German Generals Laughed At Canadian Logistics, Until Maple Leaf Up Fueled Eisenhower’s Blitz. NU

German Generals Laughed At Canadian Logistics, Until Maple Leaf Up Fueled Eisenhower’s Blitz

August 1944, northern France.

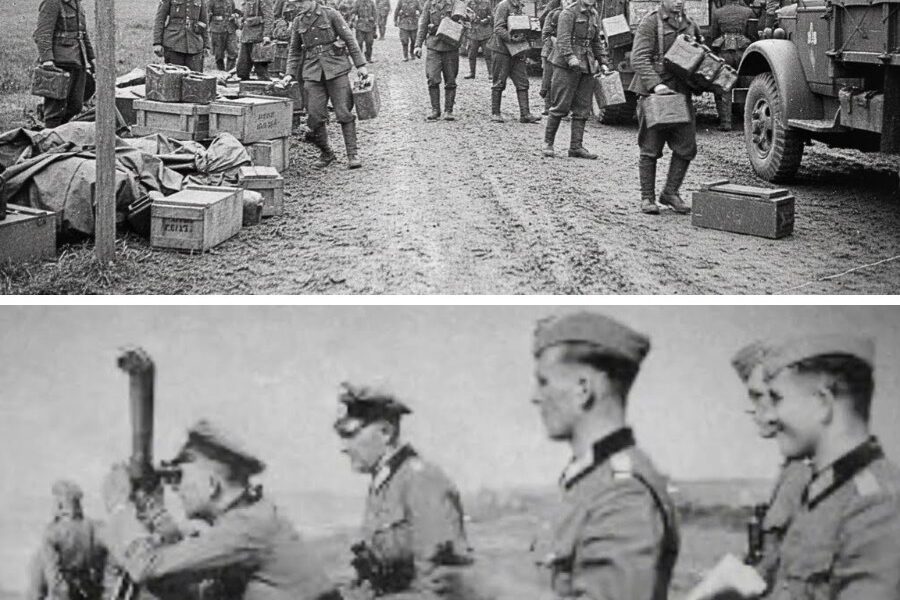

The stone building had once belonged to someone who cared about comfort—thick walls meant to hold warmth in winter and coolness in summer, narrow windows that kept the sun at bay, a heavy wooden door that closed with a satisfying finality. But war had stripped it of all domestic purpose. Now it served as a forward headquarters for German Army Group B, and everything inside smelled like exhaustion: stale cigarette smoke, burnt coffee reheated too many times, damp wool uniforms drying too slowly.

A young intelligence officer—too young, some of the older men liked to mutter, to be standing in front of generals with medals from two wars—spread captured Allied documents across a table that was scarred with knife marks and map pins. His hand shook slightly as he arranged the papers, not from fear of the enemy but from the thrill of bringing good news to men who were desperate for it.

Outside, the summer sun beat down on fields that had been hammered for weeks. Dust hung over roads like a veil. In the distance, the dull thud of artillery came and went like a headache. France was being liberated at a speed that felt unreal, and the German front was being pushed backward in long, bruising strides.

Inside the headquarters, the officer smiled.

He pointed at a map where he had written numbers in neat, confident pencil.

“The enemy advance will stop within days,” he said, and he was careful to sound calm, professional, scientific. Not hopeful. Not desperate. Just certain.

The generals leaned in. Five senior men—hard eyes, stiff collars, the quiet arrogance of professionals who had studied military science like religion. They had been losing battles for months, and yet their belief in mathematics remained intact. Battles could go wrong. Commanders could make mistakes. Luck could shift. But numbers were honest. Numbers did not panic.

The officer tapped the map again.

The Allies, he explained, were racing across France—thirty, forty miles a day. Normandy was behind them now like a bad dream. They were hundreds of miles from the beaches where supplies still came ashore. Every tank, every truck, every soldier drank fuel and ate food and consumed ammunition at a rate that could not be negotiated with. And every mile the Allies advanced stretched the supply line longer.

