German POWs Laughed at Slow U.S. Tractors — Until They Saw Them Feed Entire Cities.NU.

German POWs Laughed at Slow U.S. Tractors — Until They Saw Them Feed Entire Cities

Part 1 — The Laugh at the Fence Line

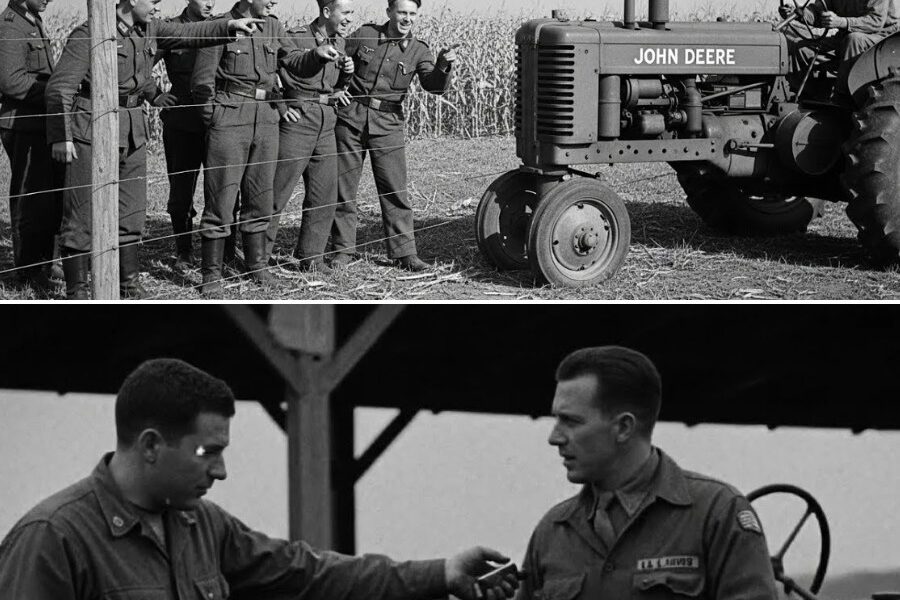

Camp Concordia, Kansas. October 1943.

Two hundred German prisoners of war stood at a fence line watching an American farmer drive past on his tractor.

It was one of those cold, bright Plains mornings where the sky looks scrubbed clean and the wind has teeth. The fields stretched flat and endless, the kind of land that makes a man feel small even when he’s standing upright.

The tractor rumbled along at what looked—at first glance—like a crawl.

One man on the seat.

One machine pulling equipment across acres that seemed to have no end.

The Germans started laughing.

Not loud, not cruel, but the way men laugh when they believe they’re witnessing proof of something they already “know.”

Werner was twenty-four, from a farming village outside Munich. He’d worked his family’s farm before the war—small plots, horses, hand tools, neighbors helping neighbors, a whole village moving like one organism during harvest season.

Now he watched this American farmer—fifty-something, shoulders thick, hat pulled low—sitting alone on a giant John Deere, moving steady and slow across the field.

Werner turned to his friend Klaus and said in German, almost amused:

“This is why they’ll lose the war. Look at this inefficiency. One man, one machine, going so slowly. In Germany we’d have twenty men with scythes and we’d be twice as fast.”

Klaus nodded, the way men nod when the world seems to confirm their assumptions.

“American machinery,” Klaus said. “Big and impressive. No substance.”

Other German prisoners agreed. They’d been taught that American industry was quantity over quality. That Americans relied on machines because they were soft, not because the machines were actually better. That American strength was fake—loud, oversized, shallow.

But what they didn’t understand yet—what they were about to learn in the following weeks—was that they were looking at the wrong measure of speed.

They were measuring motion.

The Americans were measuring coverage.

And that difference was going to crack open everything Werner thought he knew about farming… and about war.

Because in three weeks, Werner was going to understand why one American farmer could feed more people than his entire German village.

And when that understanding hit him, it would not feel like learning.

It would feel like losing something.

Why the Germans Were in Kansas at All

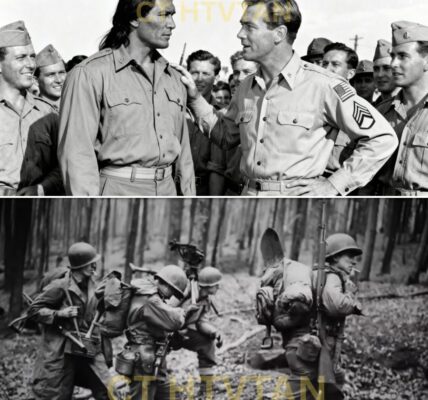

To understand why German prisoners were standing at an American fence line in Kansas, you had to understand how deeply the war had reached into ordinary life.

