“It Burns When You Touch It” – German Woman POW’s Hidden Injury Shocked the American Soldier. NU.

“It Burns When You Touch It” – German Woman POW’s Hidden Injury Shocked the American Soldier

April 1945. A muddy field aid station somewhere near the Rhine.

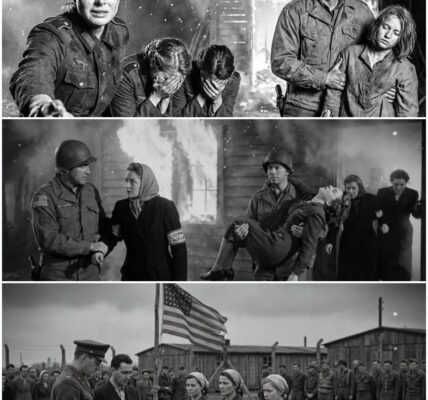

The tent sagged under the weight of rain and exhaustion. Outside, trucks growled and shouted orders cut through the damp morning. Inside, it was chaos—cots jammed together, men groaning, surgeons barking for plasma, the thick, sour smell of sulfa powder, blood, and the sweet rot of gangrene.

Two medics from the US 45th Infantry Division pushed through the crush carrying a stretcher. On it lay a girl in a Luftwaffe helper’s uniform, soaked in blood and mud, her face the color of ash.

“Only survivor from that flak battery on the ridge,” one medic muttered. “They overran ’em at dawn.”

Corporal Daniel “Danny” Goldstein, twenty-two, from Philadelphia, stepped toward them with his clipboard. To the staff he was just another triage nurse, skinny and sleepless, with permanent smudges under his eyes. To the paperwork, he was Jewish, born in Berlin, family fled in 1938. To the wounded, he was the man who kept showing up with morphine and water when everyone else was too busy.

He knelt beside the stretcher.

The girl flinched at his touch, eyes wide with the pale, glassy terror he’d seen too many times in the last month.

He heard the accent the moment she whispered, “Bitte…nicht. Bitte töten Sie mich nicht. Please don’t kill me.”

Danny switched to German, the soft Berlin vowels his mother still used in the kitchen.

“Hey,” he said quietly, “ich bin Sanitäter. I’m a medic. Ich helfe. I’m here to help.”

She stared at him, not quite believing.

Her name, he learned as he checked her dog tag, was Grier Elsa Becker. Twenty years old. Munich.

He cut away her torn jacket with scissors, hands steady, voice calm. “I’m just going to look, okay?”

Under the shredded uniform, someone had tied a crude bandage around her lower back and hip. It was soaked through, stiff with dried blood. When he began peeling it back, the smell hit him first.

He’d seen a thousand wounds by then. He’d never seen one like this on someone still conscious.

A jagged shrapnel tear carved across her lower back and hip, the flesh swollen, black and green at the edges, streaked red up toward the kidneys. It had been there for days. Maggots crawled in pale clumps at the deepest part, doing the awful, necessary work nature had invented them for.

Elsa turned her head away, ashamed, bracing for the disgust she expected in his eyes.

Instead, Danny swore softly in Italian under his breath, then raised his voice in English.

“Morphine. Plasma. Get Miller. Now.”

The head surgeon, Major Frank Miller from Chicago, arrived still wearing someone else’s blood on his apron. He took one look, lips thinning.

“Goldstein, she’s septic. We’re overloaded. She’s enemy. Prioritize our boys.”

Danny stood up, meeting his eyes.

“Sir, with respect, she’s a twenty-year-old girl who’s been hiding this for God knows how long. She’s conscious. She’s fighting. We can save her.”

Miller hesitated. The tent was full of American uniforms, American dog tags, American moans. The pile of charts waiting for surgery was already too high.

Danny didn’t wait for his decision. He slid a needle into Elsa’s arm, started the IV himself, pushed morphine, his German running softly in her ear as the drug pulled the pain down.

“Du wirst nicht sterben. Not today. You’re not dying today.”

For four hours, he and Miller worked in grim silence.

They cut away sloughing flesh, washed the wound with saline and sulfa, chased infection back inch by inch. They picked out fourteen pieces of shrapnel scavenged from metal that had tried to end her life. They debrided until healthy tissue bled clean red instead of the gray ooze of rot. At one point Miller muttered, almost to himself, “She should’ve been dead two days ago.”

