “The assessment also said the Germans had fifteen thousand well-supplied defenders,” Patton said. “They had maybe nine thousand who were half starved, short on ammunition. Intelligence is often just educated guessing, Ike.”

Eisenhower pressed the point. “You bypassed standard siege protocols. You didn’t isolate each fort. You didn’t wait for heavy artillery to be positioned by the book. The doctrine says you establish siege lines, cut supply routes, then reduce strong points one at a time over weeks.”

“The doctrine was written by men who never had to take Metz in November with limited supplies and a ticking clock,” Patton said. “I hit them everywhere at once. They didn’t know where to concentrate their defense.”

Eisenhower heard the risk behind the confidence. “You risked encirclement,” he said. “If they’d counterattacked while you were spread across multiple assault points—if they coordinated a breakout from the interior forts while you were engaged on the perimeter—”

“But they didn’t,” Patton cut in. “Because I didn’t give them time to organize one. Ike, you can strangle a fortress slowly, methodically, by the book, or you can hit it so hard and so fast it doesn’t have time to fight back. I chose speed.”

Eisenhower’s mind, trained to manage the entire front, could not ignore the “if.” “George, you understand if this had gone wrong—if you’d gotten an entire corps pinned down in November mud outside Metz with winter coming—then you’d have my resignation on your desk, and I’d deserve it.”

Patton, in the story, did not hesitate. “But it didn’t go wrong. It worked. We’re across the Moselle. Metz is ours, and I’m already positioning for the Saar crossing.”

There was a pause long enough for Eisenhower to rub his temple.

“One of these days,” Eisenhower said, “your confidence is going to write a check your army can’t cash.”

Patton’s reply was instant. “Not today, though. Anything else, Ike?”

Eisenhower chose his last words with care. “Just this, George: every time you pull off something impossible, it raises expectations for the next impossible thing. There are limits.”

Patton’s voice stayed calm, certain. “Not for Third Army. There aren’t.”

Eisenhower hung up. He stared at the map on the wall as if it might argue back. Then he said, to no one in particular, “He actually did it.”

Smith, still in the office, had one more file. “Sir, there’s something else. Our liaison officer saw Patton’s diary entry about the call.”

Eisenhower looked up, wary.

Smith read it, quoting the line the story gives him. “‘Ike called to congratulate me on Metz. I could tell he was equal parts impressed and annoyed. Good.’”

Eisenhower shook his head slowly. “Of course he wrote that.”

A second folder appeared on the desk. This one was not about Metz as a military objective, but about Metz as a political event.

“Sir,” Smith said, “we’re receiving inquiries from other commands. Questions about resource allocation. Questions about why their objectives are taking longer than Patton’s.”

This was the problem Eisenhower had felt even as he congratulated Patton. In coalition warfare, success is not only celebrated. It is measured, compared, and used.

Within a day, in the story’s timeline, London felt the shock wave. The British Joint Intelligence Committee received a formal inquiry from SHAEF: review the October 18 assessment in light of Third Army securing Metz in ten days with under three thousand casualties.

In the imagined scene, a senior analyst—Brigadier Kenneth Strong—spread maps and reports across his desk. The assessment had been thorough in the way good intelligence often is. It referenced German defensive doctrine. It referenced historical siege data. It referenced reconnaissance of fortifications and testimony about garrison strength. It built a conclusion the way professionals build conclusions: carefully.

Then Strong placed Patton’s after-action report beside it and saw the words that turned careful into awkward: “All forts neutralized.”

His response, drafted in formal language, was also an admission. The assessment, he wrote, had assumed conventional siege tactics: establishment of siege lines, systematic reduction, long coordination of heavy artillery and air support. Patton had used unconventional methods, simultaneous assault on multiple fortified positions, sustained offensive pressure despite weather. The psychological impact of aggression appeared to have exceeded the defensive capacity of the garrison. Revision recommended. Methodology under review.

Strong, in the story, understood the blunt translation. British intelligence had not accounted for Patton being Patton.