By 1943, young American men were overseas.

Fighting in North Africa.

In Italy.

On ships crossing oceans.

And farms at home had a problem.

Harvest doesn’t care about geopolitics.

Corn doesn’t wait for victory.

Animals still need feed.

Fields still need to be cut and stored before weather turns.

So the American government did what governments do in total war.

It used every available resource.

That included prisoner labor.

Most of these German POWs had been captured in North Africa. Men who had expected a quick war and found themselves on ships crossing the Atlantic toward detention in a country many had only seen on maps.

Kansas wasn’t “America” to them in any romantic sense.

Kansas was distance.

Space.

A sky so wide it felt unnatural.

And they were assigned to work local farms because there weren’t enough hands left.

It was labor shortage math.

And it created something odd: a place where enemies stood close enough to study each other.

Not through propaganda.

Not through speeches.

Through dirt and machinery.

Werner’s Assumptions

Werner’s farm back home had been twelve acres—maybe a little more, depending on which patches were counted. That was normal. Germany’s countryside was made of small farms stacked close together like quilt squares.

Harvest in Werner’s village wasn’t one man with one machine.

It was dozens of people.

Family members, neighbors, hired help.

Manual work and shared effort.

When harvest came, you didn’t “finish a field” in a morning. You lived inside the harvest. You chased weather. You worked until your hands and back stopped being yours.

The village was the machine.

So when Werner saw one American farmer sitting alone on a tractor, he thought he was seeing weakness.

One man.

Slow.

He assumed it meant the Americans were lazy or inefficient.

He assumed it meant they were compensating for softness with machines that only looked strong.

He didn’t yet understand that the tractor wasn’t replacing a man.

It was replacing a village.

Earl Morrison

The farmer’s name was Earl Morrison.

Mid-fifties.

A man who looked like he’d been carved out of weather and routine.

He wasn’t loud. He wasn’t trying to impress anybody. His tractor didn’t move fast because he didn’t need it to.

He moved like a man who had 500 acres in front of him and wanted to be finished before frost without breaking himself or his equipment.

Earl didn’t see the prisoners as an audience.

He saw them as extra hands assigned by the government.

They’d work.

They’d do what was asked.

That was the arrangement.

But Earl had something else too, something that doesn’t show up in official documents:

Curiosity.

He didn’t know much German. A few phrases picked up from earlier workers and maybe from an older neighbor who’d been raised around German immigrants. But he understood tone. He understood body language. And he understood that these young men were laughing at him.

He didn’t take offense.

Farmers don’t have time for offense.

But he filed the moment away.

Because he knew something these Germans didn’t yet know:

They were about to learn.

“The Work Began”

The Germans were assigned to help with corn harvest.

They expected to do it the way they always had—manual labor, hand tools, everybody moving together.

Instead, Earl showed them the system.

The tractor pulled a mechanical corn picker.

As it moved through the field, the machine stripped ears from stalks, sorted them, and deposited them into a wagon being pulled behind.

One pass.

One machine.

One operator.

Werner watched, still skeptical.

“It’s slow,” he muttered.

Earl heard enough German to catch the tone, and he’d picked up the word “langsam” somewhere along the way. He glanced back, then gestured for the translator—a nearby American guard with German parents who handled communication for farm crews.

Through the translator, Earl explained calmly:

“I’m not trying to win a race. I’m trying to harvest five hundred acres before frost.”

Werner blinked.

He assumed he’d misheard.

“Five hundred?” he said, voice sharp with disbelief.

Earl nodded once, matter-of-fact.

“Speed isn’t the point,” Earl said. “Coverage is.”

Werner felt his brain try to reject the number.

Five hundred acres wasn’t a farm to him.

Five hundred acres was a region.

Back home, his family’s twelve acres took weeks. The whole family. Sometimes hired help. Days that blurred together.

This man was talking about five hundred acres like it was manageable.

Werner shook his head.

“Impossible,” he said.

Earl smiled slightly, not mocking—more like patient.

“Watch,” Earl said.

So Werner watched.

The Machine That Didn’t Get Tired

Day after day, the tractor moved through the fields.