Elsa drifted in and out, sometimes moaning, sometimes whispering feverish nonsense. Once, her eyes snapped open and she clawed at the stretcher, gasping, “Es brennt, es brennt—it burns, it burns.”

Danny’s gloved hand rested on her shoulder, the only place untouched.

“I know,” he said. “We’re putting the fire out.”

By the time they finished, it was two in the morning. She had lost half the muscle of her left hip and glute, and a wedge of bone besides. The maggots were gone. The black necrosis was gone. What remained was raw, ugly, clean.

She would live.

Danny sat down on a wooden crate beside her cot. He changed her dressings when they bled through. He dabbed water on her lips. He shooed orderlies away who wanted to move on. At some point he fell asleep in the chair, boots still muddy, chin on his chest.

She woke at sunrise to the pale light of a new day sliding under the edge of the tent. For a moment she didn’t know where she was. Then the pain in her back came flooding in—different now, not the deep, eating burn of infection, but a sharper, cleaner hurt.

She turned her head. Danny was there, slumped in the chair, snoring lightly, dog tags glinting against his T-shirt. His sleeves were rolled up. Dried blood darkened the hair on his forearms.

Elsa swallowed. Her throat felt like sandpaper.

“You…touched it?” she whispered in German.

Danny jerked awake, blinked, then smiled, the corners of his eyes creasing.

“Yeah,” he said. “Hab’s angefasst. And it didn’t burn me.”

She stared at him for half a second, then something broke loose in her chest. Quiet tears ran down her face, leaving clean tracks through the grime.

Nobody had touched that wound except her. Nobody had wanted to.

Three weeks later, she could sit up.

The aid station had moved twice since her surgery, following the line as Third Army rolled east, but the tent looked the same. The same cots, the same fatigue in the nurses’ eyes, the same background chorus of pain and bad jokes.

Danny was there again that morning, peeling back the dressing from her hip.

He whistled softly.

“Well,” he said, “would you look at that.”

The wound was no longer a horror. Pink, fragile new skin crept in from the edges. The deep red channel of the scar was still angry and knotted, but the black had gone. No more sour smell. No more fever.

Elsa watched him work, chewing her lip.

When he finished taping the fresh gauze down, she touched the scar very gently, fingertips hovering, then landing.

“It doesn’t burn anymore,” she said, halting English.

Danny smiled. “Good. That’s the point.”

She studied his face as he bent to toss the soiled dressings into a bucket. There was always something new to notice: the small scar by his jaw, the way his hands moved economically, never wasting motion.

“Du bist Jude,” she said suddenly. You’re Jewish.

He straightened, met her eyes, and nodded once.

“And you saved a German girl,” she said, the words half wonder, half shame.

Danny shrugged, a small, tired lift of the shoulders.

“I’m a medic,” he said. “Ich rette Menschen. I save people. That’s the job.”

“In Germany,” Elsa whispered, “they told us you would…do things. To us. To children.”

He held her gaze steadily.

“Some people do bad things,” he said. “Some do good. Today, I did good.”

He reached into his pocket and pulled out a small, cracked mirror from his kit.

“Hier. Look.”

She took it with trembling hands and angled it carefully, twisting just enough to see her lower back and hip. The scar slashed across her skin, long and jagged, an ugly railroad of twisted flesh.

Her stomach dropped. “Es ist hässlich. It is ugly.”

Danny shook his head.

“It’s proof you lived,” he said. “Survivor scar. You wear that proud.”

Over the next month, he was there every day.

When he wasn’t elbow-deep in someone else’s catastrophe, he was by her cot—changing dressings, bringing her extra rations he “found” in the American food line, smuggling in chocolate bars and swapped cigarettes.

He brought her American comic books one week, Superman in a translated edition some GI had picked up in Paris. He tried to explain the idea of a man in a cape flying around in his underwear saving people. She tried not to laugh and failed.

“This is your hero?” she asked in German, eyebrow raised. “He wears his underpants outside his clothes.”

“Don’t knock it till you try it,” Danny replied.

He taught her English phrases.

“Thank you.”

“It doesn’t hurt anymore.”

“That doctor is an idiot.”

She taught him Bavarian curses.

When she practiced the English swear words he snuck in—“damn,” then “hell,” then a few that made the nurse in the next cot gasp—he laughed so hard he had to sit down.

