Italian POWs in California Thought They Were Being Punished When Given This Job

At 9:47 on the morning of September 14th, 1943, Private Jeppe Tosselli stood in the processing yard at Fort McDow on Angel Island, San Francisco Bay, watching American guards hand out work assignments to the line of Italian prisoners. 26 years old, trained as a stone worker in Tuscanyany, captured at Bizerte 3 months earlier. Jeppe had spent the voyage from North Africa preparing himself for what came next. Hard labor, rock quaries, maybe, or digging ditches in the California heat.

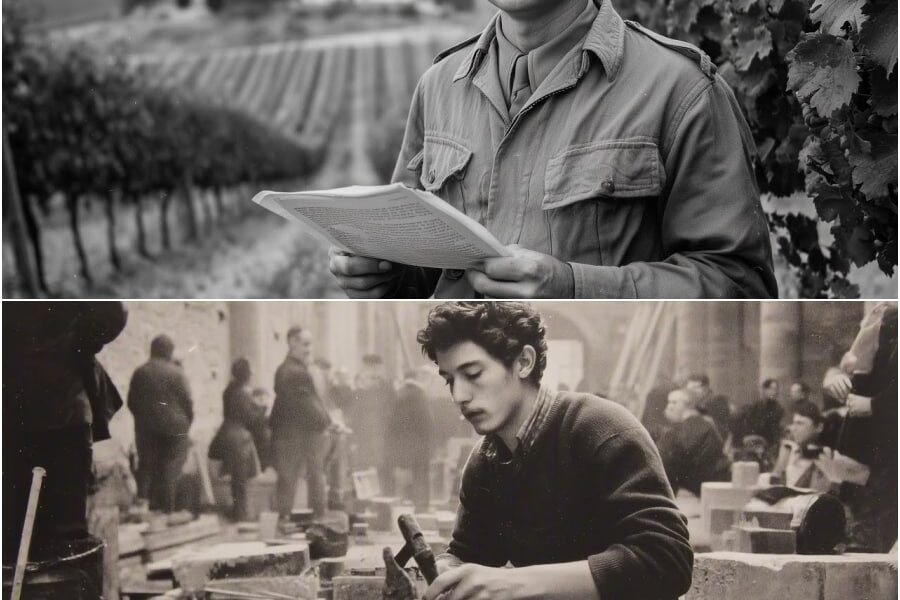

The other prisoners had told him Americans treated PS better than Germans did. But Jeppe knew what captivity meant. Punishment work. Manual labor designed to break your spirit before breaking your body. The guard called his name. Joseeppe stepped forward. The guard handed him a slip of paper with an address in Napa Valley and three words written in English. Vineyard work detail. Jeppe read the paper twice. He turned to the prisoner next to him, a corporal from Bolognia named Carlo Mancini.

They’re sending us to work in vineyards, Jeppe said. Like farmers, like peasants. Carlo stared at his own assignment slip. His face went red. This is the punishment, Carlos said. They’re mocking us, putting skilled men in fields like animals. Joseeppe had worked stone since he was 14, cathedral restoration in Florence, marble cutting in Kurara. His hands were made for precision work, for craft. Now Americans wanted him to pick grapes. He folded the paper and put it in his pocket.

At least it wasn’t a firing squad. What Jeppe didn’t know was that within 18 months he would own a percentage of that same vineyard. That Carlo would be managing a restaurant in San Francisco’s North Beach where Italian-American families waited 2 hours for tables. That the punishment Jeppe feared would become the opportunity that saved his life and made him wealthy. The Italian prisoners had been arriving in California since early 1943. Most came from North Africa campaigns. Seasoned soldiers captured at Tunis, Bazerte, Sicily.

The Americans shipped them across the Atlantic, then by rail across the United States to processing centers on the West Coast. Fort McDow received hundreds of Italian PS every week. The prisoners expected what prisoners always expected. Barbed wire, guard towers, hard labor assignments designed to support the American war effort without violating Geneva Convention rules about P treatment. Instead, the Americans sent them to vineyards, farms, dairies, restaurants, and food processing facilities across Northern California. The assignments confused the Italians.

