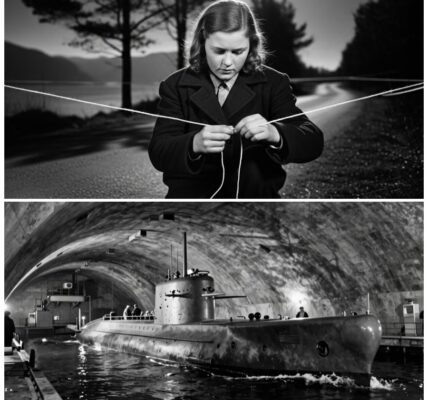

How One 16-Year-Old Girl’s Laundry Line Signals Warned Americans of German Ambushes.NU.

How One 16-Year-Old Girl’s Laundry Line Signals Warned Americans of German Ambushes

Part 1 — The Clothesline That Talked

Stavelot, Belgium. December 19th, 1944.

Morning came in gray and hard, the kind of light that didn’t warm anything. Frost clung to the edges of the garden beds behind the Dubois farmhouse, making the soil look like it had been dusted with salt. The temperature hovered just above freezing, and every breath Marie took showed up as a small cloud in the air before it vanished.

Marie Dubois was sixteen years old and doing something ordinary.

She was hanging laundry.

A sheet went up first, stiff from cold, snapping faintly in the wind when she shook it out. Then a smaller item, then another. Her hands moved with practiced routine, the way a girl learns to move when she’s lived in the same house long enough to know every post, every knot in the rope, every place the line sagged if you hung something too heavy.

Survival in a place like this depended on ordinary routines.

You kept your head down.

You kept moving.

You didn’t stare at soldiers.

You didn’t ask questions.

You didn’t become memorable.

Because being memorable in a war zone was one step away from being dead.

Less than three kilometers away, German forces were regrouping after their initial advance through the Ardennes.

Less than three kilometers away in the other direction, American troops had established defensive positions along the western edge of the village.

And Marie—like most civilians caught in this frozen corner of Belgium—believed that the only goal was to live long enough to see the armies move on.

She had no idea that within forty-eight hours, her laundry line would become a warning system.

Not by accident.

By design.

And by the end of that week, dozens of American soldiers would still be breathing because a teenage girl had decided that cloth could speak.

The Farmhouse Between Two Armies

Marie lived with her grandmother, Celestine, in a two-story stone farmhouse that had belonged to their family for four generations.

Her parents were in Brussels. They’d sent Marie out to the countryside eighteen months earlier, believing it would be safer than the capital.

Safer. That word had always sounded reasonable until you lived through war long enough to understand that war doesn’t respect geography.

Marie’s father worked in a textile factory that had been converted into something the German war effort could use. Marie’s mother helped care for wounded civilians in what used to be a school building before the windows were blown out and the desks became stretchers.

Marie hadn’t seen them since August. A brief letter had arrived through a neighbor traveling on “official business,” which meant a man carrying papers the Germans stamped and therefore a man who didn’t get searched too carefully.

It had been one page.

A few lines.

We are alive.

We love you.

Stay with Grandmother.

The farmhouse sat on slightly elevated ground, with a clear view across the Amblève River valley.

It was positioned almost perfectly between German positions to the east and the American defensive line to the west.

If you were cruel, you’d call it strategic.

If you were honest, you’d call it unlucky.

The Americans at the Door

The first American soldiers Marie encountered were three men from the First Infantry Division who appeared at the farmhouse door on the afternoon of December 17th.

They didn’t kick the door down. They didn’t threaten. They looked like men who hadn’t slept and didn’t fully trust the world.

They asked in broken French if Marie had seen German troop movements.

Celestine invited them inside immediately, insisting they were too thin to stand outside in the cold. She offered what little bread and cheese remained.

Marie watched the soldiers carefully.

One of them—youngest of the three—could speak enough French to communicate. He introduced himself as Corporal William Chen from San Francisco, California, and Marie noticed how his eyes moved constantly, cataloging the room, the windows, the exits, the corners.

His voice was polite. His posture said he expected violence.

The sergeant, Frank Morrison from Nebraska, was broad-shouldered and tense, glancing toward the windows like he could feel danger in the glass.

The third soldier, Private Thompson, could not have been more than eighteen. His hands trembled slightly around the cup of ersatz coffee Celestine had made from roasted barley and chicory.

