“I Can’t Close My Legs” — The Exam Room at Camp Swift

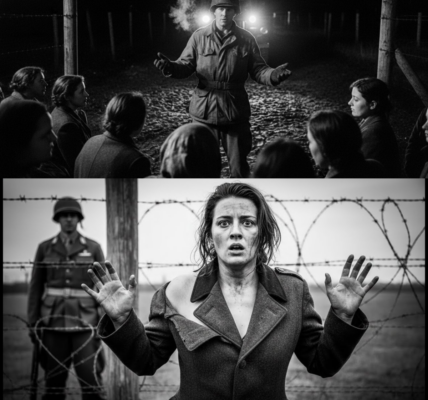

July 1945, Camp Swift, Texas.

The war in Europe had been over for weeks, but the heat in Texas didn’t care about surrender documents or victory parades. It sat on the buildings like a weight. It pooled in corners and clung to skin, turning every movement into effort. Inside the Army exam room, the air was hot and unmoving, a stale mixture of disinfectant, dust, and old canvas. A tired ceiling fan clicked above a worn table, pushing warm air in slow circles that didn’t cool anything—only reminded you that time was passing.

Captain David Morrison, forty-two, stood beside the exam table and rolled his shoulders to loosen the stiffness from a day of back-to-back examinations. He had been a doctor in Philadelphia before the Army took him and the war taught him new definitions of injury. He had treated men torn by shrapnel in North Africa. He had watched malaria hollow out bodies in Italy. He had seen lungs drown in infection and stomachs starved by bad rations. He believed he knew what war did to flesh.

He was wrong—at least about the limits of it.

The door opened with a soft metal squeak.

A young woman appeared in the doorway. She didn’t step in immediately. She gripped the door frame like it was a crutch, her fingers white with effort, as if the room itself might knock her down. She wore a faded German uniform that hung on her like an oversized coat. Her hair was pulled back, but the style couldn’t hide how thin her face was. Her eyes looked too large, as if her skull had become a little too big for the rest of her.

Lieutenant Sarah Chun from the Women’s Army Corps stood at her side, one hand hovering near the woman’s elbow—not quite holding her, but ready, the way you stand beside someone who might collapse if you stop paying attention for even a second.

“This way,” Chun said gently, guiding her toward the examination table about twelve feet away.

It should have been easy. Twelve feet. A handful of steps. A distance so small it was almost insulting to measure.

But the young woman moved like she was crossing a battlefield.

Her name, according to the paperwork, was Keith Schmidt—twenty-four years old. She looked younger and older at the same time: younger in the soft shape of her features, older in the way her body seemed to negotiate with gravity. Morrison watched her begin. One step, and her legs shook so hard her knees visibly trembled. A second step, and her hand shot out to the wall. She leaned into it, breathing hard, as if she had climbed a hill instead of crossing two feet of linoleum.

It took her nearly a full minute to reach the table.

Morrison felt something tighten in his chest—not fear, exactly, but a kind of stunned alarm, the sensation you get when you realize you’ve been assuming the wrong danger.

Through an interpreter, Morrison said, “Please walk to the table.”

Keith had already done it, but he heard himself say it anyway because his mind still expected her to be able to do what twenty-four-year-olds do.

She looked up once, briefly—just long enough for him to see the strain in her eyes—and then looked down again as if eye contact would cost energy she couldn’t afford.

When she reached the table, she didn’t sit immediately. She stood there, swaying faintly.

Morrison began with the basics. The nurse called out numbers while she wrote them down in careful, practiced handwriting.

“Height: five foot six.”

“Weight: eighty-seven pounds.”

Eighty-seven.

For a moment, Morrison’s mind refused to accept it. He had to replay it internally like a misheard radio transmission. Five foot six and eighty-seven pounds. A healthy woman that height might weigh one hundred thirty, one hundred forty. He did the math instinctively. His training was automatic. Body mass index around fourteen. Normal would be near twenty, twenty-one.

This wasn’t “thin.”

This was danger.

Her blood pressure was low. Her pulse was fast but weak, a rapid little flutter under his fingers. Her temperature was slightly raised—not a fever that screamed infection, but enough to suggest her body was under constant stress.

Up close, the hollowness of her cheeks was startling. Skin drawn tight over bone. Lips dry. Her eyes—huge, unblinking—held a kind of wary resignation that Morrison had seen in soldiers who had been in foxholes too long.

“I need to examine your legs and feet,” he said. “Please remove your shoes and socks.”

