- Homepage

- Uncategorized

- Japanese Nurses Captured — Stunned by Respect From US Guards – Banned Story. VD

Japanese Nurses Captured — Stunned by Respect From US Guards – Banned Story. VD

Japanese Nurses Captured — Stunned by Respect From US Guards – Banned Story

The Changing Tide of War: A Nurse’s Journey

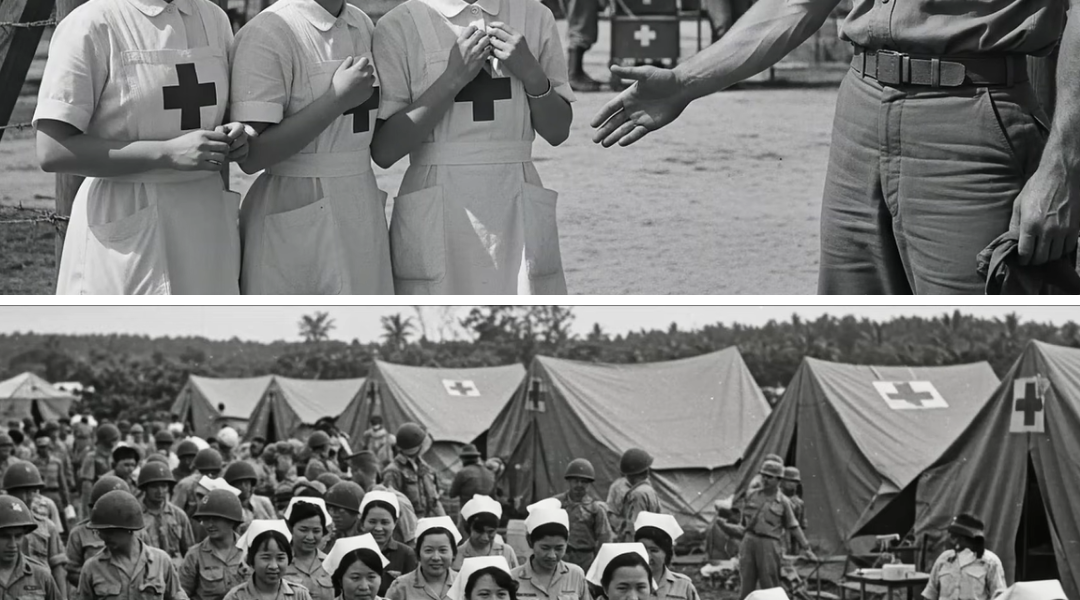

It was a searing morning on June 22nd, 1945, in the Pacific theatre of World War II. Lieutenant Yumiko Takahashi stood frozen at the entrance to the American Field Hospital on Okinawa, her eyes fixed on the scene in front of her. The young Japanese nurse, once part of the Imperial Army’s medical corps, had expected to witness the brutality of her captors, to be humiliated as the enemy had promised her. What she saw instead shattered everything she had been taught to believe about the United States.

Before her stood a scene unlike anything she had ever imagined: American doctors and nurses, moving with an unspoken grace, tending to the wounds of her compatriots, just as they had tended to their own. The wounded Japanese soldiers, some of whom had been fighting against the Americans just days earlier, were receiving medical treatment without hesitation or malice. It was a sight so foreign to Yumiko’s understanding of the enemy, a stark contradiction to the Nazi-inspired propaganda that had painted Americans as savage, unworthy of any compassion.

But it was one encounter that would truly challenge her deeply ingrained beliefs. A young American nurse, with a friendly smile and poor Japanese pronunciation, approached Yumiko. In a gesture of kindness, she said, “You are safe now. We respect medical personnel of all nations.” The words, so simple yet so genuine, filled Yumiko with an overwhelming sense of confusion and disbelief. Her training had taught her that Americans were ruthless, savage people, but here she was, receiving care from the very same soldiers her country had demonized. The words Yumiko later scribbled in her diary would haunt her for the rest of her life: “Everything I knew was wrong.”

A Disorienting Reality

The prisoners of war, many of whom were women like Yumiko, were sent to American camps after their capture during the fierce battles across the Pacific. Their capture wasn’t just a military defeat; it was a collision of two very different worldviews. For years, the fascist propaganda machine had portrayed the United States as a weak, divided, and morally bankrupt nation. The American military, according to this narrative, was disorganized and incapable of sustaining a long war effort. But Yumiko’s first-hand experience was about to prove this theory fundamentally wrong.

Fort Missoula, Montana, was where Yumiko and other women were detained. The camp was far from what they had expected. It was not a place of confinement filled with starvation and brutality, but one of surprising comfort. There was no barbed wire fence, only a simple chain-link one. The prisoners were housed in large barracks and given ample food. They were given regular opportunities for work release programs, where they could contribute to the local community, and be paid in “script” that could be used to purchase food or goods from the camp exchange.