They explained their situation.

They were part of a unit trying to delay the German advance until reinforcements could arrive. They had about sixty men spread across defensive positions covering nearly two kilometers of front.

Sixty men facing several hundred Germans, possibly more.

They needed warning. They needed eyes.

Because traditional reconnaissance was becoming dangerous. German patrols were aggressive and desperate, and the forest swallowed men whole.

Celestine listened quietly, her old face unreadable.

Marie listened too, and something in her shifted.

Not bravery.

Not heroism.

Something colder.

A recognition that the war had landed on her doorstep whether she wanted it or not.

After the soldiers left, Marie stood at her bedroom window and watched distant artillery flashes on the eastern horizon.

She could hear the low rumble of engines moving along roads beyond the forest.

Her grandmother came to stand beside her, placing a weathered hand on her shoulder.

Celestine spoke softly.

“I remember when your grandfather watched from this same window in the last war,” she said. “He used to say knowledge is a weapon… if you know how to deliver it.”

Marie turned to her.

“What do you mean?”

Celestine went to the wooden chest at the foot of Marie’s bed. She opened it and pulled out a carefully folded piece of cloth.

She unfolded it.

A large white sheet, yellowed with age.

“In 1914,” Celestine said, “people used signals. Sheets on a line meant all clear. Colored cloth meant danger. Different arrangements meant different messages.”

Marie held the sheet, feeling worn cotton between her fingers.

She thought about the American soldiers—thin, spread out, blind to what was happening in the village, waiting to be surprised.

And she realized something that felt like a spark.

The clothesline behind their house was visible from the western ridge.

Visible to anyone watching with binoculars.

Visible in a way that didn’t require radios or couriers or risky night travel.

Visible and innocent.

Laundry was one thing the Germans didn’t question.

Laundry didn’t look like resistance.

Laundry looked like life.

And life was supposed to continue even under occupation.

The First Signal

Marie didn’t sleep much that night.

She lay awake listening to distant gunfire and thinking in patterns.

If one sheet meant “normal,” then two could mean “patrols.”

If red meant danger, then her grandmother’s red tablecloth could mean attack.

Blue blanket could mean vehicles.

Left to right could mean direction of movement.

It wasn’t elegant.

It didn’t need to be.

It just needed to be consistent enough that someone smart on the American side might notice.

The next morning, December 19th, Marie went out deliberately at 8:00 a.m. and hung laundry.

Not just to dry.

To speak.

One white sheet meant no immediate danger.

Two white sheets meant German patrols active in town.

If she added the red tablecloth, it meant troops massing for an operation.

Blue blanket meant vehicles.

Placement meant direction.

She had no way to tell the Americans she’d built this system.

So she made the system visible and hoped that observant eyes would eventually decode it.

For three days, nothing happened.

No American came to the farmhouse.

No note appeared.

No sign that anyone had noticed.

Marie kept hanging laundry anyway, varying it according to what she observed.

German soldiers occupied the town hall and several larger buildings. Patrols moved through streets at irregular intervals. Marie learned to time her own movements, to appear purposeful but unremarkable.

She watched from windows.

She listened in the market.

She counted trucks.

She memorized officer faces.

And every morning, she spoke through cloth.

December 22nd

On the fourth day—December 22nd—Marie saw something different.

German trucks arrived before dawn.

Troops assembled in the square near the church.

She counted forty soldiers. They formed into squads, checked equipment, moved with urgency that meant more than routine.

Her grandmother watched from the kitchen window, lips pressed tight.

Marie didn’t hesitate.

She went to the garden and hung two white sheets… and the red tablecloth.

She placed the items so that anyone watching from the west would know:

German force gathering. Operation imminent. Moving west.

That afternoon, Corporal Chen returned alone.

He looked exhausted. Dark circles under his eyes. His uniform carried the dirt of days without proper rest.

Celestine insisted he sit. Poured more barley coffee. Offered bread.

Chen spoke quietly in French.

“We have been watching your clothes line,” he said.

Marie froze.

Chen continued, voice careful, almost reverent, like he was afraid to break something fragile.

“My sergeant noticed a pattern. Different items. Different arrangements. We think… maybe you are trying to tell us something.”

Marie felt relief hit so hard it was almost nausea.

She nodded slowly.

Then she walked to the window and pointed toward the town hall.

