How One GM “Diesel Engine” Outsmarted Every Plane on the Battlefield

Picture this. It’s 1943 and a P38 Lightning screams across the Pacific at 25,000 ft. The pilot spots a formation of Japanese zeros below. He pushes the throttles forward and two Allison V1710 engines respond instantly, generating 3,200 combined horsepower. The Lightning dives at over 500 mph, faster than any zero can match.

In seconds, he’s behind them. Twin engines purring in perfect synchronization. This wasn’t supposed to happen. The engine powering this moment of aerial supremacy started life as something completely different, a diesel power plant for tanks. How did General Motors accidentally create one of the most important aircraft engines of World War II? How did a design everyone dismissed as inferior help win the air war? This is the story of the Allison V1710, the only American designed V12 combat engine of the war, and how it proved that sometimes the underdog wins by

playing a completely different game. The year was 1929. The Great Depression was about to hit, but nobody knew that yet. The US Army Airore had a problem. They were still flying biplanes with engines that belonged in a museum. The Curtis D12, their primary liquid cooled engine, was already obsolete.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, Rolls-Royce was developing what would become the Merlin. BMW was perfecting their inline engines. The Germans were secretly building the Dameler Benz DB600 series. America was falling behind and falling behind fast. Enter James Allison, founder of Allison Engineering Company in Indianapolis.

His company had been building race car parts and marine engines since 1915. They’d built the Liberty L12 engine during World War I under license, but Allison died in 1928, and his company was floundering. General Motors saw an opportunity and bought the company in 1929. The timing couldn’t have been worse. Or maybe it was perfect.

The Navy had just canled a contract for a new diesel engine. Allison’s engineers, led by a brilliant but stubborn man named Ronald Hazen, looked at those diesel blueprints and saw something else. They saw the foundation for an aircraft engine. Not just any aircraft engine, a 1,000 horsepower monster that could be mass-roduced using automotive techniques.

The army thought they were insane. a converted diesel design competing with purpose-built aircraft engines. But they gave Allison a chance anyway. The company received a contract for one experimental engine in 1930. Budget $25,000. That’s about $425,000 in today’s money. Rolls-Royce was spending 10 times that on the Merlin. Here’s where it gets interesting.

Hazen didn’t try to outenineer Rolls-Royce. He couldn’t. Instead, he applied Detroit automotive thinking to aircraft engine design. Make it simple. Make it reliable. Make it so any mechanic with basic training can fix it. Make thousands of them fast and cheap. The initial design was revolutionary in its simplicity.