Slow.

Steady.

Methodical.

It didn’t get tired.

It didn’t complain.

It didn’t need rest in the way men needed rest.

It only needed fuel.

And maintenance.

And those things were scheduled, predictable, almost boring.

Werner noticed something strange after the first few days.

In his village, “speed” was bursts.

Men worked hard, then stopped.

Hard, then stop.

Hard, then stop.

The work was fast when hands were fresh and slow when bodies wore down.

The American machine was slow in any single moment.

But it never dropped pace.

It never faded.

It was like a metronome.

And that consistency began to matter in Werner’s head.

By the end of the first week, Earl had harvested more corn than Werner’s entire village produced in a full season.

Werner didn’t say it out loud because saying it out loud felt like admitting something humiliating.

But inside, the laughter died.

By the end of the second week, he stopped joking entirely.

Because the evidence was accumulating too fast to ignore.

The Question That Kept Him Awake

One evening, Werner approached Earl near the barn where tools were stored.

Through the translator, he asked a question that was less about corn and more about comprehension:

“Where does all this go?” Werner asked.

He gestured toward the fields. “Five hundred acres… that is more than our village needs for a year.”

Earl leaned against the tractor like it was just another part of his body.

“This corn?” he said. “Some feeds my cattle. Some gets sold to the elevator. They ship it to cities. Some goes to the military. Some gets sent overseas.”

Werner absorbed that slowly.

One farm feeding cities.

Not just a village.

Cities.

Earl saw his expression and kept going.

“Not just me,” Earl said. “Johnson’s got six hundred acres of wheat. Peterson runs cattle on a thousand acres. Brown’s got soybeans on four hundred. We all feed into the system.”

He paused, then said the line that hit Werner like a weight:

“The system feeds the country. And the country feeds the world.”

That night, Werner couldn’t sleep.

He lay on his thin mattress in the camp barracks doing calculations until his brain hurt.

If American farms were all like this—large, mechanized, connected into infrastructure—the numbers weren’t just “big.”

They were overwhelming.

Germany couldn’t compete.

Not in land.

Not in fuel.

Not in the ability to move food from field to city to port to overseas.

He whispered to Klaus in the dark:

“We were taught American industry was weak,” Werner said. “Cheap goods in quantity, no quality.”

He swallowed.

“But this… this works.”

Klaus was quiet a long time.

Then he said softly:

“My father’s farm is thirty acres. It takes our whole family and hired workers. Earl Morrison manages five hundred acres essentially alone.”

He paused.

“If this is weakness… what does that make us?”

Werner didn’t answer.

Because the answer was too painful.

The Next Questions

The next day, the Germans started asking more questions.

Not mocking questions.

Real questions.

“How much did the tractor cost?”

“How do you maintain it?”

“Where does the fuel come from?”

“How does a man afford this equipment?”

Earl answered patiently through the translator.

Yes, the tractor was expensive.

Yes, he had borrowed for it.

But the productivity meant he could pay the loan and still profit.

Parts were standardized.

Available.

A dealer network existed.

Fuel was abundant by their standards.

And the whole system—banks, infrastructure, rails, grain elevators, government programs—was built to maximize output.

Not because Americans were “better people.”

Because America had designed itself for scale over decades.

Werner watched Earl repair the tractor one afternoon.

The parts were clearly labeled.

Interchangeable.

Designed for replacement without ceremony.

Werner said, through the translator:

“In Germany, only a craftsman can fix this. A specialist.”

Earl nodded.

“That’s the point,” Earl said. “We need systems that work even when things break.”

He paused.

“Even when people aren’t perfect.”

That sentence stuck in Werner’s mind.

Systems that work even when people aren’t perfect.

German engineering prided itself on perfection.

But perfection required expertise at every step.

American engineering assumed imperfection and designed around it.

Different philosophies.

Different outcomes.

And one of those outcomes was standing right there in the field:

A slow tractor that never stopped.

Part 2 — The Day the Numbers Finally Made Sense

By the third week, Werner stopped laughing.

Not because he suddenly became sentimental about American tractors. He didn’t. He still thought the machine looked oversized. He still thought the farmer sitting alone on it looked almost lazy from a distance—one man moving at the pace of an old clock while acres lay ahead of him like an ocean.

But the laughter died because the evidence kept stacking up, day after day, like corn in a wagon.

The tractor didn’t get tired.

It didn’t argue with the weather.

