How One Plumber’s ‘RIDICULOUS’ Pipe Idea Saved 5,000 Bomber Engines

March 15th, 1944. Pratt Army Airfield, Kansas. Captain Robert Morgan watches flames erupt from the number three engine of his B29 Superfortress. The right R3350 engine, 220 horsepower of American engineering is cooking itself alive at 600° F. Black smoke pours from the cowling as ground crews sprint toward the aircraft with fire extinguishers. It’s the fourth engine fire this week. on this airfield alone. Morgan kills the fuel mixture and hits the fire suppression system. Nothing happens. The extinguisher bottles designed to flood the engine compartment with carbon dioxide can’t reach the source of the blaze.

The fire is burning in the rear cylinders, trapped behind baffles and cooling fins where the extinguishing agent can’t penetrate. Everybody out,” Morgan screams. His crew evacuates in 45 seconds flat. They’ve practiced this drill so many times, it’s become muscle memory. By the time the fire trucks arrive, the $600,000 bomber is a total loss. The fire has melted through the main wing spar. The entire aircraft will be scrapped for parts. But here’s what makes this moment absolutely terrifying.

This is not a combat loss. This is Kansas. This is a training flight. The B29 never even left American airspace and it’s happening everywhere. At Smoky Hill Army Airfield, another B29 burns on the runway. At Walker Field in Kansas, two more catch fire during engine run-ups. At Great Bend, a Superfortress explodes during takeoff, killing all 11 crew members before the aircraft even becomes airborne. The statistics are catastrophic. Of the first 175 B29s delivered to the Army Air Forces, 16 have burned completely.

Another 47 have suffered major engine fires. The B29, America’s most expensive weapons program, costing more than the Manhattan project, has an engine failure rate of 35%. 35%. General Henry Hap Arnold, commanding general of the Army Air Forces, faces a nightmare. He’s promised President Roosevelt that B29s will be bombing Japan by June 1944. But at the current rate, the program will kill more American air crews in training accidents than the Japanese will shoot down in combat. What nobody knows, what nobody can possibly predict as Morgan watches his bomber burn is that the solution to this crisis won’t come from Wright Aeronautical Corporation’s team of elite engineers.

It won’t come from Boeing’s design department. It won’t even come from the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, where the nation’s top aeronautical experts are desperately trying to solve the problem. The solution will come from a 38-year-old aircraft mechanic with a seventh grade education who spent 15 years before the war installing residential plumbing in Cleveland, Ohio. His name is Tony Validor and his ridiculous idea about pipes is about to save the entire B29 program. The clock is ticking.

Japan is building defenses. American bombers are burning on American runways and Tony Validor is about to suggest something so simple, so obvious that the engineers will laugh him out of the room. The right R3350 duplex cyclone is supposed to be the most powerful radial engine ever built. 18 cylinders arranged in two rows, 2200 horsepower, capable of pushing the B29 to 350 mph at 30,000 ft. On paper, it’s magnificent. In reality, it’s a death trap. The problem is heat, specifically rear cylinder heat.

Each R3350 engine has nine cylinders in the front row and nine in the rear. The front cylinders get plenty of cooling air. Ram air rushing through the engine cowling at 200 mph. But the rear cylinders sit in the shadow of the front row, starved for air flow. Temperatures in the rear cylinders climb to 550° F during normal operation. During high power climbs, like takeoff, temperatures spike to 650°. The aluminum cylinder heads begin to warp at 500°. Exhaust valves fail at 575° and at 600°, the entire cylinder can seize, causing the piston to stop moving while the crankshaft continues rotating at 2,800 RPM.

When that happens, connecting rods snap. Pistons punch through cylinder walls. Hot oil sprays across superheated metal. The magnesium alloy engine cases ignite, burning at 5,600 degrees Fahrenheit, hot enough to melt through the aluminum wing spar in 90 seconds. The B29’s onboard fire suppression system is useless because the fire is burning inside the engine where the extinguishing agent can’t reach it. Boeing’s engineers try everything. They increase the size of the cooling air intake. Doesn’t work. Rear cylinders still overheat.