Back in France, the political ripples grew. A message arrived from Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery suggesting, with all the politeness of a professional rival, that if Patton required only ten days for Metz, perhaps Third Army required fewer supplies than currently allocated—and that resources might be better used on the northern thrust.

Eisenhower’s staff stared at the message. Smith spoke first. “Sir, if we reduce Patton’s supplies based on his success, we’re punishing him for being effective.”

Eisenhower drafted his response with the bluntness of a man trying to prevent a new kind of stupidity. Metz fell, he wrote, because Patton had adequate supplies and used them aggressively. SHAEF was not interested in testing whether fortresses fell faster when starved of fuel and ammunition.

Yet Eisenhower also knew the damage could not be fully undone. Patton’s victory had created a standard that could be misread as a baseline. Success became a weapon in the hands of competing commands, and in coalition warfare, politics and logistics are rarely separable.

Meanwhile, Patton treated Metz not as a finale but as momentum. His units were already shifting east, preparing for the next push before the winter could fully close.

On November 25, far from the rain in France, a report landed on the desk of General Alfred Jodl at German high command in East Prussia. The first line forced him to stop and read it twice.

Fortress Metz has fallen.

Metz was supposed to anchor the West Wall defenses for the winter. Metz was supposed to buy time for reinforcement, reorganization, and survival. If Metz could fall in days, then the German calendar—already short—became shorter.

That is what Eisenhower had sensed at the window. Metz was not simply a dot on a map. It was a message, transmitted through mud and rain, that the “impossible” could sometimes collapse under speed.

The challenge for Eisenhower was not whether to praise Patton. That was easy. The challenge was how to manage the consequences of a victory that made everyone else’s limits look like choices.

To understand why the news felt like a violation of arithmetic, it helps to remember what “Metz” meant to planners in October. The name did not refer only to a city. It referred to a fortress region built to dominate the Moselle crossings and punish anyone who tried to force a river line in front of it. Its forts were not single buildings but systems: reinforced casemates, concrete gun blocks, wire, trenches, tunnel networks, and overlapping artillery fields.

A conventional siege treats such a place like a locked door: you surround it, cut it off, and then, slowly, you force it open. The October assessment, as the story presents it, assumed that model. It assumed time would be spent on isolation, on artillery preparation, on systematic reduction of strong points. It assumed that the defenders would have time to coordinate, to ration ammunition, to plan breakouts, and to exploit any attacker who overextended.

Patton’s method, in the phone call, describes a different theory: treat the fortress like a man holding his breath. Do not give him time to inhale.

“Hit them everywhere at once,” Patton says in the retelling. It is a phrase that reads like bravado, but it contains a logic that staff officers can diagram. Multiple simultaneous attacks force defenders to guess where the decisive point is. They thin out. They misread. They spend energy reacting instead of shaping.

It is also a gamble. Simultaneous pressure can become simultaneous vulnerability. If defenders strike the attacker’s seams, if interior positions coordinate with perimeter positions, if counterattacks find the weak point, then the attacker’s speed turns into chaos.

Eisenhower understood that gamble immediately. That is why his questions were not purely admiring. They were the questions of a man who has to explain the costs if the gamble fails. Patton, in this telling, answers with the only currency he consistently trusted: time. He believed that if he moved fast enough, the enemy would not have time to exploit risk.

It is possible to see the same logic in Eisenhower’s own life, though expressed differently. Eisenhower was a coalition manager. He moved slowly on paper so that the front could move quickly in reality. He watched calendars the way Patton watched roads. He knew that an army could not live on enthusiasm alone. It had to eat, fuel, and repair itself.

Metz, then, put two styles of leadership into direct contact. Patton’s style created shock, motion, and opportunities. Eisenhower’s style absorbed that shock and tried to make it sustainable across multiple armies with multiple governments behind them.

That is why, in this story, Eisenhower’s most important “line” is not a joke or a praise. It is the warning he gives Patton about expectations: every impossible victory becomes a new demand for the next impossible victory.