Keith stared down at her boots as if the request were unfamiliar, as if “remove” were a complicated operation. Her fingers trembled when she bent to untie the laces. The leather was cracked, rubbed shiny at the heels, the kind of shine that came from endless marching rather than polish. The room was quiet except for the clicking fan and the slow scrape of lace against eyelet.

Then she spoke, not through the interpreter this time, but in halting English—as if the sentence mattered so much she wanted to force it out in the language of the people who might save her.

“I… I can’t close my legs,” she whispered.

Morrison blinked. He thought he had misheard.

Keith swallowed and tried again, her voice barely louder than the fan. “I can’t close my legs. They shake.”

Her hand lifted, touching the sides of her knees. “It hurts here.”

Morrison’s first assumption—like almost every American doctor in an Army camp—was that he was about to see a wound. A hidden injury. A fracture. Maybe some trauma she couldn’t name. Maybe something that happened during capture, something she was afraid to describe.

“Take off the boots,” he said, keeping his voice calm.

Keith pulled off the first boot.

The smell hit the room immediately—old sweat, damp cloth, and something sharper beneath it, sour and unmistakable: the smell of wounds that had been trapped too long in fabric and leather.

Lieutenant Chun stiffened. The nurse made a small involuntary sound and caught herself.

Keith peeled away the thick sock.

Morrison looked down, and for a moment he lost his calm.

Her calves were no more than sticks wrapped in skin. There was almost no muscle. The shin bone and ankle bone pushed forward like the edges of tools under thin cloth. Her skin looked pale and stretched, almost translucent, blue veins webbing across the top of her foot.

But the worst part wasn’t the thinness.

It was the sores.

Around her ankles and along the sides of her feet were open ulcers—round, angry patches of raw flesh. Some had yellow edges that suggested infection. Some were red and wet as if the skin had been rubbed away only yesterday. In places, the boot had rubbed straight through skin until the wound looked perilously close to bone.

Keith pulled off the second boot. The second sock.

More sores. More rawness. More evidence that her body had been moving long after it should have stopped.

Morrison’s eyes lifted to her knees, then to her hips. He understood why she couldn’t close her legs. It wasn’t a mysterious injury. It wasn’t a bullet wound. It was something slower and, in some ways, more horrifying.

It was starvation.

Not the kind of hunger Americans imagined when they skipped lunch. Not the brief scarcity you endured and shrugged off. This was months of the body consuming itself. Months of muscle dismantled piece by piece, leaving bones and skin and a failing engine struggling to move.

And the strangest part—because starvation never arrives alone—was swelling.

Her ankles were puffy with fluid, edema sitting above the sores, even though the rest of her was emaciated. Thin legs ending in swollen joints. The contrast made Morrison’s stomach turn. It was a classic sign of the body failing: protein depleted, blood chemistry collapsing, fluids shifting where they didn’t belong. The system trying to hold on to water and salt because it couldn’t hold on to anything else.

Morrison wrote later, in words that were clinical only because medicine demanded a kind of distance:

“Lower limbs show extreme muscle wasting. Multiple pressure ulcers on feet and ankles, some infected. Edema present at ankles despite overall emaciation.”

He had seen hunger before.

He had never seen it cut this deep into a young woman’s body.

“How long have you had trouble walking?” he asked.

The interpreter translated.

Keith’s answer came soft, almost ashamed, as if she had failed some test of strength.

“Since January,” she said, then corrected herself. “Maybe February. The rations became small… then very small… then almost nothing.”

She swallowed, and Morrison saw her throat move sharply beneath skin that seemed too tight.

“My legs,” she added, as if she were explaining a betrayal. “They stopped listening to me.”

Morrison stared at her feet and realized something that felt like a cruel paradox. Outside the camp, American fields were full. Soldiers ate three meals a day. In this room, in one of the richest food nations on Earth, an enemy prisoner stood at the edge of death from hunger.

This wasn’t propaganda.

It was bone and sores and trembling legs.

Morrison finished the exam in a kind of controlled silence. His face stayed neutral because doctors learn early that a patient reads your expression like a verdict. But inside, his thoughts were racing.

If Keith looked like this, then others might too.

And if others looked like this, then Camp Swift wasn’t just holding prisoners.

It was receiving medical emergencies.

That night, after the day’s examinations ended, Morrison sat at a desk under a dim lamp and wrote a report more detailed than any he had filed in months. He listed every number carefully:

Height: 5’6”. Weight: 87 pounds. Estimated BMI: ~14. Severe underweight. Marked muscle loss. Multiple infected pressure sores. Signs consistent with prolonged malnutrition.

At the end, he wrote the line that would change everything:

Recommend full examination of all female prisoners in this transport. Suspect prolonged severe malnutrition may be common.