For Yumiko, this was more than just a physical shock—it was a psychological transformation. The abundance of food, cleanliness, and well-maintained facilities starkly contrasted with the privations they had been led to believe were a universal condition of wartime life. Even their treatment by the American soldiers was at odds with the hatred they had been taught. The soldiers were, to Yumiko’s surprise, kind, respectful, and more than willing to share their food with their prisoners, treating them as people rather than enemies.

The First Taste of American Abundance

The first real jolt to her beliefs came when Yumiko was served her first meal. The American guards didn’t give her the scraps they had been told to expect. They offered her eggs, bacon, toast, and fruit, all things she had only heard about in passing stories before. The fruit, especially, was a shock. As a young child in Japan, she had been told that such luxuries were the reserve of the rich or foreign occupiers. But here, in the heart of wartime America, it was the staple diet.

Yumiko was initially hesitant to touch the food, unsure if it was some trick or a ploy to break her spirit. Yet, as she tasted the eggs and bacon, a strange comfort spread through her. She remembered the rations she had lived on in Japan—meager portions, often shared among family members to make do. The Americans didn’t ration their food in such a way. “This,” she thought, “this is something different.”

The Question of American Strength

Yumiko’s transformation did not happen overnight, but it began with small but undeniable shifts. She couldn’t help but observe the American workers and soldiers with a new perspective. American men, once described as physically weak and incapable, were everywhere. From the guards to the factory workers and farmers, they all seemed robust, healthy, and capable. Their physiques, once derided by Imperial Japan’s propaganda, were clearly not the malnourished bodies that had been painted for her.

In her diary, Yumiko wrote about the shock she felt upon seeing the physical strength of the American men. “They move with power and confidence,” she noted, “the same power that our soldiers are taught to honor.” The more she witnessed, the more she found it impossible to reconcile this reality with the image that had been painted for her by the fascist regime.

She had witnessed American workers cut through logs with a casual ease, perform physical labor that seemed effortless, and walk miles to perform everyday tasks—all without showing any sign of fatigue. She couldn’t ignore the fact that American workers owned their homes, drove their cars, and maintained a standard of living that was far beyond anything she had ever imagined possible.

A Realization of a Larger Truth

For Yumiko, the realization grew deeper as she worked alongside American women. They were not the lazy, disorganized people she had been taught to despise. In fact, many of them worked tirelessly, many holding jobs while their husbands were off at war. These women were mothers, wives, daughters, but also proud, skilled workers who earned their keep and cared for their families.

It became clear to Yumiko that the difference between their nations wasn’t a matter of will or spirit—it was a matter of resources. America had a capacity to produce things that Japan couldn’t even fathom. The food, the materials, the infrastructure—America had created an industrial machine so vast that even a prolonged war couldn’t diminish it. The very hospitals they were treated in were proof of that. They were equipped with supplies that were more plentiful than anything the Japanese medical system had been able to provide in the war’s final years. She saw medical teams perform surgeries using brand new, sterilized tools—things that in Japan were now considered luxuries.

One afternoon, Yumiko saw American soldiers throw away half-eaten chocolate bars. She stared in disbelief. “This is what the Americans do? They waste food?” she thought. But then she realized—this waste wasn’t about disrespect. It was about abundance. The Americans had so much that they could afford to be wasteful.

Reconciliation Through Abundance

By 1946, Yumiko had been exposed to enough of America’s way of life to undergo a profound ideological shift. No longer was she the young woman who had arrived at Fort Missoula with a deep hatred for the American enemy. She had come to understand that America was not the crumbling empire the fascists had painted it to be—it was a nation of strength, both physical and economic, that had been built on a foundation of abundance.

The experience of receiving American medical care, observing American work practices, and living in a society where food was plentiful, people were healthy, and industries were thriving had broken down her previous assumptions. “How could they have done this without fighting among themselves?” she wondered. “How could they have built such a nation from so little?”

Yumiko’s transformation was not an isolated experience. Many of the other Italian and Japanese women imprisoned alongside her would go through similar realizations, as they witnessed firsthand the capabilities of the American people. The very abundance that had been the basis of their initial distrust became the key to their eventual understanding and admiration.

The Lesson Learned

The lessons learned at Fort Missoula would resonate far beyond the confines of the prisoner camp. As Yumiko and her fellow detainees returned to their homes in Japan, they carried with them a wealth of knowledge that would inform Japan’s post-war reconstruction. Many of these women, like Yumiko, would remain in the United States, contributing to the relationship between the two nations in the years that followed.

In the years after the war, Yumiko would often reflect on the day she stood at the entrance of the mess hall and tasted the unimaginable abundance of American life. “Everything I knew was wrong,” she wrote, but in that admission lay the seeds of peace—peace that would eventually transform former enemies into allies.

As Yumiko later said, “The greatest weapon America had wasn’t its army or its air force. It was its ability to feed, to build, and to heal.” What had once seemed impossible to her now made perfect sense. Abundance wasn’t just about having more—it was about creating a society where everyone had enough, where care for life was paramount, and where strength came from the collective power of its people, not just its government.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.