“Forty soldiers arrived this morning,” she said. “They are preparing for an operation. I put the red cloth to warn you.”

Chen moved to the window, binoculars lifting automatically.

“How did you know what to signal?” he asked.

“I guessed what you needed,” Marie said. “I watched what happened and tried to show you.”

Chen turned toward her with something like wonder.

“You created a code,” he said. “Without training. Without knowing if we would understand.”

He pulled a small notebook from his pocket.

“Alright,” he said, “teach me.”

And for the next hour, Marie and Corporal Chen did something quietly extraordinary in that farmhouse:

They turned laundry into intelligence.

One sheet: patrols under ten.

Two sheets: ten to thirty.

Three sheets: larger formation.

Red tablecloth: attack preparation.

Blue blanket: vehicles.

A yellow curtain: officers present.

Placement: direction.

Absence: danger to Marie herself—meaning she was watched or compromised.

Chen wrote it all down.

Then he pressed something into Marie’s hand before leaving.

A small silver compass, worn but functional.

“If you need to leave quickly,” he said, “head west-northwest. Five kilometers. Ask for Captain Robert Miller. Tell him William Chen sent you.”

Marie closed her fingers around the compass.

“What happens if the Germans discover what I’m doing?” she asked.

Chen’s expression hardened.

“You must be very careful,” he said. “What you are doing is extraordinarily dangerous.”

Then, softer:

“But it’s also extraordinarily important. You are saving lives.”

When he left, Marie stood in the garden staring at the clothesline.

It looked innocent.

It looked like a household chore.

But she understood now what it had become:

A voice calling across frozen fields.

A warning system stitched from cotton and courage.

Part 2 — Christmas Eve on the Line

By December 23rd, Marie’s hands were chapped raw from cold, but she still went out every morning at eight.

Not because she had that much laundry.

Because routine was the camouflage.

If she only hung cloth when danger was near, it would become a signal anyone could notice. But if she hung something every day—sheet, pillowcase, curtain, apron—then the line looked like what it was supposed to look like.

A girl doing chores.

A grandmother keeping a household alive.

Nothing to see here.

That was the genius of it. Not the code itself—codes are easy to invent. The genius was hiding the code inside behavior so ordinary that even enemy soldiers stopped seeing it.

The Germans in Stavelot didn’t think in terms of laundry.

They thought in terms of rifles, radios, men in forests.

They searched for resistance where resistance “looked like” resistance.

Marie didn’t look like anything.

She looked like a farm girl with cold fingers.

And that invisibility kept her alive for long enough to matter.

The White Cloth on the Fence

After Chen left that afternoon, Marie’s stomach stayed tight with a strange mixture of fear and relief.

Fear, because now she knew for sure the Americans were watching. That meant the Germans could watch too.

Relief, because now she wasn’t whispering into empty air. Someone could hear her.

That night she barely slept. She kept thinking of the compass in her pocket, the way it felt like a promise and a threat at the same time.

At dawn, she went to the garden again. Same hour. Same movements. Same line.

And then she saw it.

A small white cloth tied to a fence post far out on the western edge of the valley—barely visible, but there. A signal from the Americans.

Celestine noticed too. She didn’t smile. She didn’t celebrate.

She just nodded once, as if confirming something she’d already known.

“They see you,” her grandmother said quietly.

Marie’s throat tightened.

They see.

That was all she needed.

The Night Before Christmas

December 24th arrived with a brittle silence that felt unnatural.

No birds.

No distant farm noises.

Just the low hum of engines somewhere beyond the village and the constant pressure of cold.

Marie woke before dawn to the sound that now lived in her bones: vehicles.

Not one.

Many.

She crept to her bedroom window and looked down toward the village square.

What she saw made her scalp tighten.

The German garrison wasn’t just patrolling.

It was assembling.

The square near the church was full of movement—men forming into groups, officers walking between them, pointing, organizing. Trucks idled with their lights covered. Two armored vehicles sat like dark shapes, engines rumbling. The Germans moved with purpose.

This was not a “probe.”

This was not a patrol.

This was an attack.

Marie counted quickly, heart hammering.

Not forty this time.

At least one hundred.

Maybe more.

She could barely see faces in the darkness, but the mass of bodies was unmistakable.

She heard a barked order in German drift up from the street.

Then boots moved as one.

They were going west.

Toward the American line.

Marie’s hands went cold.