They install larger oil coolers. Marginal improvement, but not enough. They redesign the cowl flaps. The adjustable panels at the rear of the engine cowling that control cooling air flow. The new design creates so much aerodynamic drag that pilots can’t fully open the flaps during takeoff without losing critical air speed. Write Aeronautical sends a team of their best engineers to investigate. They discover that the cylinder baffles, thin aluminum sheets designed to direct cooling air over the cylinder heads, have insufficient clearance.

There’s barely half an inch of space between the baffles and the cylinder cooling fins. Air can’t flow efficiently through such a narrow gap. The solution seems obvious. Increase the clearance. Redesign the baffles. Give the air more room to flow. But there’s a problem. The entire engine cowling is already designed around the existing baffle configuration. Changing the baffles means changing the cowling. Changing the cowling means changing the wing structure. Changing the wing structure means redesigning the entire aircraft.

Boeing estimates it would take 18 months and cost $50 million to implement such changes across the production line. General Arnold doesn’t have 18 months. He doesn’t have 18 weeks. The first B29 combat missions are scheduled for June 5th, 1944, less than 12 weeks away. The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, NACA, the predecessor to NASA, gets involved. In June 1944, they bring a B29 to their aircraft engine research laboratory in Cleveland, Ohio. Teams of engineers run the engines in their massive altitude wind tunnel, simulating flight conditions at 30,000 ft.

The engineers confirm what everyone already knows. inadequate air flow to the rear cylinders. But here’s the expert consensus. The problem is fundamentally unsolvable without a complete engine redesign. The R3350 is simply too powerful, generating too much heat in too small a package. The laws of thermodynamics are against us. By September 1944, the situation is desperate. 414 B29s will be lost during World War II. Only 147 will be shot down by enemy action. The other 267, nearly 2/3, will be lost to engine fires and mechanical failures.

2/3 lost to their own engines. The 20th Air Force is losing bombers faster than Boeing can build them. Crews are terrified. Pilots call the B29 the flying funeral p. Some air crew request transfers to B17s and B-24s, older, slower, less capable aircraft because at least those planes don’t randomly catch fire over friendly territory. At Wrightfield in Dayton, Ohio, at the NACA laboratory in Cleveland, at Boeing’s plant in Witchah, everywhere the best aviation mines in America are working on this problem, the answer is the same.

There is no solution. Not without starting over. What they don’t know is that in a maintenance hanger at Pratt Army Airfield, a mechanic who used to install copper pipes in Cleveland basement is staring at an R3350 engine and thinking about water pressure. Antonio Tony Validor is nobody’s idea of an aircraft engineer. Born in 1906 in Cleveland’s Little Italy neighborhood, Tony drops out of school at age 14 to help support his family. His father runs a small plumbing business, residential work, mostly, installing sinks, fixing toilets, running water lines through old houses where the pipes don’t want to cooperate with the walls.

Tony learns the trade the hard way. frozen knuckles, crawling through basement, figuring out how to root pipes through impossible spaces. By age 20, he’s one of the best troubleshooters in Cleveland. When water won’t flow, when pressure drops mysteriously between floors, when a heating system develops cold spots, Tony is the guy who figures out why. The secret, Tony learns, is understanding flow. Water doesn’t care about blueprints. It takes the path of least resistance. If you want water to go somewhere, you don’t force it.

You guide it. You create a path where flowing is easier than not flowing. When the war starts in 1941, Tony is 35 years old, too old for combat, but young enough for war work. He applies to Curtis Wright, thinking his experience with pipes and fluid flow might translate to aircraft manufacturing. They assign him to engine maintenance at Pratt Army Airfield. Tony has never worked on aircraft before. Everything he knows about engines comes from a 3-week training course, but he knows pipes.

