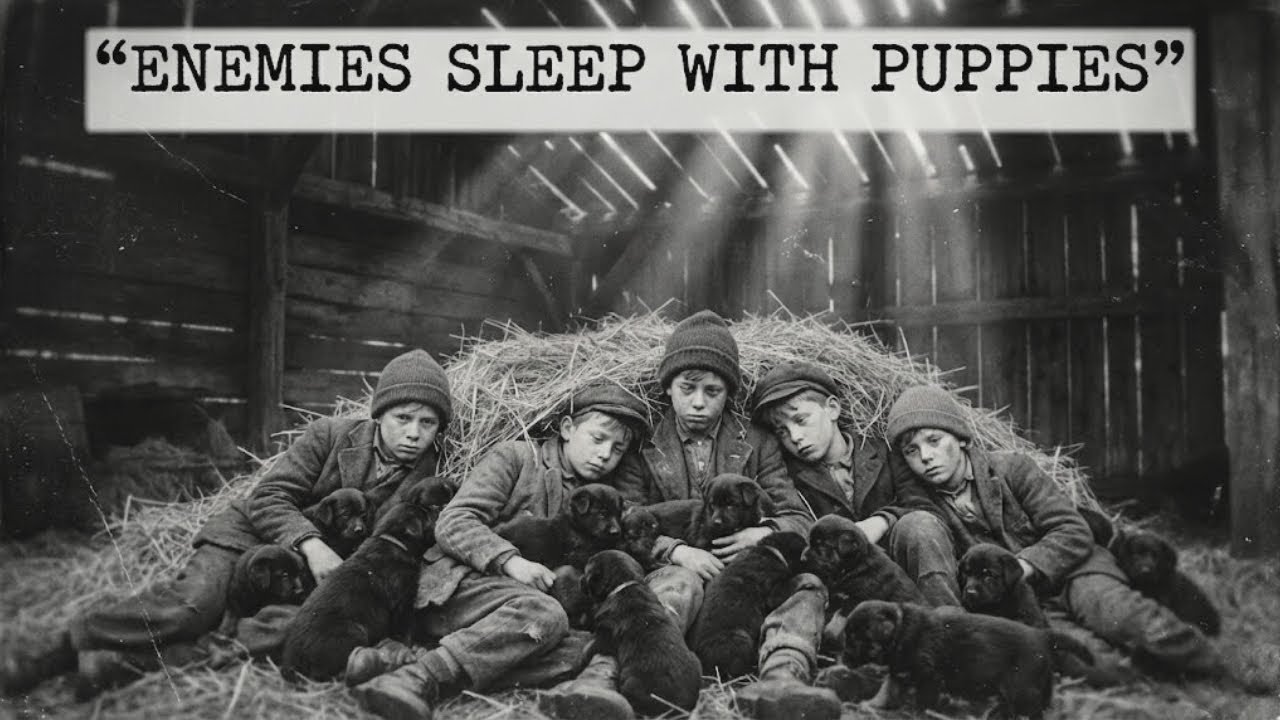

German Child Soldiers Hid in the Barns in America — Not to Escape, But to Sleep with the Puppies. NU

German Child Soldiers Hid in the Barns in America — Not to Escape, But to Sleep with the Puppies

February 14th, 1945. 3 miles east of Fort McCoy, Wisconsin. The temperature hovers just below freezing. A dairy farmer named Harold Jensen stands at the door of his hay barn, flashlight trembling in his hand. Behind him, two armed guards clutch their rifles. Inside, three German boys huddle in the corner, wrapped around a golden retriever and her newborn puppies.

The guards step forward, boots crunching on scattered hay. One boy looks up, tears streaking his dirt smudged face. He’s no older than 16. His uniform hangs loose on his frame. The dog’s tail wags slowly, protectively, as if she’s claiming these boys as her own. Harold Jensen lowers his flashlight. In that instant, he understands something the history books would take decades to acknowledge.

These weren’t hardened soldiers. They were children. And they hadn’t run to escape. They’d run to feel safe. To understand how three German boys ended up sleeping with puppies in rural Wisconsin, you have to go back 2 years. By 1943, the Third Reich was bleeding soldiers faster than it could replace them.

The Eastern Front devoured entire divisions. North Africa collapsed. Italy surrendered. Germany needed bodies. So Hitler turned to the only resource left, children. The Hitler Yugand or Hitler Youth had been indoctrinating boys since 1933. By 1943, it became a feeder system for the Vermacht. Boys as young as 12 were conscripted.

They were given uniforms, rifles, and two weeks of training. Then they were sent to the front. Some never fired a weapon before they saw combat. Others had never left their villages. These boys weren’t volunteers. They were victims of a collapsing empire. Their fathers were dead or missing. Their mothers were starving in bombed out cities.

