- Homepage

- Uncategorized

- Germans Couldn’t Believe This “Invisible” Hunter — Until He Became Deadliest Night Ace. VD

Germans Couldn’t Believe This “Invisible” Hunter — Until He Became Deadliest Night Ace. VD

Germans Couldn’t Believe This “Invisible” Hunter — Until He Became Deadliest Night Ace

The engines began turning at 17:31 hours.

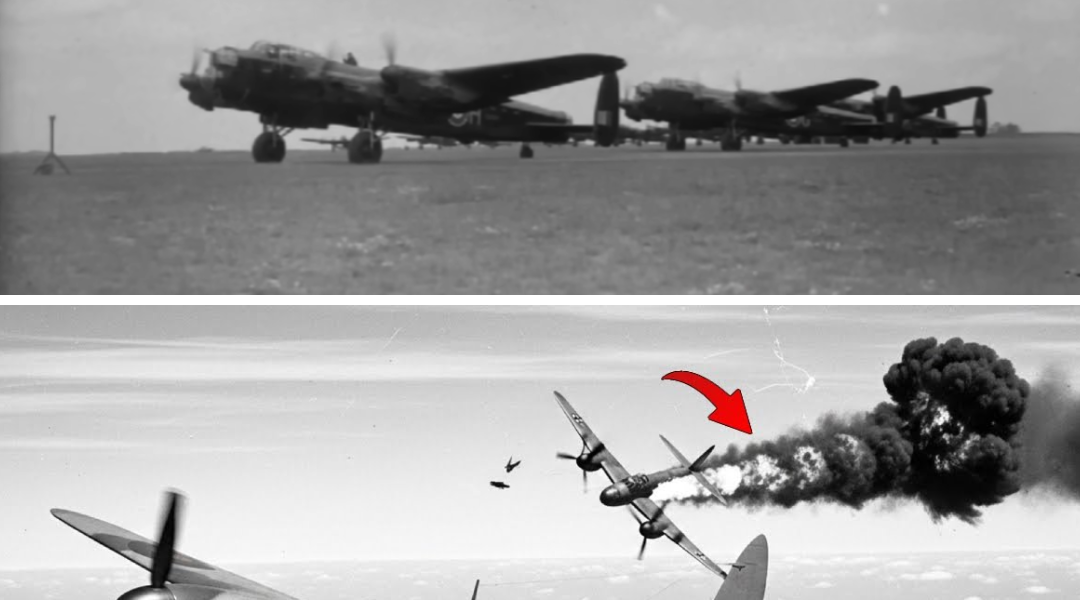

On the darkened runway at RAF Swannington, the wooden shape of a Mosquito shuddered gently as power flowed through its twin Merlin engines. The aircraft looked fragile under the lights—thin wings, smooth fuselage, no heavy armor to speak of—but those who worked the flight line knew better. Tonight, it was one of the deadliest machines in the sky.

At the controls sat Branse Burbridge, just twenty-three years old. Less than two years earlier, he had been a conscientious objector. Now he was a hunter in the dark, leading one of the most dangerous missions of the war.

Beside him, settling into the navigator’s seat, was Bill Skelton. Calm, precise, and brilliant with electronics, Skelton adjusted the unfamiliar-looking equipment mounted beside him—a modified receiver known as Serrate.

This device did not search for aircraft.

It listened.

October 1944 had been a slaughter.

German night fighters had torn into RAF bomber streams with ruthless efficiency. More than two hundred heavy bombers had been lost in a single month. Crews vanished without warning, killed from below by upward-firing cannons before they ever saw their attackers.

The Germans believed the night belonged to them.

They were wrong.

RAF No. 100 Group RAF had been formed for one purpose only: hunt the hunters. Instead of defending bombers, Mosquito crews would slip deep into German airspace, detect enemy radar emissions, and destroy night fighters before they ever reached the bomber stream.

Burbridge and Skelton were among the best.

The Mosquito rolled forward, lifted cleanly into the evening sky, and vanished eastward.