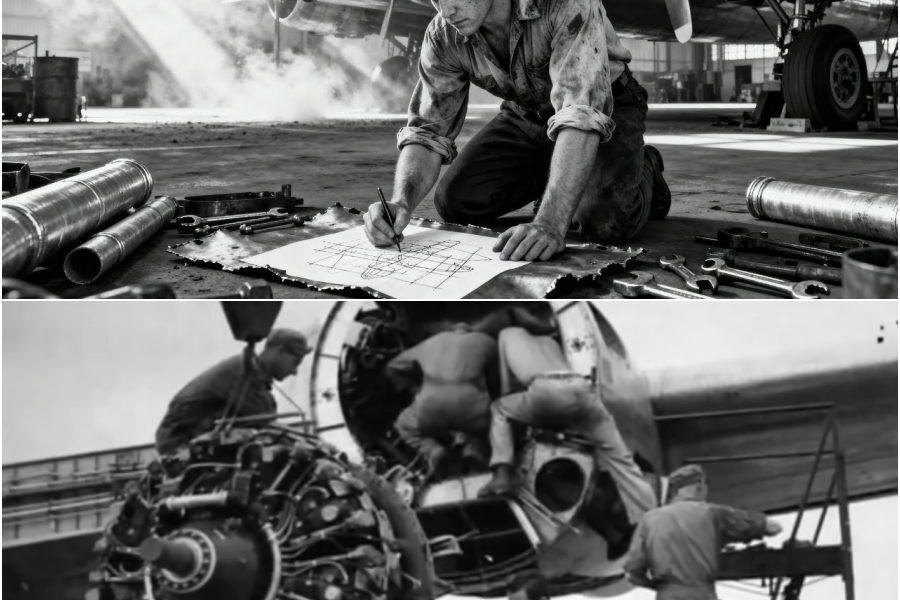

He knows flow. And when he looks at the R3350 engine, really looks at it the way a plumber looks at a problem water system, he sees something the engineers don’t. It’s September 1944. Tony is working the night shift, performing routine maintenance on engine number three of a B29 that suffered an overheat warning during a training flight. The pilot shut down the engine before it caught fire, so Tony’s job is to inspect for damage. He removes the cowling panels and stares at the rear cylinders, blackened, heat stressed.

The cooling fins are discolored, a telltale sign of sustained high temperatures. Tony traces the path cooling air is supposed to take. It enters through the intake at the front of the cowling, flows over the front cylinders, then in theory flows between the cylinder rows to cool the rear cylinders. But looking at the actual geometry, Tony realizes something. The air isn’t flowing. It’s stagnating. The front cylinders heat the incoming air to 300°. That hot air tries to flow rearward, but there’s no exit path.

The air gets trapped between the cylinder rows, growing hotter and hotter until it’s actually heating the rear cylinders instead of cooling them. It’s exactly like the time Tony had to fix the third floor radiators in that apartment building on Uklid Avenue. The hot water was taking the easy path straight to the second floor and never reaching the third floor because there was no pressure differential forcing it upward. The solution then was simple. Tony installed a small bypass pipe that redirected some of the flow.

Standing in the maintenance hanger, staring at a4 million dollar aircraft engine, Tony thinks, “What if I do the same thing here? What if instead of trying to force cooling air through the engine, I route it around?” He sketches it out on the back of a maintenance log. small pipes, ducting, a bypass system that redirects cooling air directly to the rear cylinders, creating a dedicated cooling path that doesn’t depend on airflow between the cylinder rows. It’s simple, almost stupidly simple, which is exactly why Tony knows the engineers will hate it.

Tony spends the next three nights building his prototype. He can’t use official channels, requisitioning parts, getting engineering approval because he knows what will happen. The engineers will look at his seventh grade education and his plumber’s background and laugh him out of the office. So Tony improvises. He scavenges aluminum tubing from a damaged B29 awaiting salvage. He borrows a cutting torch from the welding shop. He uses tin snips to modify the cylinder baffles, creating new openings. He fabricates small aluminum duct, essentially pipes that root cooling air around the front cylinders directly to the rear.

The duct are crude, handformed, held together with sheet metal screws and high temperature sealant. They look like something a plumber cobbled together in a basement because that’s exactly what they are. But the principle is sound. Instead of hoping air will naturally flow rearward through a complex maze of obstructions, Tony’s ducks force the air along a dedicated path. It’s the same principle as a water bypass line. Create a lowresistance path directly to where the flow is needed. On the night of October 3rd, 1944, Tony finishes installation.