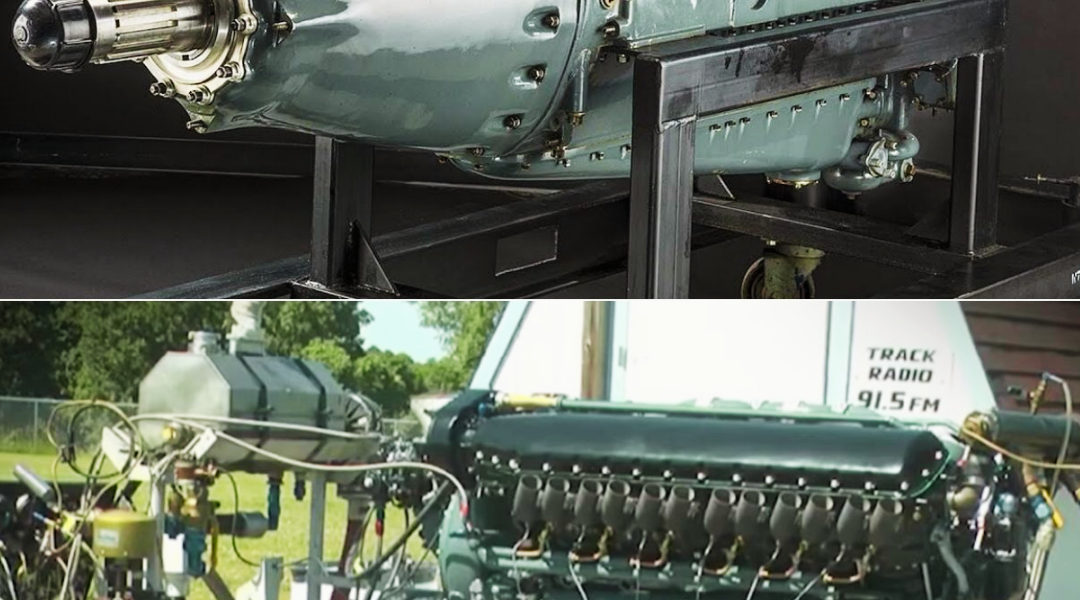

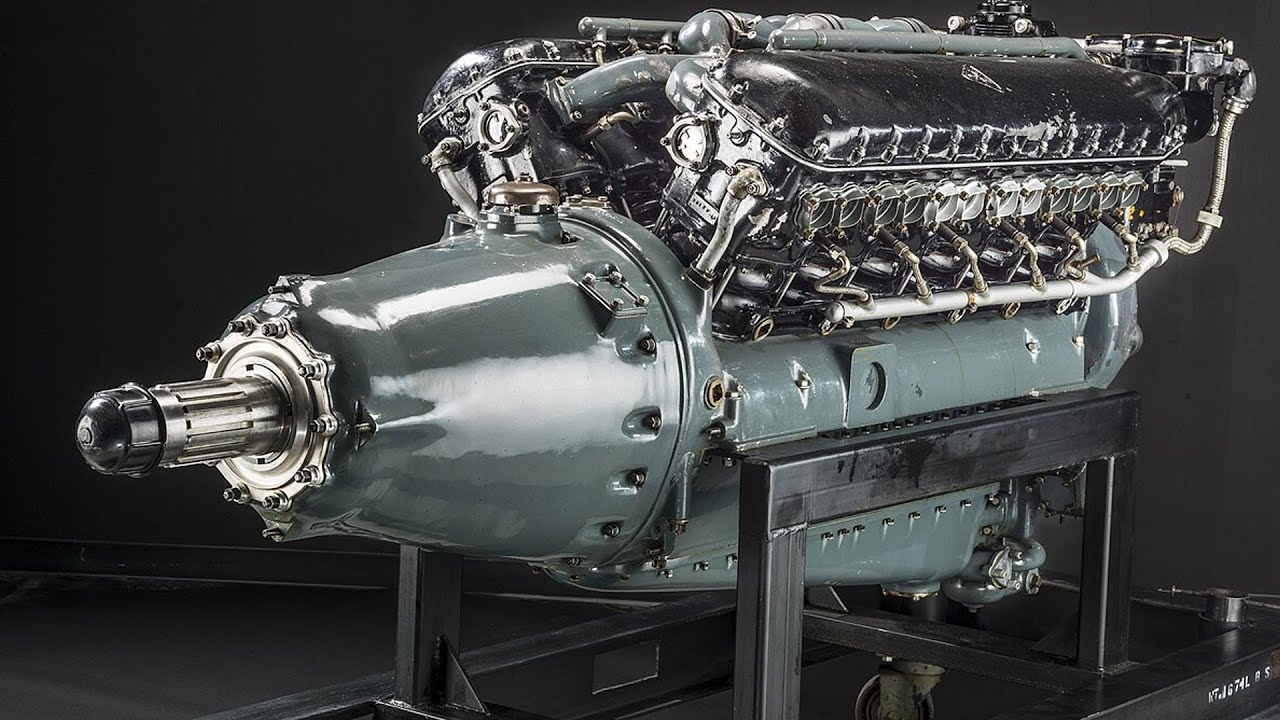

The V1710 used a 60° V angle, not the 45° most V12s used. Why? Because 60° balanced better. Less vibration meant longer engine life. The bore was 5.5 in stroke 6 in giving a displacement of 1,710 cubic in, hence the name. That’s 28 L for those keeping track. Massive by modern standards. The compression ratio was conservative at 6 5:1.