It didn’t slow down because someone’s back was sore or hands were blistered.

It just kept moving.

Slow. Steady. Relentless.

And by the end of the second week, the harvest numbers were no longer something Werner could dismiss as “American show.” He’d watched Earl Morrison harvest more in days than Werner’s entire village produced in a season.

That wasn’t opinion.

That was reality.

And the most unsettling part wasn’t that it was impressive.

It was that it was… normal.

Nobody in Kansas was throwing a parade because Earl could harvest 500 acres.

No one in town treated him like a miracle worker.

It was simply what farmers did here.

Like breathing.

Like rain.

Like work.

Werner carried the new truth around in his chest like a stone.

He didn’t like it.

Because if America could do this—if this was what “ordinary” looked like—then the war wasn’t a contest Germany could win no matter how brave its soldiers were or how perfect its engineering was.

Werner understood that in the way farmers understand weather.

Not through ideology.

Through math.

The Grain Elevator

The day that changed everything didn’t happen in the field.

It happened in town.

It started with something simple: Earl needed to haul a load.

By late October, the weather could turn overnight. Frost didn’t ask permission. So Earl ran his harvest like a man racing a silent enemy.

One morning, after the wagon filled again and again and again, Earl looked at Werner and nodded toward the truck.

“Come on,” he said through the translator. “You’re riding with me.”

Werner hesitated. Prisoners didn’t “ride with” farmers back home. Prisoners worked, then returned to camp. But Earl wasn’t asking like it was optional. It wasn’t a threat either. It was more like… instruction.

Werner climbed into the truck’s passenger seat, stiff-backed, unsure if he was allowed to enjoy the warmth coming through the vents.

The road into town was flat and straight, slicing through fields that looked endless. Werner watched fence lines and windbreak trees pass like slow waves. Everything felt oversized. Not just the equipment. The land itself.

In Germany, villages sat close together, fields patchworked between them. Here, a single farm felt like a province.

They crested a low rise and Werner saw the grain elevator before he understood what it was.

It wasn’t a barn.

It wasn’t a warehouse.

It was a structure that looked like a monument to volume—tall silos, steel legs, conveyors, hoppers, a whole industrial skeleton reaching into the sky.

And lined up along the dirt road leading to it were trucks.

Dozens of them.

Farm trucks, grain trucks, wagons pulled by tractors.

Men stood around talking, drinking coffee from thermos bottles, waiting their turn.

Werner leaned forward slightly, eyes narrowing.

“What is this?” he asked.

Earl didn’t answer right away. He pulled into line like it was just another chore.

“This,” Earl said through the translator, “is where the corn goes.”

Werner watched as the truck ahead of them rolled forward onto a scale. A man in a booth scribbled numbers. Then the truck moved to a chute and dumped its load—thousands of pounds of corn roaring down into a pit like a waterfall made of grain.

Werner’s stomach tightened.

That one truck dumped more corn than Werner’s family could harvest in days.

Then the next truck did the same.

Then the next.

The elevator operator—a man with a cap and a cigarette and the casual confidence of someone surrounded by abundance—walked by and nodded at Earl.

“Busy season,” he said.

Earl nodded back. “Always.”

Werner looked at the operator, then at the silos, then at the line of trucks.

“How much?” Werner asked suddenly, voice sharper than he intended. “How much corn?”

The translator repeated it.

The elevator operator shrugged like it was a normal question.

“This elevator serves maybe forty farms,” he said. “We’ll handle around two million bushels this season.”

The translator spoke the number in German.

Two million.

Werner felt the number hit him like a physical blow.

He did the instinctive farmer thing—he tried to convert it into something his mind could hold.

Bushels to wagons.

Wagons to acres.

Acres to labor.

Labor to time.

His whole region back home—hundreds of small farms—might not produce that much combined.

Werner stared at the silos and suddenly realized why they were built so tall.

Because the ground wasn’t enough.

They needed the sky just to store it.

The elevator operator kept talking, unbothered.

“It goes by rail,” he said, pointing. “Processors, feed lots, cities. Some goes to ports.”

Ports.

Werner pictured maps. Hamburg. Bremen. Ports. Ships.

He looked at Earl Morrison—one man from one farm—and then looked at the convoy of trucks behind him.

The war made sense for the first time in Werner’s life.

Not morally.

Logistically.

This was why America could fight.

Because America could feed.

Not barely feed.

Feed at scale.

And Werner heard himself say the sentence before he could stop it.