He’s modified the right inboard engine of B29 serial number 42244605, a training aircraft that’s already scheduled for an engine test run the next morning. He doesn’t tell anyone. He just signs off on the maintenance report. Cooling system inspection complete. Engine cleared for test. The next morning, Captain James Wheeler is assigned to perform the engine runup. Standard procedure. Run the engine through power settings. Monitor temperatures. Check for anomalies. Wheeler advances the throttle. The R3350 spools up to full power.

2800 RPM, 2200 horsepower. The noise is deafening. The airframe shakes, but the rear cylinder temperature gauge, which normally climbs to 550° within 90 seconds, holds at 425°. Wheeler thinks the gauge is broken. He continues the test for 5 minutes at full power. Longer than normal, longer than safe if something’s actually wrong. Rear cylinder temperature 430°. Front cylinders 410°. The rear cylinders are actually cooler than the fronts. Wheeler shuts down the engine and immediately reports to the engineering officer.

Something’s wrong with number three. Temperature readings are impossible. Gauge must be faulty. They send a maintenance crew to investigate. That’s when they discover Tony’s modification. When the engineering officer sees the hand fabricated aluminum ducks, he goes ballistic. Who authorized this? Who performed an unauthorized modification to a combat aircraft engine? This is a court marshal offense. Tony is pulled from the flight line, brought before Major Donald Peterson, chief of aircraft maintenance. Did you modify that engine without authorization?

Yes, sir. Do you understand you could face criminal charges? Unauthorized modifications to military aircraft. Sir, the rear cylinders ran 60° cooler. I have a solution to the overheating problem. Peterson stares at him. You have a solution, son. NACA has 50 engineers working on this problem. Wright Aeronautical has their entire design team working on it. Boeing has with respect, sir, they’re all overthinking it. It’s a plumbing problem. The air needs a dedicated flow path. I gave it one.

You’re a mechanic. You don’t have the qualifications to I’m a plumber, sir. And in plumbing, when fluid won’t flow where you need it, you add a bypass. That’s all I did. Major Peterson looks at the temperature logs from the test run. 60° cooler. Sustained full power operation with no temperature rise. That’s impossible, Peterson says. Permission to run another test, sir. Let me prove it’s not. October 5th, 1944, right field, Dayton, Ohio. Major Peterson doesn’t trust Tony’s modification, but he can’t ignore the temperature data.

He forwards the test results to right field with a simple note. Mechanic modified R3350 cooling system. Achieved 60° temperature reduction. Recommend immediate evaluation. Two days later, Tony finds himself on a C-47 transport to Dayton, carrying his handbuilt aluminum ducks in a canvas bag like a plumber bringing his tools to a job site. At right field, he’s escorted to a conference room where 12 engineers from Wright Aeronautical, Boeing, NACA, and the Army Air Forces are waiting. They’ve heard about the plumbers’s modification.

They’re not impressed. Colonel Curtis E. Lame, commander of the B29 program in the Pacific theater, is visiting right field and decides to sit in on the meeting. Lame is legendary for his intolerance of bureaucratic nonsense. He needs B29s that don’t catch fire. He doesn’t care who solves the problem. Dr. Harrison Evans, chief aeronautical engineer from Wright Aeronautical, opens the meeting. Sergeant Validor, we’ve reviewed your temperature data. While the results are interesting, we have significant concerns about your approach.

What concerns, sir? For starters, you’ve created turbulent flow paths that violate fundamental principles of aerodynamic cooling design. The ducts you’ve installed actually reduce total cooling air flow by approximately 8% according to our calculations. But the rear cylinders run cooler. That’s well, it’s probably a measurement error. The thermouples may have been improperly positioned after your modification. Tony pulls out a second set of temperature logs. I ran three more tests, sir. Different thermouples. Same results. Rear cylinders consistently 50 to 65° cooler than baseline.

A Boeing engineer speaks up. Even if your data is accurate, your modification is completely impractical for production. Those handfabricated ducks would require custom manufacturing. We can’t tool up for something like this across the entire fleet. Why not? They’re just aluminum tubes. Any sheet metal shop can make them? Because they’re not engineered. There’s no stress analysis, no vibration testing, no long-term durability assessment. They’re cooling ducks, not loadbearing structures. The room erupts. You don’t understand the complexity. These engines cost $35,000 each.