They crossed the English coast low, hugging darkness, then climbed over Belgium. Inside the cockpit, the glow from Skelton’s screens painted his face in soft green light. Signals appeared—faint at first, then stronger.

German radar.

More than one.

“Multiple contacts,” Skelton said quietly.

Burbridge adjusted course without hesitation.

Somewhere ahead, German night fighters were taking off—experienced crews, veterans of dozens of kills, men who believed they were untouchable in the dark.

Tonight, they were broadcasting their position with every radar pulse.

At 19:04, the first contact resolved clearly.

Burbridge eased the Mosquito into position, closing slowly, carefully. No sudden movements. No wasted speed. Ahead, a dark twin-engine silhouette drifted across the sky—a Junkers Ju 88, searching for bombers, unaware of the shadow behind it.

Burbridge believed in one rule above all others.

Stop the machine.

Not the men.

He lined up on the port engine and waited until the distance was certain.

Three seconds.

Four Hispano cannons spoke at once.

Flame erupted from the engine. The Ju 88 rolled violently and fell away, burning. Skelton marked the time without emotion. They did not watch it hit the ground.

There was no time.

Another signal appeared almost immediately.

Then another.

The night was crowded.

Burbridge and Skelton pressed deeper toward Cologne, into the heart of the German night-fighter system. Below them lay Bonn-Hangelar, a major Luftwaffe base. Around it, enemy aircraft orbited in precise patterns, stacked at different altitudes, waiting for orders to intercept the incoming bombers.

Burbridge made a decision few pilots would have considered.

He joined the pattern.

For nearly two minutes, the Mosquito flew with the enemy—same speed, same altitude, invisible among them. German crews saw only darkness. Their radar pointed outward, hunting bombers, not the aircraft flying beside them.

Skelton’s screen filled with contacts.

Seven.

Eight.

A whole nest of hunters.

Burbridge chose one.

The target was a Bf 110, heavier, more dangerous than the Ju 88, favored by veteran crews. Burbridge closed to four hundred feet, close enough to see the glow of exhausts.

He fired.

The port engine detonated in a brilliant flash. The German fighter dropped out of the pattern, spiraling downward in flames.

Only then did the formation realize something was wrong.

The night exploded into confusion.

Warnings crackled across German radio frequencies. Fighters scattered. Ground control shouted orders. The illusion of safety shattered.

One aircraft turned toward the Mosquito.

This one was alert.

The two aircraft rushed toward each other at terrifying speed, tracer fire slicing the darkness. Burbridge held his nerve, waited until the last possible moment, then unleashed everything.

The Ju 88 disintegrated in fire and glass.

Four kills in less than forty minutes.

The Germans broke contact.

Fuel was dropping. Ammunition was low. The mission was complete.

Burbridge turned for home.

Behind them, four German night fighters burned on their own soil—four crews that would never reach the bomber stream, never fire upward into the belly of a Lancaster, never send another crew to their deaths in silence.

As they crossed back over Belgium, Skelton finally exhaled.

They had done more than survive.

They had changed the night.

The results were immediate.

Bomber losses fell sharply. German night-fighter effectiveness dropped. RAF commanders took notice. Tactics were rewritten. Serrate-equipped Mosquitos became the nightmare of the Luftwaffe.

German pilots gave it a name.

“Mosquito Terror.”

Burbridge and Skelton went on to destroy twenty-one enemy aircraft together—the most successful night-fighter partnership in British history. Each kill represented lives saved, families spared telegrams, empty beds that did not need to be mourned.

And yet, they never celebrated.

When the war ended, both men made the same unexpected choice.

They walked away.

Burbridge and Skelton became ministers, dedicating their lives to teaching, reconciliation, and faith. When asked about the war, Burbridge would say only this:

“I aimed for engines, not cockpits. I wanted to stop the machine.”

He never spoke of records.

Never spoke of fear.

But thousands of bomber crews slept in their beds because, on a cold November night, two men chose to fight smarter, not louder.

And in the darkness over Germany, the hunters learned what it felt like to be hunted.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.