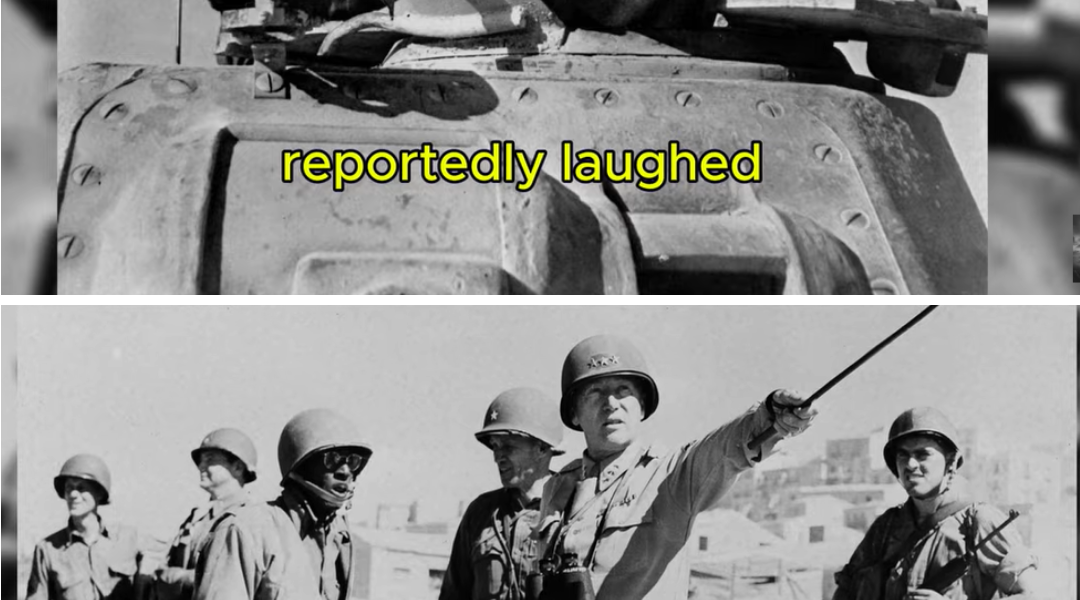

“‘Fire Me?’ — What Patton Said When He Learned Montgomery Wanted Him Removed”

Chapter I – August 1944: The Man Unleashed

In early August 1944, the war in Western Europe changed its rhythm.

For weeks after D-Day, Allied forces had fought inch by inch through the hedgerows of Normandy. Progress was slow, bloody, and exhausting. Many believed this would be the pace of the war until Germany finally collapsed—whenever that might be.

Then George S. Patton was unleashed.

On August 1st, Patton’s U.S. Third Army officially entered combat. What followed shocked not only the German High Command, but the Allies themselves. Instead of grinding forward, Patton’s forces surged. Roads filled with American tanks, trucks, and half-tracks moving day and night. Towns fell not after long sieges, but almost by surprise.

German units disintegrated before they could regroup. Command posts were overrun. Defensive lines collapsed before they were fully drawn on maps.

To the soldiers of the Third Army—mechanics, drivers, tank crews, infantrymen—it felt as though the war had suddenly shifted in their favor. They were no longer reacting. They were hunting.

Many of these men were barely out of their teens. They slept in ditches, ate when they could, and kept moving because stopping meant losing momentum. Their reward was the sight of French civilians cheering from roadsides, waving flags, offering wine, tears in their eyes.

For a moment, it felt like the war might end by Christmas.

Not everyone was pleased.

Across the Allied command structure, one man watched Patton’s advance with growing anger—British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery.

Chapter II – Two Generals, Two Philosophies

Montgomery and Patton had never liked each other.

Their rivalry was not born of personal insult, but of belief. They represented two opposing philosophies of war.

Montgomery believed in careful preparation. He planned meticulously, ensuring overwhelming force before committing troops. Every supply line had to be secured. Every contingency examined. To Montgomery, caution was not weakness—it was responsibility.

Patton believed something very different.

To him, speed was life. Aggression kept the enemy confused and off balance. A good plan, violently executed today, was better than a perfect plan delayed until tomorrow. He believed hesitation killed more soldiers than boldness.

They had first clashed in Sicily in 1943.