We can’t just let mechanics start modifying engines based on hunches. This is exactly the kind of cowboy engineering that gets people killed. Colonel Lame stands up. The room goes silent. Gentlemen, shut up. Lame looks at Tony. Sergeant, I have B29s burning up on Saipan. I have crews refusing to fly because they’re more afraid of their own engines than they are of Japanese fighters. Now you’re telling me you can fix this problem with some aluminum tubes? Yes, sir.

And these experts are telling me it can’t work because it’s not properly engineered. Is that about right? Yes, sir. Lame turns to Dr. Evans. How long has Right Aeronautical been working on this cooling problem? Since early 1943, Colonel. Approximately 20 months. 20 months. And what solutions have you implemented? We’ve we’ve made incremental improvements to cylinder head design, modified the baffle clearances within existing constraints, optimized the cowl flap actuator schedule. Has any of it worked? Silence. I asked you a question, doctor.

Has any of it worked? Not not to the degree we’d hoped. Lame looks at the temperature logs. Sergeant Validor achieved a 60° temperature reduction with aluminum tubes he made in a maintenance hanger in one night using scrap parts. He drops the logs on the conference table. Here’s what’s going to happen. You’re going to take Sergeant Validor’s modification. You’re going to engineer it properly. Stress analysis, vibration testing, whatever you need to do, and you’re going to get it into production.

Not in 20 months, not in 20 weeks, in 20 days. Colonel, that’s impossible. Then you’d better work fast because in 30 days, I’m bombing Japan with 500 B29s, and I need engines that don’t burn up over the Pacific. Sergeant Validor has shown you how to fix it. Now do your job and implement it. The room is silent. Lame turns to Tony. Sergeant, you’ll remain at right field as a technical consultant. These gentlemen are going to have questions about your modification.

You’ll answer them. Yes, sir. Lame heads for the door, then stops. And sergeant, don’t let these engineers over complicate this. Sometimes the best solution is the simple one. CTA number one, 12minute mark. This is the moment when everything changed. But the real challenge was just beginning. Before we see how Tony’s simple idea transformed the entire B29 fleet, take 10 seconds to subscribe if you’re learning something incredible today. We bring you untold stories that changed history. Stories most people have never heard.

Hit that subscribe button and let’s continue this remarkable journey. October 15th, 1944, right field testing facility. Tony’s modification undergo the most intensive testing in aviation history. Wright Aeronauticals engineers take his crude hand fabricated ducks and reverse engineer them. They create proper technical drawings. They run computational fluid dynamics analyses primitive by modern standards but state-of-the-art for 1944. They install calibrated thermouples at 36 measurement points throughout the engine. The testing protocol is brutal. Run the engine at full power for 2 hours straight.

Twice as long as any B29 would ever maintain maximum power in actual operations. Monitor every temperature, every pressure, every vibration frequency. The results shock everyone. Baseline R3350 without modification. Front cylinder temperature 410° average. Rear cylinder temperature 565° average. Peak rear cylinder temperature 627°. Time to exhaust valve failure at full power 73 minutes. Modified R3350 with validor ducks. Front cylinder temperature 415° average. Rear cylinder temperature 445° average. Peak rear cylinder temperature 478°. Time to exhaust valve failure at full power.

No failures observed after 180 minutes. The rear cylinders are running 120 degrees cooler. The temperature differential between front and rear cylinders, which was 155°, is now just 30°. Dr. Evans from Wright Aeronautical runs the numbers three times, convinced there must be an error. There isn’t. How is this possible? He asked Tony. The ducks actually reduce total cooling air flow by 8%. You’re moving less air but achieving better cooling. Tony shrugs. It’s not about how much air. It’s about getting the air where it’s needed.

Those rear cylinders weren’t getting any air flow at all. The air was taking an easier path over the top of the cowling. The duct force the air to go where it doesn’t want to go naturally. But that violates the principle of minimizing flow restriction. No offense, sir, but I don’t know what that means. I just know that in plumbing, sometimes you need to restrict flow in one place to create pressure in another. It’s the same idea. The engineers spend days trying to optimize Tony’s design.