The officer had done the math carefully and loved the math because it was clean.

“Twenty thousand tons a day,” he said.

Someone whistled softly, and the room filled with the small, grim satisfaction of men hearing a number that sounded impossible. Twenty thousand tons of supplies every day: fuel, shells, spare parts, medical supplies, food. More weight than any sane system could move across shattered France without railroads.

And the railroads—oh, the railroads—were gone.

Allied bombs had wrecked bridges and junctions before D-Day, and now German engineers, retreating, had finished the job with methodical destruction. Twisted tracks. Blown bridges. Marshaling yards turned into blackened skeletons. Whatever had survived the air raids had been sabotaged in retreat. The arteries of France were clogged with ruins.

The ports in Normandy were damaged and limited. The officer had a figure for that too: around seven thousand tons a day, at best, and that was for all supplies, not just fuel. Meanwhile the Allied armies were consuming fuel alone at a staggering rate. The officer had written another number on the map—twelve thousand tons of fuel daily just to keep the advance alive.

He looked up as if waiting for applause.

A general with a chest full of decorations leaned back and laughed, the deep, confident laugh of a man who wanted badly to believe the war had not yet decided to end him.

“The British can barely organize a tea service,” he said, and the others chuckled.

Another general, younger, sharper, waved a dismissive hand as if shooing away a fly.

“The Canadians,” he said with contempt, “colonial amateurs. Farmers from a frozen wilderness. What do they know about modern supply?”

The room erupted again with laughter—the relief of men who had been cornered by events and suddenly saw a door marked hope.

They began making plans with the cheerful ruthlessness of professionals who believed the enemy was about to defeat himself. By mid-September at the latest, they predicted, the Allied armies would grind to a halt somewhere in eastern France. Tanks would sit useless, empty of fuel. Guns would fall silent for lack of shells. Soldiers would slow, hungry and tired, and the advance would become a pause—three weeks, maybe four—just enough time for Germany to build new defensive lines, bring up reinforcements, dig in, reorganize, perhaps even counterattack.

They were not fools. Their calculations were correct.

What they did not understand was that war is not only mathematics.

Sometimes war is a decision—made by exhausted men in a room lit by oil lamps—deciding to behave as if the numbers do not apply to them.

And somewhere behind Eisenhower’s racing armies, on roads lined with dust and desperation, thousands of Canadian truck drivers were about to turn their bodies and machines into an argument against German certainty.

Three months after D-Day, the Allied breakout had gone beyond anyone’s wildest expectations.

German units were retreating in confusion, sometimes in panic, leaving behind wrecked vehicles and abandoned artillery. Towns fell day after day. Some villages were liberated so quickly that French civilians barely had time to pull tricolor flags out of hiding before new columns rolled in. The liberation of France felt like a flood.

But floods have a problem: they carry everything forward… until they run out of water.

The problem that formed behind the Allied triumph was simple, massive, and merciless:

How do you feed an army moving faster than any supply plan was designed to support?

Eisenhower’s forces consumed supplies at a rate that sounded like madness to anyone outside a war room. A single division could eat up roughly eight hundred tons a day: rations, ammunition, fuel, medical supplies, spare parts, everything needed to keep men and machines alive. Multiply that by twenty-five divisions, and you reached that terrible figure—twenty thousand tons every single day.

And each day the armies moved farther from Normandy.

A truck that could make two trips in a day when the front was close now needed days—five days sometimes—to drive forward, unload, and return for another load. Every mile of advance turned into two miles of driving: there and back. The roads clogged. Engines overheated. Dust jammed filters. Trucks broke down like tired animals collapsing mid-stride.

By late August, fuel became the throat the war would choke on.

Forward units were burning through reserves faster than anyone could replace them. Tank crews began siphoning fuel from one vehicle to keep another moving. Some trucks were abandoned by the roadside so their gasoline could be drained into something more valuable. Radios crackled with desperation: Need fuel immediately or we halt.