For a half-second she froze in the window, pinned by the knowledge of what would happen if she did nothing.

American positions were thin.

They needed time.

Not hours.

Minutes.

Minutes meant men could get into place, machine guns aligned, fields of fire set.

Minutes meant survival.

Marie pulled on a coat and stepped into the morning dark.

The garden was slick with frost. Her breath came fast, visible and loud in the quiet air.

She glanced toward the town hall and the streets.

Was anyone watching her?

She couldn’t tell.

She didn’t have time to tell.

She grabbed the laundry basket and moved with speed that felt reckless.

Three white sheets.

Red tablecloth.

Blue blanket.

She hung them in the pattern Chen had written down.

Three sheets: large formation.

Red: attack imminent.

Blue: vehicles involved.

And she placed them so the direction was unmistakable—east to west.

Toward the Americans.

Her fingers shook so badly she fumbled a clothespin and it snapped into the dirt.

For a moment she thought she might vomit from fear.

Then she forced herself to move normally, to walk back inside as if she’d done nothing but hang laundry.

Because the most dangerous moment wasn’t the signal.

It was what your body did after the signal—how it revealed panic.

Marie shut the door and leaned her back against it, listening.

Outside, the engines rose.

The German column began moving.

“Full Assault”

Three kilometers away, Corporal William Chen stood in an observation post on the western ridge with binoculars pressed to his face.

He hadn’t slept much either.

None of them had.

Their defensive line was thin enough that every rumor felt like a death sentence. Every night felt like it might be the one night the Germans broke through.

Chen watched the Dubois farmhouse because it was the one reliable thing left in their sector.

In a war full of uncertainty, Marie’s laundry line had become something rare:

A clock.

A signal.

A voice.

When the first gray light gave him enough visibility, Chen’s stomach dropped.

He could make out the shapes clearly now.

Three white sheets.

The red cloth.

The blue blanket.

The arrangement screamed at him like a siren.

Chen didn’t hesitate.

He spun and ran down toward the command post where Sergeant Frank Morrison was crouched beside a small fire, trying to keep his hands warm without letting the smoke give away their position.

“Morrison!” Chen shouted, breath bursting out white. “Full assault. Large force with vehicles. Coming now.”

Morrison moved like a man whose body had been trained by years of violence.

Orders came out of him sharp and fast.

“Positions! Wake everybody! Machine gun teams—set crossfire on the main approach! No one fires until I say!”

Men scrambled, boots slipping on frozen ground as they ran to foxholes and stone buildings. Ammunition was checked. Grenades were pulled into reachable pockets. Rifles were loaded. The machine gun teams dragged their weapons into place, setting overlapping fields of fire exactly as they’d practiced.

In less than four minutes, the Americans in that sector were ready.

Not relaxed.

Not confident.

But ready.

And ready was the difference between holding and breaking.

The Attack Hits the Line

The German assault began exactly as Marie’s line had warned.

Troops advanced across open ground in textbook formation, supported by two armored vehicles pushing behind them. Their plan relied on surprise and weight—hit thin American positions before they could coordinate.

But there was no surprise.

The American line was awake.

Waiting.

The Germans moved closer, boots crunching through frozen grass, their breath visible in the pale dawn.

Sergeant Morrison held his hand up, steady, watching through binoculars.

Hold.

Hold.

Hold.

The Germans were close enough now that their faces were not just shapes.

Close enough that American bullets would matter.

“NOW!” Morrison shouted.

American fire opened like a door slamming shut.

Machine guns stitched the approach with brutal precision. Rifles cracked in rapid rhythm. The two machine gun teams created overlapping coverage that made the open ground a trap.

German soldiers dropped, scrambled for cover, confused by resistance they hadn’t expected to be this organized, this immediate.

The armored vehicles tried to push forward, but the Americans had positioned their heavier weapons for exactly that. The first vehicle took hits and backed off. The second hesitated, then tried to flank, but the terrain forced it back toward the kill zone.

The first assault wave faltered.

Then a second wave pushed forward—heavier, angrier.

The Germans weren’t amateurs. They adjusted quickly. They spread out. They fired suppressing bursts.

But the Americans had the advantage of prepared positions and warning. They weren’t being surprised into chaos. They were already locked into their defense.

The fight lasted nearly three hours.

Three hours of freezing gunfire and smoke and men screaming in languages that sounded the same when they were dying.