It is easy, after a surprise success, to assume the miracle was the method. It is harder to admit the miracle might have been the man.

In the days after Metz, in this dramatized reconstruction, the alliance begins asking questions that sound logical but are rooted in envy. If Patton took Metz in ten days, why can’t someone else take their objective in ten days? If Patton suffered under three thousand casualties, why should anyone else need more? If Patton did it in rain and mud, why does weather matter?

These questions ignore context. They ignore luck. They ignore the enemy’s condition. They ignore the fact that “fast” is not a universal solution. But war, like politics, is full of people who mistake an example for a rule.

That is what made Montgomery’s message dangerous. In a coalition, supply is influence. If Patton’s success could be used as proof that Third Army required less fuel, then Patton’s speed could be turned into a reason to starve him.

Eisenhower pushed back because he understood that starving a commander to “test” whether his success was repeatable is not strategy. It is sabotage disguised as fairness.

And still, the comparisons continued, because comparisons are what coalitions do. Patton’s win became a measuring stick.

In London, intelligence analysts revisited their assumptions. They may have been wrong about Metz’s timeline, but they were not wrong about the nature of the fortifications. The question became: how much of an “impregnable” fortress is concrete, and how much is the defender’s confidence? How much of a siege is engineering, and how much is psychology?

The retelling answers with the language of pressure. Sustained aggression can do what artillery cannot: it can convince a garrison that the world is collapsing faster than it can be repaired. A fortress’s walls matter less if the men behind them believe the situation is already hopeless.

That idea is uncomfortable for planners because it is hard to quantify. You can count divisions. You can count shells. You can count feet of concrete. It is harder to count how quickly fear spreads through a defensive network when every point is under threat.

Metz, as the story frames it, is a reminder that the battlefield punishes certainty. The October assessment was certain that Metz could not be reduced quickly. Patton’s report suggested the opposite. The truth was not that the assessment was foolish. The truth was that the assessment assumed a kind of war that Patton refused to fight.

Eisenhower, as the man responsible for the whole front, heard the victory through a different filter. He did not only hear “Metz is ours.” He heard, “Every commander will now be compared to Patton.” He heard, “The alliance will argue about supplies using Patton as an argument.” He heard, “Berlin will redraw its winter plan.”

That is why his congratulation on the telephone carried a second tone, a warning. A victory that arrives “too fast” can be disruptive. It can make sensible caution look like laziness. It can make measured planning look like fear. And it can tempt leaders to demand more “impossible” outcomes in the next week, and the week after that.

In the days after Metz, staff officers began asking the question headquarters officers always ask when a result surprises them: is this repeatable? Is it a method, or is it a man? The British Joint Intelligence Committee, according to the dramatized response, concluded that their methodology had assumed a conventional siege and a conventional opponent. Their new problem was that Patton’s strength was not only his aggression, but his ability to change the questions faster than the enemy could answer.

For Eisenhower, the lesson was not to throw away doctrine. Doctrine exists because most commanders cannot win by improvisation alone. The lesson was to recognize when doctrine becomes a brake at the exact moment speed is the strategy. Patton had gambled that Metz could be made to collapse under simultaneous pressure. He had also gambled that the Germans could not coordinate a clean breakout or counterattack while being hit everywhere at once.

Those gambles paid off. But Eisenhower knew—perhaps better than Patton—that a winning gamble can encourage the next gamble. He also knew that the men who would pay for a failed gamble would not be sitting in warm offices with maps. They would be in the mud.

The story’s final twist is that the “impregnable” label did not survive contact with the outcome. The moment Metz fell, “impregnable” became a word people said with a smile. It became a warning about overconfidence in paper estimates and an argument for remembering that intelligence, however professional, is still a snapshot of a moving target.

In that sense, what Eisenhower “said” was less a single line than an instinctive reaction that every strategist recognizes: the moment you learn the impossible has happened, you must immediately re-measure what you thought was possible—because the battlefield will not wait for you to adjust.

And the rain kept falling on Metz.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.