The leadership faced a brutal truth: there wasn’t enough fuel for everyone. Someone had to get priority.

Patton argued, loudly and endlessly, that his Third Army should receive everything. Give him the fuel, he insisted, and he would reach the Rhine before the Germans could organize a defense. Montgomery demanded priority for his northern push toward Belgium and the Netherlands, arguing his objectives were more important, his route more efficient.

The arguments chewed time like a rat chewing rope.

Meanwhile, the numbers marched toward disaster.

British Second Army reported it had barely enough fuel for a day and a half of operations. Patton’s Third Army was down to less than a day. Some forward units were already halting—ordered not by enemy fire, but by empty tanks.

The Great Advance—this roaring, triumphant liberation—was about to stop.

Not because the Germans had found a miraculous strength.

Because the Allies were about to run out of gas.

That was when Canadian logistics officers stopped pretending the war could be supplied politely.

Canada, before the war, had been a country shaped by distance. It was not something Canadians bragged about; it was something they lived inside, every day. You didn’t move goods across Canada as a hobby. You moved them because survival demanded it. Grain across prairies. Lumber through forests. Supplies into places where winter could kill you if the truck didn’t arrive.

Canadian planners understood something that was easy to miss in Europe: logistics wasn’t an academic field. It was a way of life.

By 1942, the Royal Canadian Army Service Corps had been training thousands of drivers, mechanics, and supply organizers. It wasn’t glamorous. No one dreamed of going to war to drive a truck. Young men wanted to fly or fight or command tanks. But Canadian officers knew the oldest truth in war: brave soldiers with empty rifles become targets; tanks without fuel become metal coffins.

So they trained for the unromantic work.

They developed systems that emphasized flow—constant movement—rather than rigid schedules. They standardized loads, packed supplies in predictable modules, created pre-sorted deliveries so a truck could drop exactly what a unit needed without wasting time searching crates in the dark. They were practical. They were relentless.

In normal weeks, it was solid work—three thousand, maybe four thousand tons moved forward each day. Respectable. Professional. Not headline-worthy.

German intelligence saw those numbers and assumed they would stay the same.

That was the mistake.

Because the Canadian system wasn’t built like a clock.

It was built like a river.

And when the rain came, it could flood its banks.

August 25th, 1944. Paris was free.

It was a moment that looked like pure victory—crowds cheering, bells ringing, the city’s joy spilling into streets like champagne. But three hundred miles west, logistics officers stared at charts with growing horror.

Paris needed food. Two million mouths, starved under occupation, suddenly depended on the Allies. That was not a political talking point. It was tonnage. It was daily deliveries of flour and canned goods and medical supplies. And it was arriving at the worst possible moment: when the supply line was already breaking.

By the end of August, forward units were more than four hundred miles from Normandy.

The French rail system was still a wreck.

Ports were still limited.

Everything had to move by truck.

And there weren’t enough trucks, enough drivers, enough hours.

The math said the offensive should die.

Some staff officers began drafting orders to halt operations within 24 hours. Conserve fuel. Dig in. Wait for rail repairs. Let the Germans regroup.

On August 31st, in a dimly lit command post rumbling with the distant thunder of engines, Brigadier E.W.C. Flavell—director of supply and transport for the army group—spread a new plan across a table.

Around him sat Canadian logistics commanders with faces that looked carved out of fatigue. Men who had been living on coffee and dust. Men who knew what the roads looked like at night, how endless they became, how the mind started to blur in the headlights.

Flavell’s voice was steady.

“We will double deliveries,” he said.

Not next month. Not after new trucks arrived. Not after rest. Not when conditions improved.

“Starting tomorrow.”

The room stared at him as if he’d announced he was going to walk to the moon.

Flavell didn’t blink.

He gave the plan a name simple enough to feel like a promise:

Maple Leaf Up.

Maximum effort.

Every truck. Every driver. Every mechanic.

No polite schedules. No normal rules. No illusion that safety could come first.