They try different duct diameters, different materials, different routing paths. Nothing works better than Tony’s original concept. Finally, on October 28th, 1944, Colonel Lameé approves emergency implementation. Boeing receives the technical drawings on October 30th. By November 15th, they’ve retoled their production line to include the cooling ducts, now officially designated Validor bypass cooling system, in technical manuals, though crews will simply call them Tony ducks. November 24th, 1944. Saipan, Mariana Islands. The first B29s equipped with Tony’s modification arrive in the Pacific theater.

They’re assigned to the 73rd Bombardment Wing Hin Bomber Command under General Curtis Lame’s direct command. Captain Robert Fitzgerald pilots B-29 City of Los Angeles on the first combat test of the modification, a bombing mission against the Musashino aircraft plant near Tokyo. Distance 3,000 m round trip. Time at high power settings approximately 9 hours. The mission profile is a nightmare for engine cooling, long overwater flight, high altitude climb to 32,000 ft, sustained cruise power for hours, the perfect scenario for engine overheating.

Fitzgerald’s flight engineer, technical sergeant Mike Romano, monitors the engine instruments obsessively. Before the modification, number three engine right inboard was always the first to show temperature problems. Romano has three engine fires in his log book. He knows the warning signs. Rear cylinder temperature climbing above 550°, oil pressure starting to fluctuate, exhaust gas temperature spiking. 2 hours into the mission, number three’s rear cylinder gauge reads 438°. Front cylinders 421 degrees. Romano checks the gauge again. Taps it. Checks the circuit breaker.

Captain, I think we got a faulty temp gauge on number three. What’s it reading? Rear cylinders showing 438. That’s impossible. We’ve been at cruise power for 2 hours. Fitzgerald glances at his own instruments. All other engines are showing normal. You think number three is actually running hot and the gauge is lying to us? No, sir. I think it’s actually running cool, but that doesn’t make sense. They continue the mission. 9 hours total. The longest Fitzgerald has ever kept a B29 at sustained high power.

Number three engine never exceeds 455° on the rear cylinders. When they land back at Saipan, Romano inspects the engine. No signs of heat stress, no discoloration. The cooling fins look like they just came out of the factory. He finds the crew chief. What’s different about number three? New cooling mod. Some mechanic invented it. They’re calling them Tony ducks. Over the next 3 weeks, the data pours in. Premodification. September October 1944. B29 engine fires per 100 flight hours.

4.2 Two engines requiring early replacement due to thermal damage. 18% engine related mission aborts. 31% post modification. December 1944 February 1945. B29 engine fires per 100 flight hours. 0.7 engines requiring early replacement due to thermal damage. 3% engine related mission aborts. 6% the modification reduces engine fires by 83%. By March 1945, Boeing has retrofitted over 2100 B29s with a Validor cooling system. Wright Aeronautical incorporates it into all new R3350 engines coming off the production line. The impact is staggering.

Before the modification, the 20th Air Force was losing approximately 22 B29s per month to engine fires and related mechanical failures. after the modification, four per month. Conservative estimate, Tony Validor’s cooling ducks saved 216 B29s over the final 12 months of the war at 11 crew members per aircraft. That’s two 376 American lives, but the broader impact is strategic. With reliable engines, B29s can maintain the bombing campaign against Japan without interruption. the firebombing of Tokyo, the destruction of Japanese war industries, ultimately the atomic bomb.

Missions to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, none of it happens without B29s that can fly 3,000mi missions without their engines catching fire. From the Japanese perspective, after the war, captured Japanese Army Air Force documents reveal their assessment of the B-29 threat. Lieutenant General Torisiro Kowab, Deputy Chief of the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff, writes in his diary, “In autumn 1944, we believed the B29 program was failing. Their engines were unreliable. Our intelligence indicated high mechanical loss rates. We calculated that the Americans could not sustain operations.

Then in December 1944, everything changed. The B29s came in greater numbers. They flew longer missions. Their engines no longer failed over our territory. We realized we had lost the air war. A Japanese fighter pilot, Captain Saburro Sakai, later recalls, “We feared the B29 not because of its weapons, but because of its reliability. Earlier in 1944, we would sometimes see them lose engines, fall behind formations, become vulnerable. After late 1944, they flew in perfect formation for hours. Their engines never stopped.

