- Homepage

- Uncategorized

- Japanese Nurses Watched Americans Treat Enemy Children Before Their Own Soldiers. NU

Japanese Nurses Watched Americans Treat Enemy Children Before Their Own Soldiers. NU

Japanese Nurses Watched Americans Treat Enemy Children Before Their Own Soldiers

The Shock of Abundance

March 14th, 1945. A day Lieutenant Hanako Tanaka would never forget.

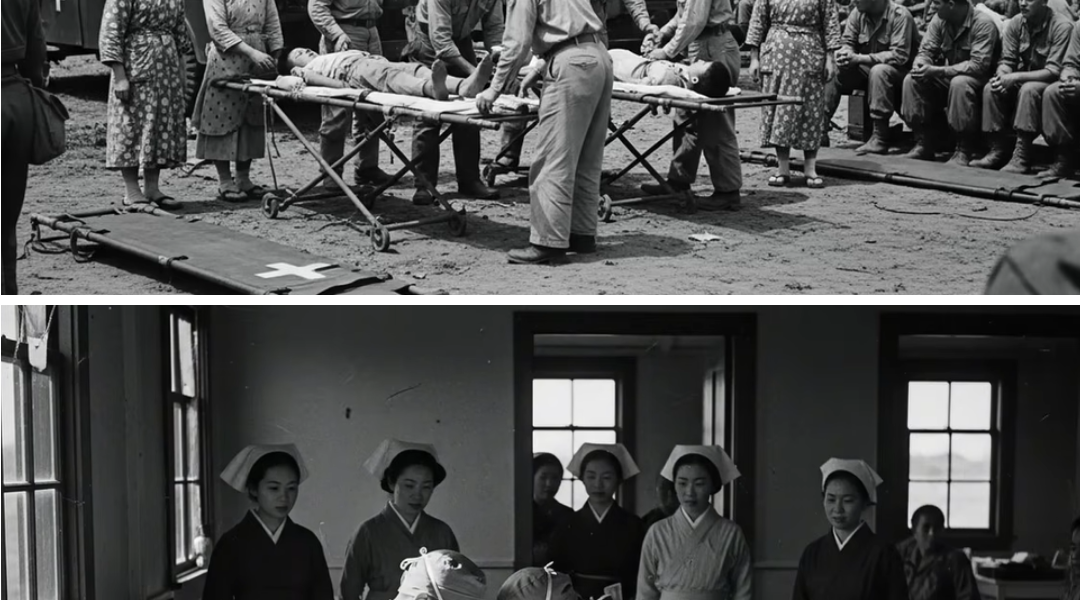

Standing at the entrance of the American field hospital on Saipan, she clutched her medical clipboard with white knuckles, her eyes struggling to comprehend the impossible scene before her.

Children. Japanese children. Lying on pristine white beds, receiving treatment from American military doctors. The same enemy forces who, according to Imperial propaganda, bayonetted infants and tortured civilians without mercy.

What Lieutenant Tanaka saw defied 23 years of carefully constructed national indoctrination, shattering the foundation of everything she had been taught to believe. She had been captured three weeks earlier during the final desperate days of the Battle of Saipan. Now, under guard but serving as a medical translator, she watched American doctors administer penicillin, a medicine so scarce in Japan that even high-ranking officers often died from treatable infections.

“They’re treating these Japanese children before their own wounded,” she whispered to nurse Yumikosato, who stood frozen beside her. The words felt foreign in her mouth, an impossible truth her mind struggled to accept.

Beyond the children’s ward, Lieutenant Tanaka could see rows of American soldiers waiting patiently for treatment, their uniforms still caked with the mud and blood of battle. This cannot be happening, she murmured, her voice barely audible above the gentle hum of electric fans. Another luxury unimaginable in Japanese field hospitals.

The American Chief Medical Officer, Major Robert Wilson, approached with a clipboard. “Lieutenant Tanaka, we have four more children from the caves in the northern sector. We need your help explaining the procedures to them.”

His tone was matter-of-fact, as though the preferential treatment of enemy children was the most natural thing in the world.

In that moment, standing beneath the cool breeze of electric fans, with the scent of antiseptic—not gangrene—filling her nostrils, Lieutenant Tanaka began to understand that she had been fighting a different enemy than the monsters described in Imperial broadcasts. This revelation would be the first of hundreds that would systematically dismantle everything she thought she knew about America, about Japan, and about the war that had consumed the Pacific for nearly four years.

Lieutenant Tanaka had been part of a generation raised on the belief that Japan’s divine mission was to defeat the “barbaric” Americans. In schools, at home, on the radio—everywhere she turned, the message was the same: the Americans were savages, brutal and cruel. They did not value life, especially the lives of their enemies.

Yet, here she was, witnessing the impossible.

As part of her duties as a translator, she had access to observe the medical operations on Saipan. It was an education she could never have anticipated. Each new day brought revelations that would challenge her worldview beyond measure.

On her third day of captivity, Major Wilson took Lieutenant Tanaka to the hospital’s supply depot. A series of pre-fabricated warehouses stood as proof of American resourcefulness. Inside, Lieutenant Tanaka stopped in her tracks. Row upon row of medical supplies stretched before her, stacked from floor to ceiling in perfect order. Penicillin, blood plasma, surgical instruments, all in abundant supply.