Marie didn’t see the battle directly from her house—not clearly.

But she heard it.

The dull thunder of machine guns.

The sharper cracks of rifles.

The occasional heavier boom.

She and Celestine stayed in the cellar, hands clasped, listening to the war move like an animal above them.

Marie’s mind kept returning to the clothesline.

Had they seen it?

Had it worked?

Had she hung everything correctly?

The battle ended as suddenly as it began.

The gunfire faded.

Then silence.

A kind of silence that didn’t feel peaceful.

It felt like the moment after a storm when you step outside and see what the wind left behind.

The Germans withdrew back toward the village, leaving casualties in the open ground. They hadn’t achieved their objective.

The American line held.

In that one sector—thin and vulnerable—it held.

And dozens of men were alive because Marie Dubois had turned laundry into warning.

The Thank You That Felt Dangerous

That evening, as Marie hung ordinary laundry in fading light, she saw Chen approaching across the field, accompanied by an older officer.

This man had the bearing of command. He wore captain’s insignia and moved like someone who’d been deciding life and death for too long.

Chen introduced him.

“Captain Robert Miller,” Chen said.

Miller stepped closer, face tired but eyes sharp.

“Miss Dubois,” he said through Chen’s translation, “what you did this morning saved at least twenty of my men.”

Marie swallowed.

The words hit her harder than she expected.

Saved.

Not “helped.”

Saved.

“Your warning gave us the time we needed,” Miller continued. “Without it, we would’ve been overwhelmed.”

He paused, then added something quieter.

“We came to thank you. And to ask if you’re willing to continue.”

Marie looked at Miller, then at Chen, then back toward her grandmother standing in the farmhouse doorway.

Celestine’s face was pale with fear—but her eyes were steady.

She nodded slowly.

Marie felt the weight of it settle into her chest.

If she continued, she risked her life.

If she stopped, she risked American lives.

There wasn’t a clean choice.

There was only the choice she could live with.

“I will continue,” Marie said.

“As long as I can help, I will continue.”

Miller nodded once.

No speeches.

No medals.

Just a soldier acknowledging a civilian’s courage the way a soldier should.

When the Germans Start Looking

The problem with success is that it creates attention.

And attention is what killed resistance fighters.

In the days after Christmas Eve, German patrol activity increased. Officers were angry. They didn’t understand how their assault had been anticipated so precisely.

They began looking for leaks.

For informants.

For patterns.

Marie kept signaling, but now every cloth she hung felt heavier, as if the rope itself had become a noose.

On January 7th, the danger sharpened.

A German officer—Major Klaus Weber, veteran of the Eastern Front—noticed Marie’s routine.

He didn’t stop her.

He didn’t accuse her.

He watched.

From a concealed position.

For hours.

He studied how methodically she arranged items, how her eyes kept flicking toward the western ridge.

Weber didn’t need proof.

He had instinct.

He assigned two soldiers to monitor the farmhouse continuously.

For three days, Marie could not safely signal.

She maintained routine—simple, innocent-looking laundry.

Only white sheets.

Nothing that screamed pattern.

And the absence of real warning meant the Americans had to operate blind, relying on their own dangerous reconnaissance.

Marie felt sick with frustration.

She could see German patrols moving.

She could see shifts in activity.

But she couldn’t speak through cloth without exposing herself.

On the fourth day, the surveillance broke.

A German patrol got into a firefight near the river. Casualties were dragged back to the village. Weber was called away. His attention shifted.

Marie seized the opening.

She hung a complex signal—one that didn’t just report troop movement, but reported that she had been watched.

It was the most dangerous message she’d ever sent.

And that night, Chen returned, moving through darkness with the care of a man who knew one wrong sound could end a civilian’s life.

“You were compromised,” he told her quietly.

Marie nodded.

“I know.”

Chen’s face was grave.

“We’re planning an operation,” he said. “Limited push. Clear German forces out of the village within the week. If we can do that, it lowers the immediate threat to you.”

Marie looked past him toward the dark village.

“And until then?”

Chen didn’t sugarcoat it.

“Until then, you have to be careful enough to survive.”

Then he gave her something new.

American intelligence had made contact with Belgian resistance. They’d established a courier network.

If Marie could get information to a contact in a neighboring village eight kilometers away—a baker named Anton Merier—then her intelligence could reach American headquarters in detail, not just through cloth patterns.

It was a step up.

