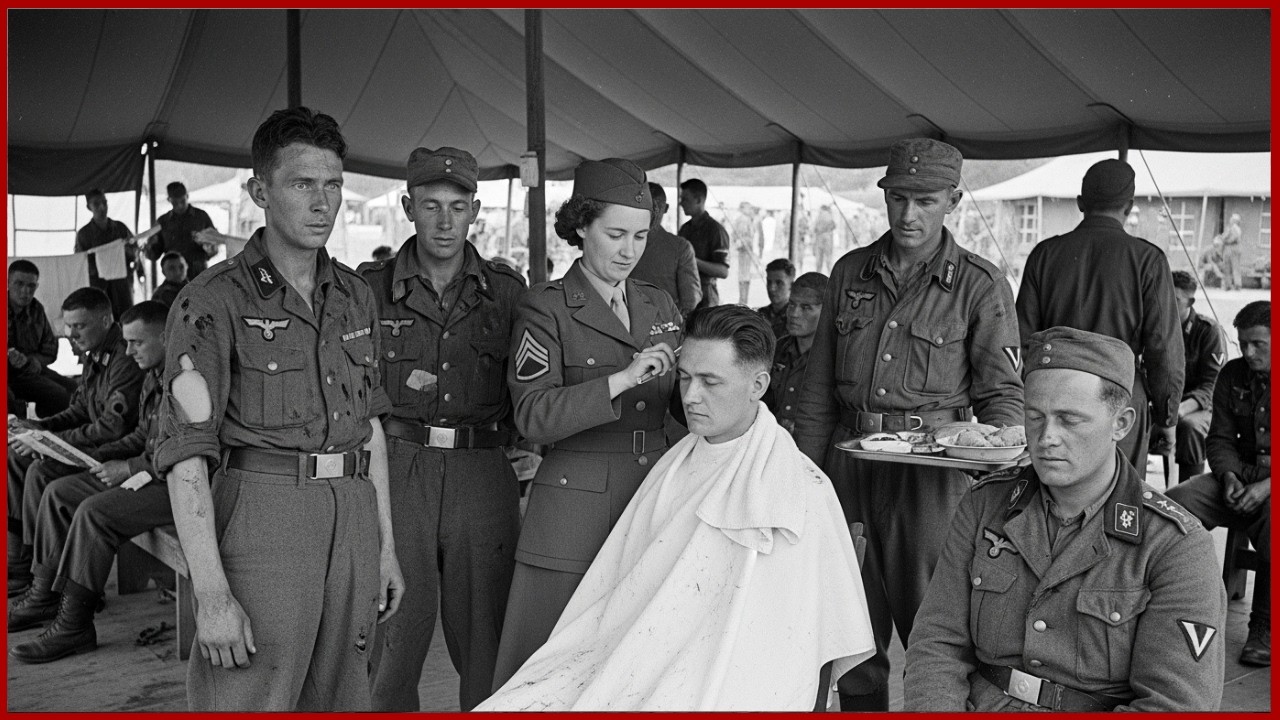

German POWs Were Shocked By Barbers, Tailors, and Laundry in Camps

The Christmas That Changed Everything

December 25th, 1943, was a cold, damp day at Camp Shelby, Mississippi. The American soldiers had no reason to expect that their Christmas celebration would serve a larger purpose than providing a festive meal for the men. But for the 24-year-old German prisoner, Wilhelm Miller, the sight before him was beyond comprehension—it was a revelation that would shatter everything he had been taught.

Wilhelm had been captured just months earlier during the German campaign in Tunisia, part of the Afrika Korps. Now, standing in the doorway of the mess hall, the overwhelming scent of roast turkey, mashed potatoes, cranberry sauce, and freshly baked bread filled the air. It smelled like a meal from another world—a world far removed from the daily suffering he had endured for the past two years.

Before him stretched long tables, laden with food that seemed impossibly abundant. Prisoners like Wilhelm, who had been surviving on turnips and dried bread for months, couldn’t believe their eyes. In the distance, other prisoners played soccer on a manicured field, while others lounged in the shade reading books. This wasn’t the grim, deprivation-filled existence they had expected in American captivity. The German prisoners had been taught that America, despite its vast resources, was struggling—facing shortages, inefficiencies, and collapse. But here, they were presented with a bounty they couldn’t begin to fathom.

“Unmug,” Wilhelm whispered to himself in disbelief, the German word for “impossible.” The American guard standing beside him smiled, understanding the word without translation, and gestured for him to follow the line.

What Wilhelm would witness inside the mess hall, however, would not only surprise him—it would dismantle everything he thought he knew about the war, his enemies, and the world itself.

The Nazi Propaganda Machine

Wilhelm had grown up under the heavy hand of Nazi propaganda. He had been raised in the aftermath of the First World War, and like many Germans, he had witnessed the humiliating terms of the Treaty of Versailles and the ensuing economic collapse. When Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, promising a return to national pride and prosperity, Wilhelm, like many young men, eagerly joined the cause.

Nazi propaganda depicted America as a nation of decadence and decline—a land of gangsters and poverty, of racial conflict and economic ruin. The American people were portrayed as morally corrupt, lazy, and weak, unable to withstand the kind of sacrifice and hardship that Germans were enduring.

Joseph Goebbels, the Reich Minister of Propaganda, carefully cultivated an image of the United States as a place where social and economic chaos reigned. News reports fabricated food riots in American cities, showing images of starving people lining up for bread. These stories were designed to build morale among the German people, painting the Americans as a feeble enemy, incapable of matching Germany’s military might and determination.

But now, standing in the mess hall at Camp Shelby, Wilhelm saw that the reality was far different. The abundance before him—more food than he had seen in years—was a direct contradiction to everything he had been taught.