Montgomery’s British Eighth Army had been given the primary role. Patton’s American Seventh Army was meant to protect the flank. Patton, furious at being sidelined, turned the campaign into a race.

While Montgomery advanced methodically along the eastern coast, Patton pushed hard through the west, then cut across the island. His troops reached Messina hours before Montgomery’s forces.

The humiliation was public. Newspapers noticed. Soldiers noticed. Even General Eisenhower noticed, though he tried to soften the impact for the sake of Allied unity.

Montgomery never forgot Sicily.

By August 1944, watching Patton’s Third Army tear across France, Montgomery saw history repeating itself—and this time on a much larger scale.

Chapter III – “He Must Be Removed”

Montgomery went to Eisenhower with his concerns.

Patton, he argued, was reckless. His supply lines were dangerously stretched. His coordination with other Allied forces was inadequate. His tactics were undisciplined and risky. If allowed to continue, Montgomery warned, Patton would eventually cause a catastrophe.

The implication was clear.

Patton needed to be removed.

News of the complaint traveled quickly through Allied headquarters. Staff officers talked. Aides overheard conversations. Within days, Patton knew what Montgomery was trying to do.

His first reaction was exactly what one might expect.

He cursed Montgomery privately, calling him jealous and slow. He joked bitterly that the British couldn’t keep up and resented being shown up by Americans.

Then Patton did something unexpected.

He stopped complaining.

Instead of defending himself, pleading his case, or toning down his advance, Patton made a decision that revealed his understanding of both war and human nature.

He would accelerate.

“If Montgomery wants me fired,” he told his staff, “then let’s make him look even slower.”

Patton understood that the argument was not really about safety or doctrine. It was about ego. Montgomery could not tolerate that an American general was proving that aggressive warfare worked.

Patton’s answer was simple: results.

Chapter IV – The Third Army’s Gamble

Patton gathered his commanders.

The message was clear and uncompromising.

Every objective would be taken early. Every advance would go farther than ordered. The enemy would be given no time to recover.

For the soldiers of the Third Army, this meant relentless movement. Tank crews drove until engines overheated. Truck drivers navigated bomb-scarred roads at night without lights. Infantrymen marched, fought, and marched again.

Logistics officers bent rules and ignored regulations to keep fuel and ammunition flowing. Intelligence officers worked around the clock identifying weak points in German defenses.

What appeared reckless was, in truth, calculated aggression.

German commanders depended on time—time to regroup, time to bring up reserves, time to establish defensive lines. Patton denied them that time.

Positions meant to hold for days collapsed in hours. Counterattacks were smashed before they fully formed.

Even Eisenhower took notice.

Reports sent to Washington praised the Third Army’s speed, effectiveness, and fighting spirit. Montgomery’s complaints quietly disappeared from the conversation.

How could one argue for the removal of a commander whose army was liberating France at record speed?

Chapter V – Vindication

By late September, Patton finally encountered the problem Montgomery had predicted.

Supplies ran thin.

The Third Army had moved so far, so fast, that fuel and ammunition struggled to keep up. Eisenhower diverted resources north to support Montgomery’s Operation Market Garden.

Patton was ordered to slow down.

He obeyed—barely.

“Limited operations,” in Patton’s language, meant constant pressure. Probing attacks. Aggressive reconnaissance. Capturing towns “by accident.”

Then Market Garden failed.

British airborne forces were destroyed at Arnhem. The ambitious operation collapsed, achieving none of its major objectives.

The contrast was impossible to ignore.

Montgomery had received priority resources and failed. Patton, operating with restrictions, continued to advance.

When the Battle of the Bulge erupted in December 1944, Eisenhower did not hesitate.

He called Patton.

In seventy-two hours, the Third Army pivoted, moved north, and struck the German flank—one of the most remarkable maneuvers of the war. Once again, American soldiers moved through snow, cold, and exhaustion because their commander demanded the impossible—and believed they could do it.

Patton was never fired.

Montgomery never raised the issue again.

In the end, Patton understood something that went beyond rivalry. Criticism fades. Arguments disappear. Results endure.

The American soldiers of the Third Army proved that courage, speed, and relentless determination could change the course of history. They were not reckless cowboys. They were disciplined, adaptive, and driven by the belief that ending the war sooner would save lives—on both sides.

Patton’s answer to his critics was not words.

It was victory.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.