German Women POWs Hadn’t Eaten Fruits For 8 Months — When Cowboys Gave Them Apples, They Were Socked. VD

German Women POWs Hadn’t Eaten Fruits For 8 Months — When Cowboys Gave Them Apples, They Were Socked

The Apple That Changed Everything

June 18th, 1944. Camp Hearn, Texas.

The smell reached us before we saw anything. It drifted through the hot, dry air like an invitation, almost apologetic, as though it were unsure it belonged here. It moved past the barbed wire, slipped through the cracks of the wooden barracks, and settled around us in the gravel yard. It was an ordinary smell, but it felt like a betrayal. Meat. Real meat. Not the meager rations we had survived on for the last few years, not the watery soup or boiled turnips, but real beef, fresh, sizzling on a stove somewhere beyond the mess hall doors.

In my years of captivity, I had grown used to the scent of hunger—damp wood, stale air, fear. But this… this was different. This was warm, full, and confident. It had weight. It was something I hadn’t tasted in years. It was the kind of food that reminded you of a life you could barely remember—one where your mother cooked dinner at home, where your kitchen smelled of bread, not bombs. I hadn’t smelled something like this since before the war, and now, standing in the middle of a dusty camp in Texas, I realized that the smell itself was a challenge. It didn’t belong here, in a prison camp.

As we stood in line, I felt my chest tighten. My mind raced through all the things we had been taught. The American soldiers, we had been told, would use food to break us. They would offer it to humiliate us, to soften us, to make us forget who we were, what we were fighting for. So when the smell of meat reached us, I hesitated. This couldn’t be real. Could it? We had learned, for so many months, that food could be a weapon, used to control and break us down. And yet, here it was: warm, real food. It didn’t feel like a trap, but everything I knew said it should.

The line moved forward slowly, and I could feel the weight of the apple in my hand, solid, cool, real. We had not seen fruit for months, and when it had appeared, it was never as something to enjoy. It was a ration, a measure of survival. Fruit wasn’t a treat. It was something that made you anxious, something that reminded you that there was no guarantee of tomorrow. We had learned to eat carefully, rationing everything, even air.

As the line drew nearer to the serving table, I caught sight of the crates of apples. They were just lying there, stacked neatly, no special handling, no fanfare. The apples looked like something from a different world—a world where people ate regularly, where food didn’t disappear, where apples were simply… apples. I wanted to believe that it wasn’t a trap, but it felt impossible. The officer’s voice echoed in my mind, telling us to never accept food too quickly. To never show gratitude. To resist.

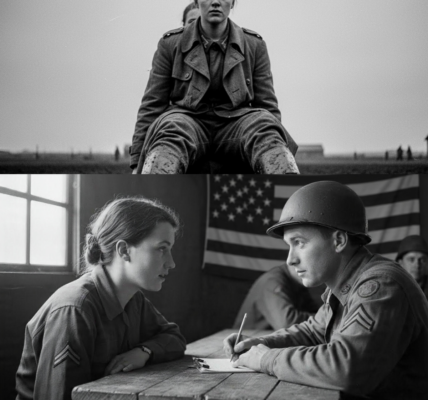

“Don’t touch it,” whispered one of the women beside me, her voice tight with fear. We all stood frozen, watching as the cowboy behind the counter, dressed simply in worn denim and a wide-brimmed hat, ladled beef stew into metal trays. His movements were easy, practiced, as though feeding people was just another part of his day, not something extraordinary.

When it was finally my turn, the cowboy looked at me briefly before dipping the ladle into the pot again. “Step forward,” he said, not unkindly. His voice was calm, unhurried, like he had nothing to prove. The way he moved, with such ease and confidence, unsettled me even more than the food. There was no tension, no drama. It was just food. For prisoners. No questions, no orders, just food.

I took the tray, my hands trembling, and carried it to one of the long wooden tables where the other women were already sitting, unsure of what to do. The stew, thick and steaming, filled my senses. I looked at the spoon, heavy and solid in my hand. The utensils were real. They didn’t bend. They didn’t feel like the tools of a prisoner; they felt like something from a home I hadn’t known in years. Something about this felt wrong—too real, too ordinary.

We all sat down, bowls of food in front of us, staring at the stew as if it were some kind of trap. The apples sat untouched in their crates, the mustard jars were placed casually on the table, and the Americans ate without concern. They didn’t watch us closely. They didn’t look at us with suspicion. It was as though we were just another part of their day.

As I picked up the spoon, something inside me hesitated. Was this a test? I thought. Should we eat? Should we wait? The silence around us was almost unbearable. It was as if we were waiting for the moment when we would be punished, when the food would turn on us, when the cruelty would show its face. But none of that came. The cowboy took another spoonful of his own meal, chewing slowly, without a care in the world.

I felt something inside me crack, just slightly. I had been taught to expect cruelty, to expect humiliation, to expect that generosity was just a mask for something darker. But here, in this room, in this moment, that belief began to erode. The cowboy wasn’t looking for gratitude. He wasn’t watching for our reaction. He was simply eating, simply serving food, as though that was the most natural thing in the world.

And so, I ate. Not quickly, not greedily, but slowly, carefully, with the weight of the moment pressing down on me. The stew was warm, rich with beef, vegetables, and something else I couldn’t quite place. The taste filled me completely, not just in my mouth but in my mind. It was a simple meal, but it held so much more. It held a lesson I wasn’t ready for.

Around me, the other women began to eat too, slowly at first, then with more confidence. Some of them wept as they ate, their faces wet with tears that they didn’t try to hide. We had forgotten how to eat. We had forgotten how to accept something good without wondering when it would be taken away.

But this moment, this simple meal, was different. It wasn’t a trick. It wasn’t a test. It was kindness, offered without expectation, without judgment. It was mercy, offered simply because it was the right thing to do.

When I finished my meal, I looked around the room. The Americans didn’t rush us, didn’t demand anything from us. They just let us eat, as though this was a normal part of their day. And for the first time in years, I felt something shift inside me. Not relief, not gratitude, but a quiet understanding. These soldiers, these Americans, weren’t trying to prove anything. They weren’t trying to make us see how good they were. They were simply treating us like humans—like people who deserved to eat.

That was when I realized the true power of America. It wasn’t in their bombs or their guns. It wasn’t in their factories or their ships. It was in their ability to treat their enemies with dignity, to feed them without expecting anything in return. This was the strength of a nation that had nothing to prove but everything to give.

As we finished the meal, the cowboy came by again, refilling our bowls without asking, without making us feel like we had to thank him. He just did it. And in that moment, I realized that I had been wrong about everything I had been taught. The cruelty I had expected didn’t exist here. The strength of America wasn’t in its ability to dominate; it was in its ability to show restraint, to offer kindness, even to its enemies.

I left that room with a different understanding of the world. I had been fed not just with food, but with a new way of seeing power. It wasn’t the ability to take or control. It was the ability to offer, to give, without expecting anything in return. And that was something I could never forget.

America had shown me that kindness could be stronger than cruelty, and in that lesson, the war I had been fighting inside me had already ended. Not with guns, not with victory parades, but with a meal that offered no judgment, no conditions, just mercy.

And that, I realized, was the real victory.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.