Female German POWs Thought American Men Were Myths—Then They Saw Cowboys, Lumberjack. NU

Female German POWs Thought American Men Were Myths—Then They Saw Cowboys, Lumberjack

The Cowboys Who Shattered a Myth

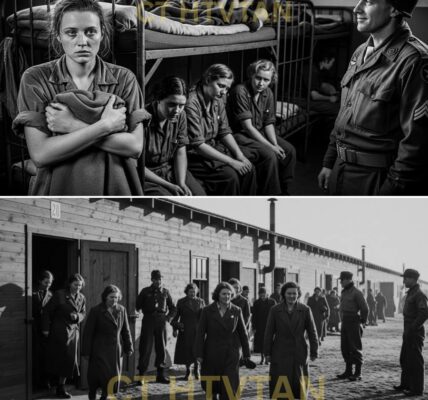

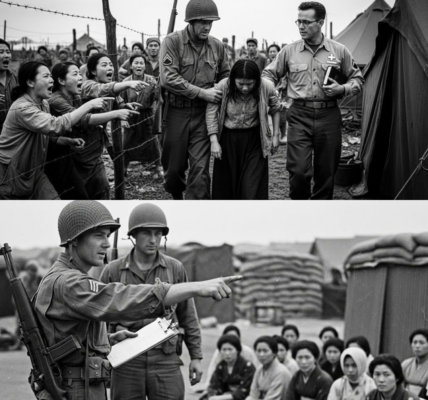

April 7th, 1944, at Camp Trinidad’s mess hall, was a day Helga Schneider would never forget. The 23-year-old former nurse of the Vermach Women’s Auxiliary stood frozen, her heart racing, eyes wide with disbelief. She had spent years of her life, three of them spent in the harshness of war, believing American men were nothing more than propaganda inventions—savage cowboys and brutal lumberjacks used to frighten German soldiers with tales of their strength. But here, standing before her, were 237 American servicemen. Tall, broad-shouldered men, many with weathered faces and calloused hands, who moved with the casual confidence of those who had seen hardship but lived to tell the tale. They looked nothing like the weak, defeated caricatures Helga had been taught to fear.

“I thought they were actors at first,” Helga would later write in a letter smuggled to her sister. “Men hired to intimidate us. But there were too many, hundreds upon hundreds of them. Real cowboys. Lumberjacks with arms thicker than our legs, factory workers who looked better fed than our generals.”

It was the first of many shocks to Helga’s worldview, a worldview built on twelve years of indoctrination. Growing up in Nazi Germany, Helga had been taught to fear the United States. Through films, speeches, and official education, she was convinced that America was a hollow shell—filled with weak, degenerate men who could never match the strength, discipline, and superiority of the German soldier. She had been taught that America’s war effort was nothing more than a myth—a product of racial corruption, a puppet nation controlled by Jewish financiers.

But the reality before her now—those same “brutish” American soldiers—was completely different from anything Helga had imagined.

These soldiers weren’t actors. They were real, hardened men, soldiers and workers who had left their farms and factories to fight a war they believed in. And here they were, treating her and the other women prisoners with a strange kind of respect—a respect that, in itself, began to unravel the very foundation of what she had been taught to believe.

Helga had never seen anything like it. She had expected the savage cruelty she had heard about in German propaganda. She had expected to be treated like an enemy, possibly tortured, and to experience the horrors they said awaited every German soldier who fell into American hands. But instead, they were greeted with professionalism and, surprisingly, care. After months of suffering on meager rations, Helga was shocked to find that American military facilities treated prisoners to more than just basic food. The rations served were nearly double the amount she had received in Germany, with meat, fresh fruit, and even chocolate appearing on their plates daily. In comparison, back in Germany, people were struggling to get by, and soldiers were enduring extreme deprivation.

“I’ve received more meat than I would see in a month in Berlin,” Helga wrote in her journal, still struggling to grasp the magnitude of what was happening. She had thought they were being fattened for some twisted purpose. But when she asked a guard why they were being treated with such “luxury,” the soldier answered with a calm confusion, “This is just normal food, ma’am.” The simplicity of the answer cut through her disbelief.

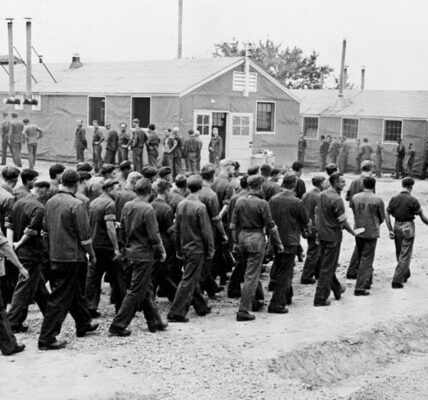

Helga’s disorientation only deepened as she and her fellow prisoners moved to the American Southwest. They had been captured in Tunisia during the final stages of the Africa campaign, where they had served as nurses and support staff for the Africa Corps. Now, in American captivity, they encountered a world that was not only different from what they had been taught—it was its complete opposite. The camp at Camp Trinidad in Colorado, where many of the female German prisoners were housed, was a marvel of comfort and abundance compared to what they had experienced in wartime Germany. Reliable hot water, central heating, plentiful lighting, and, most shockingly, a consistent supply of food that exceeded anything they had ever seen.