The Merlin ran 7:1. The DB 601 pushed 7.2:1, 2:1, but lower compression meant the Allison could run on 100 octane fuel when others needed 115 or even 130 octane. In wartime, fuel quality mattered as much as engine performance. The valve train was deliberately simple. Single overhead cams per bank, two valves per cylinder.

The Merlin used four valves per cylinder, more complex, more powerful, more things to break. The Allison philosophy, make it work, make it last, make 10,000 of them. The first V1710 ran on a test stand in 1931. It produced 650 horsepower and immediately threw a connecting rod through the crank case. The engineers went back to work.

The second attempt managed 750 horsepower before destroying itself. The Army observers weren’t impressed. Pratt and Whitney’s radial engines were already reliable. Wright Aeronautical was producing proven designs. Why waste time on this experimental V12? But GM had deep pockets and a point to prove. They poured money into the project.

By 1932, the V1710C model was producing 1,000 horsepower reliably. It weighed 1310 lb, giving a powertoweight ratio of 0.76 horsepower per pound. The contemporary Rolls-Royce Kestrel managed 0.46. The Allison was aluminum where others used the steel. It featured a forged aluminum crank case, cast aluminum cylinder heads, and steel cylinder liners.

The crankshaft was forged from chrome nickel malibdinum steel, heat treated and balanced to perfection. The real innovation was the supercharger. Every high alitude engine needs forced induction. The air gets thin up there. The Merlin used a two-speed, two-stage supercharger, complex but effective. The Allison used a single stage, singlese unit, simple, reliable, but limited.

This would become both its greatestweakness and surprisingly its secret weapon. The army finally paid attention in 1935. They needed a new pursuit plane engine. The Allison competed against the Continental IRV 1430 and the Pratt and Whitney R1830 radial. The tests were brutal. 150 hour endurance runs at full power.

Temperature extremes from minus40 to plus 120° F. Vibration tests that shook engines apart. The Allison survived everything. The army ordered 1,000 engines in 1939. Then Hitler invaded Poland. Suddenly, America needed fighters, lots of them. The problem was which fighters? The Curtis P40 Warhawk was first.

Curtis had designed it around the Allison from the start. The marriage was perfect. The V171033 produced 140 horsepower at sea level, pushing the P40 to 360 mph. Not spectacular, but good enough. The engine sat in the nose, driving a threeblade Curtis electric propeller through a 2.1 reduction gear. Cooling came from a radiator under the nose, giving the P40 its distinctive sharkmouth appearance.

But here’s what mattered. The Allison was reliable. In the African desert, where sand destroyed Merlin engines, the Allison kept running. Its air filters were better. Its tolerances were looser, not sloppier, but designed for realworld conditions. A P40 could belly land in the desert, get dug out, have its air filter cleaned, and fly again.

Try that with a Spitfire. Then came the Lockheed P38 Lightning. This was different, revolutionary. Twin engines, twin booms, a central NL for the pilot. Lockheed’s Kelly Johnson, the same genius who would later design the SR71, wanted turbo supercharged Allison’s, not mechanical superchargers like everyone else used.

Turbo superchargers driven by exhaust gases. The army said it was too complex, Johnson insisted. The result was magic. The P38’s V171049 engines were essentially the same as the P40s, but the turbo superchargers changed everything. At 25,000 ft, where the P40’s engine gasped for air, the P38’s turbos compressed that thin atmosphere back to sea level pressure.

The engines produced 150 horsepower each at altitude. The P-38 could fight at 30,000 ft, higher than most enemies could even reach. The turbo system was complex, intercoolers, waste gates, control systems, but it worked. The exhaust driven turbine could spin at 24,000 RPM. The compressed air was heated to over 300° F, then cooled by intercoolers before entering the engine.

This wasn’t just engineering, it was art. Let me explain exactly how this turbo system worked because it’s crucial to understanding the Allison success. Hot exhaust gases at 1,500° F rushed out of the engine at tremendous velocity. These gases spun a turbine wheel made from incanel, a nickel chromium superalloy that could withstand the heat.

This turbine was connected by a shaft to a centrifugal compressor on the intake side. As the turbine spun up to 24,000 RPM, the compressor forced air into the engine at up to 50 in of mercury, almost double atmospheric pressure. More air meant more fuel could be burned, which meant more power, which created more exhaust to spin the turbo faster.

