“Eat This Brown Paste”: When German Women Prisoners Encountered America’s Most Unexpected Wartime Ritual. NU

“Eat This Brown Paste”: When German Women Prisoners Encountered America’s Most Unexpected Wartime Ritual

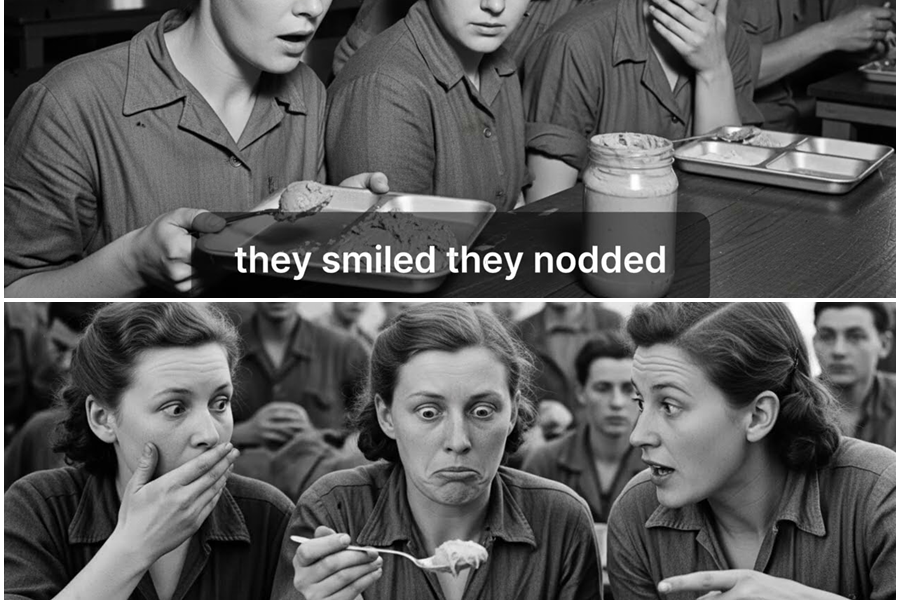

History often remembers wars through battles, generals, and borders redrawn in ink and blood. But some of the most revealing moments of conflict happen far from the front lines—inside kitchens, mess halls, and the quiet routines of daily survival. One such moment, largely absent from textbooks and official summaries, occurred when German women taken into custody near the end of World War II encountered something that left them confused, unsettled, and deeply suspicious.

It was not a weapon.

It was not an interrogation.

It was not even a threat.

It was a spoonful of thick, brown paste.

The Americans called it food.

They ate it every day.

They insisted it was normal.

For the German women prisoners of war who encountered it, nothing about this moment felt normal at all.

An Unexpected Encounter at the War’s End

As Allied forces advanced through Europe in 1944 and 1945, countless civilians, auxiliaries, and support workers found themselves caught in the chaos of collapsing regimes. Among them were German women—some attached to military units, others working in administrative roles, factories, or medical facilities—who were taken into Allied custody during the final months of the war.

Many expected harsh conditions.

Some feared retribution.

Others braced themselves for hunger.

What they did not expect was cultural confusion delivered on a mess tray.

At American-run holding facilities and transit camps, meals followed a strict routine. Rations were measured, standardized, and designed for efficiency rather than comfort. Bread, canned meat, powdered beverages—and always, without exception, a scoop of a dense, brown substance that looked unfamiliar, smelled strange, and defied easy description.

The guards pointed to it casually.

“Eat this.”

“Is It Medicine? Is It Animal Feed?”

For women accustomed to European wartime diets—black bread, thin soups, boiled roots—this new substance raised immediate alarm.

It was not sweet in the way sugar substitutes were sweet.

It was not savory like meat.

It did not resemble jam, paste, or spread known to them.

Some believed it was a nutritional supplement. Others suspected it was feed meant for animals, repurposed due to shortages. A few feared it was experimental, designed to test reactions.

The Americans, meanwhile, showed no concern at all.

They spread it thickly on bread.

They mixed it into meals.