“This is why you’re winning,” he said quietly.

The translator hesitated, uncomfortable. But Werner insisted, eyes locked on Earl.

Translate it.

The translator did.

Earl didn’t smile.

He didn’t gloat.

He just looked at Werner with a seriousness that surprised him.

“It’s not about winning,” Earl said. “It’s about systems.”

He gestured toward the elevator again. Toward the trucks. Toward the scale booth. Toward the rail line.

“We built this over decades,” he said. “Roads. Rail. Banks. Dealers. Machines. Storage. Every piece feeds the next.”

He paused, like he was searching for the simplest way to say it.

“Any one piece isn’t that impressive,” Earl said. “But together… together it works.”

Werner sat back in the seat as if the truck had shifted under him.

Together it works.

That was the whole story.

Not the tractor.

Not the picker.

Not the engine.

The system.

The Barracks Meeting

Werner returned to camp that night changed in a way he didn’t fully understand yet.

He wasn’t converted into an American admirer. He wasn’t suddenly happy. He was still a prisoner. Still far from home. Still carrying whatever grief and fear lived in him.

But now he had a new kind of knowledge.

And knowledge is hard to keep quiet when it’s heavy.

After lights out, Werner gathered the other Germans who had been assigned to farms—men from North Africa, mechanics, former farmers, city boys who’d learned field work the hard way.

They huddled near the back of the barracks, careful not to draw attention, but the camp guards weren’t particularly interested in policing German conversations. Kansas nights were cold. Men conserved energy.

Werner spoke in a low voice.

“We need to talk about what we’re seeing,” he said.

Klaus spoke first, the way he always did when Werner left an opening.

“The machines are slow,” Klaus said, “but they never stop.”

He said it like a confession.

“That’s the key,” Klaus continued. “We work fast, but we need rest. The machine works steady and never rests.”

Another prisoner, Heinrich, nodded.

“And the scale,” he added. “The farms are huge. One man has what our entire village would call a region.”

Werner leaned forward, eyes sharp.

“I went to the elevator today,” he said. “Forty farms feed two million bushels into one system.”

The men went quiet.

Someone whistled softly through teeth.

Werner kept going, because he needed to say it out loud.

“One American farmer produces what twenty German farmers produce,” Werner said. “Not because he’s better. Because the system is better.”

He paused, then repeated the phrase Earl had said, because it had burrowed into his mind.

“He said: systems that work even when people aren’t perfect.”

A few men laughed without humor.

“In Germany,” one man said, “we call that sloppy.”

Werner shook his head.

“That’s what I thought,” he said. “But it isn’t sloppy. It’s strategy.”

He looked around at their faces—faces that had once laughed at the tractor from the fence line.

“They design for failure,” Werner said. “They assume things will break, that men will be tired, that crews will be inexperienced. So they build around that.”

He glanced at Klaus.

“They don’t build machines,” Werner said. “They build ecosystems.”

He spoke the word like it tasted strange.

Ecosystems.

Klaus nodded slowly.

“And they have the land,” he said. “And the fuel.”

“And the rails,” someone else added.

“And the spare parts,” Heinrich said. “Everywhere. Any mechanic can fix it.”

The room settled into a silence that felt like mourning.

Not mourning the war.

Mourning the illusion they’d been fed.

Because if America could do this—feed cities, feed armies, feed allies—then the propaganda about American weakness was a lie so big it felt like a crime.

Werner said it quietly, almost to himself.

“We were taught American quantity means cheap,” he said. “But quantity is power when you can feed it.”

No one argued.

Earl’s Patience

The next day, the Germans asked Earl more questions.

Not mocking questions now. Not “why so slow?” questions.

Real questions.

“How much does the tractor cost?”

“How do you get parts?”

“How does one man afford this?”

Earl answered with farmer patience—the kind of patience built from explaining the same things to sons and neighbors for years.

Yes, the tractor was expensive.

Yes, he borrowed.

The bank loan made sense because the productivity paid for it.

Yes, parts were standardized.

Available at the dealer.

Yes, fuel came from American oil fields and distribution networks that reached even rural Kansas.

And yes, the government supported agriculture—programs, price stabilization, infrastructure—because feeding the nation wasn’t optional.

It was national security.

Werner listened, and the more he listened, the more he realized the system wasn’t accidental.

It wasn’t “Americans got lucky.”

It was deliberate design over decades.

