How a US sniper killed 11 people in 4 days using a standard trick – and then failed for 78 days. US

How a US sniper killed 11 people in 4 days using a standard trick – and then failed for 78 days.

At 6:27 a.m. on March 14, 1944, Lieutenant John George crouched on a ridge overlooking the Hukong Valley in Burma. His Winchester Model 70 leaned against a moss-covered rock, his rifle aimed at a trail some 300 meters below, where Japanese patrols were making their way through the dawn light. He was 28 years old and had been the Illinois State Champion at the age of 23.

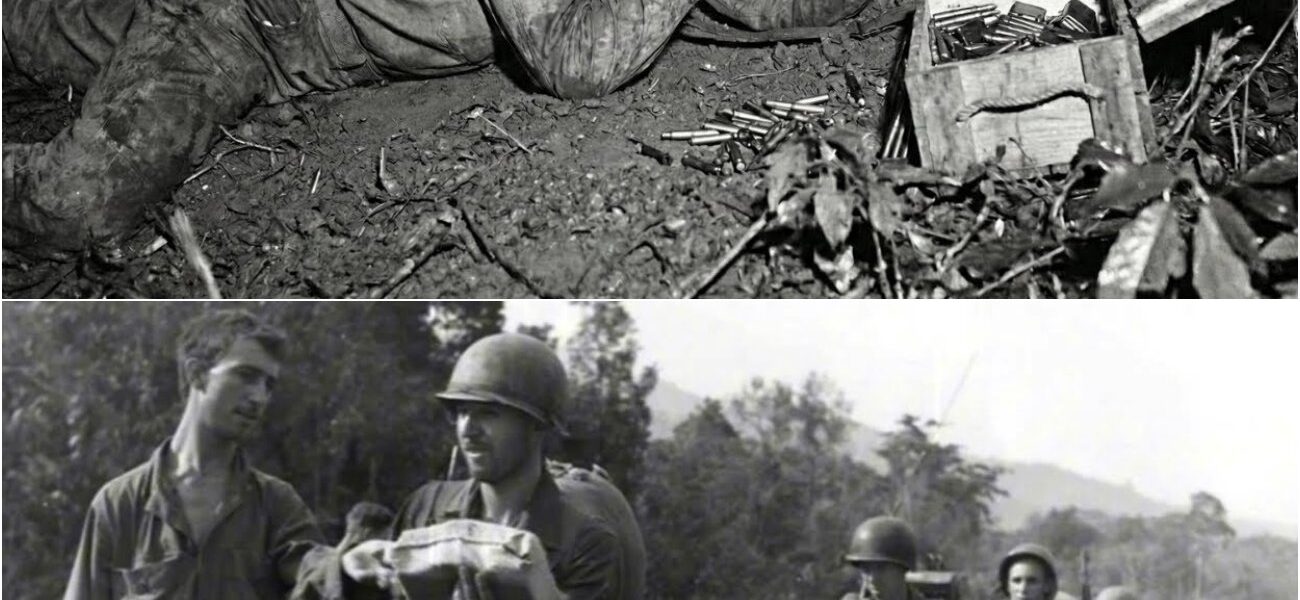

Guadal Canal: 11 Japanese snipers killed in 4 days with 12 shots. Burma: 28 days carrying the rifle through dense jungle; visibility never exceeded 50 meters. Not a single shot fired. The Winchester weighed 4 kg, making it lighter than the one used at Guadal Canal. George had removed the walnut stock and replaced it with a plastic one. This modification saved 400 g.

His backpack weighed 60 pounds. Ammunition, ten days’ worth of provisions, water, poncho, entrenching tools. Every gram counted when marching 20 meters a day through steep terrain where paths sank into mud and men collapsed from malaria as often as from enemy fire. But the rifle remained silent at the Guadal Canal. Other officers had dismissed the Winchester as a toy gun for male officers with civilian telescopic sights, while real soldiers carried Garands.

George proved them wrong. Eleven enemy snipers, four days, twelve shots. Now in Burma with Merrill’s Marauders, George lugged around a 4 kg bullet he couldn’t use. The Burmese jungle offered no solid bunkers, no clear line of sight through coconut palm groves, no time for precise shots at 220 meters through a Weaver 330C scope while the Japanese infantry maneuvered at close range.