It was a beautiful self-reinforcing cycle. The intercooler was equally important. Compressed air gets hot. Basic physics. The P38’s intercoolers used ram air to cool the intake charge from 300° down to near ambient temperature. Cooler air is denser, meaning even more oxygen per cubic inch.

This cooling added another 10% to the engine’s power output. The whole system was controlled by a waste gate, a valve that bypassed exhaust around the turbine to prevent overboosting. The pilot had a lever in the cockpit to control boost pressure, pull it back for cruise, push it forward for combat power. The numbers tell the story.

A naturally aspirated Allison produced 140 horsepower at sea level, but only 780 at 15,000 ft. With a mechanical supercharger like in the P40, it maintained 40 horsepower up to about 12,000 ft. But the turbo supercharged version in the P38, it produced 150 horsepower at 25,000 ft. At 30,000 ft, where a Messor Schmidt BF 109’s engine was down to 65% power, the P38 was still producing 90%.

The P38 became the Army Air Force’s primary long range fighter. Its range was extraordinary, 2,600 m with drop tanks. It could escort bombers all the way to Berlin and back. The top American aces in the Pacific, Richard Bong with 40 kills, Thomas Maguire with 38, flew P38s. Their Allison engines never let them down.

But the real test came with an aircraft nobody expected. The North American P-51 Mustang. North American aviation designed the P-51 in just 117 days. The British needed fighters desperately and NDLA promised something revolutionary. The early P-51s used the Allison V171039 producing 150 horsepower. The aircraft was beautiful laminer flow wings, perfect streamlining, a radiator design that actually produced thrust.

At low altitude, it was magnificent. The Allison powered P-51A could reach 390 mph at 5,000 ft, faster than a Spitfire or BF 109. But above 15,000 ft,performance fell off dramatically. The single stage supercharger couldn’t cope with altitude. The British had an idea. What if they put a Merlin engine in the P-51? The Packard Motor Company was building Merlin under license in Detroit.

In late 1942, they installed a Packard V1650, essentially a Merlin with American accessories in a P-51. The transformation was incredible. The two-stage supercharged Merlin gave the P-51D490 horsepower at 25,000 ft. Top speed jumped to 440 mph. The P-51D became the best fighter of the war. This looked like defeat for the Allison, but here’s the thing. It wasn’t.

The Allison had done exactly what it was designed to do. It proved that American mass production techniques could build reliable combat engines. Packard built 55,523 Merlin engines during the war. Allison. They built 69 to 305 V1710s, more than any other American aircraft engine except the Pratt and Whitney R1830 radial.

The Allison powered more than just fighters. The Bellp39 Araco Cobra used a V1710 mounted behind the pilot, driving the propeller through a long drive shaft. Weird design, but the Soviets loved them. They received 4,619 P39s through lend lease. Soviet ace Alexander Pushkin scored 47 of his 59 kills in P39s.

The engine placement gave the P-39 neutral handling, perfect for lowaltitude dog fighting on the Eastern Front. The P63 King Cobra was the P39’s bigger brother. Same midenine layout, but with a V171093 producing 1,325 horsepower. The Soviets received 2,397 of them. They used them as tank busters. The Allison’s reliability, perfect for ground attack missions.

One Soviet pilot reportedly flew his P63 through a barn to escape German fighters. The engine kept running despite ingesting hay and chickens. But the Allison’s greatest contribution might have been what it taught American industry. GM’s automotive approach, modular design, interchangeable parts, assembly line production revolutionized aircraft engine manufacturing.

A Rolls-Royce Merlin required skilled craftsman handfitting parts. An Allison could be assembled by workers with minimal training. Parts were truly interchangeable. You could take a crankshaft from engine number 100 and install it in engine number 50,000 without modification. The production techniques were revolutionary.

Allison pioneered the use of production line boring machines that could hold tolerances to 01 in. They developed new heat treatment processes that increased crankshaft life by 300%. They created modular subasssemblies, complete cylinder banks that could be pre-built and tested, then installed as units. This modularity had tactical advantages.

