“It’s Too Greasy!” German Women POWs Laughed at American Fried Chicken, Until They Ate It_NUp

“It’s Too Greasy!” German Women POWs Laughed at American Fried Chicken, Until They Ate It

The mess hall doors swung open on a suffocating July afternoon in 1945, and the smell hit them first.

Hot oil. Seasoned flour. Pepper and salt carried on the heavy Texas air.

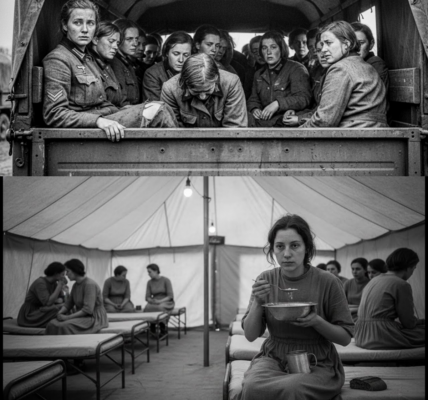

Behind the barbed wire of Camp Swift, a U.S. prisoner-of-war camp outside Bastrop, several dozen captured German women filed inside with the stiff posture of people who expected disappointment at best—and humiliation at worst. They were Luftwaffe auxiliaries, nurses, clerks, radio operators. Educated. Disciplined. Certain of who they were, and who their enemies were supposed to be.

What they saw stopped them cold.

