- Homepage

- Uncategorized

- Japanese Kids Followed the Smell of Popcorn — Found U.S. Soldiers Showing Movies in the Village 1945. VD

Japanese Kids Followed the Smell of Popcorn — Found U.S. Soldiers Showing Movies in the Village 1945. VD

Japanese Kids Followed the Smell of Popcorn — Found U.S. Soldiers Showing Movies in the Village 1945

The Scent of Change: A Child’s Encounter with American Generosity

It was August 20th, 1945, five days after Emperor Hirohito’s surrender announcement echoed across Japan. The sun hung low in the sky as 8-year-old Hiroshi Tanaka stood at the edge of his small village near Yokohama. His younger sister, Yumiko, clutched his hand tightly, both of them inhaling deeply as a strange, unfamiliar scent filled the air. The smell was warm, buttery, and impossibly enticing. Neither of them had smelled anything like it in years. It was the smell of popcorn—something they had only heard about but never experienced.

With the war over and Japan’s defeat confirmed, Hiroshi and Yumiko had never expected anything beyond hardship in the days to come. The village, like most of Japan, was in ruins. The streets were silent, the landscape bleak. Yet this strange aroma carried with it something far different—sounds of laughter and music, strange and out of place in a defeated country. It had no place in the Japan they had known for the past six years of war.

Despite the hesitation that gripped him, Hiroshi’s curiosity overcame his fear. He slowly urged Yumiko to follow him as they made their way toward the source of the intoxicating scent. What they found, just a short walk away, defied everything Hiroshi had been taught about the enemy.

In the village square stood several American soldiers, the very demons his teachers had warned him about. They were the monsters who would torture and kill Japanese civilians, or so Hiroshi had been led to believe throughout the war. But instead of bayonets and blood, these soldiers wielded strange machines that puffed white clouds into metal containers. Around them, Japanese children—some of them Hiroshi’s age—gathered eagerly, receiving paper cones filled with the source of the mysterious smell. Popcorn.

And behind them, inconceivably, was a massive white screen with moving pictures flickering to life as darkness settled over the square. The Americans weren’t slaughtering villagers. They were feeding them popcorn and showing them movies.

For Hiroshi, who had been raised on strict imperial propaganda, this moment represented more than just an unexpected kindness from former enemies. It was the first crack in the elaborate facade of lies that had sustained Japan’s wartime society.

The Propaganda of War

For years, the Japanese government had cultivated an image of America as a nation of weak, immoral people, too soft to defend themselves against Japan’s superior warriors. Children were taught to practice with bamboo spears, preparing to die defending their homeland from the Americans, whom they had been told were subhuman monsters. Propaganda films, books, and newspapers painted vivid pictures of Americans as savage beasts who would stop at nothing to destroy Japan.

In schools, children like Hiroshi learned of American atrocities—how captured Japanese soldiers were tortured, mutilated, and desecrated. The Japanese were encouraged to view the American soldier as little more than an animal, a being incapable of compassion or humanity. This indoctrination was reinforced by vivid posters that depicted Americans with fangs and claws, often shown committing unspeakable acts, such as eating Japanese babies or defiling sacred Shinto shrines.

By early 1945, the Japanese public had been led to believe that America was a broken, struggling nation—economically and socially. Reports circulated that American factories were in shambles, that their people lived in poverty, and that their society was on the brink of collapse. The United States, Japan’s leaders insisted, was fighting a war it could never win, a nation incapable of true strength.

But this narrative collapsed the moment Hiroshi and Yumiko followed the scent of popcorn and encountered the Americans in their village.

The Unbelievable Generosity

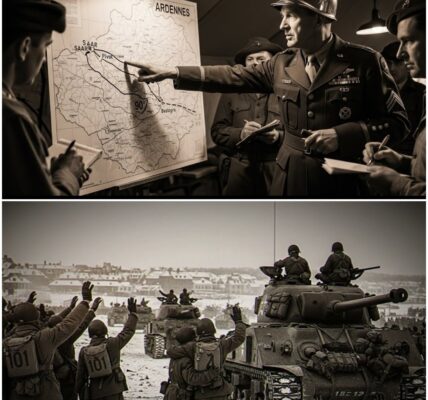

The soldiers, far from the monsters of propaganda, seemed more like ordinary men. Staff Sergeant Michael Donnelly of the 311th Infantry Regiment was operating the popcorn machine with a casual expertise that seemed so normal, it was almost baffling. The machine itself, an electric-powered contraption, gleamed in the fading light of the evening. Donnelly scooped kernels from a burlap sack, and as the popcorn puffed out in clouds of white, it became clear that the soldiers had more than enough.