In Burma, it was a war of movement. Forced marches of 32 kilometers, ambushes at 30 meters, followed by immediate retreat. A repeating rifle was useless, because the sheer volume of fire determined life and death. George would soon learn why the rifle that had dominated the Guadalajara Canal failed him in Burma. And when he finally fired, every shot would come at a price the death toll could never capture.

Twenty-eight days earlier, on February 15, 1944, George arrived in the USA after ten months, specifically at Fort Benning, Georgia, where he had been training officers. He taught men who had never heard a shot fired in combat how to operate the Guadalajara Canal. He explained to them how to spot Japanese snipers in trees and how to construct elevated firing positions.

How to conduct a boat operation without losing sight of the targeting optics. He then joined the 5.37th Mixed Unit. No official designation. The men called themselves Galahad or Merrill’s Raiders, after their commander, Brigadier General Frank Merrill. The mission was impossible by conventional standards.

A 500-meter march through northern Burma, terrain that Japanese commanders deemed impassable for forces larger than a company. No artillery support, no motorized transport, no established supply routes. 3,000 men, pack animals, and everything they could carry. Objective: capture the Mitkina airfield.

The airfield was crucial for Allied supply routes to China. Japanese forces controlled it with approximately 4,000 soldiers dug into defensive positions that had never been subjected to a frontal assault. George examined the Winchester rifle at Dali Barracks. The rifle had survived the Guadal Canal. It had been obsessively cleaned after being submerged in a water-filled crater during mortar fire.

Patches filled with preservatives and gun oil ran down the barrel until they came out white. But in Burma, everything was to be different. Patrols lasting for weeks. Each soldier carried 27 kg of equipment, ten days’ worth of provisions, ammunition, water, and personal gear. George calculated the weight. Winchester Model 70 with a walnut stock: 275 g. Weaver 330C scope: 340 g. Total weight: 4.7 kg.

The M1 Garand, which the other men carried, weighed 4.3 kg empty. The Garand was a semi-automatic rifle with an 8-round magazine. The Winchester was a bolt-action rifle with a 5-round magazine. The Garand was lighter and had a higher rate of fire in close combat. George found synthetic stock material in a supply depot. It was an experimental, fiberglass-reinforced polymer.

Weight 1.2 oz versus 2 lb with a walnut stock. Saving 14 oz. George fitted a synthetic stock, adjusted the scope’s eye relief, and tested 20 shots at an improvised shooting range. Groups of 4 inches at 300 yards. Acceptable deterioration considering the significant weight reduction. Final rifle weight: 8 lb 14 oz. Still heavier than a Garand, but 1.10 oz lighter than before.

On a three-month patrol carrying 27 kg of equipment through mountainous jungle, every gram determined whether they could remain operational or be evacuated medically. On February 24, 1944, 3,000 men began the march. George carried the Winchester rifle, 60 rounds of .30-06 ammunition in stripper clips, and 27 kg of equipment. In the first week, they covered 134 km through jungle so steep that they used ropes to descend from the ridges. A single misstep would have meant a 30-meter fall onto rocks, a fall that had claimed the lives of two of their backpackers.

The number of malaria cases increased daily. Daytime temperatures reached 35 degrees Celsius, nighttime 21 degrees. Humidity was 85%. It rained torrentially, turning paths into raging rivers and rendering the dry land a distant memory. George cleaned his Winchester rifle every evening. Preservative grease on the boat, an oilcloth wrapped around the scope. But he never fired. The battles were brief. Japanese patrols at a distance of 30 to 50 meters.

M1 Garens returned fire with semi-automatic weapons. Immediate movement after enemy contact to avoid a counterattack. No time for precise firing with bolt-action rifles. No static positions where a telescopic sight would have offered an advantage. March 14, 1944. After 19 days of marching, George had carried a rifle worth 814 ounces over 217 miles. Not a single shot fired.

The battalion had fought twelve times – skirmishes, ambushes, brief firefights followed by rapid retreats. Georges Winchester remained strapped to his backpack during the engagements. Like all officers, he carried an M1 Garand as his primary weapon. The marauders lost more men to disease than in combat: malaria, riots, typhus.