“This is for the entire Pacific theater?” she asked, struggling to keep her voice steady.

“No, this is just for Saipan,” Major Wilson replied. “Each island operation has its own supply chain.”

Lieutenant Tanaka couldn’t fathom the scale of it. The Japanese Medical Corps might have a few hundred doses of penicillin reserved for the highest-ranking officers, yet here it was being administered to enemy civilians and prisoners without a second thought.

Her hands trembled as she wrote the figures in her notebook: 70,000 doses of penicillin in stock, with another 100,000 coming in tomorrow’s shipment. The disparity between the two nations’ resources was growing clearer by the hour.

A few days later, Lieutenant Tanaka witnessed an American field surgery. A 19-year-old private from Nebraska was being treated for shrapnel wounds. The surgical team was efficient, working under bright electric lights with equipment she had only read about in medical textbooks. There were six personnel tending to this one soldier—an enlisted man. In Japan, such a soldier might receive a bandage and a place to die with dignity, but never such extravagant treatment.

“What’s his prognosis?” Lieutenant Tanaka asked, almost afraid to hear the answer.

“He’ll be back on limited duty in about three weeks,” the surgeon said, as though the concept of saving a young soldier was a matter of routine.

Three weeks of recovery. The resources, the personnel, the effort—no amount of spiritual strength could overcome this industrial capacity. Japan, with its dwindling supplies, was now fighting an enemy that not only had the material resources but also the compassion to care for its enemy soldiers with the same diligence they would their own.

The cognitive dissonance was overwhelming. Lieutenant Tanaka had grown up believing in the superiority of the Japanese spirit, the power of sacrifice and selflessness. But what she was seeing in the American field hospital was different. It was not just about physical resources—it was about a philosophy of life. A belief that all lives were worth saving, even those of enemies.

A few days later, she witnessed the treatment of a Japanese lieutenant who had been captured after hiding in a cave for six days. The American doctors worked to save his life, administering fluids and antibiotics. The lieutenant’s wounds were serious, but with American resources and care, he would survive.

“Will he make it?” Lieutenant Tanaka asked, already knowing the answer.

“Unless there are complications, he’ll be eating solid food in a week,” the doctor replied confidently.

The idea that a soldier who had fought against Americans could be saved so easily, with such care and precision, left Lieutenant Tanaka speechless. She had spent years fighting to uphold the honor of her nation, only to find herself face-to-face with a new reality: a nation that valued every life, regardless of its allegiance.

As the weeks passed, Lieutenant Tanaka found herself observing more and more of the American way of life. The care for prisoners. The treatment of civilians. The luxury of a full meal, a real bed, and clean clothes. These were things she had been told were impossible for an enemy to offer, yet here they were.

One evening, after another long day of witnessing the care given to Japanese prisoners, she sat down to write in her diary.

“What I am seeing cannot be reconciled with what I have been told,” she wrote. “Either everything I have witnessed is an elaborate deception, or everything I have been taught is a lie.”

It was becoming clear to Lieutenant Tanaka that the true enemy she had been fighting was not the one she had imagined. It was not the savage, unfeeling Americans her government had portrayed. The true enemy was the industrial might that could produce so much, that could waste so much, that could afford to value every human life.

The surrender came on August 15th, 1945. Lieutenant Tanaka gathered with the other Japanese medical personnel, listening to Emperor Hirohito’s announcement. They had lost the war—there was no doubt about it.

But for Lieutenant Tanaka, the realization had already set in months earlier. The war was not lost on the battlefield. It was lost in the factories, in the fields, in the factories and shipyards of America, where production and abundance had outpaced everything Japan could muster.

Her experiences as a prisoner of war had given her insight into the true nature of Japan’s defeat. It was not a failure of spirit or courage—it was a failure of resources. America’s victory was not written in the numbers of battles won, but in the sheer abundance that allowed them to save lives, even those of their enemies.

Lieutenant Tanaka’s life, and Japan’s post-war transformation, would never be the same. The lessons she learned on Saipan would not only help rebuild Japan’s health system but would also help reshape its entire economic and industrial outlook. The shock of abundance had shown her the true nature of power: not in military might, but in the capacity to care for all, even those who were once considered enemies.

As the years went on, Lieutenant Tanaka became an influential public health administrator. She would often recall the lessons learned during those months of captivity—the lessons that had reshaped her understanding of the world.

In her memoir, she reflected on how her view of America had been irrevocably altered: “We entered the war believing that America’s material wealth had made its people soft and decadent, incapable of withstanding hardship or sacrifice. What we discovered instead was that this abundance had created a society that could afford humanity even toward its enemies. The ultimate luxury and, paradoxically, the ultimate strength.”

For Lieutenant Tanaka, the shock of abundance was a revelation that not only transformed her but ultimately helped rebuild a new Japan—one that would rise from the ashes of defeat and become a partner in prosperity with the very nation it once fought against.

And so, the true victory of World War II was not in the battlefields of the Pacific, but in the way the world would rebuild, guided by the strength that came not from war, but from the abundant resources and compassion of the American soldiers who showed Lieutenant Tanaka—and the world—that some wars are won with generosity, not weapons.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.