In the field, mechanics could swap entire cylinder banks in hours, not days. A P38 squadron in New Guinea reportedly kept a 90% availability rate despite operating from jungle strips with no proper facilities. Try that with handfitted British engines. The metallurgy was equally innovative. Allison developed new aluminum alloys specifically for the V1710.

The crank case used 195T6 aluminum heat treated for maximum strength. The connecting rods were forged from SAP 4140 steel chrome malibdinum alloy that could handle 15,000 lbs of tension per square in. The exhaust valves used sodium cooling hollow stems filled with metallic sodium that melted at operating temperature, transferring heat from the valve head to the stem.

This prevented valve burning, a common failure in high-performance engines. The sodium sloshed around inside the hollow valve stem as it moved, carrying heat away from the critical valve head area. Let’s talk about the engineering philosophy that made this work. Ronald Hazen, the V1710’s chief designer, believed in what he called design reserve.

Every component was stronger than it needed to be. The crankshaft could handle what was 800 horsepower even though the engine was rated for 150. The connecting rods were tested to 2,000 horsepower. This overengineering meant the engine could be pushed hard without failing. Late war versions like the V1710119 produced 1,600 horsepower reliably.

Some experimental versions hit 2,000 horsepower before grenading. The engine had growth potential built in from day one. The fuel system was remarkably sophisticated. The Bendix pressure carburetor eliminated the float chamber that plagued other engines during aerobatic maneuvers. It injected fuel based on mass air flow, not ventury vacuum.

This meant the engine wouldn’t cut out during negative G maneuvers. A P38 pilot could push the stick forward, diving inverted, and both engines would keep running smoothly. Try that in an early Spitfire, and the Merlin would cut out immediately. The ignition system used two centill magnetos per engine, each firing one of two spark plugs per cylinder, complete redundancy.

If one magneto failed, the engine kept running. If one plug fouled, the other kept firing. The magnetos were pressurized to prevent altitude related arcing. They could generate a 20,000 volt spark at40,000 ft where the air was so thin a normal ignition system would fail. Cooling was always the Achilles heel of liquid cooled engines.

One bullet through a coolant line and you had maybe 5 minutes before the engine seized. The Allison addressed this with multiple innovations. The coolant passages were designed with deliberate restrictions that limited flow if a line was cut. The engine could run for up to 15 minutes with a damaged cooling system.

Enough time to get home or at least away from enemy territory. The oil system was equally robust. Dry sump lubrication meant oil was stored in a separate tank, not the crankase. This allowed the engine to operate at extreme angles without oil starvation. The oil pump could deliver 90 gall per minute at 90 PSI.

The oil cooler used fuel as a heat exchange medium, warming the fuel for better combustion while cooling the oil. Every drop of heat energy was recycled. But here’s what really set the Allison apart. Production quality control. Every single engine was test run for 5 hours at the factory. Not just a sample from each batch. Every engine.

The first hour at idle, checking for leaks and unusual noises. The second hour cycling through power settings. The third hour at cruise power. The fourth alternating between idle and maximum power every 5 minutes. Thermal cycling that revealed any weaknesses. The fifth hour at full combat power.

If an engine survived this torture, it was shipped. If not, it was completely rebuilt. The test stands were engineering marvels themselves. Allison built 100 test cells, each capable of testing engines at simulated altitudes up to 30,000 ft. They could replicate temperatures from -70 to + 150° F. The dynamometers could absorb 2,000 horsepower continuously.

The data collection system recorded 50 different parameters every second. temperatures, pressures, vibration frequencies, fuel flow, oil consumption. This data went back to the design engineers, creating a feedback loop that constantly improved the engine. The human element mattered, too. Allison employed 23,000 workers at peak production in 1943. Many were women.

Allison’s angels, they called themselves. They built 1,000 engines per month, every month, for three years straight. The quality never wavered. Rejection rate stayed below 1%. That’s better than modern automotive engine production. The logistics were staggering. Each V1710 contained 7,000 individual parts. Allison’s supply chain included 100 subcontractors across 33 states.