They had built roads and rail and credit and supply chains until a man like Earl could sit alone on a tractor and do the work of a village.

The Repair Lesson

One afternoon the tractor needed repair—nothing dramatic, just wear and maintenance. Earl pulled it into the shed, popped open access, and started working.

Werner stood nearby with Klaus, watching.

They expected complexity.

They expected the kind of precision German machines demanded—the kind that required specialist training.

Instead, the parts were straightforward.

Clearly labeled.

Swappable.

Designed to come off without sacred ritual.

Werner couldn’t hold back a comment.

“In Germany,” Werner said through the translator, “each machine… only a craftsman can fix.”

Earl nodded, tightening a bolt.

“That’s the point,” he said. “Beautiful machines that depend on craftsmen fail when craftsmen aren’t there.”

He glanced up at Werner.

“We need systems that work even when people aren’t perfect,” Earl said again.

The sentence felt bigger every time Werner heard it.

Because it didn’t just apply to tractors.

It applied to armies.

It applied to war.

Germany’s war machine depended on experts everywhere.

America assumed the world was messy and built accordingly.

Different mindset.

Different outcome.

The Quiet Exchange

What surprised Werner most was that Earl wasn’t arrogant about it.

Earl didn’t treat the Germans like idiots.

He didn’t mock their farming.

He wasn’t trying to “win” an argument.

He was simply describing how his world worked.

And over time, Earl began asking questions too.

Not about war.

About farming.

German crop rotation methods.

Hand tool techniques for specific tasks.

Small ways German farmers achieved efficiency when land was tight and resources limited.

One day, after watching Werner demonstrate a method for organizing small-scale labor in a tight space, Earl nodded thoughtfully.

“You guys aren’t stupid,” Earl said. “You’re just working with different resources.”

Werner felt something loosen in his chest at that.

Because it meant Earl saw them as competent men, not just enemy labor.

Earl continued, almost conversational.

“You make precise things because you’ve got craftsmen and limited space,” he said. “We make scalable things because we’ve got space and need coverage.”

Different problems.

Different solutions.

Werner nodded, and for the first time since arriving in Kansas, he felt something close to respect that didn’t carry bitterness.

Not respect for America’s “luxury.”

Respect for America’s planning.

For the way they’d built a system that could keep feeding the world even while fighting a war.

The Night That Followed Him

That night, Werner lay awake staring at the barracks ceiling, doing calculations again.

But this time, the calculations weren’t about whether Earl was slow.

They were about whether Germany had ever had a chance.

If one farmer could feed cities… what did that mean for a nation trying to fight that farmer’s nation?

Werner realized something that hurt more than defeat.

Germany hadn’t just been outgunned.

Germany had been outbuilt.

Out-fed.

Out-scaled.

And you can’t win a war if your enemy can keep replacing everything you destroy, keep feeding everyone you can’t, keep moving resources while you ration yours.

Werner whispered into the dark, not to Klaus this time, but to himself:

“We laughed because we thought big meant waste.”

He swallowed.

“Big meant capacity.”

Part 3 — The System That Didn’t Need Them to Believe

By the time winter settled over Kansas, Werner no longer watched the fields like a skeptic.

He watched them like a man who had finally seen the size of the thing he was up against.

The wind came harder now, cold enough to split lips. Frost clung to the edges of the corn stubble. The sky turned that pale, empty blue that makes everything feel exposed. The work slowed, not because Earl Morrison stopped, but because the land itself began shutting down for the season the way land always does.

But even as the pace changed, Werner’s mind didn’t.

Because once you see a system clearly, you can’t unsee it.

And the system didn’t care whether Werner respected it.

It didn’t need him to admire it.

It just kept functioning—quietly, steadily, like it had been doing before he arrived and like it would keep doing long after he left.

The Laugh That Turned Into Silence

The other German prisoners noticed the change in Werner first.

Not because he made speeches.

Because he stopped making jokes.

At the fence line, weeks earlier, he’d laughed at the “inefficiency” of one man on one machine moving slow across endless fields.

Now he didn’t laugh at all.

When a new group of prisoners arrived from another camp detail and made the same joke—“One man? So slow?”—Werner didn’t argue.

He just looked at them for a long moment like they were children repeating something they didn’t understand.

Then he said quietly, in German:

“Watch for a week.”

That was all.

Because Werner had learned that Americans didn’t win by proving points in conversation.

They won by finishing the work.

By the time the week ended, the new men stopped laughing too.