They ate it with visible enthusiasm.

And they did so every single day.

The American Obsession No One Explained

What the German women were witnessing was not improvisation or desperation—it was habit.

For American soldiers, the brown paste was comfort food, energy source, and morale booster rolled into one. It was affordable, shelf-stable, and deeply familiar. Many had grown up with it. Some had eaten it since childhood.

To them, it was as ordinary as bread itself.

But to those seeing it for the first time, especially under the stress of captivity, the ritual was unsettling.

Why did they eat it so often?

How could one food appear at every meal?

Why did they trust it so completely?

No explanation was offered. None was requested.

The expectation was simple: eat what is given.

Food as Power, Routine as Control

In any detention environment, food carries meaning far beyond nutrition. It signals authority, safety, scarcity, and trust. The German women quickly understood that refusing meals was not an option—but acceptance did not equal understanding.

Some forced themselves to eat it, swallowing quickly to avoid tasting too much. Others saved it, traded it, or quietly discarded it when guards were not watching. A few, after days of hunger, began to tolerate it—and eventually, to rely on it.

That transition unsettled them even more.

How could something so strange become necessary so quickly?

Quiet Conversations After Lights Out

At night, whispers spread through bunks and corridors.

“Do you think it changes you?”

“Why do they never run out of it?”

“Why do they smile when they eat it?”

Speculation filled the absence of information. In wartime, uncertainty magnifies every detail. A food item can become a symbol—of dominance, of foreignness, of an enemy whose logic feels impossible to decode.

The Americans never addressed the rumors. To them, there was nothing to address.

A Cultural Gap Wider Than the Ocean

The incident reveals something often overlooked in wartime histories: cultural shock flows both ways, even between victors and captives.

American soldiers arrived with assumptions shaped by abundance, industrial food production, and standardized rations. German women arrived with assumptions shaped by scarcity, tradition, and regional cuisine.

Neither side fully grasped how strange they appeared to the other.

The Americans saw a practical solution.

The prisoners saw a mystery.

Nutrition, Trust, and Survival

Over time, the brown paste proved filling. It sustained energy. It prevented weakness. Whatever fears surrounded it, the body responded with relief.

Some women later admitted that it kept them alive during transport and holding periods when other foods were scarce. Others never overcame their distrust but acknowledged its effectiveness.

Still, effectiveness did not equal comfort.

The memory lingered—not as gratitude, but as bewilderment.

Why This Story Stayed Buried

Official wartime records rarely note such details. Reports focus on numbers, movements, and outcomes—not on the emotional impact of unfamiliar meals.

Memoirs written decades later sometimes mention it in passing, framed as an oddity rather than a defining moment. Yet when survivors spoke privately, the story resurfaced again and again.

Not because it was cruel.

Not because it was violent.

But because it was deeply strange.

The Symbolism of the “Brown Paste”

In retrospect, the incident symbolizes a broader truth about war: victory does not erase misunderstanding.

Even when harm is absent, power imbalances shape perception. A routine for one side becomes a puzzle for the other. Something meant to sustain becomes something feared.

Food, of all things, became a reminder that these women were no longer in a world that followed familiar rules.

After the War, After the Taste

Many of the women returned home carrying memories they struggled to explain. Friends asked about fear, loss, and displacement—not about meals.

Yet years later, some reported that the smell or sight of similar foods triggered vivid recollections of captivity: the mess halls, the guards’ indifference, the quiet tension of forced acceptance.

It was never just about what they ate.

It was about what it represented.

A Forgotten Moment Worth Remembering

This story does not accuse, nor does it glorify. It simply exposes a human moment where two cultures collided under extraordinary circumstances.

The Americans never intended harm.

The German women never expected confusion.

Between them sat a spoonful of brown paste—and a lesson history almost forgot.

War changes everything, including how ordinary things are perceived. Sometimes, the most shocking memories are not of violence, but of how unfamiliar the everyday can become when control, fear, and survival intertwine.

And sometimes, history whispers its loudest truths from the mess hall, not the battlefield.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.