The Moment of Revelation

As Wilhelm and his fellow prisoners were served the Christmas meal, they marveled at the portions. The turkey, the gravy, the mashed potatoes, the pies—these were luxuries beyond their wildest dreams. In Germany, these kinds of meals were unimaginable for soldiers or civilians, especially during wartime. Most German families had been surviving on the barest of rations, with little more than turnip soup to fill their bellies.

But the food wasn’t the only thing that shocked Wilhelm. What was even more difficult to comprehend was how casually the Americans treated their abundance. After the meal, the guards discarded leftover bread, half-eaten sandwiches, and other food with a lack of concern that left the prisoners in stunned silence. In the midst of a war, where food had become a precious commodity, the American soldiers were discarding what would have been considered a small fortune in Germany.

“I cannot reconcile this with what I’ve been told,” Wilhelm wrote later in a secret letter to his wife that was never sent. “They throw away food like it is nothing. In Germany, we count every crumb. Here, it is thrown away without a second thought.”

Wilhelm’s shock deepened when he saw that the Americans had so much more than just food. After the meal, prisoners were handed packages of items they had not seen in years—cigarettes, soap, toothpaste, even chocolate and candy. The scale of American resources, from food to luxuries, seemed impossible to comprehend.

The most shocking part of this experience was that it wasn’t a special occasion. This wasn’t an elaborate propaganda display for the prisoners’ benefit. This was just an ordinary American Christmas dinner for soldiers—a simple, casual meal that revealed the staggering difference between the material realities of the two nations.

The Reality of American Power

As the months passed, Wilhelm and the other prisoners at Camp Shelby began to see more evidence of the overwhelming power of the United States—not just in terms of military might, but in industrial and agricultural capacity. While German civilians were rationing food and struggling to survive on minimal supplies, the Americans were producing everything they needed in staggering quantities.

Wilhelm’s fellow prisoner, Oberfeld Weeble Hans Winkler, who had been a restaurant owner in Hamburg, was equally stunned by what he witnessed. “The Americans seem to have no concept of scarcity,” he confided to his assistant. “They waste more lumber in a single camp than my father’s construction company would use in a year of civilian projects in Bavaria.”

It wasn’t just the food and the supplies. It was the entire system that the Americans had built—one that operated with such efficiency and abundance that it made everything the Germans had been told about American shortages and weaknesses seem laughable. The American war effort was not just a response to wartime needs; it was an industrial and logistical marvel that operated seamlessly and with seemingly limitless resources.

For the prisoners, the realization that their enemy’s power was not only based on military strength but also on an economic and industrial system that dwarfed their own was a devastating blow. It was a blow to their pride, to their belief in the invincibility of the German war machine, and to their understanding of the very nature of the conflict they had been engaged in.

The Psychological Transformation

By the time Christmas 1944 rolled around, the psychological shift among the prisoners was profound. Many of them had already begun questioning everything they had been taught about the war. The abundance they had witnessed—food, medicine, supplies—had slowly eroded their ideological resistance. The contrast between German scarcity and American abundance was undeniable, and it was reshaping their beliefs about the war, their country, and their place in the world.

At Camp Aliceville in Alabama, Lieutenant Verer Drexler, a young German officer, organized a traditional German Christmas celebration with the tacit approval of American authorities. As the prisoners gathered to celebrate, they could hardly ignore the stark contrast between their pre-war Christmases and the abundance of the American meal. The prisoners sang German carols while eating portions far beyond what any civilian in Germany had seen in years.

One young infantryman, Gunther Rodka, recalled this moment in his post-war memoir. “We sang the songs of home while eating portions that no one in Germany had seen since before the war. Many men broke down during ‘Silent Night,’ not just from homesickness, but from the terrible understanding that was dawning on us all. If the Americans in their prisoner camps could provide this kind of food and comfort so casually, what did that say about the true state of the war?”

The End of the War and the Re-Education

As the war progressed and Germany’s defeat became more apparent, the transformation of these prisoners became even more profound. The exposure to American abundance was not just a physical experience—it was an intellectual one. The prisoners began to understand that the war they had been fighting had been built on false premises.

They had been told that America was a country of weakness, suffering from food shortages and labor unrest. Yet, the reality they saw in American camps was a country brimming with resources—food, technology, and manpower. They had been told that the war would be won through determination and sacrifice, but they now realized that the true key to victory lay in industrial power and efficiency.

As 1945 dawned and Germany faced inevitable defeat, the prisoners began to study American systems. Some, like Wilhelm Miller, took classes in English and technical subjects. Others studied American industrial and agricultural methods. Their eyes had been opened to a new way of thinking—one that emphasized production, efficiency, and a pragmatic approach to problem-solving. This was the American way, and it was a way that had already won the war.

A New Vision for the Future

By the time the prisoners were repatriated in 1946, they carried with them a new understanding of the world—one that was shaped by the simple realities of American abundance. Many of them would go on to contribute to the rebuilding of Germany, using the knowledge they had gained during their captivity to shape the future of their country.

Wilhelm Miller, who had once believed in the superiority of the German system, went on to become a key figure in the German-American business community. He founded a company that facilitated trade between the United States and Germany, using the principles of American industrial efficiency to guide his work.

As the years passed, the lessons of captivity lingered. The Christmas dinners, the casual abundance of food and supplies, the efficient American systems—all of these things had reshaped the worldview of thousands of German soldiers. They had been defeated militarily, but it was the overwhelming material evidence of American superiority that truly defeated their ideology.

In the end, the war was not won just on the battlefield, but through the power of abundance. The American soldier who shared his Christmas dinner with German prisoners had done more than provide a meal—he had shown them a new way of life, one where abundance, not scarcity, was the foundation of strength. This simple act of generosity had the power to reshape nations and transform enemies into allies.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.