If the Allies halted, the Germans would recover. If the Germans recovered, the war could stretch into 1946, maybe beyond. More cities bombed. More soldiers dead. More civilians starving.

So the Canadians would push beyond what everyone said was possible.

Flavell laid out the innovations like a man assembling a weapon:

First: the loop system. Trucks would never return empty. At turnaround points, empty vehicles would be loaded immediately with pre-positioned supplies. No wasted hours. No long waits. Just turn, load, go.

Second: hot swaps. Drivers wouldn’t make full round trips. They’d drive to relay points, jump into fresh loaded trucks, and keep moving. Another driver would take their original vehicle back. Trucks moved constantly, drivers rotated through them like blood through a heart.

Third: rolling depots. Instead of one long haul from coast to front, supply dumps would leapfrog forward every fifty miles. Supplies would move in stages. A broken truck wouldn’t strand fuel hundreds of miles behind the line.

Fourth: priority lanes. Military police would commandeer highways. One-way express routes for loaded supply convoys only. No staff cars. No personal vehicles. Not even generals. If you weren’t hauling supplies forward, you got off the road—or you got arrested.

Fifth: mobile maintenance. Mechanics would travel with convoys, fixing vehicles on the move. Filters swapped in roadside dust storms. Carburetors adjusted without stopping. Engines repaired with hands shaking from exhaustion.

It was reckless. It was dangerous. It was brilliant.

It was the only thing left.

Flavell looked around the table and did not pretend it would be easy.

Men would die in accidents. Bodies would break. Trucks would burn out. Machines would fail the way humans fail—gradually, then suddenly.

But if they didn’t do it, the entire Allied advance would collapse.

And behind every ton of fuel and every crate of shells was a simple truth: without supplies, men at the front would die anyway—just in different ways.

The choice wasn’t between sacrifice and safety.

It was between a sacrifice that could win and a collapse that would drag everyone down.

Captain Harold Morrison—called “Red” because of hair bright enough to look like a signal flare—didn’t sleep more than four hours in three days before Maple Leaf Up began.

He coordinated his truck company from the cab of a moving vehicle, radio crackling, voice hoarse. His map was smeared with dust and sweat. His eyes burned. He would learn later that he barely remembered entire stretches of those days—just a blur of roads, engine noise, commands, and the sensation of time slipping like sand through fingers.

Private Jack Thompson drove for twenty hours straight, dust coating his tongue until it tasted like chalk. His hands cramped on the wheel. The road unrolled in front of him like a punishment. At relay points, he didn’t rest. He swapped into another truck—already loaded, already fueled—and drove again.

Corporal Sarah McLeod, a mechanic, rode standing in the bed of a moving truck, bracing herself against jolts while working with tools that slipped in greasy hands. She replaced a fuel pump while the convoy kept rolling at thirty miles an hour because if she stopped this truck, she stopped the line behind it—twenty trucks, then fifty, then hundreds. A moving convoy was like a living creature: once it stopped, restarting it could take hours, and hours were what they didn’t have.

Drivers slept in fits—four hours a day on average, sometimes less. Not real sleep. Not beds. Just collapsed minutes in the cab while someone else drove, waking with a start, mouth dry, body stiff, then taking the wheel again.

Some men used stimulant pills issued by the army—little chemical sparks to keep eyelids from falling. The pills kept them awake, but they made hearts race and hands tremble. They traded rest for time. They traded long-term health for immediate survival.

The roads at night were worse.

Convoys often drove without headlights to avoid attracting enemy aircraft and to keep the roads from becoming blinding streams of light. Each driver followed the tiny red tail light of the truck ahead, like a chain of fireflies crawling through darkness. If you lost the light, you lost the convoy. If you lost the convoy, you lost the route. If you lost the route, you might end up in a ditch—or in the wrong hands.

The trucks moved like mechanical snakes: endless, disciplined, unstoppable.