It was here, at Camp Trinidad, that Helga had her first encounter with the American cowboys she had been taught to ridicule. The camp employed local ranchers to help with various tasks, men who had left their cattle and horses to serve their country. These cowboys—large, strong, and with an unshakable confidence—represented everything the German propaganda machine had painted as a fantasy.

One such man, a rancher named Carl, invited a group of prisoners to see his ranch. When they arrived, they expected a rustic cabin. What they saw instead was a modern home equipped with running water, an electric refrigerator, and even a radio. The contrast was so stark that it left Helga speechless. “How many years of saving would it take for a German family to afford such luxuries?” she wondered aloud. Carl’s response was simple, “These are common features in most rural American homes.”

As weeks went by, the cognitive dissonance grew unbearable. How could this be? How could these so-called inferior American men live better than the German elites they had been told to revere? The more they saw, the more they realized the magnitude of the deception they had lived under.

The women had been told that America was an oppressive, racially divided society, where a small Jewish elite controlled everything, and the rest of the country was made up of unrefined, weak men. But here they were, watching black, white, and Hispanic men working together on the same farms, managing operations with sophistication and professionalism. It wasn’t just the wealth that shocked them—it was the way it was distributed. It wasn’t just the rich who lived well; it was the working class, the farmers, the cowboys, and the factory workers.

“This is not the America we were taught to expect,” wrote Maria Schmidt, one of the women prisoners, in her journal. “Their wealth isn’t concentrated in the hands of a few; it is spread across society. The cowboys and lumberjacks we were taught to ridicule have land, automobiles, and businesses. They’re free, and they live better than our most respected officials.”

The realization hit like a ton of bricks. The Nazi vision of racial superiority began to unravel with each passing day. These men, who had been mocked as brutish or inferior, were living lives of abundance and dignity that German civilians could only dream of. They treated their female prisoners with a respect they had never known. There was no grand chivalry or exaggerated courtesy, just a simple acknowledgment of their competence and humanity. It was more than Helga could bear. The world she had once believed in—the world where the Germans were the superior race—was coming to pieces before her eyes.

But the disillusionment didn’t stop with just food, housing, and respect. The material superiority of the United States also extended to its industrial might. At Camp Trinidad, the prisoners began to work on local ranches and in factories, where they saw the scope of American production firsthand. One of the most eye-opening experiences came when Freda Müller, another former Vermach nurse, worked in a factory that produced canned goods. “This facility produces more food in one day than my entire home city of Hamburg receives in a month,” she noted in a letter to her family. The scale of American production was beyond their comprehension.

“This is not just about food,” she wrote. “This is about how the Americans can produce more in a day than we can in an entire year. How do they do this? What does it say about our system, about the lies we were told?”

By the end of 1944, as the Allied forces made significant advances and Germany’s defeat became more certain, the prisoners began to understand the full scope of their situation. The vast superiority of the American system wasn’t just about material wealth—it was about a system of production, innovation, and efficiency that left their own country’s war efforts in the dust.

For women like Helga Schneider, the journey from disbelief to acceptance was difficult but transformative. They had been lied to, and now, the harsh truth was impossible to ignore. America’s strength wasn’t just in its ability to fight wars; it was in its ability to create, produce, and sustain an entire nation at a level they could never have imagined.

In her final letter before repatriation, Helga wrote: “We lost this war not because of the might of the American soldier, but because of the might of their economy, of their industry. We fought against a system that was not only more efficient but more generous than ours ever was. This is the America I now know. And it is not a country built on lies, but on truth, abundance, and strength.”

As Helga Schneider and the other women returned to Germany, their understanding of the world had irrevocably changed. They had seen the American cowboys and factory workers for what they truly were—symbols of a nation capable of achieving unimaginable abundance, a nation that had defeated them not just with arms but with the undeniable power of production. They had seen firsthand the material reality that had crushed their ideological beliefs, and they would carry that lesson with them into the post-war years.

For many of these women, the greatest victory the United States had won wasn’t on the battlefield. It was in the minds of those who had been taught to hate and fear it. As Helga Schneider later said in a speech, “When we saw that the cowboys and lumberjacks of our propaganda were real men, living in real abundance, our old world collapsed. In its place grew something new—a recognition that human flourishing comes not from conquest, but from creation, not from domination, but from production. This is the lesson America taught us.”

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.