It was also a step deeper into danger.

Marie listened and felt her stomach tighten.

A clothesline was risky.

A courier run was lethal.

But she nodded anyway.

Because now she understood something about courage:

It doesn’t show up when you feel brave.

It shows up when you feel afraid and move anyway.

Part 3 — The Basket That Carried a Battlefield

By the time Chen told Marie about the courier network, the clothesline no longer felt like a clever trick.

It felt like a fuse.

It worked because it was quiet.

It worked because it was ordinary.

But now the Germans were looking.

And once an occupying army starts looking at ordinary things, ordinary things stop being safe.

Marie understood that immediately.

A clothesline signal could be denied.

Explained away.

“I wash. I dry. I live.”

A courier run couldn’t.

A courier run meant intent.

A courier run meant movement beyond routine.

A courier run meant a girl crossing frozen fields with information that could kill men.

And in a war, the difference between “innocent” and “dead” is often just whether someone believes your story.

Chen gave her the details as carefully as if he were handing her a live grenade.

A baker in the neighboring village—Anton Merier.

Eight kilometers away.

The back door.

A recognition phrase she had to memorize.

No paper in her pockets.

No visible nervousness.

If she was stopped, she was just bringing food to family.

Nothing more.

Marie listened, fingers wrapped around the compass Chen had given her days earlier.

She didn’t ask if it was too dangerous.

She didn’t ask if there was another option.

Because the truth was simple:

If she didn’t do it, someone else would have to.

And someone else might not know the roads like she did.

Might not know how to look harmless.

Might not know when to stop breathing so soldiers didn’t hear panic in your voice.

That night, Celestine sat at the kitchen table mending a sock.

She didn’t look up when Marie said, “I have to go tomorrow.”

The needle paused.

Celestine’s hands stayed steady.

“What kind of go?” she asked quietly.

Marie swallowed.

“The kind you don’t want me to.”

Celestine finally looked up then, eyes sharp as glass.

For a moment, Marie thought her grandmother might forbid it.

But Celestine didn’t live inside illusions anymore.

She had survived one war already.

She knew what the world demanded when it broke.

Celestine stood and opened a cupboard.

She pulled down a basket—old wicker, familiar, used for eggs and bread and vegetables for as long as Marie could remember.

Then she set it on the table.

“Then we make you look like you’re going to market,” Celestine said.

Marie felt her throat tighten.

It wasn’t permission.

It was partnership.

The False Bottom

The resistance contact—Anton Merier—needed more than cloth signals could provide.

The Americans needed details: troop positions, strength estimates, equipment, morale, supply status.

Things Marie had been collecting in her head for weeks.

Now she had to put them on paper.

Paper was dangerous.

Paper made thought permanent.

Paper could hang you.

Marie and Celestine worked by candlelight.

Celestine drew a thin wooden panel from the old chest in Marie’s bedroom—something her grandfather had used decades ago, a spare board that fit perfectly into the bottom of the basket.

They lined it with cloth.

Marie wrote her notes in tiny handwriting, dense and careful, leaving no wasted space.

Simple sketches.

A hand-drawn map of the village with German-occupied buildings marked.

Approximate troop counts.

Patrol timing.

Where the trucks parked.

Which roads they favored.

Which officers seemed confident, which looked nervous.

Then they folded the pages tight and slid them beneath the false bottom.

On top, Celestine placed eggs and a small wheel of cheese.

Ordinary.

Believable.

Marie practiced her story out loud.

“My aunt is ill.”

Celestine corrected her tone.

Less nervous.

More annoyed.

Annoyance reads as honesty in occupied territories.

A frightened girl gets searched.

A mildly irritated girl delivering food? That’s just life.

Before dawn, Marie left.

The world was still dark, snow crunching under her boots, the air so cold it burned the inside of her nose.

She carried the basket on her arm like she’d done a hundred times.

She forced her breathing slow.

Steady.

Like it was just another errand.

Her heart didn’t believe the act.

Her body did it anyway.

Two Hides in the Frost

The route to the neighboring village wasn’t a road.

Roads were watched.

Roads were where German trucks moved, where patrols walked, where checkpoints appeared overnight like sores.

Marie took field paths and forest edges, moving through places she’d known since childhood—places she’d once walked for berries and now walked for survival.

Twice she had to hide.

The first time was in a ditch near the treeline when she heard voices ahead.