Donnelly’s actions, offering food to the local children, were no grand gesture. It wasn’t part of a larger strategy to win hearts and minds. It was just something he did because, as he later wrote to his wife back in Pennsylvania, “the kids looked hungry, and we had extra. Seems like the decent thing to do.”

That simple act of sharing food, however, was more than just a kindness—it shattered the carefully constructed myth of American poverty. Hiroshi watched as children, initially too frightened to come close to the soldiers, slowly approached, one by one, drawn by the scent of the popcorn. The soldiers gave them the snack without hesitation, without fear, without malice. They simply gave. They smiled. And they treated the Japanese children with more kindness than Hiroshi had ever seen in his life.

Within an hour, the village square was filled with children, their faces alight with awe and excitement as they watched a Mickey Mouse cartoon on a portable screen, something Hiroshi had never imagined in his wildest dreams. The film, which required no translation, was a universal language of joy. In that moment, the line between enemies blurred, and the propaganda that had shaped Hiroshi’s worldview for so long began to unravel.

The Power of American Abundance

The effects of this encounter were profound, not just for Hiroshi, but for all the villagers. They had been living in a world of deprivation and fear, a world where food was scarce, and every day was a struggle for survival. Many had subsisted on meager rations, often no more than 1,500 calories a day, just enough to keep them alive, but not enough to live fully. By contrast, the Americans had not only food to spare—they had an abundance of it.

What Hiroshi and the villagers witnessed was not just an unexpected kindness from an enemy; it was a glimpse into a world of wealth and generosity that had been beyond their comprehension. The popcorn machine itself was a symbol of American prosperity—an industrial marvel that could produce something as simple as popcorn in quantities far beyond what Japan’s own factories could manage.

It wasn’t just the food. The contrast between the two nations was stark in every way. The American soldiers wore leather boots, proper uniforms, and had access to vast supplies of equipment. In Japan, soldiers had made do with worn-out clothing and makeshift footwear. The American soldiers even had personal jeeps and radios, luxury items Hiroshi had never seen before. He was mesmerized by the sight of American soldiers wearing clean uniforms, while many in his village hadn’t had fresh clothes in years.

And then there was the medicine. When an outbreak of influenza swept through the village, American medical teams arrived with antibiotics, vaccines, and modern medical equipment. The contrast between their advanced care and the crude, often ineffective treatments used in Japan’s wartime hospitals was stark. Captain Robert Westimer, a physician with the Army Medical Corps, set up a temporary clinic, providing care to villagers who had long suffered without proper medical attention.

In that clinic, Hiroshi saw something he had never imagined: health care that was not only abundant, but generous and efficient. It was a sharp reminder of how far Japan had fallen behind in terms of resources, even as its leaders had promised victory over the Americans.

A New Reality

As the occupation continued, the American soldiers became more than just occupiers. They became a part of the village’s life. They organized baseball games with the children, handed out chewing gum, and shared small gifts with the villagers. Hiroshi, Yumiko, and the others who had once feared these soldiers began to see them not as monsters, but as human beings—people who had fought for their country, yes, but who also had the compassion to share with others.

The American soldiers’ casual generosity, something Hiroshi could never have imagined, forced him to reconsider everything he had been taught. The reality of American strength and prosperity had been hidden from him for so long, but now it was undeniable. The popcorn, the movies, the shoes, the medicine—everything they had once believed about the Americans was called into question.

Reconstructing Japan’s Future

By the end of 1945, as the occupation continued, the psychological transformation in Hiroshi’s village and others like it was profound. The American troops, originally seen as the brutal enemy, were now perceived as a force for healing and progress. The ideological walls that had been built up during the war began to crumble, replaced by a new understanding of what America was—and what Japan could become if it embraced change.

For Hiroshi and his peers, this transformation was just the beginning. The lessons learned from the American occupation—lessons about industry, abundance, generosity, and the power of a society based on equality—would shape their futures. Hiroshi eventually went on to study engineering at Tokyo University and joined Toyota Motor Corporation, helping the company embrace American manufacturing techniques that would contribute to Japan’s rise as an economic powerhouse.

But the most enduring impact of the American occupation was on the collective psyche of Japan. For years, the Japanese people had been taught to fear and hate their enemies, but through simple acts of kindness, the Americans showed them a different way. A way that would not only lead to a new economic future for Japan, but also to a new relationship between former enemies, one rooted in respect, cooperation, and shared prosperity.

For Hiroshi Tanaka, the smell of popcorn was more than just a fleeting moment of childhood wonder. It was the moment that shattered the myths of war, the moment that opened his eyes to a new reality—one where abundance and generosity were not just the result of military might, but of a society built on the principles of freedom and equality.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.