Crankshafts came from Canton Drop Forge in Ohio. Bearings from New Departure in Connecticut. Magnetos from Cintilla in New York. Everything had to arrive just in time in perfect condition to maintain production flow. They never missed a delivery date, not once in six years of war production.

Now, let’s address the elephant in the room. Altitude performance. Yes, the single stage supercharged Allison struggled above 15,000 ft. But this wasn’t a design failure. It was a design choice. The Army Airore doctrine in the 1930s emphasized lowaltitude tactical support. They didn’t think fighters would operate above 20,000 ft.

The Allison was optimized for this requirement. When doctrine changed and high altitude performance became critical, the turbo supercharged versions proved the basic engine was sound. The problem wasn’t the Allison. It was the supercharger choice. Allison knew this. They developed the V1710E series with an auxiliary supercharger, essentially a two-stage system like the Merlin.

The V17101 produced 1,500 horsepower at 25,000 ft. But by then, the war was ending and jets were the future. Only 1,000 E-series engines were built. They powered late model P82 twin Mustangs, proving the Allison could match any piston engine in existence when properly supercharged. The combat record speaks for itself.

P38 Lightnings shot down more Japanese aircraft than any other fighter. The top American ace in Europe, Gabby Gabeski, started his 28 kill streak in a P40. The Flying Tigers turned the Allison powered P40 into a legend, shooting down 297 Japanese aircraft while losing only 50. The Soviets loved their P39 so much they requested them specifically over newer designs.

But numbers don’t tell the whole story. Listen to the pilots. Robin Olds, who flew P-38s before transitioning to P-51s, said the Lightning was the most honest airplane he ever flew. It told you exactly what it was doing through the controls. That was the Allison’s smooth power delivery. No sudden surges or dead spots, just linear, predictable thrust.

Chuck Joerger started his combat career in a P39. He credited the Allison’s reliability with teaching him to trust his equipment. crucial when he later broke the sound barrier. The maintenance crews had their own perspective. Tech Sergeant William Culvert, who maintained P38s in Italy, wrote, “Those Allison’s were like clockwork.

Change the oil every 50 hours. Clean the filters. Check the magnetos. They just ran. We hadengines with 500 combat hours that still made book power. Try that with a Merlin or a DB 605.” The Allison’s influence extended beyond military aviation. After the war, thousands of surplus V1710s hit the civilian market.

They powered unlimited hydroplanes to 200 mph speeds. They set land speed records at Bonavville. They powered the most radical hot rods of the 1950s. A guy named Art Arons bolted a V1710 to a tractor chassis and set a landspeed record of 413 mph in 1960. But the real legacy was industrial. The Allison proved that America could mass-produce complex machinery at unprecedented scale and quality.

The production techniques developed for the V1710 influenced everything from car engines to jet turbines. The modular design philosophy became standard in aerospace. The quality control procedures became the foundation for modern six sigma manufacturing. General Motors investment paid off in unexpected ways.

The expertise gained from the V1710 program led directly to the Detroit diesel engine family. The same engineers who perfected aircraft engine manufacturing applied those lessons to truck engines. The aluminum casting techniques pioneered for the Allison influenced the small block Chevrolet V8. The precision machining capabilities built for wartime production revolutionized peacetime automotive manufacturing.

The turbocharger development was equally influential. The P38’s turbo installation taught American engineers how to manage ultra high-speed turbo machinery. This knowledge fed directly into early jet engine development. Many of the engineers who worked on P38 turbo systems went on to develop America’s first production jet engines.

The turbine metallurgy bearing technology and high temperature materials all crossed over. Let’s look at one specific innovation. The master rod assembly in the V1710. One connecting rod in each bank was the master with the other five slave rods attached to it. This design, borrowed from radial engines, eliminated the need for a forked rod arrangement.

It simplified production and improved balance. This concept influenced opposed piston diesel designs and even modern high-performance automotive engines. The Allison’s pressure lubrication system was revolutionary for its time. Oil pressure was maintained at 8590 PSI even at idle. Compare that to contemporary automotive engines running 3040 PSI.