That’s how the lesson spread—not as doctrine, but as evidence.

The Winter Work

With the harvest mostly done, farm work shifted.

Maintenance.

Fence repair.

Hauling feed.

Clearing equipment.

Preparing for next season.

Earl Morrison didn’t slow down because winter came. He adjusted tasks the way farmers do. The tractor wasn’t a symbol to Earl. It was a tool. And tools are only as valuable as what you can keep them doing.

Werner found himself working closer to Earl now—less as an assigned prisoner and more like a regular farm hand.

Not because Earl was “soft” on him.

Because Earl trusted competence.

Werner could fix things.

He could notice what was about to fail.

He could anticipate.

And Earl, being a practical man, valued that.

One afternoon, a belt started wearing unevenly on a piece of equipment. Werner spotted it before it snapped.

He pointed it out through the translator, explaining the misalignment.

Earl adjusted it, nodded, and said something that stuck with Werner for reasons he didn’t expect:

“Good eye.”

That was it.

Two words.

But in Werner’s memory, it landed like something rare.

Recognition without humiliation.

In Germany, praise from above was complicated. It came wrapped in hierarchy and obligation. Here it sounded simple, almost casual.

Good eye.

It made Werner feel, for a moment, less like an enemy and more like what he had been before the war: a farm man who knew machinery.

The Phrase That Became Their Private Scripture

The phrase Earl had said—systems that work even when people aren’t perfect—became the Germans’ quiet mantra.

They repeated it in the barracks, not to flatter Earl, but because it explained everything they were seeing.

Germany’s system assumed perfection.

It demanded experts everywhere.

It punished deviation.

America’s system assumed chaos.

It assumed things would break.

It assumed men would be tired, inexperienced, replaced.

So it built around that.

Werner began noticing how often American life reflected that mindset.

Not just in tractors.

In everything.

The hardware store in town stocked standardized bolts and fittings you could buy without begging.

The dealer network carried parts and manuals.

The grain elevator operated like a machine of its own—scale, storage, distribution.

The roads were maintained enough for heavy trucks.

The rail lines moved product out.

The system didn’t depend on a single genius.

It depended on redundancy.

And redundancy is power in war.

Werner didn’t have language for “systems engineering,” but he understood it like a farmer understands crop rotation:

It isn’t glamorous.

It just works.

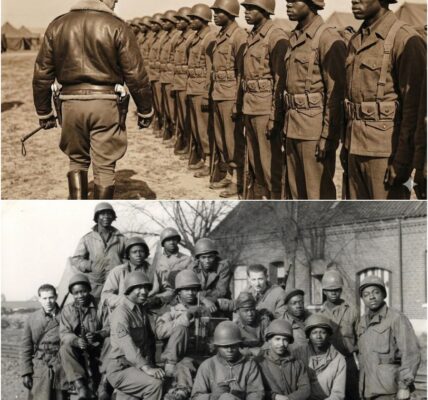

The Most Uncomfortable Truth

The most uncomfortable truth wasn’t that America had big farms.

It was what those farms represented.

If America could feed itself easily, then America could afford to send men overseas without starving at home.

If America could feed itself and still produce surplus, it could feed allies, too.

It meant America wasn’t just fighting Germany with tanks and planes.

America was fighting Germany with calories.

With infrastructure.

With spare parts.

With time.

Werner started to understand why the German propaganda about American weakness had been so desperate.

Because if Germans had understood the real scale of American production, they would have known the war was unwinnable much earlier.

And knowing that would have broken morale.

So the Reich had told stories.

America was soft.

America was decadent.

America made cheap things.

America didn’t have discipline.

Werner now knew the truth was worse:

America didn’t need discipline the way Germany did.

America had capacity.

And capacity is a form of discipline built into infrastructure.

It doesn’t rely on courage.

It relies on planning.

The Night Werner Finally Spoke the Sentence

One night in January, when the wind was rattling the barracks and the stove was barely holding back the cold, Werner sat with Klaus and a few others.

They weren’t talking about home, because home was too painful.

They weren’t talking about the war, because the war was too big.

They were talking about what they had seen—what the work had taught them.

A younger prisoner, barely twenty, asked quietly:

“So what does it mean?”

Werner looked at him.

“It means,” Werner said slowly, “we were fighting a nation that can keep fighting longer than we can.”

The young man frowned.

“But our machines—our tanks—are better.”

Werner nodded once.

“Sometimes,” he said. “In a duel.”