Some thought it was temporary, that the real work would come later. Others thought the Americans were conducting some kind of psychological test, seeing how Italian prisoners responded to humiliation before assigning them to actual labor. Jeppe arrived at the Napa vineyard on September 17th, 1943. The vineyard covered 200 acres of valley floor planted with Cabernet Sovenon and Zinfendel grapes. The owner was a man named William Croft. 63 years old, third generation California wine maker. Croft met Jeppe and 11 other Italian prisoners at the vineyard entrance.

He had a truck waiting to drive them to the worker’s quarters. Jeppe expected barracks. He got a converted farmhouse with individual rooms, running water, and a kitchen. The guards told them they would work 6 days per week, 8 hours per day. Pay was 80 cents per day in camp credits that could be used to purchase extra food, cigarettes, writing materials, and personal items from the camp commissary. Sundays were free. Joseeppe listened to this explanation and waited for the other shoe to drop.

The hidden punishment, the catch that would make sense of why Americans were treating prisoners like hired workers instead of captives. The work began the next morning. Croft’s vineyard manager, a man named Thomas Chen, whose family had owned farms in the valley since the 1880s, gathered the prisoners at dawn, and explained the job. The grapes were ready for harvest. The prisoners would work in teams of two, moving through rows with cutting shears and collection bins. Cut the grape clusters at the stem.

Place them gently in the bins. Don’t damage the fruit. When a bin was full, carry it to the collection truck at the end of the row. Jeppe had never worked a vineyard in his life. Stone was his craft, not agriculture, but he understood physical labor, understood the rhythm of repetitive work. He partnered with Carlo, and they started down their assigned row. The morning was cool. The grapes hung heavy on the vines. Jeppe used the shears carefully, cutting each cluster at the stem without crushing the fruit.

The work was methodical, almost meditative. No guards shouting, no quota to meet, just the quiet sound of shears cutting stems and grapes dropping into bins. By noon, Jeppe had filled eight bins. His back hurt. His hands were cramped from gripping the shears, but the pain was different from stonework. lighter somehow less violent. Thomas Chen came through the rows at lunchtime with sandwiches and water. The prisoners sat in the shade of the vines and ate. Jeppe expected prison rations, but the sandwiches were thick with meat and cheese, the bread fresh.

Carlo ate his sandwich without speaking, then turned to Jeppe. This is very strange, Carlo said. I don’t understand what they want from us. Josephe didn’t understand either. The work was real. The grapes would be processed into wine that would be sold for profit. The Americans were using Italian labor to support a commercial enterprise, but they were paying for it. Treating the prisoners like employees, not captives. Joseeppe had spent 3 months in a British P camp in North Africa before transferred to American custody.

The British had treated him correctly according to Geneva Convention standards, but there had been no ambiguity about the relationship. Guards and prisoners, captives and captives, clear lines of authority and submission. Here in Napa Valley, the lines were blurred. The guards were present but distant. They drove the prisoners to work each morning and picked them up each evening. But during work hours, they mostly sat in their vehicles and smoked cigarettes. Thomas Chen gave orders, but he gave them the way a foreman gives orders to hired workers, not the way a captor gives orders to prisoners.

He explained tasks. He demonstrated techniques. He asked questions about whether the prisoners understood the instructions. That first week, Jeppe worked the vineyard rose and tried to understand the American logic. Maybe this was efficiency. Maybe Americans had calculated that treating prisoners well produced better work output than treating them harshly. Or maybe Americans just needed workers and didn’t care whether those workers were free men or prisoners of war. On Sunday, September 26th, Jeppe and Carlo took the transport truck back to Fort McDow.

They attended chapel services, then visited the camp commissary. Josephe spent 40 cents of his week’s pay on cigarettes and writing paper. He wrote a letter to his mother in Florence. He told her he was safe, working in a vineyard, that the Americans were treating him well. He did not tell her that he was confused, that he didn’t understand why captivity felt less like punishment than some jobs he’d had as a free man in Italy. The change began in October.