The next morning, he placed the report in the hands of Major Thomas Henderson, the camp’s chief medical officer.

Henderson read it slowly. His jaw tightened. He looked up and said, “This is worse than we expected.”

“We knew Germany was short of food,” Morrison replied. “But this isn’t just short. This is collapse.”

Henderson tapped the paper with his finger. “Examine the rest,” he said. “All of them. Document everything. We need facts.”

And for the next three days, the exam room became a quiet machine for discovering how war kills long after the shooting stops.

One by one, women from Keith’s transport entered. The air stayed the same: disinfectant, warm dust, old wool. Morrison and Lieutenant Chun moved through the same steps each time—height, weight, blood pressure, pulse, skin, gums, then legs and feet. And the numbers piled up like grim arithmetic.

Many were not as bad as Keith.

But too many were bad enough.

Thin faces. Loose uniforms. Weak grips. Trembling steps. Bleeding gums. Brittle nails. Swollen ankles above wasted calves. Wounds where boots had rubbed through skin because there was no padding left, no muscle to protect bone.

And the stories—whispered through interpreters, sometimes in broken English—matched each other.

Rations cut again and again. First sugar, then meat, then bread. Promises on paper that meant nothing when trains didn’t arrive. Bombed rail lines, burned warehouses, cold winters, endless walking.

Keith’s body wasn’t an exception.

It was a pattern.

When Morrison finished examining the group, he assembled a second report: tables of heights and weights, summaries of symptoms, a conclusion that was impossible to ignore.

These prisoners were not simply “underweight.”

A significant number were in life-threatening malnutrition.

Henderson called a meeting of the medical staff. The room was crowded—doctors, nurses, corpsmen. Windows were open, letting in warm Texas air and the distant sound of trucks. Henderson held up the report.

“This is not isolated,” he said. “If we process these prisoners with routine intake, some will die in our custody from starvation that began months before they ever reached Texas.”

A doctor asked, uncomfortable, “Are we equipped for this level of care for enemy prisoners?”

Henderson’s answer was simple. “We will have to be.”

The Geneva Convention demanded adequate treatment. But Henderson didn’t even lead with that. He led with something older than law: a physician’s obligation to a body in front of them.

New rules were written.

Every incoming POW transport would receive a full medical exam with special attention to nutritional status. Anyone dangerously underweight would be flagged and monitored. Anyone with signs of vitamin deficiency would receive supplements. Anyone with infected wounds would be treated before being assigned to regular barracks duties.

A barracks was converted into a special ward for nutritional recovery.

And Keith Schmidt—who had entered the exam room whispering, “I can’t close my legs”—was moved into it with the worst cases.

The ward smelled like soap, boiled linens, weak broth, and disinfectant. The beds were plain. The sheets thin. But to bodies that had known only cold floors and endless marching, it was a kind of miracle.

Feeding them, Morrison knew, was not as simple as putting a full plate in front of them. A starving body can be fragile in strange ways. Too much too fast could shock the system. The heart, already strained, might fail. Electrolytes could swing dangerously. So the plan was careful and strict: small meals, gradually increasing calories, constant monitoring—pulse, temperature, blood pressure, daily weights.

For the first days, the food looked almost insulting: thin oatmeal, broth, soft bread, weak tea. But to the women, it was more than food. It was proof that the world still contained abundance.

Keith ate slowly. Not because she was savoring it, but because her stomach cramped, as if it didn’t remember how to work. After a few bites she looked at her bowl, eyes wide, and whispered to the nurse, “There is so much.”

Chun crouched beside her. “Small bites,” she said gently. “You’ll get there.”

The first week, weights barely moved. Some women gained a pound, some none. The swelling in ankles sometimes eased before true weight returned, confusing to anyone who expected recovery to be linear.

Morrison told them, again and again, “This takes time. Your body is learning again.”

Gradually, the meals grew richer. More potatoes. More protein. Supplements added—vitamins that tasted chalky but carried life back into gums and nerves and blood.

Wounds were cleaned and dressed daily. The sores that had looked like evidence of irreversible decay began to close at the edges. Redness softened. Infection retreated. Pain lessened enough for the women to stand without biting their lips until they bled.

Then came movement—careful, humiliating at first.

Standing beside the bed.

A few steps in the ward.

Holding a nurse’s elbow like a child learning to walk.

Keith’s legs still shook. She still couldn’t close them fully without pain at first because weakness made control impossible. But she began to feel something she hadn’t felt in months: responsiveness. A faint return of strength like a signal flickering back into a dead radio.

