French civilians followed the smell of bread — and found an American church feeding their children. VD

French civilians followed the smell of bread — and found an American church feeding their children.

The Scent of Abundance: A French Village’s Transformation

It was December 12th, 1944, and Marie Dubois stood motionless on the bombed-out streets of St. Low, Normandy. The cold, gray sky reflected the desolation of her surroundings. Yet, through the ruins of the war, something entirely unexpected reached her nostrils. It was the unmistakable, comforting scent of freshly baked bread, something she hadn’t smelled in nearly five years. She looked around, bewildered. The village, still recovering from the brutality of the German occupation, had become a symbol of starvation and deprivation.

As she followed the scent, her mind raced with disbelief. She had long ago reconciled herself to the grim reality of wartime hunger and scarcity, a reality that had stolen childhood joys from her grandson, Pierre. But what she saw next would change her understanding of the world forever.

In the village church, now flying an American flag, a group of American soldiers—men she had once feared—were distributing thick slices of white bread slathered with butter and jam. Dozens of wide-eyed children, including Pierre, eagerly filled their hands with the precious food. For a moment, Marie felt as though she were in a dream. The food, a luxury unimaginable just weeks earlier, seemed too good to be true.

Pierre, his hollow cheeks now filled with food, ran out of the church, clutching a small paper bag that contained even more bread and two chocolate bars. “Grand-mère, they say we can come back tomorrow. They have more!” he exclaimed, his voice full of joy. Marie’s heart swelled as tears welled in her eyes. What Pierre held in his hand—two chocolate bars—would have cost three months’ wages on the black market, if they could even be found at all.

Marie looked around, her weathered hand covering her mouth in astonishment. American soldiers were casually discarding cans of peaches, a shocking act of waste that left the gathered villagers in stunned silence. An elderly man, unable to resist, retrieved one of the discarded cans and drank the sweet syrup as though it were fine champagne. Seeing this, the Americans quickly began distributing unopened cans of fruit to the villagers.

What Marie witnessed that morning would forever alter her understanding of the world and the war that had torn it apart. The American soldiers, who had arrived just weeks earlier, were feeding her grandson more food in a single meal than she had been able to provide in an entire month. The generosity she saw that day was not just an act of kindness; it was a revelation of unimaginable abundance.

The Scarcity of Occupation

For years, Marie, like many others in France, had endured the crushing weight of the German occupation. The war had systematically stripped the country of its resources. By 1943, the average daily caloric intake for French civilians had fallen to an alarming 1,200 calories, less than half of what it had been before the war. Children born during the occupation had never tasted chocolate, and many had never seen white bread. Food rations, when available, were pitiful. The Germans requisitioned 70% of French agricultural production, leaving the local population to survive on what little was left.

The black market flourished, but even basic necessities came at astronomical prices. A single egg might cost a day’s wages, and a kilogram of butter could require an entire month’s salary. For Marie and her fellow villagers, food had become a precious commodity, one that often had to be stretched or replaced with substitutes like sawdust, turnips, or chestnut meal.

The Germans had stripped the land of its resources, and by 1944, the French were living in a state of constant deprivation. What Marie had been led to believe was that the Allies, particularly the Americans, were no better off. German propaganda had painted a bleak picture of America—a nation on the brink of collapse, plagued by poverty and unemployment, incapable of fighting a war. The reality of American strength, however, was about to hit home in ways that would make Marie and the rest of St. Low reconsider everything they had been told.

American Abundance

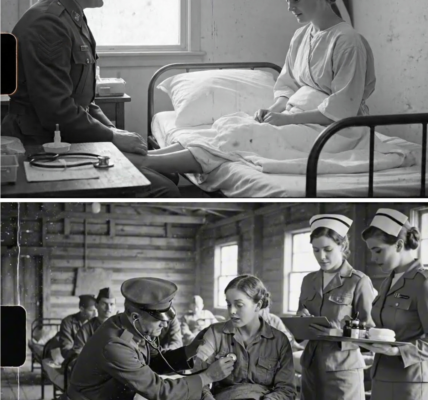

When the American forces landed in Normandy in June 1944, they brought with them not just military power, but an almost incomprehensible abundance. The United States alone produced over 150 billion pounds of food in 1944—nearly twice the combined output of all European countries. The scale of this production was unfathomable to the French civilians who had been starved of the most basic necessities for years. In contrast to the meager rations that the French were used to, American soldiers were provided with daily rations that included canned meats, processed cheese, powdered eggs, chocolate, coffee, sugar, and cigarettes.

Each American division required 70,000 pounds of supplies daily, including 16,000 pounds of food. This staggering logistical feat allowed the Americans to maintain an overwhelming presence on the battlefield while also providing for their soldiers’ needs with an ease that seemed impossible to the war-weary French.

What amazed the French civilians most, however, was not just the quantity of food, but the quality. The American soldiers had access to fresh, nutritious food—something the French could only dream of. Field kitchens operated with equipment that outperformed the finest French restaurants, providing meals that were far more substantial than anything the villagers had eaten in years. For the first time in a long while, the French saw what abundance looked like, and they couldn’t reconcile it with the propaganda they had been fed for so long.