Sometimes at night, when the pain in her back flared red and hot and the tent walls pressed close, he would sit beside her and talk about Philadelphia. About snow that made the whole world quiet. About the way cheesesteaks tasted at two in the morning on a freezing corner. About his mother’s cooking and his father’s silence.

In return, she talked about Munich. Beer gardens in summer. The smell of pretzels and grilled sausages. The way the Glockenspiel figures spun in the Marienplatz when she was little and hadn’t learned yet that flags could poison everything.

One night, when the tent was lit only by a few dim lamps and the sounds outside had settled into the exhausted hum of a war that knew it was nearly over, she asked him softly:

“Why do you come…every day?”

Danny was quiet for a long time. The canvas walls shifted in the wind. Somewhere three tents down, someone coughed and swore.

“Because,” he said at last, choosing the words with care, “when I saw that wound, I knew somebody had decided you didn’t matter enough to save. I wasn’t going to be that somebody.”

Her eyes filled again, but this time the tears came with something else—anger, maybe, or a kind of rough, unfamiliar hope.

Three weeks later, the order came down. Prisoners were to be transferred to proper POW hospitals farther to the rear. Even the ones whose accents still made some of the staff bristle.

On the morning Elsa was due to go, an ambulance idled outside the tent. A nurse helped her into a clean dress someone had scrounged up. It hung loose on her frame, but it was cloth that didn’t reek of smoke or fear.

Danny came in holding a small cardboard box.

“For you,” he said.

Inside was a bar of chocolate, a small comb, and a tiny, folded American flag someone had drawn in colored pencil.

She smiled at the flag, then at him.

“Hab’ ich eine Bitte,” she said. I have one request.

She held out her hand.

“Your dog tags. Just for a moment.”

He hesitated, then slipped the chain over his head and placed the tags in her palm. They were warm from his skin. She pressed them to her lips, eyes closed, then handed them back.

“Du hast das Feuer für mich berührt,” she said. “You touched the fire for me. I will never forget.”

He watched as they helped her out to the ambulance, cane in one hand, grip tight on the rail. She turned once and raised a hand in an awkward little wave. Then the doors closed and the vehicle pulled away, wheels throwing up muddy water.

He never saw her again.

Three weeks after the surgery, the war rolled on. The tent moved again. New casualties arrived. The old ones were discharged or buried. Danny kept working, hands steady, eyes older than his years.

April turned into May. Germany surrendered.

He went home to Philadelphia eventually, finished school on the GI Bill, lived a life.

And every year on 17 April, without fail, a postcard arrived from Germany.

Different towns. Different pictures. Always anonymous. Always the same careful English in a woman’s hand:

It doesn’t burn anymore.

Thank you for touching it.

He never answered. There was no return address.

He’d take the card, read the words once, twice, then tuck it into a shoebox where the others lived. Sometimes, on quiet winter nights, he’d open the box, flip through the stack, and remember a dirty tent near the Rhine, a girl who thought her wound was poison, and the way it felt to put his hands into that ruin and refuse to pull them back.

Decades later, in 1995, a groundskeeper at a cemetery near Stuttgart watched an old woman visit an American grave just after dawn.

She walked slowly, leaning on a cane. In one hand, she carried a small cloth bundle.

She laid the bundle on the stone and unfolded it carefully.

Inside was a sky-blue dress, fragile with age, and beneath it, sealed in glass, a single stained scrap of gray wool—the remnant of a Luftwaffe helper’s uniform.

She spread the blue dress like a blanket over the grave and rested the glass-shrouded scrap on top.

“Du hast es einmal berührt, um mir morgen zu geben,” she whispered. You touched it once to give me tomorrow. “I wore the new one for fifty years. Today I bring them both back. So you know I never forgot.”

She knelt, kissed the cold stone, stood with difficulty, and raised one trembling hand in an American-style salute before she walked away.

All that summer, visitors noticed the faded blue cloth on the grave, never quite washed out by rain or sun. In the years after, on every April 17th, they found a fresh blue ribbon tied around the headstone and a single red rose laid at its base.

No one ever saw who left them.

The staff just knew that once a year, an old woman with a limp would come and sit on a nearby bench, watching in silence, her hand resting unconsciously on a scar hidden beneath her clothes.

Because some wounds aren’t just torn flesh. They’re the exact moment someone decided you still mattered.

And some scars don’t just mark survival.

They remember the hands that touched the fire and didn’t let go.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.