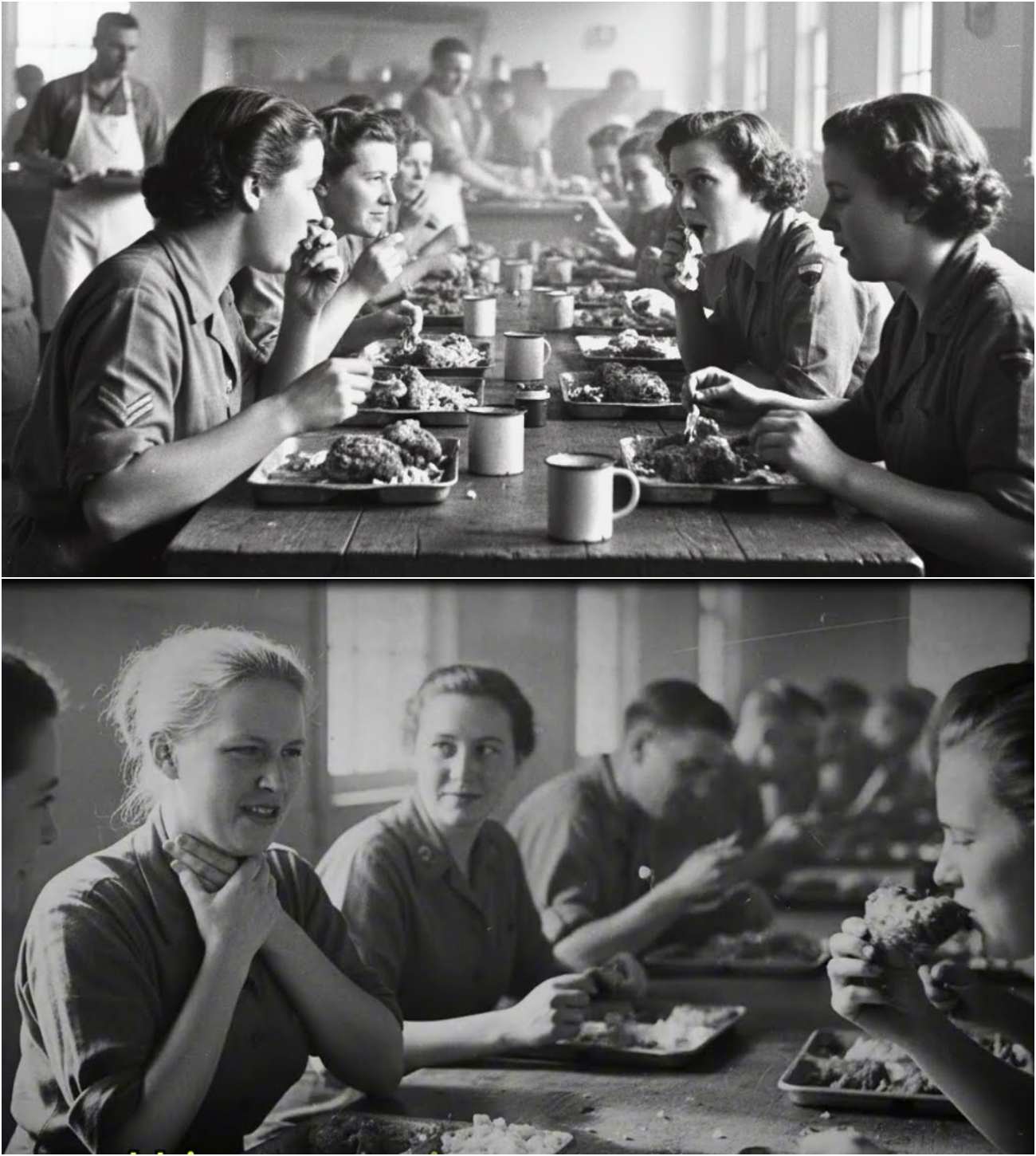

Long metal tables were piled high with golden-brown fried chicken, mounds of creamy mashed potatoes drowned in gravy, buttered vegetables, and soft white rolls stacked like clouds. The food glistened under harsh overhead lights with an abundance that felt almost obscene to women who had survived collapsing supply lines and near-starvation in the final months of the war.

For a moment, no one spoke.

Then the laughter started.

“THIS IS AMERICAN COOKING?”

Hildegard Krauss, a 31-year-old communications officer from Munich, lifted a chicken leg between two fingers as if it were contaminated. Grease dotted her fingertips. She held it at arm’s length, studying the thick, golden crust like a failed laboratory experiment.

“Was ist das?” she muttered.

What is this?

The women around her leaned in, whispering and smirking.

“It looks like they rolled it in sand,” said Greta Reinhardt, a former schoolteacher from Hamburg.

“And then drowned it in fat.”

Nervous laughter rippled down the line. For women raised on roasted poultry, pan-schnitzel, and carefully balanced European flavors, this looked crude. Excessive. Everything Nazi propaganda had promised American culture would be.

Hildegard set the chicken back on her plate with dramatic disgust.

“Das ist fettig,” she announced.

“It’s too greasy.”

Several women nodded, pushing their plates away like judges dismissing a failed contestant.

THE AMERICAN WHO TOOK IT PERSONALLY

From the far end of the mess hall, Corporal James Whitaker watched.

He was 23, sunburned, and from rural Alabama. He’d been assigned to kitchen duty—hardly glamorous work for a soldier who’d crossed the Atlantic to fight a war. The fried chicken recipe was his grandmother’s, perfected through decades of Sunday dinners and church picnics.

He’d seen German POWs reject corn as animal feed, save white bread for dessert because it tasted like cake, and complain that American coffee was “wrong.”

But this—this hit different.

That chicken was art.

“You might wanna try it before you judge it,” he called out, his Southern drawl cutting through the German chatter.

The women ignored him. Or pretended not to understand.

One young blonde woman—barely twenty—made an exaggerated gagging motion, drawing fresh laughter.

Whitaker clenched his jaw and turned back to the serving line.

HUNGER IS STRONGER THAN IDEOLOGY

But hunger doesn’t care about pride.

Hildegard noticed something unsettling. At nearby tables, male German POWs—men who had been at Camp Swift longer—were eating the same chicken with unmistakable enthusiasm. Fingers shiny with grease. Faces relaxed. Happy.

One former Luftwaffe captain was already on his second piece.

He caught Hildegard staring and grinned.

“Versuch es!” he called.

Try it.

She looked back down at her plate. Steam still rose from the torn crust. The smell—salty, peppery, rich—slipped past her defenses and made her mouth water despite herself.