The state told them they were soldiers. It told them they were heroes. But deep down they were just scared children pretending to be men. By early 1945, thousands of these child soldiers were captured on the Western Front. American forces didn’t know what to do with them. They weren’t criminals. They weren’t officers.

They were prisoners of war technically, but they were also minors. So, the US Army created makeshift P camps across the Midwest. Wisconsin became home to several. Fort McCoy near Sparta held over a thousand German prisoners by February 1945. Most were adults, career soldiers, Luftvafa pilots, Yubot crew. But mixed among them were the boys, the Hitler Yugan conscripts.

They arrived holloweyed and silent. Some had frostbite. Others had infected wounds. All of them carried the weight of a war they never chose. Harold Jensen had volunteered his farm for a labor program. The US government was short on manpower. Dairy farms needed help. So they assigned PS to work the fields under guard. Jensen was skeptical at first.

He’d lost a nephew at Normandy. But when the first group arrived, he saw they were just boys, thin, exhausted, traumatized. He gave them milk, hot meals, warm beds in the barn loft. The guards watched closely. Rifles always loaded. But Jensen noticed something. The boys didn’t talk much. They didn’t laugh. They worked like machines, silent and efficient.

It was as if they’d forgotten how to be human. Before we dive deeper into this extraordinary moment, take a second to like this video and subscribe to the channel. Drop a comment below telling us where you’re watching from. Whether you’re in Berlin or Boston, this story belongs to all of us. It’s a reminder that even in the darkest chapters of history, humanity finds a way to survive. Then the puppies were born.

Jensen’s golden retriever, Daisy, gave birth to six pups in the corner of the hay barn. The boys noticed immediately. One of them, a 16-year-old named Lucas, asked in broken English if he could see them. Jensen nodded. Lucas knelt in the hay, eyes wide. He reached out slowly, as if afraid the moment would shatter.

Daisy licked his hand. Lucas began to cry. The other boys noticed Lucas’s reaction. Over the next few days, they found excuses to visit the barn. They’d linger after chores, pretending to organize tools. Jensen saw them stealing glances at the puppies. He said nothing. The guards noticed, too, but didn’t intervene. It was harmless.

Watching teenage boys melt over newborn dogs wasn’t a security threat. But on the night of February 14th, three boys went missing during evening headcount. The camp alarm sounded. Guards scrambled. The fear was immediate. Escape attempt. Sabotage. Violence. Prisoners of war were still the enemy, no matter how young they looked.

Fort McCoy had protocols. Rifles were loaded. Search parties fanned out across the surrounding fields. Harold Jensen heard the commotion from his house. He grabbed his coat and flashlight, then joined the search. The guards were tense. One of them muttered that if the boys had run toward town, there’d be hell to pay. Jensen didn’t respond. He had a hunch.

He headed straight for the hay barn. The barn door was a jar. Jensen pushed it open slowly. His flashlight beam swept across the interior. At first, he saw nothing. Then, he heard it. soft breathing, the rustle of hay, a faint whimper. He moved toward the back corner where Daisy’s pen was located. There they were, three boys curled together in a nest of hay.

Daisy lay among them, puppies crawling over their chests and arms. One boy had a puppy tucked under his chin. Another held two against his chest. The third was fast asleep, his hand resting on Daisy’s back. None of them had weapons. None of them had maps or tools. They’d simply come to be with the dogs. Jensen stopped.

Behind him, two guards arrived, rifles raised. They saw the scene and froze. One guard, a corporal from Iowa, lowered his weapon first. He stared for a long moment, then shook his head. “Jesus,” he whispered. “They’re just kids.” Jensen approached slowly. The boys stirred but didn’t run. Lucas looked up, fear flickering in his eyes.

He started to speak, stumbling over English words. “I’m sorry,” he said. “We just we wanted.” “It’s okay,” Jensen said quietly. “You’re not in trouble.” Lucas’s face crumpled. He buried it in Daisy’s fur and sobbed. The other boys followed. They wept openly without shame. Daisy stayed perfectly still, as if she understood the weight of what she was holding.

Jensen turned to the guards. “Let them stay,” he said. “Just for tonight.” The corporal hesitated. Protocol said prisoners couldn’t be left unsupervised. But protocol didn’t account for this. He glanced at his partner, who shrugged. “One night,” the corporal said, “we’ll stand watch outside.” Jensen nodded. He brought blankets from the house.

He set them gently over the boys. None of them spoke. They just held the puppies and closed their eyes. For the first time in months, maybe years, they felt safe. The story of that night spread quietly through Fort McCoy. At first, the camp commander was furious. Prisoners couldn’t just wander off, even if they were kids.