Medics distributed quinine, but supplies were rationed. Some men marched with such high fevers that their skin burned to the touch. They marched on, because stopping meant evacuation, and evacuation meant missing their destination. Of George’s platoon, only 23 men remained, down from 30; seven had been evacuated due to illness, none from combat wounds.

The Winchester remained silent. George carried an 814-ounce rifle, which proved more useful in camp than in action. March 23, 1944, 6:47 a.m. George’s platoon reached a ridge overlooking the Tani River. Width: approximately 80 meters. Current: moderate. Depth unknown, but according to intelligence assessments, fordable. Mission: Observe Japanese movements.

Report by radio. Attack only if tactically necessary. George positioned the platoon in cover 340 meters upstream from the suspected Japanese crossing point. Dense vegetation provided cover. We crossed a gap in the trees 412 meters to the opposite bank, where a path led out of the jungle.

George owned a pair of binoculars with sevenfold magnification, better than the Weaver rifle scope with 2.5x magnification, but you couldn’t kill with binoculars. George weighed the options. If Japanese troops were to cross the border during the day, the Winchester rifle would be useful. It allowed for long-range attacks without revealing the platoon’s position, but the likelihood of that was slim. The Japanese preferred night operations.

6:47 a.m. George observed the river through binoculars. Movement on the opposite bank. Japanese soldiers were positioning themselves to cross. No covert movement. Deliberate preparation. Approximately 30 to 40 men. George counted the officers. Three were identifiable by their katanas and binoculars. One officer was directing the troops, pointing, gesturing, and forming up the soldiers. Distance: 412 yards.

George lowered the binoculars and picked up the Winchester rifle. For the first time in 28 days, the rifle left its carrying position, ready for potential combat use. George cocked the rifle and aimed at the officer leading the troops. 412 yards. Light wind from the left and right. George adjusted the windage two clicks to the right. The officer stood still, concentrating on troop organization.

Perfect target under optimal conditions. George controlled his breathing. Three seconds in. Two seconds hold. Pull the trigger. Smooth as glass. 1.4 and 5.4 kg trigger pull. The Winchester recoiled. The bang echoed through the valley. 375 meters away. The Japanese officer tumbled. His body fell backward. The troops took cover. George cocked the rifle. The empty cartridge case was ejected.

A new round was loaded. He scanned for a second target. Nothing. The Japanese had taken cover. George lowered his rifle. Immediate problem. The report of the Winchester was unmistakable, unlike the sharp crack of the M1 Garin. Deeper, more resonant. George’s platoon leader appeared beside him. “Lieutenant, you heard that. You know the approximate position.”

George understood. A shot, a confirmed hit, but also a shot that could jeopardize the position. On Guadalajara, George operated alone. The risk to the position was irrelevant, as he could relocate quickly without having to coordinate troop movements. In Burma, George commanded 30 men. Moving 30 soldiers through the jungle was slow and noisy. Changing location took time.

The enemy could have exploited this. Result: The Japanese broke off the river crossing. Mission successful. However, the platoon had to be redeployed immediately. A two-mile march north to evade a possible Japanese counter-patrol. Thirty men, then 60 men each, through treacherous jungle. Two hours of marching time. George calculated the cost. A confirmed kill, bought with 60 man-hours of marching time and the potential risk to the platoon’s operational safety.

April 1944, weeks 6 to 8 of the campaign. George had fired his Winchester once in March. Not once in April. The battalion continued its advance. Over 400 miles were covered. Casualties mounted not from combat, but from attrition, malaria, insubordination, and exhaustion. The men marched half-conscious. The fever was so high that some lapsed into delirium, but they marched on, for halting meant being left behind and risking an uncertain evacuation.

By mid-April, the battalion’s strength had shrunk from its original 3,000 men to 2,200; 800 had been evacuated or killed. Only 23 men remained of George’s platoon; seven had died of disease, none in combat. Winchester remained silent. George carried a rifle with a final size of 814, which had proven more deadly in practice. April 17, second engagement.

George’s platoon was advancing through hilly terrain when a Japanese machine gun opened fire. It was a heavy 7mm Type 92 machine gun with a rate of fire of 450 rounds per minute. The position was about 380 meters ahead of the platoon on a rise. The machine gun held the platoon at bay. The return fire from the M1 Garands was ineffective. The distance was too great for accurate aiming.