French villages became accidental sanctuaries. Café owners opened doors at strange hours. Women handed out coffee and bread to exhausted drivers who barely had time to sip before being waved onward. Children stood by the road offering water. Belgian resistance members guided convoys around blown bridges and craters, saving precious hours.

War was still war—dirty and cruel—but these moments of humanity broke through like small lights in fog.

Not everything was noble.

There were crashes. Trucks rolled over on curves taken too fast by drivers who could barely keep their eyes open. Vehicles caught fire, and men trapped inside died in flames that lit the night sky. Head-on collisions happened on narrow roads where two dark shapes met too late. Mechanics were crushed under vehicles when repairs went wrong. Fingers were lost to machinery. Bones broke. Skin burned.

Forty-seven Canadian drivers died during those two weeks of maximum effort. Three hundred more were injured badly enough for hospitals. Over eight hundred vehicles were destroyed or damaged beyond repair.

The casualty rate, medical officers later said, rivaled combat operations.

And yet the convoys kept moving.

Because if they stopped, the front would go silent. Tanks would become useless. Artillery would ration shells. Infantry would hesitate. The German retreat would become a German defense. And then the war would grind on, chewing lives.

So the trucks kept rolling.

On September 4th, Allied headquarters received supply reports that made staff officers check the numbers twice.

Canadian trucks had moved roughly 15,800 tons forward in three days—more than double their earlier rate.

Fuel reached British Second Army. Enough to resume offensive operations.

Within days, Patton’s Third Army—hours from paralysis—was moving again.

The advance did not stop.

In German headquarters, disbelief spread like sickness.

Intercepts and scout reports showed Allied columns still moving, still fueled, still supplied. The numbers said it shouldn’t happen. And yet it did. The Canadian convoys had rewritten the mathematics by treating them as suggestions.

The German generals who had laughed in August now stared at maps with a different expression—one that professional soldiers hate most: confusion.

In the first half of September, Allied forces advanced an additional hundred and fifty miles beyond what German planners had believed possible. Antwerp was liberated on September 4th, a prize that could eventually solve the supply crisis permanently—if the approaches could be cleared. American First Army stepped onto German soil by September 11th, the first Allied soldiers to do so in years. Canadian First Army pushed toward the Scheldt estuary, beginning the hard work of opening that port.

Behind all of it, truck convoys continued to roll, day and night, hauling the war forward one load at a time.

At German Army Group B, Blumentritt—chief of staff—admitted in a report that they had calculated everything except the possibility that the Allies would simply ignore normal logistics limitations.

That was the part the German mind struggled with. German planning was built on respect for limits: vehicle maintenance cycles, rest requirements, fuel consumption ratios, predictable capacity. The Canadians had taken those rules and burned them in a barrel.

Model, commanding German forces in the west, ordered intelligence estimates revised upward. He told his staff they could no longer count on Allied supply problems to save them. From now on, they had to assume the Allies could supply any operation they attempted.

It was a devastating conclusion.

It meant every German plan that depended on Allied exhaustion was worthless.

It meant the enemy would keep coming.

German soldiers in retreat felt the psychological effect directly. They had been taught the Allies were disorganized. Now they watched endless convoys, saw supplies that never seemed to end, faced an army that refused to slow down.

One captured German sergeant later said the worst part wasn’t Allied firepower—it was the certainty that the Allies would not stop. They had enough fuel, enough shells, enough food to keep moving forever.

Certainty can break morale faster than bullets.

On the Allied side, confidence surged.

When soldiers at the front believed supplies would arrive, they fought differently. They took more risks. They exploited opportunities instead of hesitating. Tank crews advanced boldly, trusting the fuel trucks behind them. Artillery commanders fired without hoarding shells. Confidence, born from logistics, turned into momentum.

And momentum kills.

Those extra weeks—weeks the Germans expected to gain—never appeared. Without time to build proper defensive lines, German forces lost men and equipment. Over a hundred thousand German troops were captured during that sustained September advance—men who might have escaped if the Allies had stalled. Each capture was one less rifle defending Germany’s borders later. Each capture shortened the war.