One day during a check, she told Morrison, “There is less fog in my head.”

Morrison nodded, writing it down. In medicine, tiny changes are sometimes the most meaningful.

As strength returned, the women began to speak more. Not just about symptoms, but about the road that brought them here. And the story, as Keith had hinted, did not start in Texas. It began months earlier, in a Germany running out of everything.

Keith had not been a frontline soldier. She had been an office clerk near Hamburg, surrounded by forms and schedules and the comforting illusion of order. Even late in the war, Germany clung to paperwork like a lifeline. Forms were stamped. Lists were typed. Rations were counted.

At first, the war brushed her life like distant thunder. Then the bombs came more often. Hamburg burned again and again. Sirens screamed. Warehouses went up in flames. Rail lines twisted. Entire districts became black ruins.

And then, quietly, the numbers on her forms began to change.

Trains that were supposed to arrive did not. Supplies that were supposed to be delivered never came. Food promised on paper vanished into smoke and distance. The ration cards still existed, but the meaning of a card collapses when there is nothing behind it.

Rations became smaller, then very small. First sugar, then meat, then bread. By late 1944, Keith said, civilians in many cities lived on around 1,200 calories a day—sometimes less. Office workers were low priority. Soldiers at the front came first. Factory workers next. People like Keith were near the bottom.

The irony, she would later say, was sharp enough to cut: she worked in supply and became one of the last to receive supplies.

By January 1945, her meal was thin soup and a crust of bread. Some days only soup—warm water with turnip or potato skins. The winter cold cut through walls and coats. Standing at her desk made her lightheaded. Climbing stairs stole her breath. Her skirt hung loose, belt punched with extra holes.

By March, many ate one “real” meal a day—if it could be called real. They ate anything: dandelions, nettles, beet tops. Biscuits bulked with sawdust. Not because they believed it was food, but because the body’s panic does not care about dignity.

Then, as supply lines broke completely, came movement—retreat, marching, relocation from one makeshift post to another. Always walking, always hungry. Boots that once fit began to slip because flesh had disappeared. Leather rubbed raw paths into skin. Each day of marching opened sores deeper.

Keith remembered days with no food at all. Walking anyway because stopping meant being left behind.

“Some people sat down,” she said quietly, “and did not get up again.”

When British forces captured her group in May 1945, she weighed around ninety pounds. She was given basic rations—enough to slow the freefall, but not enough to rebuild. Then she moved through temporary camps and was handed to American control.

The Atlantic crossing took about two weeks. The ship smelled of fuel, metal, and crowded bodies. Sea sickness took what little she could eat. By the time she reached New York processing, she could barely stand. The train ride to Texas blurred into rattling wheels and careful steps to a latrine, always holding someone’s arm.

So when she entered the Camp Swift exam room in July 1945 and whispered, “I can’t close my legs,” it wasn’t a sudden injury.

It was the final expression of months of collapse.

Back in the ward, Keith gained weight slowly. Not dramatic, not cinematic—just small, stubborn increments. A pound. Another. The swelling eased. The wounds tightened and closed. The constant chill inside her bones faded. Her eyes looked less like they were floating in her skull and more like they belonged to her face.

She began walking farther. First the length of the ward, then outside, then across parts of the compound. She still moved carefully because her feet carried scars, but she moved under her own control, no longer negotiating with gravity one trembling step at a time.

And the most important thing for Morrison—the thing that would outlive the paperwork—was that Keith was not the only one helped by what happened in that exam room.

Because Henderson’s new policies spread through the camp system. Transports arriving later were examined differently. Underweight prisoners were flagged earlier. Wounds were treated before infection could deepen. Supplements were administered before gums bled and teeth loosened. The system changed, not because someone in a distant office ordered it, but because one doctor saw the truth in front of him and refused to treat it like a minor detail.

This, Morrison understood, was one of war’s strangest legacies: a conflict that stripped humanity from so many places could, in one small room, force it back into focus.

Keith had come into the exam room as an “enemy prisoner,” a category stamped onto paper.

But when Morrison looked down and saw bones and sores and starvation, the category lost meaning.

He saw a patient.

And that decision—quiet, almost mundane compared to battles and headlines—shifted something real.

In the richest food nation on Earth, an enemy prisoner had arrived at the edge of death from hunger.

And in a hot, still exam room under a clicking fan, an American doctor chose to treat the truth of that hunger as urgently as any shrapnel wound.

Not because he was trying to rewrite history.

But because medicine, at its core, is not allegiance.

It is response.

And sometimes the most powerful response begins with a whisper:

“I can’t close my legs.”

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.