But when he heard the details, his anger softened. He didn’t punish the boys. He didn’t punish Jensen or the guards. Instead, he made a quiet decision. The boys could visit the barn under supervision. Over the next few weeks, something remarkable happened. The boys began to talk. Not about the war, not about Hitler or the Reich.

They talked about home, about their mothers, about the farms they’d grown up on. One boy named Otto, had raised goats in Bavaria. Another, France, had lived in a village near the Black Forest. Lucas had been a baker’s son in Hamburg before the bombs came. They’d been told they were soldiers, told they were fighting for the fatherland.

But here, surrounded by puppies and hay and the warmth of Daisy’s breathing, they remembered they were children. They laughed for the first time. They played. They cried without fear of punishment. Harold Jensen watched it all unfold. He’d hated the Germans when the war started. He’d cursed their names when his nephew died. But these boys weren’t the enemy.

They were victims. Pawns in a war machine that chewed up children and called it patriotism. Daisy became their anchor. She didn’t care about uniforms or accents. She didn’t care about politics or borders. She just wagged her tail and licked their faces. The puppies tumbled over them, clumsy and joyful.

For those boys, it was a lifeline, a reminder that the world still held softness. One evening, Lucas asked Jensen if he could keep one of the puppies. “When the war is over,” he said. “When I go home,” Jensen smiled sadly. “You can’t take a dog across the ocean, son.” Lucas nodded, eyes distant. “I know, but maybe maybe I can remember.

” The other boys made similar requests. They knew it was impossible, but the act of asking, of hoping was enough. It meant they believed there was a future, that the war would end, that they’d survive. By April 1945, the war in Europe was collapsing. Hitler was dead. Berlin had fallen. German forces surrendered on mass.

At Fort McCoy, the news was met with quiet relief. The guards relaxed. The prisoners wept. For some, it was joy. For others, it was grief. Their country was gone. Their families were missing. The future was uncertain. The boys on Jensen’s farm learned the news while feeding the cows. Lucas dropped the bucket he was holding. Milk spilled into the dirt. He didn’t move.

Otto put a hand on his shoulder. Fran stared at the horizon, silent. None of them spoke for a long time. That night, they visited the barn one last time. Daisy greeted them as always, tail wagging. The puppies were bigger now, clumsy and energetic. Lucas sat down and pulled one into his lap. He held it close, eyes closed.

“Thank you,” he whispered. It wasn’t clear if he was talking to the dog or to something larger. Over the following months, the boys were processed for repatriation. Most German PS were sent back to occupied Germany by late 1945 and early 1946. The boys would be sent to displacement camps first, then reunited with surviving family, if any existed.

Lucas asked Jensen if he could write. Jensen gave him an address. Lucas promised he would. Otto and Fron did the same. They shook Jensen’s hand. They thanked him in halting English. Then they climbed onto the trucks and disappeared down the dirt road. Jensen never heard from them again.

It’s easy to romanticize stories like this, to see them as heartwarming anecdotes that prove the goodness of humanity. But the truth is more complicated. Those boys had been robbed of their childhoods. They’d been fed propaganda, handed rifles, and sent to die. The fact that they found comfort in a barn with puppies doesn’t erase what was done to them.

Harold Jensen understood that. He didn’t see himself as a hero. He was just a farmer who let some kids sleep in his barn. But in doing so, he gave them something the war had stolen. A moment of peace, a memory of warmth, a reminder that kindness still existed. Daisy, the golden retriever, lived another 8 years. She had more litters.

Jensen kept one of her puppies and named him Lucas. He never told anyone why. He just thought the name fit. The barn still stands on that Wisconsin farm, though it has been rebuilt twice since then. Its beams replaced and its roof reinforced against winters that no longer feel quite as unforgiving as they once did.

The hoft is cleaner now, swept and orderly, with no trace of the straw that once rustled beneath nervous hands and restless bodies. The smell of animals is fainter. The echoes are different. The hay is gone. The puppies are gone. The boys are gone. Time has carried them all forward, scattering them into memory and soil and silence. But the story remains, pressed into the grain of the wood like a fingerprint that refuses to fade.

It stands as a quiet testament to the idea that even in the coldest winters of history, warmth can be found in the smallest places, in moments so brief they almost disappear as they happen. The guards who stood watch that night never forgot what they saw. Even as the years piled up, and the war receded into black and white photographs and half-remembered anniversaries, they carried it with them into marriages, into factory shifts and classrooms, into the slow routines of ordinary American life.