Then he leaned forward, voice low.

“But wars aren’t duels. Wars are production contests.”

No one spoke.

Werner continued, because once you say it, you can’t pull it back.

“You can win a battle and still lose the war,” Werner said. “Because battles cost things.”

“Germany spends craftsmanship,” he said. “We spend time.”

“And America,” Werner said, swallowing hard, “has more time than we do.”

He didn’t mean “time” like clocks.

He meant time as resources.

Time as replacement capacity.

Time as endurance.

He meant: America could absorb loss and keep going.

Germany couldn’t.

Klaus whispered something like a prayer:

“We never had a chance.”

Werner didn’t answer.

Because answering would have required admitting that millions of men had died for a war that was doomed by math.

And that was almost too heavy to carry.

Earl’s Quiet Kindness

Earl Morrison never tried to “convert” the Germans.

He didn’t make speeches.

He didn’t lecture them about democracy.

He didn’t rub victory in their faces.

He just worked.

And in small moments, he treated them like men.

When the temperature dropped dangerously low, he made sure they had gloves and proper clothing for outdoor work.

When one of the Germans—Friedrich—caught a fever and tried to hide it, Earl noticed and sent him back to the barracks.

“Don’t be stubborn,” Earl said through the translator. “Sick men don’t work. They recover.”

That was it.

No moralizing.

Just practical humanity.

Werner noticed those moments more than he noticed big gestures.

Because big gestures can be propaganda.

Small gestures are harder to fake.

The Quiet Shift Inside Werner

By February, Werner’s internal battle wasn’t with Earl or Kansas.

It was with what he had believed before.

He had grown up with a story about German superiority—of engineering excellence, discipline, efficiency.

Those weren’t lies.

But they were incomplete.

Werner now saw that superiority in a single machine doesn’t matter if you can’t replace it.

Discipline doesn’t matter if you can’t feed it.

Efficiency doesn’t matter if your enemy’s scale overwhelms your efficiency.

Werner began to feel something he hadn’t expected:

Respect.

Not the kind of respect that makes you want to join the other side.

The kind of respect that forces you to admit you misunderstood reality.

He respected Earl’s steadiness.

He respected the system Earl was part of.

And he respected the frightening simplicity of it:

It worked without needing genius every day.

It worked without needing perfection.

It worked because it assumed imperfection and built around it.

The War Ends, But the Lesson Doesn’t

When the war ended in Europe in May 1945, the news reached Camp Concordia like a distant echo.

Some prisoners celebrated quietly.

Some mourned.

Some sat still, too empty to react.

Werner felt relief, but it wasn’t clean.

Relief didn’t erase shame.

Relief didn’t erase the knowledge of what Germany had done.

Relief didn’t erase what he had learned.

The camp didn’t empty overnight. Repatriation took time.

Werner kept working on Earl’s farm through summer.

They harvested again.

They repaired equipment again.

They prepared for seasons as if war was just a storm that had passed and left wreckage behind.

When orders finally came for Werner to return to Germany, Earl drove him to the camp gate.

No speeches.

No handshakes that lasted too long.

Earl just nodded at Werner and said something simple through the translator:

“Good luck, son.”

Werner swallowed hard.

He wanted to say something meaningful.

Something that captured what Kansas had done to him.

But he could only manage the truth he had:

“Thank you.”

The Last Thing Werner Took Home

Werner returned to Germany carrying very little.

A bag.

A few clothes.

A head full of thoughts.

He went back to Bavaria and found his village damaged, his family changed, the world smaller and harsher than he remembered.

But he carried one thing that stayed intact:

The lesson of the system.

He told it later to his children, not as admiration for America, but as warning about arrogance.

“We thought they were weak because they used machines,” he told them. “But the machines were only part of it. The real strength was that everything was connected.”

He never forgot Earl Morrison’s phrase:

“Systems that work even when people aren’t perfect.”

Because Werner understood that in war, people are never perfect.

They’re scared.

Hungry.

Young.

Old.

Confused.

Exhausted.

A system built around perfection collapses the moment reality shows up.

A system built around imperfection survives.

And sometimes, that difference is the difference between winning and losing.

Werner had laughed at the tractor.

Then he watched it.

Then he understood.

And by the time he returned home, he no longer laughed at the American way.

He feared it.

Not because it was cruel.

Because it was relentless.

Because it kept coming.

Because it didn’t need him to believe in it.

It just worked.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.