The grape harvest was finishing. Jeppe assumed the Americans would reassign the prisoners to different work. Instead, William Croft asked Thomas Chen to select six prisoners with farming or agricultural experience for permanent assignment to the vineyard. Chen interviewed the 12 Italian prisoners individually. He asked about their backgrounds, their skills, their experience with agriculture. Jeppe told Chen he was a stone worker, that he had no farming experience. Chen wrote this down, then asked if Jeppe was interested in learning.

Jeppe said yes, because what else could he say? 2 days later, Chen announced the selections. Jeppe was one of the six. He would remain at the Napa Vineyard permanently, learning American viticulture techniques and assisting with winter maintenance and spring planting operations. Carlo was not selected. He was being sent to a restaurant in San Francisco working as kitchen staff. Carlo was furious. Kitchen work, he said to Jeppe the night before transfer. Like I’m a servant. Like I’m nobody.

The next morning, Carlo left on the truck with the other five prisoners. Josephe never saw him again during the war. Years later, Jeppe would learn that Carlo had become the head chef at that same San Francisco restaurant, that he’d married the owner’s daughter, that he’d eventually bought the restaurant and turned it into one of the most successful Italian establishments in North Beach. But in October 1943, Carlo left angry, convinced he was being punished. Jeppe stayed at the vineyard.

The work changed after the harvest. Now it was winter maintenance, pruning vines, repairing trelluses, checking irrigation systems. Thomas Chen taught Josephe how to identify which canes to cut and which to leave, how to maintain the vine structure for optimal fruit production in the next growing season. The work required precision, judgment, attention to detail. Josephe found himself enjoying it. The vines had logic. Like stone had logic. You had to understand the material, respect its nature, work with it rather than against it.

In November, Josephe met Robert Mondavi. Mundavi was 30 years old, working in his family’s winery in Loi. He’d come to Croft’s vineyard to discuss a potential wine purchase. Croft introduced Jeppe as one of his workers. didn’t mention that Jeppe was a prisoner of war. Mondavi spoke some Italian, learned from his immigrant parents. He asked Jeppe about his background. Joseeppe told him about Florence, about stonework, about the cathedral restoration projects. Mandavi listened, then said something that confused Jeppe.

You’re lucky you ended up here. Mandavi said, “After the war, California wine industry is going to explode. If you know what you’re doing with grapes, you’ll never be poor. Jeppe didn’t know what to say to that. He was a prisoner of war working in a vineyard because he’d been captured by Americans and assigned this work detail. Luck didn’t seem like the right word for it. But Mandavi was serious. He explained that California wine production had been devastated by prohibition, that the industry was just starting to recover.

Most American wine was still lowquality, mass- prodduced for quantity rather than craft. But that was changing. Americans were developing more sophisticated tastes. They wanted better wine. They wanted European style quality. And there weren’t enough skilled workers in California who knew how to produce it. Italians know wine. Mandavi said, “You grow up with it. You understand fermentation, aging, blending. That knowledge is valuable here. After the war, if you want to stay, there will be opportunities. Juspe thanked Mandavi for the conversation, but he didn’t take it seriously.

He was a prisoner of war. After the war, he would return to Italy. He would resume his stonework. California was temporary. A strange interlude in his life that would end when the fighting stopped. In December 1943, Joseph’s understanding began to change. A local Italian-American family, the Benedetis, invited several prisoners from the vineyard to Sunday dinner at their home in Napa. The Benedetis had immigrated from Piedmont in 1912. They owned a small restaurant in town. They wanted to meet the Italian prisoners, hear news from home, share a meal with men who spoke their language and understood their culture.

Joseeppe accepted the invitation along with three other prisoners. The guards approved it. The Benedetes picked them up at the vineyard on Sunday afternoon and drove them to a house on Third Street. Inside, the smell of cooking filled every room. pasta, tomato sauce, roasted meat, fresh bread. Juspe hadn’t smelled food like that since leaving Italy. The Benadetes treated the prisoners not as enemies or captives, but as guests. The father, Antonio, shook Josephe’s hand and welcomed him in Italian.