The Generosity of the Occupiers

As more and more villagers began to visit the American camp, the generosity of the American soldiers became apparent. Staff Sergeant Frank Rodriguez, from New Mexico, had taken a particular interest in Pierre, often sharing his rations with the boy and teaching him a few words of English. “The kid reminds me of my little brother,” Rodriguez wrote home to his family. “Except my brother never had to wonder where his next meal was coming from.” Pierre, whose family had subsisted on boiled nettles and dandelion roots during the winter, could scarcely believe the food that was being given to him.

By February 1945, Pierre had gained 7 pounds. His previously gaunt face had filled out, and the persistent cough that had plagued him throughout the occupation began to subside. Marie could see the transformation in him, and it was nothing short of miraculous. The children of St. Low, once too weak to play or laugh, began to regain their strength. Their energy returned, and they began to act like children again—curious, lively, and full of joy.

Marie could hardly believe the change. “He has become a normal boy,” she confided to Dr. Clement, the village physician. “I had forgotten what normal children are like—how much energy they have, how they play and laugh. It’s as if the occupation stole not just our food, but our capacity for joy. And the Americans have returned both.”

A New World

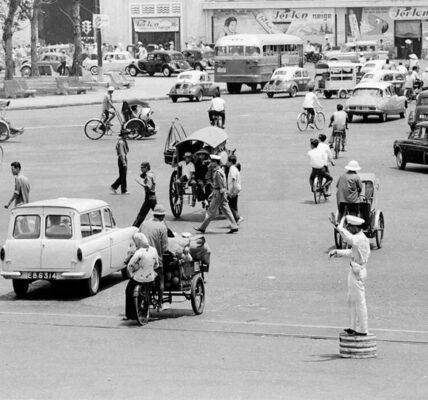

The American abundance extended beyond food. The soldiers brought with them a wealth of technology that had seemed like a distant fantasy to the French. Generators powered field hospitals and command posts, while French villages had been without power for years. American vehicles, including jeeps, trucks, and bulldozers, moved effortlessly through the terrain, while the French had relied on horses and manual labor. A single American combat engineering battalion possessed more mechanical equipment than the entire region of Normandy had before the war.

For Marcel Fornier, a teacher in St. Low and a veteran of World War I, the arrival of the Americans forced a painful reevaluation of everything he had been taught. He had been educated to believe in French cultural superiority, but now he found himself confronted with the reality of American industrial and military power. “I was taught that the Americans were uncultured, materialistic barbarians,” he wrote in his journal. “Now I watch these young men from Tennessee, Oregon, and New York—barely older than my former students—operating machinery beyond anything in our experience. I must ask myself, what other lies have I accepted as truth?”

A Transformation of Mindset

The transformation in St. Low was not just physical but psychological. As the villagers began to experience the abundance that the Americans brought with them, they began to question the ideological narratives they had lived by for so long. The contrast between American plenty and European scarcity was impossible to ignore. The Germans had told them that America was a land of poverty, where people struggled to survive. The reality was that the Americans had an abundance of everything: food, technology, vehicles, and most importantly, generosity.

The American military’s supply operations, which brought vast quantities of food, medical supplies, and equipment to France, were a symbol of a new world order—one in which material abundance was not just a dream, but a tangible reality.

For Marie and the other villagers, this new world would force them to reconsider everything they had been told about their place in the world. How could a country suffering from economic hardship produce such abundance? How could soldiers—who had been portrayed as barbarians—be so generous and kind? These questions became the seeds of a new perspective, one that would shape their understanding of the future and their place in it.

The Legacy of American Generosity

As the months passed, the villagers of St. Low began to rebuild their lives. The material abundance that the Americans had brought with them transformed not just their physical health, but their attitudes and expectations. The children who had once been malnourished and weak grew stronger and healthier. The adults, who had survived years of deprivation, began to question the old ways of thinking about food, work, and wealth.

The psychological impact of American generosity continued to resonate for years. For Pierre, the little boy who had first encountered American abundance through the smell of fresh bread, the transformation was permanent. He grew up in a France that was rebuilding itself with the help of American aid, and in the 1960s, he immigrated to the United States to pursue a career in engineering. He would later return to France, but the lessons he learned as a child in St. Low—lessons about abundance, generosity, and the power of American industrial might—would stay with him for the rest of his life.

Marie, too, saw the transformation in her country. The France she had known before the war, a nation of scarcity and struggle, had been replaced by a nation of hope and possibility. “What I saw that December morning in 1944 was not just food being distributed,” she said, “but a glimpse of what was possible. A world without scarcity, where abundance is commonplace rather than miraculous.”

The Power of Abundance

The story of St. Low and its transformation through American generosity is one that highlights the profound impact of material abundance. The contrast between occupation deprivation and liberation plenty created a space for new ideas to take root. It forced the French people to reevaluate their place in the world, their attitudes toward the future, and their expectations for what could be achieved.

The American soldiers who brought with them not just weapons but food, medicine, and hope were more than just liberators—they were symbols of a new era. Through their generosity, they sowed the seeds of a new world order, one built on prosperity, cooperation, and shared humanity.

The smell of freshly baked bread, the sound of children laughing, and the sight of a community coming together in gratitude are the lasting memories of St. Low’s transformation—a transformation that began with a simple act of kindness and grew into a broader realization of what the world could become when abundance replaced scarcity.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.