George recognized the problem. The machine gun position offered a clear line of fire. The platoon couldn’t advance. A flanking maneuver was impossible. A stalemate. George took off his Winchester rifle. For the first time in three weeks. He positioned himself behind a large rock overhang. Distance: 380 yards. The target’s machine gun position was visible through the scope. George saw the muzzle flash and could determine the approximate position of the gunner. The wind was negligible.

George aimed. Calmed his breathing. Fired. The machine gun fell silent. George cocked the bolt. Loaded another round. Waited five, ten seconds. The machine gun didn’t fire again. Whether it was an attempt to kill or suppress the situation is unclear, but the position was neutralized. The problem of the characteristic bang returned. The Winchester’s bang echoed through the valley, unlike that of several M1 Garands firing simultaneously.

Corporal Williams from Ohio shouted, “Cease fire! Return to our own position!” Based on a distinctive bang, Williams believed the Japanese had captured an American rifle. Ten seconds of confusion ensued until the sergeant clarified. The problem: the Winchester rifle sounded too different. In the ensuing firefight with multiple weapons, the distinctive bang caused confusion among his own men. George’s realization.

Repeating rifles, with their characteristic sound, presented two crucial problems in mobile warfare. First, their low rate of fire hampered their effectiveness in suppressing enemy fire. Second, the distinctive bang caused confusion among friendly troops. In static positions like the Guadal Canal, these problems were manageable.

The mobile operations in Burma were a resounding failure. May 11, 1944, final approach to Mitakina. The battalion had covered over 1,100 kilometers. Destination: Mitakina airfield, 80 kilometers away. Effective strength had dwindled to only 1,400 men out of an original 3,000. George’s platoon, 19 men, had fired two shots with a Winchester machine gun in 77 days. An eight-man patrol under George’s command broke through the Japanese defensive ring.

Reconnaissance mission to the airfield. Distance 12 miles behind friendly lines. Deep penetration. The patrol spotted a Japanese position. A sniper was in an elevated position 290 yards away. He was holding an American patrol from another unit. The patrol had radioed for backup. George’s team was the nearest available unit.

George analyzed the situation. A Japanese sniper was operating from a hilltop with a clear view of the path where the American patrol was trapped. The sniper was systematically firing at targets. Distance: 290 meters, uphill. Moderate wind from left to right. George had a chance to shoot, but Winchester only had three rounds left in the magazine. George had already fired two shots; the magazine held five rounds, and he hadn’t reloaded stripper clips for three days, as he hadn’t expected to be used.

George took up his position. Winchester shouldered, scope aimed. Japanese sniper visible through the vegetation. Three clicks to the right to compensate for the wind. Calm breathing. Trigger pulled. The shot rang out. The Japanese sniper flinched, stumbled, and tumbled down the slope. George cocked the bolt. Last bullet in the chamber. He searched for a second target. None. Clear position.

Immediate result. The pinned patrol found no casualties among the rescued soldiers. George’s patrol withdrew. Mission accomplished. But Winchester had only one bullet left. Deep in Japanese territory, 19 kilometers from their own lines, George had a bolt-action rifle with only one cartridge, while the rest of the patrol carried an M1 Garin with an eight-round magazine capacity.

The retreat led 19 kilometers back to their own lines. The patrol encountered six Japanese soldiers at a distance of 40 meters. A firefight broke out. M1 Garens rifles fired semi-automatically. George fired the last shot of his Winchester. Whether the shot hit its target is unclear in the chaos. He dropped his rifle and drew his M1911 pistol. Caliber .45. Seven rounds.

The pistol proved more useful at a combat range of 15 meters than an empty repeating rifle. The patrol survived and reached their own lines. There were no casualties. Upon returning, George reloaded his Winchester with five fresh rounds, but the lesson had been learned. In 78 days, George had fired the Winchester only three times. The result: three confirmed or probable kills. During the same period, George fired an estimated 40 rounds with the M1 Garand in several engagements. The results are unknown, but the high rate of fire maintained the tactical initiative and kept the platoon’s fight going effectively.