The mother, Mariah, hugged him and said he looked too thin, that he needed to eat more. There were three children, two daughters in their 20s, both working at the restaurant, and a son, 17 years old, who would be drafted soon, and sent to fight in the Pacific. They sat at a long table in the dining room. Antonio opened a bottle of wine from his own small vineyard behind the house. He poured glasses for everyone, including the prisoners.

Joseeppe sipped the wine and felt something break inside him. Not sadness exactly, but a kind of recognition. The wine tasted like home. The food tasted like home. The conversation, the laughter, the warmth of this family’s kitchen. All of it reminded him of everything he’d lost when he put on a uniform and went to war. Antonio asked Josephe about his family in Florence. Josephe told him about his mother, his two sisters, his younger brother who was serving somewhere in the Italian army.

Last letter received in June with no words since. Antonio nodded. He understood. His own cousins were still in Italy fighting for Mussolini, fighting against Americans. The war had split families, split loyalties, created impossible situations where good people found themselves on opposite sides. But here in this dining room in Napa, California, those divisions didn’t seem to matter. Antonio poured more wine. Maria brought out another course. The daughters asked Jeppe about Florence, about the cathedral, about whether the Germans had damaged the city.

The son asked Jeppe about combat, about what it was like to be captured, about whether American soldiers were really as tough as the propaganda said. Joseeppe answered their questions honestly. He told them about Bizerte, about the artillery barrage that killed most of his company, about the moment when he threw down his rifle and raised his hands because continuing to fight meant dying for no purpose. He told them about the British P camp, about the voyage to America, about his confusion when he arrived in California and was assigned to work in a vineyard instead of a quarry.

Antonio laughed at that. Americans don’t understand punishment the way Europeans do, Antonio said. They think work is its own reward. They think giving a man a job is the same as giving him dignity. Is that wrong? Joseeppe asked. Not wrong, Antonio said just different. In Italy, we understand that some work is noble and some work is degrading. Americans think all work is noble if you do it well. They don’t care about class or status. They care about results.

Joseeppe thought about that. He thought about Thomas Chen teaching him how to prune vines, treating him like an apprentice rather than a prisoner. He thought about William Croft paying him 80 cents per day, the same rate Croft paid his free workers. He thought about Robert Mandavi telling him there would be opportunities after the war. As if Joseph’s status as an enemy prisoner didn’t matter compared to his knowledge of wine. Maybe Antonio was right. Maybe Americans did think differently about work, about dignity, about what it meant to be a man.

And maybe that difference explained why Jeppe’s punishment felt less like captivity and more like the best job he’d ever had. The dinner lasted 4 hours. When it ended, Antonio insisted Juspe take a bottle of wine back to the vineyard. “For you and the other men,” Antonio said. “So you remember there’s still beauty in the world.” Jeppe took the wine. That night he shared it with the other prisoners in the farmhouse. They passed the bottle around. each man taking a small drink.

Nobody spoke much. There was nothing to say. The wine said everything. In January 1944, Thomas Chen started paying Jeppe more. Not directly because Pay was fixed by Geneva Convention rules, but Chen found ways. Extra food from the vineyard owner’s personal stock. Better cigarettes from town. small tools and supplies that made the work easier. Chen called it skill recognition. He said good workers deserved good treatment, that it was just good business. Jeppe began to understand something important. The Americans weren’t being generous out of moral principle.

They were being pragmatic. They needed workers. They had prisoners. The prisoners had skills. Using those skills efficiently required treating the prisoners well enough that they would work productively. It was calculation, not charity. But the result was the same. Josephe ate well. He slept in a comfortable bed. He learned valuable skills. He saved his 80 cents per day in camp credits. Accumulated over $400 by March 1944. In April 1944, Italy officially surrendered and switched sides. Italian prisoners of war in American custody were redesated as co-belligerants, a legal status that meant they were no longer enemy prisoners, but not quite allies either.