“It’s probably terrible,” she said loudly, as much for her own benefit as the others.

She took a bite.

THE SOUND OF A BELIEF SHATTERING

The crust shattered between her teeth.

A crisp, audible crack—followed by a rush of flavor she had not been prepared for. Salt. Pepper. Something warm and herbal. Then the chicken itself: impossibly tender, so juicy it nearly melted.

Hildegard froze mid-chew.

Greta leaned in. “Well?”

Hildegard swallowed. Looked down at the bite mark exposing glistening white meat.

She thought of her mother’s careful Sunday roasts. Of everything she’d been taught about refinement and superiority.

Then she took another bite.

“It’s…” She hesitated, the word feeling like a betrayal.

“It’s extraordinary.”

The table went silent.

Greta grabbed her own chicken and bit down. The same transformation crossed her face—skepticism giving way to shock, then pleasure.

Within minutes, the laughter in that section of the mess hall changed completely. Mockery dissolved into murmurs of appreciation. Women who had held their food at arm’s length were now hunched over plates, gnawing bones with unladylike focus.

The blonde woman who had gagged earlier was licking her fingers and eyeing her neighbor’s plate.

Whitaker couldn’t stop smiling.

“There’s more if you want seconds.”

Hands shot up instantly.

MORE THAN JUST A MEAL

As the women lined up for seconds—then thirds—something subtle but profound happened.

This wasn’t just about fried chicken.

This was about certainty cracking.

Hildegard sat back down with a full plate, staring at it like it was dangerous. Everything she had been taught said this moment shouldn’t exist. Prisoners weren’t supposed to be well-fed. Enemies weren’t supposed to cook like this. Americans weren’t supposed to care.

Yet here she was, eagerly reaching for another piece of chicken made by a man whose grandmother she would never meet.

She noticed the camp commander, Captain Robert Charara, watching from the doorway. When the women had arrived weeks earlier, he’d promised dignity, respect, and full meals.

At the time, it had sounded like a lie.

Now it tasted like truth.

WHEN FRIED CHICKEN BECAME AN EVENT

In the weeks that followed, fried chicken became legendary at Camp Swift.

When it appeared on the menu, the German women didn’t hesitate. They debated which batch was best. They asked questions. They learned words in English just to talk about spices.

Greta translated eagerly.

“She wants to know what you put in the coating,” she told Whitaker one afternoon.

He rattled off ingredients—paprika, black pepper, garlic powder—and mentioned a “family secret” he refused to reveal.

The women listened like scholars.

Then came other revelations.

Corn on the cob wasn’t animal feed—it was sweet.

White bread wasn’t inferior—it soaked up gravy beautifully.

Cornbread, once dismissed as livestock food, became a favorite.

One camp rumor claimed the women asked for it every day.

WHAT THEY TOOK HOME

When Hildegard was repatriated in early 1946, she carried almost nothing.

Germany was in ruins. Space was precious.

But folded carefully in her coat pocket was a handwritten recipe—Southern fried chicken, translated into German, smudged with grease from multiple test batches in the camp kitchen.

She also carried something heavier.

Memories that didn’t fit the old story.

American guards who showed respect.

A mess hall where enemies ate the same food.

The moment she realized she might have been wrong about everything.

Years later, in a rebuilt Munich apartment, she served fried chicken to her family. Her children laughed at how strange it was.

“Where did you learn this?” they asked.

She paused before answering.

“In a prison camp in Texas,” she said. “Where I learned that kindness doesn’t belong to one country.”

THE BATTLE THAT FRIED CHICKEN WON

Hildegard would later say it wasn’t really about the food.

It was about the shock of discovering that an enemy could be generous. That an “inferior” culture could create something beautiful. That propaganda could crumble—not under bombs, but under breadcrumbs and hot oil.

A piece of fried chicken didn’t end the war.

But it won a quiet, permanent victory over hatred.

And sometimes, that’s the kind that lasts the longest.