We knew we could not win against such machines. Tony Validor’s simple solution saved thousands of lives and changed the course of the war. If this story has moved you, hit that like button right now and share this video with someone who loves history. These untold stories deserve to be remembered. Let’s make sure they are. June 1945, Wrightfield, Dayton, Ohio. The war in Europe is over. Japan is weeks from surrender. Tony Validor is being processed for discharge, heading back to civilian life.

Before he leaves, they try to give him a medal. The Army Commenation Medal for technical innovation that significantly contributed to the war effort. Tony refuses it. I didn’t do anything special, he tells the colonel, trying to pin the metal on him. I just fixed a cooling problem. That’s what mechanics do. Sergeant, your modification saved over 200 aircraft and thousands of lives. Then give the medal to the crews who flew the missions. They’re the heroes. I just installed some aluminum pipes.

The colonel is stunned. You don’t understand what you did, sir. With respect, I understand perfectly. The engineers figured out how to build the engine. The pilots figured out how to fly it. I figured out how to keep it cool. We all did our jobs. That’s all. Tony returns to Cleveland, goes back to plumbing, never mentions his war work to clients. In 1947, a reporter from the Cleveland plane dealer discovers the story. A local plumber who saved the B29 program.

The reporter wants to write a feature article. Tony declines the interview. I don’t want publicity. I did my job. That’s all there is to it. The reporter writes the article anyway, but without Tony’s cooperation. The headline reads, “Cleveland plumbers simple idea solved B29 crisis.” The article runs on page seven. Few people notice the technical legacy. Tony Validor’s bypass cooling concept becomes standard practice in aircraft engine design. Modern turboan engines use sophisticated versions of the same principle, dedicated cooling ducts that route air flow where it’s needed rather than relying on natural circulation.

The Prattton Whitney F-135 engine that powers the F-35 Lightning 2 uses advanced bypass cooling. The General Electric GE9X, the world’s most powerful jet engine, incorporates bypass cooling principles in its thermal management system. Aviation engineers call it directed cooling or forced path cooling. They don’t call it the validor system because history forgot Tony’s name. But the principle remains when fluid won’t flow naturally where you need it, create a dedicated path. It’s plumbing, pure and simple. Production numbers. Total B29s built 3,970 B29s lost to enemy action in G2.

147 B29s lost to engine fires, mechanical failure, premodification. 267 estimated B29s saved by Validor cooling system. 216 estimated crew lives saved. Two 376 R3350 engines produced with Validor modification. over 18,000 modern application. Today, every aircraft with air cooled engines uses descendants of Tony’s cooling principle. From Cessna 172s to Boeing 787s, the concept of dedicated cooling paths is fundamental to engine thermal management. NASA’s thermal management systems for spacecraft use similar bypass cooling principles. The International Space Station’s cooling loops employ directed flow cooling that Tony would recognize immediately.

Tony Validor died in 1982 at age 76, still working as a plumber. His obituary in the Cleveland plane dealer mentioned that he served as an aircraft mechanic during World War II. It made no mention of the B29 program, no mention of 2,76 lives saved. At his funeral, one mourner stood quietly in the back, a man in his 60s who nobody recognized. After the service, he approached Tony’s son. I flew B29s in the Pacific, 35 missions. My crew came home because our engines didn’t catch fire.

I didn’t know your father personally, but I’ve spent 40 years trying to find the mechanic who invented those cooling ducks. I wanted to thank him. Tony’s son was confused. My father never said anything about inventing anything. He always said he was just a plumber. The veteran smiled sadly. That sounds like the kind of man who’d save 2,000 lives and never think it was a big deal. The final word. Sometimes the greatest innovations don’t come from experts with advanced degrees.

Sometimes they come from someone who spent 15 years running pipes through Cleveland basement and understood one simple truth. Flow takes the path of least resistance. If you need flow somewhere else, build it a better path. Tony Validor wasn’t a genius. He wasn’t a hero. He was a plumber who looked at an aircraft engine and saw a plumbing problem and that made all the.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.