The practical effect was minimal. Jeppe still worked at the vineyard. He still lived in the farmhouse. He still earned 80 cents per day, but the psychological effect was significant. He was no longer a captive. He was a worker. William Croft spoke to Jeppe in May. Croft wanted to discuss the future. The vineyard was expanding. Croft had purchased an adjacent 200 acres and planned to plant new varietals, Merllo and Pon Noir. The expansion would require experienced workers, people who understood viticulture, people who could be trusted to manage sections of the vineyard without constant supervision.

Croft offered Juicipe a permanent position after the war, not as a prisoner worker, but as a vineyard manager. Salary would be $150 per month, plus housing, plus a percentage of profits from any section Jeppe managed directly. Croft said Jeppe had proven himself capable. Croft said he’d rather hire someone he knew and trusted than take chances with unknown workers. Josephe asked if this offer was legal. Croft said he’d spoken with military authorities. Co-elligerent Italians were allowed to remain in the United States after the war if they had employment sponsors and could demonstrate economic self-sufficiency.

Croft would sponsor Jeppe. Jeppe asked for time to think about it. Croft gave him until June. Jeppe spent that month wrestling with the decision. Return to Italy or stay in California, home or opportunity. Everything he knew or everything he could become. He wrote to his mother. The letter took two months to reach Florence. His mother’s response took another two months to come back. When it arrived in August, Josephe opened it with shaking hands. His mother’s letter was four pages long.

She described Florence under German occupation. Food shortages, Allied bombing, her house damaged but still standing. Joseeppe’s brother was dead, killed in Russia in 1943. One of his sisters had married and moved to Milan. The other sister was still in Florence, working in a factory that made uniforms for German soldiers. His mother’s final paragraph was blunt. There is nothing for you here. The city is ruins. The work is gone. Your skills will not be needed for years, maybe decades.

If you have opportunity in America, take it. Build a life. Send money when you can, but don’t come back to this. Jeppe read the letter three times. Then he walked to William Croft’s house and accepted the job offer. The war in Europe ended in May 1945. The war in the Pacific ended in August. Joseeppe was officially discharged from Italian military service in September. He signed a contract with William Croft in October. He became a legal resident of the United States in November.

By December 1945, Josephe Toelli was no longer a prisoner of war. He was a vineyard manager in Napa Valley, California, earning $150 per month, plus a percentage of profits from 200 acres of premium wine grapes. Joseeppe worked for Croft for 5 years. He learned American business practices. He learned how to manage workers, negotiate with buyers, market premium wine to restaurants and hotels. In 1950, Croft offered Jeppe a partnership, 20% ownership of the vineyard in exchange for Jeppe’s continued management and a $20,000 investment.

Jeppe had saved $32,000 over 6 years of work. He accepted the partnership. By 1960, Croft’s vineyard was producing some of the highest quality Cabernet Sovenon in California. Robert Mondavi, who Jeppe had met in 1943, now ran his family’s winery and regularly purchased grapes from Croft. Mondavi remembered Jeppe from that first meeting. I told you California wine was going to explode, Mondavi said. I told you if you knew what you were doing with grapes, you’d never be poor.

Jeppe remembered in 1965, Joseph’s share of the vineyard’s annual profit was $68,000, more money than his father had earned in an entire lifetime of stonework in Florence. Joseeppe never returned to Italy. He sent money to his mother every month until she died in 1968. He sponsored his surviving sister’s immigration to California in 1952. She settled in San Francisco, married an Italian-American man who owned a construction business. Jueppi attended the wedding and met several other former Italian PWs who had stayed in California after the war.

Some worked in restaurants. Some worked in construction. Some owned their own businesses. All of them told similar stories. They had arrived expecting punishment. They had received opportunity instead. Jeppe met Carlo again in 1958. Carlo was running his restaurant in North Beach, three locations now, making a fortune. Carlo laughed when he saw Jeppe. Remember when we thought working in vineyards and kitchens was punishment? Carlo said, “Remember when we thought Americans were mocking us?” Jeppe remembered. He’d spent 15 years trying to understand the American logic.