The Maple Leaf Up operation didn’t just keep the offensive alive; it changed what the offensive could be. Its methods spread fast. American logistics officers visited Canadian units, asked questions, took notes, went back and reorganized their own operations using similar principles. British supply officers, initially skeptical and horrified by the recklessness, quietly adopted the same tactics when they saw the results.

By October, total Allied delivery capacity rose beyond what German intelligence had believed possible. The supply system evolved—under pressure—into something larger and more flexible.

It was, in its own way, a battlefield victory.

Just fought with steering wheels instead of rifles.

And after the war—like so many unglamorous miracles—it was almost forgotten.

Victory parades celebrated infantrymen and tank commanders. Medals went to men who charged machine-gun nests. There were no ribbons for driving eight thousand miles in forty-five days. No monuments for mechanics who replaced parts on moving trucks in the dark. No stirring movies about exhausted drivers following a dim red tail light for twenty hours straight.

The truck drivers returned home quietly. They went back to farms, factories, garages, rail yards. Many rarely spoke about what they had done. When they did, people asked about battles—Did you shoot anyone? Did you see Paris?—not about tonnage.

So the logistics veterans stopped bringing it up. They carried the memory like a private ache: knowing what they had saved, even if no one wanted to hear it.

Yet professionals remembered. Military journals studied it. Doctrine schools dissected it. The people who truly understood war understood the oldest truth: battles are won by fighters; wars are won by the systems that keep fighters fed and armed and moving.

Slow recognition arrived decades later, like a letter delivered too late for the people who needed it most.

In the 1980s and 1990s, museum exhibits began telling the story. Veterans—old now—walked past photographs of convoys and hand-written logs of daily tonnage. Some cried. Others just stood still, seeing young faces again—friends lost in accidents, burned in trucks, broken by exhaustion.

Memorial markers appeared along modern highways in France and Belgium—small signs with a maple leaf, explaining that this quiet roadside had once been a relay point in an operation that kept the Allies moving when the war nearly stalled.

In Antwerp, a monument appeared: bronze hands gripping a steering wheel. The inscription honored Canadian drivers who made liberation possible.

It was late recognition. But it was something.

And the influence lasted beyond monuments.

Modern military logistics—NATO doctrine, convoy planning, continuous operations, priority routes, mobile maintenance—carries echoes of what those Canadians improvised in September 1944. Even decades later, planners in entirely different wars studied the principles: flexibility, surge capacity, relay systems, the ability to expand under emergency without waiting for ideal conditions.

Because sometimes the deciding factor in war isn’t a genius general or a perfect weapon.

Sometimes it’s a tired driver gripping a wheel at 2 a.m., eyes burning, engine making a sound that suggests failure, following a tiny red tail light ahead—because fifty miles forward, a tank crew is down to its last gallon.

That driver doesn’t feel heroic. He feels exhausted. He feels numb.

But he keeps driving.

And because thousands of drivers kept doing that—because mechanics kept fixing engines even when their hands shook—an advance that should have died kept moving, and a war that might have dragged on was shortened, and countless lives that might have been lost were spared.

The German generals in that stone building in August 1944 had not miscalculated the tonnage.

They had miscalculated people.

They assumed “colonials” could not out-organize them. They assumed truck drivers could not defeat equations. They assumed rules would be followed because rules were what professionals respected.

They did not understand that desperation can turn discipline into something fiercer than doctrine: refusal.

Refusal to stop.

Refusal to fail.

Refusal to let the war stall because the numbers said it should.

And that is why—when historians look past the glamour of battle and into the machinery of victory—they find it again and again: the war won not only by guns and generals, but by drivers and mechanics and quartermasters doing work no one applauded at the time.

Work that didn’t look like heroism.

Work that looked like a convoy rolling through the night.

And a simple decision, repeated thousands of times:

Keep going.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.