This high pressure ensured positive lubrication to every bearing surface even under extreme G loads. The oil jets that cooled the pistons from underneath became standard in high performance engines. You’ll find similar systems in modern Formula 1 engines. Consider the economic impact.

The V1710 program cost General Motors approximately $75 million in development, about 1.3 billion in today’s money. But the government contracts totaled 7 to25 million wartime dollars. The profit margin was deliberately kept low, about 8%. But the volume made up for it. More importantly, GM gained expertise that couldn’t be bought.

They became a major defense contractor, a position they maintain today. The Allison story also demonstrates the importance of industrial base. When war came, America had the factory capacity, the machine tools, the skilled workers, and the organizational knowledge to produce engines at scale. Germany built about 42,000 DB 601605 engines during the entire war.

Japan managed 13,000 Nakajima Sakai engines. America built 69305 Allison’s plus 55523 Packard Merlin’s plus 173,618 Pratt and Whitney radials. Production capacity won the air war as much as engineering excellence. But perhaps the most important lesson is about design philosophy. The Allison wasn’t the most powerful engine.

It wasn’t the most advanced. It wasn’t the most efficient. But it was the most producable, the most maintainable, and the most adaptable. It could be built by workers without extensive training. It could be maintained by mechanics with basic tools. It could be modified for different applications without complete redesign. This philosophy, call it democratic engineering, influenced American industrial design for decades.

Make it good enough, make it reliable, make it in vast quantities. It’s the same thinking that created the Liberty ship, the Sherman tank, the Jeep. Not the best in any category, but good enough in every category and available in overwhelming numbers. The V1710’s end came quickly. Jets made piston engines obsolete almost overnight.

The last production V1710 rolled off the line in 1948. Total production, 69,35 engines. But Allison didn’t disappear. They transitioned to turborops and jets, becoming a leader in helicopter turbines and eventually part of Rolls-Royce. The company that started with a converted diesel design became one of the world’s premier gas turbine manufacturers.

Today, only a few hundred V1710s survive. Most are in museums, silent reminders of industrial warfare. A handful still fly in restored warb birds. At air shows, you can hear thatdistinctive Allison sound. Smoother than a Merlin, less harsh than a Dameler Benz. It’s the sound of American mass production meeting aviation excellence.

The Allison V1710 story teaches us that engineering success isn’t always about building the best. Sometimes it’s about building the right thing at the right time in the right quantity. It’s about understanding your constraints and optimizing within them. It’s about production engineering being just as important as design engineering.

When we look back at World War II aviation, we celebrate the glamorous fighters and their pilots. But behind every P-38 Lightning that swept the Pacific, behind every P40 that defended Egypt, behind every P39 that fought on the Eastern Front, there was an Allison V1710 built in Indianapolis by former car mechanics and housewives.

Designed to be good enough, reliable enough, and numerous enough to win a global war. The V1710 never achieved the fame of the Merlin. It doesn’t have the mystique of German engineering or the romance of British craftsmanship, but it did something perhaps more important. It proved that American industrial democracy could produce excellence at scale.

It showed that with the right philosophy, the right processes, and the right people, you could turn a failed diesel design into an engine that helped win a war. In the end, the Allison V1710 wasn’t just an engine. It was a statement of industrial capability. It was proof that America could take a simple idea, build thousands of good engines instead of hundreds of perfect ones and execute it flawlessly.

Every one of those 69 to 305 engines represented American workers doing precision work at unprecedented speed. Every successful combat mission proved that mass production didn’t mean inferior quality. The next time you see a P38 at an air show, listen to those Allisonens. That smooth rumble isn’t just exhaust noise.

It’s the echo of American industrial might. It’s the sound of democratic engineering triumphing over autocratic perfectionism. It’s the voice of an engine that started as a diesel, became a legend, and proved that sometimes the underdog wins by playing a completely different game. What do you think about the Allison V1710’s place in aviation history? Was it truly inferior to the Merlin or just different? Drop your thoughts in the comments below and don’t forget to subscribe for more deep dives into the engines that changed history.