Americans didn’t think about work the way Europeans did. They didn’t think about class or status or dignity the same way. They thought about results. They thought about efficiency. They thought about whether a man could do a job well, not whether the job was appropriate for that man’s background or training. It was a strange way of thinking, but it had saved Josephe’s life. He had come to California expecting degradation and found dignity instead. He had come expecting punishment and found prosperity.

Jueppi married in 1961. Her name was Anna, second generation Italian American, family from Genoa. They had three children. Jeppe taught all of them about wine, about viticulture, about the business he’d built from nothing. In 1975, Jeppe purchased William Croft’s remaining 80% of the vineyard. Croft was 95 years old, ready to retire. He sold to Jeppe for fair market value, plus a clause in the contract that the vineyard would keep Croft’s name. Jeppe agreed. Croft had given him a chance when he was a prisoner of war with no prospects and no future.

Keeping the name was the least Jeppe could do. By 1980, Jeppe owned 400 acres of premium vineyards in Napa Valley. His wine sold internationally. Wine critics ranked his Cabernet Svenon among the finest in California. Jeppe employed 40 workers, managed three separate production facilities, and served on the board of directors for the California Wine Institute. He was 63 years old. He had started as a prisoner of war, assigned to punishment work in a vineyard. He had become one of the most successful wine producers in America.

Joseeppe’s story was not unique. Records show that approximately 5,000 Italian PSWs worked in California agriculture, restaurants, and food processing during the war. Hundreds stayed after the war ended. Many became successful business owners. Some became millionaires. The exact numbers are difficult to verify because many former PWs didn’t publicize their backgrounds. They simply integrated into Italian-American communities and built lives. But the pattern is clear. Italian prisoners arrived in California expecting hard labor and degradation. They received jobs that utilized their skills and treated them like valuable workers.

The disconnect between expectation and reality confused them initially. Many thought it was a trick, a psychological game the Americans were playing. They waited for the other shoe to drop, for the real punishment to begin. It never did. The punishment was the opportunity. The degradation was dignity. The captivity was freedom. Juspe Toelli died on March 18th, 1994. He was 77 years old. His obituary in the Napa Valley Register ran four columns and included tributes from Robert Mondavi, from the governor of California, and from the Italian consul in San Francisco.

The obituary mentioned his service in the Italian army, his capture at Bazerte, his arrival in California as a prisoner of war, but it focused primarily on his achievements. 400 acres of premium vineyard, three children who all worked in the wine industry, 43 years of contributions to California viticulture. Jeppe’s children donated his personal papers to the Napa Valley Wine Library in 1995. The collection includes letters Juspe wrote to his mother during the war describing his confusion about American treatment of prisoners.

The collection includes the contract William Croft offered Josephe in 1945. The collection includes photographs of Jeppe working the vineyard in the 1940s wearing prison work clothes because he couldn’t afford civilian clothing yet. The documents tell a story that thousands of Italian prisoners experienced in California during World War II. They tell a story about expectations versus reality. About how punishment sometimes looks like opportunity if you’re willing to see it. About how the worst thing that ever happened to you can become the best thing if circumstances align correctly.

Jeppe never forgave the war. He never romanticized his capture or his imprisonment. He understood that he’d been lucky. Lucky to be captured by Americans instead of Russians. Lucky to be sent to California instead of Texas or Arizona. Lucky to be assigned to a vineyard instead of a mine or a factory. Luck, not virtue. Circumstance, not heroism. But he also understood something else. Americans had given him a choice. Even if they didn’t realize it, they put him in a position where he could succeed or fail based on his own decisions, his own work, his own willingness to adapt.

They treated him like a man capable of making his own future rather than a prisoner whose future was determined by others. That treatment, that assumption of capability and agency, had changed everything. Josephe had arrived in California expecting to be broken. Instead, he’d been given tools to build. The Americans had called it punishment. Joseeppe had called it confusion. History would call it one of the strangest and most successful prisoner of war programs in American military history.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.