One of them, the corporal from Iowa, spoke about it decades later, his voice softer than his grandchildren expected when the subject of the war came up. He said it was the moment he stopped seeing the enemy as monsters drawn from posters and speeches. It wasn’t a battle or a surrender that changed him, but a barn and a litter of puppies.

They were just kids, he would say, shaking his head as if still trying to understand it. just kids who wanted to hold something soft. The memory stayed with him long after the faces of generals and politicians had blurred. History, for all its ledgers and archives, does not record what happened to Lucas, Otto, or France after that winter.

There are no documents noting their return, no letters preserved in attics, no photographs tucked into albums. Their names do not appear in heroic narratives or official tallies. They vanished into the chaos of postwar Europe the way millions did, absorbed into displacement camps, ruined cities, and new borders drawn by exhausted men. But somewhere, perhaps one of them survived long enough to build a life that didn’t revolve around a uniform.

Maybe he learned a trade or worked a field or raised children who never knew hunger the way he once had. Maybe on a quiet night he told them about a farm in Wisconsin, about a dog named Daisy, about the night he felt safe enough to sleep without fear. The lesson in this story is not simple, and it resists being wrapped up neatly.

It is not a comforting fable about the inevitable triumph of the human spirit, or a claim that kindness alone can erase atrocity. It is instead a reminder of what war does to children, of how it interrupts lives before they have fully begun and forces young people into shapes they were never meant to take.

It is a reminder that the enemy is often just a label applied from a distance and reinforced until it feels real. Behind the uniforms and slogans are human beings who are scared, broken, and desperate for connection, for something that doesn’t demand violence in return. Lucas once said something to Harold Jensen that stayed with him for the rest of his life.

They were sitting in the barn, the cold seeping through the boards despite the shelter, Daisy’s head resting heavily on Lucas’s knee, as if she had always belonged there. The boy’s voice was quiet, careful, shaped by years of learning when to speak and when to stay silent. “The dog doesn’t care about my uniform,” he said, his fingers buried in warm fur.

“She just wants to be held. It’s the first time in years I felt something warm that wasn’t a gun barrel.” Jensen didn’t respond, not because he didn’t have words, but because none were necessary. The truth of it filled the space between them, heavier than any argument impossible to deny. That moment captures the heart of the story more clearly than any daring escape or dramatic confrontation ever could.

It isn’t really about the puppies, or even about the risk Jensen took in letting the boys stay. It is about the raw, almost painful need for warmth, for safety, for something that doesn’t ask for allegiance or obedience. The boys weren’t looking for forgiveness or redemption. They were looking for rest, for love that was simple, uncomplicated, and freely given.

In a world that had reduced everything to sides and targets, that kind of love was almost revolutionary. In February of 1945, three German boys hid in a barn in Wisconsin, and in doing so, they revealed something essential about the human condition. They did not come to sabotage the farm or gather intelligence.

They didn’t whisper plans of escape or dream of returning to the front. They came to sleep with the puppies, to press their faces into warm bodies and breathe in the scent of life instead of smoke and metal. They came to feel small and safe, to remember, if only for a few hours, what it was like to be children rather than soldiers. Harold Jensen gave them that night and the gift mattered more than he ever fully understood at the time.

He offered them blankets and silence and in doing so he reminded anyone who hears the story that humanity persists even when the world seems determined to crush it. It persists in war when cruelty is normalized. It persists in winter when survival itself feels like a victory. It persists in the darkest nights, in the smallest acts, in a farmer who looks at three enemy soldiers and sees boys instead.

A blanket, a kind word, a dog who doesn’t care about borders or languages. That is what we remember if we choose to remember well. Not the movements of armies or the lines drawn on maps, but the moments when someone lowered a rifle and allowed mercy to take its place. The moments when fear loosened its grip just enough for compassion to slip through.

When three boys were allowed to sleep in the hay, guarded not by threats, but by trust. When kindness won, even if only for one night, and even if the larger war continued to rage on beyond the barn walls, the war did end eventually, the way all wars do, not with clarity, but with exhaustion. The boys went home, or didn’t.

The puppies grew up and scattered, living short, ordinary dog lives filled with sun and snow and affection. The world moved on, but that night in the barn, February 14th, 1945, remains where it has always been, a small light in a vast darkness. It reminds us that even when the world is at its worst, there are still places where warmth survives.

Still hearts capable of choosing mercy. Still creatures who offer love without condition. And maybe that is enough. Maybe it has to be one night, one barn, one moment of peace carved out of chaos. It doesn’t undo the war or balance its losses. It doesn’t pretend that suffering can be erased, but it proves something quieter and more enduring.

That even in war, we can still choose who we want to be. The guards lowered their rifles. The boys slept with the puppies. And for one night, held together by breath and fur and shared silence, the war was very far away.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.