German voices.

Boots.

Laughter.

Two soldiers walked past smoking, talking about something Marie couldn’t quite catch.

She held her breath until her lungs screamed.

The basket pressed into her ribs.

The eggs didn’t crack.

The soldiers didn’t look down.

They passed without noticing the girl frozen in the ditch like she’d been born there.

The second time was worse.

A patrol—four men—crossed the path she needed. Not far away, close enough she could see their breath, hear their boots on frozen ground.

Marie slipped behind a haystack, crouched low, praying the basket didn’t rustle.

One of the soldiers stopped and turned his head slightly, like he’d heard something.

Marie’s pulse slammed in her ears so loud she was sure he could hear it.

Then a gust of wind rattled dry stalks in the field.

The soldier shrugged.

Kept walking.

Marie stayed hidden another full minute after they were gone, because you never trust the first absence.

Then she moved again.

The Stop

Near the edge of the neighboring village, a single German soldier stood at an informal checkpoint—a rifle slung, coat collar turned up, posture bored but alert.

Marie’s stomach dropped.

He hadn’t been there yesterday.

New checkpoints appeared like that in wartime—random, arbitrary, and deadly.

Marie forced herself to keep walking.

She didn’t speed up.

Speed looks guilty.

She didn’t slow down.

Slowing looks guilty too.

She walked like a girl with a task and no time for nonsense.

The soldier stepped into her path.

“Wohin?” he asked. Where are you going?

Marie swallowed and switched to the halting German she’d practiced.

“To my aunt,” she said, lifting the basket slightly. “She is ill. I bring food.”

The soldier’s eyes flicked to the eggs, the cheese.

He looked at Marie’s face.

Sixteen. Thin. Cold. Not threatening.

He could have searched the basket.

If he lifted the false bottom, everything ended.

Marie met his eyes with a mild irritation she didn’t fully feel but could imitate.

“She has fever,” Marie added. “I must go.”

The soldier hesitated.

He looked young. Not much older than Chen, maybe. He looked tired in a way that didn’t belong to victors.

Then he waved her on.

“Geh,” he muttered. Go.

Marie kept walking.

She didn’t allow herself to breathe until she was around the corner and out of sight.

Then she exhaled shakily, tears stinging her eyes from cold and adrenaline.

She hadn’t realized until that moment how close she’d been to dying.

The Bakery Door

Anton Merier’s bakery sat on the main street.

At this hour, it looked closed—shutters half-drawn, windows dark.

Marie didn’t go in the front.

Chen had been clear.

She went around back.

A small door. Weathered wood. A faint smell of flour and yeast even through the cold.

She knocked once.

Then again.

The door opened a crack.

A stocky man with flour-dusted hands and cautious eyes looked her over.

Marie spoke the recognition phrase Chen had taught her.

Not dramatic.

Quiet.

Casual.

Like a customer making a comment about the weather.

Anton’s eyes softened slightly, just enough to confirm she’d said the right thing.

He opened the door fully and let her in.

Inside, warmth hit her like a wave.

Bread smell.

Real bread smell.

For a second, Marie’s stomach clenched with hunger.

Then she remembered why she was there.

Anton took the basket without comment, moved to a back counter, lifted the false bottom in one smooth motion.

He slid the papers out and tucked them into a ledger as if that was where they belonged.

Then he replaced the false bottom, placed fresh bread on top, and handed the basket back.

The entire exchange took less than two minutes.

Anton met her eyes once.

“Courage,” he said softly in French.

Marie didn’t answer.

If she answered, she might cry.

She turned and left.

Back into the cold.

Back into danger.

Back toward the farmhouse.

The Maps That Became a Plan

Marie didn’t see what her information did on the American side, not immediately.

But she felt the shift.

Within days, German movements near the village started meeting resistance in a way they hadn’t before.

American patrols moved with more certainty.

They were less surprised.

Less reactive.

More prepared.

Chen came by at dusk and tied the small white cloth to the fence post again.

Received.

Understood.

And then a second cloth appeared the next day—an acknowledgment that felt almost like praise.

Marie didn’t smile.

She just kept working.

Because the danger didn’t stop.

If anything, it tightened.

The Germans were still angry about their failed Christmas Eve assault. They were still hunting for leaks. They still suspected the village.

But now the Americans had something they hadn’t had before:

A clear picture.

A map drawn from civilian eyes.