On May 17, 1944, looters captured Mitkina airfield. The operation was a success; the strategic objective was achieved. Losses amounted to 2,900 men out of an original force of 3,000. Only 15 men remained from George’s platoon. In three months of continuous operations against enemy forces in the contested area, he had fired three shots with his Winchester rifle. George was evacuated in June, not because of a combat wound, but due to the effects of the three-month jungle operation: malaria.

George lost 18 kg of his original weight of 77 kg. The doctors at the field hospital determined that George needed rest. At least three months without combat. George’s war service was over for the time being. During his recovery, he analyzed the performance of his equipment. With his Winchester Model 70, he had killed eleven Japanese snipers at the Guadalajara Canal.

Static positions, unobstructed lines of sight, precise fire at long range. Burma required a different weapon, a semi-automatic for high rates of fire, not for precision fire from a boat. Future warfare would be mobile. The next war, if there was one, would require an M1 Garand or a better model, not a Winchester. The rifle that had dominated the Guadalajara Canal was obsolete for mobile operations in Burma.

Final Burma statistics. George achieved three confirmed kills with the Winchester; the number with the Garand and pistol is unknown. The battalion suffered 59 killed, 314 wounded, and 379 evacuated due to injury or illness. The Japanese estimated the dead at 800. Mitkina airfield was captured. Supply lines to China were secured. Strategic success. Individual marksmanship with the precision rifle was largely irrelevant to the operational success.

In July 1944, George returned to the United States, to Fort Benning, Georgia, where he was promoted to captain and took on training duties. He instructed infantry officers on the experiences of the Guadalajara Canal and Burma, but not in firing the Winchester rifle; rather, he focused on the tactics of the M1 Garand, its firepower, suppressive capabilities, and the doctrine of mobile warfare appropriate for modern combat conditions.

The fate of the Winchester. The rifle remained in George’s locker and was rarely used. The Pacific islands were recaptured one by one. The American armed forces advanced. The need for individual snipers with privately owned rifles decreased. The military standardized on mass production, interchangeable parts, and uniform equipment.

Winchester embodied the craftsmanship of bygone eras, individual skill, and a civilian approach to solving military problems. In 1947, George wrote “Shots Fired in Anger,” over 400 pages of technical descriptions of weapons, ammunition, ballistics, and tactics. The Guadalajara Canal was extensively documented. Burma is briefly mentioned. George wrote honestly.

Winchester had proven exceptional at the Guadalajara Canal, but only mediocre in Burma. Different terrain demanded different weapons. The book became a classic among gun enthusiasts. It is still available and continues to serve as a reference work on small arms in the Pacific War. Post-war life. George was discharged from military service in January 1947. Lieutenant Colonel, two Bronze Stars, Purple Heart, Combat Infantry Badge.

Princeton University, graduated with honors in 1950. Oxford, four years of political science studies. British East Africa, four years of regional institutional studies. Advisor and lecturer on African affairs at the U.S. State Department. Privately owned Winchester Model 70. Rarely mentioned in his professional life. Final resting place.

Winchester donated this rifle to the National Firearms Museum in Fairfax, Virginia. A display case with a plaque describes its history. Most visitors walk right past it without a second glance. It looks like an ordinary hunting rifle, but it isn’t. It’s the rifle with which a state marksman outshot professionally trained military snipers on the Guadalajara Canal.

A rifle that proved obsolete in Burma. A rifle for mobile warfare. The documented transition from the era of precision shooting to the semi-automatic fire doctrine that defined modern infantry combat. John George died on January 3, 2009, at the age of 90. Winchester outlived him; the rifle sits in the museum—a silent testament to the fact that exceptional weapons are not exceptional in every context.

Skills that excel on one battlefield can fail on another. In modern warfare, there is no longer room for craftsmanship when industrial firepower determines the outcome. The rifle that killed eleven enemy snipers in four days on Guadalajara fired only three times in 78 days in Burma. The same rifle, the same shooter, a different war. The Winchester Model 70 with a synthetic stock was George’s attempt to adapt the weapon to the new realities.

But no modification could change the fundamental truth. The precision of bolt-action rifles had given way to the firepower of semi-automatic rifles. The rifle wasn’t obsolete because it failed. It was obsolete because modern warfare exceeded the capabilities of a single shooter with a single rifle.

Note: Some content was created using artificial intelligence tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creative reasons and historical illustration.