January 21st

The operation to clear the village came at dawn on January 21st.

Marie and Celestine heard it before they saw it.

Artillery.

Not distant.

Close enough to shake dust from the cellar ceiling.

The house groaned with each concussive impact.

Celestine grabbed Marie’s hand and pulled her down the cellar stairs.

They huddled in the cold, damp darkness as the world above them turned violent.

The fighting lasted most of the day.

It wasn’t one clean battle.

It was street-to-street confusion.

Gunfire echoing between stone walls.

Shouts.

Crashes.

The sound of men dying on cobblestones.

Marie pressed her hands to her ears at one point, not because she was fragile, but because the noise was too much—the kind of noise that makes you feel like the whole world has become nothing but impact.

At dusk, the fighting faded.

Silence returned, thick and uncertain.

Footsteps approached the farmhouse.

Celestine stiffened.

Marie held her breath.

Then a voice in French called out:

“Madame Dubois? It’s the Americans.”

Celestine exhaled shakily.

They climbed upstairs.

The kitchen windows were cracked.

Dust covered everything.

But the house still stood.

Outside, American soldiers moved through the yard, consolidating control.

Captain Robert Miller appeared at the door, helmet under his arm, face smeared with dirt and exhaustion.

He looked at Marie like he was seeing her clearly for the first time—not just as a civilian, not just as a girl with laundry, but as someone who had been part of the fight.

“Miss Dubois,” he said, voice thick. “Your intelligence was crucial today. Your maps saved my men from walking blind into ambush positions.”

Marie’s knees felt weak.

She hadn’t been on the ridge.

She hadn’t fired a rifle.

And yet he was telling her she had been part of it.

Celestine put an arm around her.

Proud and terrified at once.

“You did something remarkable,” Miller said quietly.

Marie could only nod.

Words felt too small.

The War Moves On

After the village was cleared, the front line shifted east.

Danger didn’t vanish overnight, but it receded.

Marie’s role diminished because her village was no longer contested ground.

Other civilians in other villages began doing similar work, guided by methods the Americans now understood—ordinary signals, simple patterns, invisible intelligence.

But Marie’s clothesline had been among the first in that sector.

And it had worked.

In late February, Chen came one last time.

He looked older than he had in December, as if winter had carved years into his face.

He handed Marie a letter.

Signed by Captain Miller and others.

Formal recognition of her contribution.

Marie held it carefully, as if paper could bruise.

Then Chen gave her a second gift—a small leather journal and a pen.

“You should write it down,” Chen said. “In your own words. Someday people will tell stories about generals and operations. But this—this matters too.”

Marie looked at him.

“What happens after?” she asked quietly. “After the war?”

Chen stared out toward the fields for a moment.

“I hope we learn,” he said. “But hope isn’t enough. It takes work. The kind of work you did. Quiet. Constant. Unnoticed.”

Marie nodded.

Because she understood that now.

Work doesn’t always look like glory.

Sometimes it looks like laundry.

Years Later

Marie wrote in that journal.

Not every day.

Not beautifully.

But honestly.

She wrote about fear.

About pretending to be ordinary while doing something dangerous.

About her grandmother’s steady hand.

About the moment Chen said, “We’ve been watching your clothesline,” and Marie realized her voice had reached someone.

After the war ended in May 1945, Marie returned to Brussels and reunited with her parents, both alive.

Her father had sabotaged production quietly.

Her mother had hidden people when she could.

When Marie told them what she’d done, her father was angry first—angry she’d taken such risk.

Then pride settled in behind it.

Because parents don’t like to discover their children have become people with courage beyond their control.

Decades later, Marie returned to Stavelot for a commemoration.

She stood in the garden looking at the clothesline frame still standing, weathered now, rope replaced countless times.

A young journalist asked her what she’d been thinking back then.

Marie answered simply:

“I was thinking about the next thing I had to do. Hang the laundry correctly. Watch carefully. Walk carefully. I did not think of myself as heroic.”

Chen—older now too—stood beside her and said:

“You taught me that intelligence is paying attention and sharing what you learn. Sometimes the simplest methods are the most effective because they’re the least expected.”

Marie never argued with him.

She only smiled.

Because in that winter, she learned a truth that lasted longer than war:

The ordinary can become a weapon if you choose it carefully.

And courage doesn’t always carry a gun.

Sometimes it carries clothespins.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.